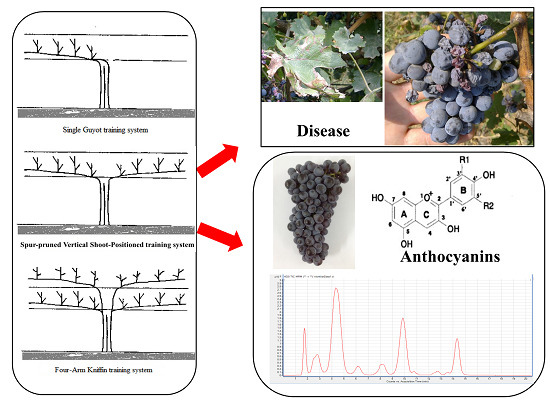

Effect of Three Training Systems on Grapes in a Wet Region of China: Yield, Incidence of Disease and Anthocyanin Compositions of Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Climatic Conditions

2.2. Effect of the Training Systems on the Vine Microclimates

2.3. Effect of the Training Systems on Grape Yield

2.4. Effect of the Training Systems on the Incidence of Grape Disease

| Time | Temperature (°C) | Humidity (%) | Light intensity (×105 lx) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vintage | Date (Month-Day) | DAV | SG | VSP | 4AK | SG | VSP | 4AK | SG | VSP | 4AK |

| 2012 | 8-06 (cloudy) | 11 | 30.1 ± 0.2 b | 30.6 ± 1.5 b | 32.7 ± 0.9 a | 69.5 ± 1.2 b | 69.8 ± 1.9 b | 74.6 ± 3.4 a | 0.152 ± 0.090 a | 0.160 ± 0.015 a | 0.114 ± 0.043 b |

| 8-19 (sunny) | 24 | 32.1 ± 0.9 a | 31.8 ± 0.4 a | 30.6 ± 0.5 b | 51.5 ± 0.8 b | 51.2 ± 1.5 b | 56.5 ± 2.9 a | 0.823 ± 0.054 a | 0.797 ± 0.093 a | 0.526 ± 0.043 b | |

| 9-05 (rainy) | 40 | 25.1 ± 0.4 b | 25.9 ± 0.6 b | 27.8 ± 0.8 a | 88.7 ± 2.9 a | 89.1 ± 2.6 a | 91.5 ± 3.5 a | 0.042 ± 0.007 a | 0.047 ± 0.009 a | 0.031 ± 0.003 b | |

| 2013 | 8-07 (sunny) | 7 | 35.6 ± 1.1 a | 35.9 ± 0.5 a | 33.1 ± 1.0 b | 59.6 ± 0.3 b | 61.1 ± 1.4 b | 64.0 ± 0.9 a | 1.322 ± 0.073 a | 1.414 ± 0.062 a | 0.784 ± 0.089 b |

| 8-15 (rainy) | 15 | 28.6 ± 1.2 b | 28.2 ± 0.4 b | 32.3 ± 0.7 a | 91.2 ± 0.9 b | 90.5 ± 1.9 b | 94.7 ± 2.1 a | 0.034 ± 0.003 a | 0.037 ± 0.004 a | 0.024 ± 0.008 b | |

| 9-06 (cloudy) | 38 | 24.9 ± 0.4 b | 25.3 ± 0.4 b | 27.2 ± 0.8 a | 70.5 ± 1.9 b | 70.6 ± 0.7 b | 74.8 ± 2.1 a | 0.189 ± 0.052 a | 0.168 ± 0.084 b | 0.122 ± 0.099 c | |

| Factors | 2012 | 2013 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG | VSP | 4AK | SG | VSP | 4AK | |

| Germination rate (%) | 85.1 ± 2.8 a | 82.7 ± 3.1 a | 78.5 ± 2.1 b | 80.6 ± 3.9 a | 83.4 ± 4.1 a | 70.5 ± 3.2 b |

| Bearing branches/branch (%) | 81.4 ± 2.1 a | 76.1 ± 1.9 b | 81.6 ± 1.5 a | 95.0 ± 4.8 a | 85.6 ± 2.6 b | 87.9 ± 2.3 b |

| Clusters/vines (n) | 17.9 ± 1.7 c | 20.3 ± 2.0 b | 25.7 ± 2.9 a | 18.3 ± 0.9 b | 18.9 ± 1.7 b | 23.3 ± 2.1 a |

| Fructification coefficient | 1.9 ± 0.2 a | 2.0 ± 0.1 a | 1.4 ± 0.4 b | 1.9 ± 0.2 a | 1.5 ± 0.1 b | 1.4 ± 0.1 b |

| Average per cluster weight (g) | 123.2 ± 6.3 b | 115.1 ± 5.1 b | 141.3 ± 8.9 a | 108.2 ± 3.7 b | 111.7 ± 6.2 b | 141 ± 5.2 a |

| Average yield/vine (kg) | 2.2 ± 0.2 b | 2.3 ± 0.2 b | 3.6 ± 0.4 a | 2.0 ± 0.1 b | 2.1 ± 0.2 b | 3.3 ± 0.5 a |

