Carboxylated Acyclonucleosides: Synthesis and RNase A Inhibition

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of Nucleosides

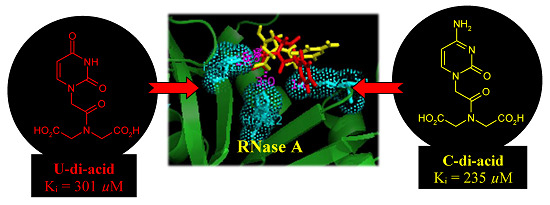

2.2. RNase A Inhibition

| Inhibitor | Ki