2.5. Effect of the Training Systems on Berry Maturity at Harvest

| Vintage | Treatment | Sugars (g·L−1) | Total Acids (g·L−1) | S/A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | SG | 207.23 ± 3.7 a | 5.33 ± 0.21 a | 38.98 ± 1.77 a |

| VSP | 192.13 ± 4.1 b | 5.37 ± 0.19 a | 35.90 ± 1.04 b | |

| 4AK | 199.17 ± 3.8 b | 5.70 ± 0.37 a | 35.28 ± 1.19 b | |

| 2013 | SG | 202.83 ± 2.8 a | 5.04 ± 0.18 a | 40.28 ± 0.99 a |

| VSP | 201.99 ± 2.4 a | 5.06 ± 0.22 a | 39.92 ± 1.07 a | |

| 4AK | 204.03 ± 2.7 a | 5.40 ± 0.36 a | 37.81 ± 1.52 a |

2.6. Effect of the Training Systems on the Anthocyanin Composition of the Berry Skins

| Anthocyanins | [M+]/[M − H]+ (Frag. MS2 m/z) | 2012 | 2013 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG | VSP | 4AK | SG | VSP | 4AK | ||

| Dephinidin-3-O-glucoside(A1) | 465 (303) | 1011.8 ± 89.45 a | 533.49 ± 49.32 b | 419.73 ± 33.27 b | 446.28 ± 24.38 b | 518.82 ± 19.35 a | 497.14 ± 21.03 a |

| Cyanidin-3-O- glucoside(A2) | 449 (287) | 268.32 ± 24.67 a | 132.83 ± 11.29 b | 88.62 ± 9.48 c | 110.47 ± 9.77 a | 101.87 ± 7.14 a | 107.82 ± 8.31 a |

| Petunidin-3-O- glucoside(A3) | 479 (317) | 1551.66 ± 160.32 a | 1060.2 ± 100.42 b | 731.31 ± 51.09 c | 864.86 ± 49.12 a | 930.16 ± 34.33 a | 904.14 ± 32.91 a |

| Peonidin-3-O- glucoside(A4) | 463 (301) | 1050.28 ± 83.22 a | 857.19 ± 79.87 b | 576.88 ± 43.44 c | 843.29 ± 46.41 a | 739.98 ± 35.79 b | 762.12 ± 31.11 b |

| Malvidin-3-O-glucoside(A5) | 493 (331) | 6563.04 ± 532.3 a | 5703.17 ± 233.89 a | 3719.25 ± 244.5 b | 5659.64 ± 99.3 b | 5863 ± 100.2 a | 5554.96 ± 93.3 b |

| Delphinidin-3-O-(6-O-acetyl)-glucoside(A6) | 493 (331) | 325.23 ± 22.1 a | 142.66 ± 10.36 b | 133.56 ± 10.22 b | 125.28 ± 8.77 b | 158.88 ± 9.38 a | 164.41 ± 11.31 a |

| Cyanidin-3-O-(6-O-acetyl)-glucoside(A7) | 491 (287) | 94.45 ± 8.22 a | 51.28 ± 4.11 b | 31.73 ± 2.79 c | 35.43 ± 2.54 a | 34.9 ± 3.01 a | 37.49 ± 2.90 a |

| Petunidin-3-O-(6-O-acetyl)-glucoside(A8) | 521 (317) | 985.88 ± 79.49 a | 548.2 ± 49.32 b | 449.4 ± 33.21 b | 473.14 ± 34.77 b | 582.44 ± 57.90 a | 597.41 ± 58.33 a |

| Peonidin-3-O-(6-O-acetyl)-glucoside(A9) | 505 (301) | 640.24 ± 45.77 a | 572.74 ± 42.89 a | 375.78 ± 30.21 b | 568.99 ± 28.86 a | 517.69 ± 19.77 b | 535.19 ± 17.73 b |

| Malvidin-3-O-(6-O-acetyl)-glucoside(A10) | 535 (331) | 7174.56 ± 567.44 a | 6384.86 ± 484.44 a | 3865.15 ± 330.23 b | 6507.66 ± 122.01 b | 7058.84 ± 114.56 a | 6790.81 ± 79.30 b |

| Delphinidin-3-O-(cis-6-O-coumaryl)-glucoside(A11) | 611 (303) | 4.02 ± 0.32 a | 3.58 ± 0.21 a | 2.17 ± 0.19 b | 2.44 ± 0.10 a | 2.14 ± 0.11 b | 2.32 ± 0.09 a |

| Delphinidin-3-O-(trans-6-O-coumaryl)-glucoside(A12) | 611 (303) | 63.18 ± 5.77 a | 47.68 ± 3.92 b | 36.12 ± 2.87 b | 35.14 ± 3.21 a | 36.55 ± 2.28 a | 37.48 ± 3.10 a |

| Cyanidin-3-O-(cis-6-O-coumaryl)-glucoside(A13) | 595 (287) | 2.36 ± 0.19 a | 1.52 ± 0.11 b | 1.5 ± 0.10 a | 1.33 ± 0.07 b | 1.34 ± 0.05 b | |

| Cyanidin-3-O-(trans-6-O-coumaryl)-glucoside(A14) | 595 (287) | 31.72 ± 3.09 a | 36.4 ± 3.21 a | 18.01 ± 1.78 b | 19.6 ± 0.82 a | 17.77 ± 0.60 b | 18.13 ± 0.52 b |

| Petunidin-3-O-(cis-6-O-coumaryl)-glucoside(A15) | 625 (317) | 15.79 ± 1.02 a | 8.82 ± 0.52 b | 11.2 ± 0.77 a | 9.12 ± 0.34 b | 9.7 ± 0.52 b | |

| Petunidin-3-O-(trans-6-O-coumaryl)-glucoside(A16) | 625 (317) | 222.22 ± 17.34 a | 193.94 ± 16.21 a | 133.6 ± 9.88 b | 141.81 ± 8.35 a | 144.83 ± 7.19 a | 142.75 ± 4.02 a |

| Peonidin-3-O-(cis-6-O-coumaryl)-glucoside(A17) | 609 (301) | 23.52 ± 2.01 b | 31.46 ± 2.34 a | 20.07 ± 1.90 b | 25.44 ± 1.92 a | 21.08 ± 2.02 b | 21.64 ± 1.27 b |

| Peonidin-3-O-(trans-6-O-coumaryl)-glucoside(A18) | 609 (301) | 290.73 ± 20.11 a | 309.58 ± 23.41 a | 211.76 ± 18.78 b | 276.59 ± 18.34 a | 227.41 ± 14.30 b | 243.18 ± 10.20 b |

| Malvidin-3-O-(cis-6-O-coumaryl)-glucoside(A19) | 639 (331) | 137.15 ± 14.22 b | 236.79 ± 24.90 a | 104.89 ± 9.11 c | 192.65 ± 16.30 a | 155.37 ± 12.39 b | 143.23 ± 12.90 b |

| Malvidin-3-O-(trans-6-O-coumaryl)-glucoside(A20) | 639 (331) | 1916.42 ± 156.66 a | 2055.69 ± 178.44 a | 1245.98 ± 104.89 b | 1900.48 ± 97.23 a | 1723.18 ± 76.34 b | 1639.2 ± 55.45 b |

| Total concentration | 22,380.3 ± 2017.82 a | 18,901.74 ± 1591.05 a | 12,165.53 ± 979.72 b | 18,230.69 ± 244.34 b | 18,778.45 ± 267.73 a | 18,200.76 ± 200.41 b | |

2.7. Effect of Three Training Systems on the Modified Anthocyanins

2.8. PLS-DA Analysis of the Concentrations of Individual Anthocyanin in Two Vintages

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Experimental Field Site

3.2. Experimental Design and Berry Sampling

3.3. Meteorological Survey

3.4. Grape Yield

3.5. Incidence of Grape Disease

| Grade | Leaf Disease Spot Area (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0.1–2.5 |

| 2 | 2.6–5.0 |

| 3 | 5.1–15.0 |

| 4 | 15.1–30.0 |

| 5 | 30.1–50.0 |

| 6 | 50.1–70.0 |

| 7 | 70.1–85.0 |

| 8 | 85.1–95.0 |

| 9 | 95.1–97.5 |

| 10 | 97.6–100 |

| Grade | Infected Berries per Cluster (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | <5 |

| 2 | 5.1–15.0 |

| 3 | 15.1–30.0 |

| 4 | 30.1–45.0 |

| 5 | 45.1–65.0 |

| 6 | 65.1–85.0 |

| 7 | >85 |

3.6. Reducing Sugar and Titratable Acidity

3.7. Anthocyanin Compositions

3.8. HPLC-DAD/ESI-MS Analysis of Anthocyanin Compounds

3.9. Chemicals and Standards

3.10. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Teixeira, A.; Eiras-Dias, J.; Castellarin, S.D.; Gerós, H. Berry phenolics of grapevine under challenging environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 18711–18739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.F.; Ning, P.F.; Xu, T.F.; Zhang, Z.W. Effect of rain-shelter cultivation of Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet gernischet on the phenolic profile of berry skins and the incidence of grape diseases. Molecules 2012, 18, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladstone, E.; Dokoozlian, N.K. Influence of leaf area density and trellis/training system on the light microclimate within grapevine canopies. Vitis 2003, 42, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, A.G.; Heuvel, J.E.V. Influence of grapevine training systems on vine growth and fruit composition: A review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2009, 60, 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, T.K.; Dry, P.R.; Iland, P.G.; Botting, D.; Dick, J.; Kennedy, U.; Ristic, R. Response of Shiraz grapevines to five different training systems in the Barossa Valley, Australia. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2003, 9, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, P.; Poni, S.; Rotundo, A. Ecophysiology and vine performance of cv.“Aglianico” under various training systems. Sci. Hortic. 2001, 87, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koes, R.; Verweij, W.; Quattrocchio, F. Flavonoids: A colorful model for the regulation and evolution of biochemical pathways. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, G.; Francis, F. Anthocyanins in grapes and grape products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1995, 35, 341–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkel-Shirley, B. Flavonoid biosynthesis. A colorful model for genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, and biotechnology. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, J.; Borges, F. Wine and grape polyphenols—A chemical perspective. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 3134–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, M.O.; Dokoozlian, N.K.; Krstic, M.P. Cultural practice and environmental impacts on the flavonoid composition of grapes and wine: A review of recent research. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 57, 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.; Mu, L.; Yan, G.L.; Liang, N.N.; Pan, Q.H.; Wang, J.; Reeves, M.J.; Duan, C.Q. Biosynthesis of anthocyanins and their regulation in colored grapes. Molecules 2010, 15, 9057–9091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, H.M.; Schaefer, V.; Levey, D.J. How plant-animal interactions signal new insights in communication. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahama, U. Oxidation of vacuolar and apoplastic phenolic substrates by peroxidase: Physiological significance of the oxidation reactions. Phytochem. Rev. 2004, 3, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombe, B.G.; McCarthy, M. Dynamics of grape berry growth and physiology of ripening. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2000, 6, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cynkar, W.; Cozzolino, D.; Dambergs, R.G. The effect of sample storage and homogenisation techniques on the chemical composition and near infrared spectra of white grapes. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.F.; Fang, Y.L.; Qin, M.Y.; Zhuang, X.F.; Zhang, Z.W. Varietal differences among the phenolic profiles and antioxidant properties of four cultivars of spine grape (Vitis davidii Foex) in Chongyi County (China). Food Chem. 2012, 134, 2049–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obreque-Slier, E.; Peña-Neira, A.; López-Solís, R.; Zamora-Marín, F.; Ricardo-da Silva, J.M.; Laureano, O. Comparative study of the phenolic composition of seeds and skins from Carménère and Cabernet Sauvignon grape varieties (Vitis vinifera L.) during ripening. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2010, 58, 3591–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puértolas, E.; Hernández-Orte, P.; Sladaña, G.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Improvement of winemaking process using pulsed electric fields at pilot-plant scale. Evolution of chromatic parameters and phenolic content of Cabernet Sauvignon red wines. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Montealegre, R.; Romero Peces, R.; Chacón Vozmediano, J.; Martínez Gascueña, J.; García Romero, E. Phenolic compounds in skins and seeds of ten grape Vitis vinifera varieties grown in a warm climate. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordelon, B.P.; Skinkis, P.A.; Howard, P.H. Impact of training system on vine performance and fruit composition of Traminette. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2008, 59, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Falcão, L.D.; Chaves, E.S.; Burin, V.M.; Falcão, A.P.; Gris, E.F.; Bonin, V.; Bordignon-Luiz, M.T. Maturity of Cabernet Sauvignon berries from grapevines grown with two different training systems in a new grape growing region in Brazil. Cienc. Inv. Agr. 2008, 35, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.G.; Wardle, D.A.; Naylor, A.P. Impact of training system, vine spacing, and basal leaf removal on Riesling. Vine performance, berry composition, canopy microclimate, and vineyard labor requirements. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1996, 47, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert, J.A.; Howell, G.S.; Mansfield, T.K. Sampling Vidal blanc grapes. I. Effect of training system, pruning severity, shoot exposure, shoot origin, and cluster thinning on cluster weight and fruit quality. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1983, 34, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P.; Lanier, W.; Brandt, S. Using growing degree days to predict plant stages. In Ag/Extension Communications Coordinator, Communications Services; Montana State University-Bozeman: Bozeman, MT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Peterlunger, E.; Celotti, E.; da Dalt, G.; Stefanelli, S.; Gollino, G.; Zironi, R. Effect of training system on Pinot noir grape and wine composition. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2002, 53, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, A.G.; Wardle, D. Yield component path analysis of Okanagan Riesling vines conventionally pruned or subjected to simulated mechanical pruning. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1993, 44, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.C.; Cheng, G.L. Comparation among trainging systems in Wine Grapevine. J. Fruit Sci. 1994, 11, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bellí, N.; Marín, S.; Coronas, I.; Sanchis, V.; Ramos, A.J. Skin damage, high temperature and relative humidity as detrimental factors for Aspergillus carbonarius infection and ochratoxin A production in grapes. Food Control 2007, 18, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, C.J. Effect of temperature and humidity on the Grape powdery mildew fungus. Phytopathology 1954, 44, 615–626. [Google Scholar]

- Heuvel, J.E.V.; Proctor, J.T.; Sullivan, J.A.; Fisher, K.H. Influence of training/trellising system and rootstock selection on productivity and fruit composition of Chardonnay and Cabernet franc grapevines in Ontario, Canada. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2004, 55, 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Kliewer, W.; Wolpert, J.A.; Benz, M. Trellis and vine spacing effects on growth, canopy microclimate, yield and fruit composition of Cabernet Sauvignon. Int. Symp. Grapevine Physiol. 1997, 526, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandino, A.; Guidoni, S. Anthocyanins, flavonols and hydroxycinnamates: An attempt to use them to discriminate Vitis vinifera L. cv “Barbera”clones. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 230, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J. Phenolic contents and compositions in skins of red wine grape cultivars among various genetic backgrounds and originations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 3492–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamela, C.P.; Falcón, M.S.G.J.; Simal-Gándara, J.S.; Fernández, I.O. Influence of grape variety, vine system and enological treatments on the colour stability of young red wines. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.G.; Wardle, D.A.; Naylor, A.P. Impact of training system and vine spacing on vine performance and berry composition of Chancellor. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1995, 3, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Segade, S.R.; Vázquez, E.S.; Rodríguez, E.I.; Martínez, J.F. Influence of training system on chromatic characteristics and phenolic composition in red wines. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2009, 229, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; He, Y.N.; Yue, T.X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.W. Effects of climatic conditions and soil properties on cabernet sauvignon berry growth and anthocyanin profiles. Molecules 2014, 19, 13683–13703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidoni, S.; Allara, P.; Schubert, A. Effect of cluster thinning on berry skin anthocyanin composition of Vitis vinifera cv. Nebbiolo. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2002, 53, 224–226. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, P.R.; Clingeleffer, P.R. Crop thinning (hand versus mechanical), grape maturity and anthocyanin concentration: Outcomes from irrigated Cabernet Sauvignon (V. vinifera L.) in a warm climate. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2006, 12, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorti, E.; Guidoni, S.; Ferrandino, A.; Novello, V. Effect of different cluster sunlight exposure levels on ripening and anthocyanin accumulation in Nebbiolo grapes. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2010, 61, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Spayd, S.E.; Tarara, J.M.; Mee, D.L.; Ferguson, J. Separation of sunlight and temperature effects on the composition of Vitis vinifera cv. Merlot berries. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2002, 53, 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Tarara, J.M.; Lee, J.; Spayd, S.E.; Scagel, C.F. Berry temperature and solar radiation alter acylation, proportion, and concentration of anthocyanin in Merlot grapes. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2008, 59, 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.J.; Liu, Y.X.; Pan, Q.H.; Cui, X.Y.; Duan, C.Q. Different anthocyanin profiles of the skin and the pulp of Yan73 (Muscat Hamburg × Alicante Bouschet) grape berries. Molecules 2010, 15, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins: Natural colorants with health-promoting properties. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. T 2010, 1, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuyama, S.; Tanzawa, F.; Kobayashi, H. Leaf removal accelerated accumulation of delphinidin-based anthocyanins in “Muscat Bailey A” [Vitis × labruscana (Bailey) and Vitis vinifera (Muscat Hamburg)] grape skin. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2014, 83, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Guan, L.; Fan, P.G.; Li, S.H.; Wu, B.H. Effect of sunlight exclusion at different phenological stages on anthocyanin accumulation in red grape clusters. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2013, 64, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellarin, S.D.; Matthews, M.A.; di Gaspero, G.; Gambetta, G.A. Water deficits accelerate ripening and induce changes in gene expression regulating flavonoid biosynthesis in grape berries. Planta 2007, 227, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roggero, J.; Coen, S.; Ragonnet, B. High performance liquid chromatography survey on changes in pigment content in ripening grapes of Syrah. An approach to anthocyanin metabolism. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1986, 37, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, T.; Saito, N. Recent progress in the chemistry of polyacylated anthocyanins as flower color pigments. Heterocycles 2002, 56, 633–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Neves, G.; Barreiro, L.; Gil, G.; Franco, J.; Ferrer, M.; Moutounet, M.; Carbonneau, A. Anthocyanic composition of Tannat grapes from the south region of Uruguay. Anal. Chim. Acta 2004, 513, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiloglu, O. Influence of some cultural practices on yield, fruit quality and individual anthocyanins of table grape cv. “Horoz Karasi”. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2011, 21, 240–245. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, G.; Fukuoto, L.; Delaquis, P.; Girard, B.; Ewert, B. Anthocyanins, phenolics, and color of Cabernet franc, Merlot, and Pinot noir wines from British Columbia. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 1999, 47, 4009–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Regules, A.; Romero-Cascales, I.; López-Roca, J.M.; Ros-García, J.M.; Gómez-Plaza, E. Anthocyanin fingerprint of grapes: Environmental and genetic variations. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2006, 86, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.W. Ampelography; Xi’an Map Press: Xian, China, 2000; pp. 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Desaymard, P. Notations et methodes de notations en phytopharmacie. Phytiatrie-Phytopharm 1968, 17, 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- China National Standardization Administration. Ampeliology Analytical Methods of Wines and Fruit Wine; GB/T 15038; China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- De Villiers, A.; Vanhoenacker, G.; Majek, P.; Sandra, P. Determination of anthocyanins in wine by direct injection liquid chromatography-diode array detection-mass spectrometry and classification of wines using discriminant analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1054, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Sinelnikov, I.V.; Han, B.; Wishart, D.S. MetaboAnalyst 3.0—Making metabolomics more meaningful. Nucl. Acids Res. 2015, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

© 2015 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, M.-Y.; Chi, M.; Tang, Y.-H.; Song, C.-Z.; Xi, Z.-M.; Zhang, Z.-W. Effect of Three Training Systems on Grapes in a Wet Region of China: Yield, Incidence of Disease and Anthocyanin Compositions of Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon. Molecules 2015, 20, 18967-18987. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules201018967

Liu M-Y, Chi M, Tang Y-H, Song C-Z, Xi Z-M, Zhang Z-W. Effect of Three Training Systems on Grapes in a Wet Region of China: Yield, Incidence of Disease and Anthocyanin Compositions of Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon. Molecules. 2015; 20(10):18967-18987. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules201018967

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Mei-Ying, Ming Chi, Yong-Hong Tang, Chang-Zheng Song, Zhu-Mei Xi, and Zhen-Wen Zhang. 2015. "Effect of Three Training Systems on Grapes in a Wet Region of China: Yield, Incidence of Disease and Anthocyanin Compositions of Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon" Molecules 20, no. 10: 18967-18987. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules201018967

APA StyleLiu, M. -Y., Chi, M., Tang, Y. -H., Song, C. -Z., Xi, Z. -M., & Zhang, Z. -W. (2015). Effect of Three Training Systems on Grapes in a Wet Region of China: Yield, Incidence of Disease and Anthocyanin Compositions of Vitis vinifera cv. Cabernet Sauvignon. Molecules, 20(10), 18967-18987. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules201018967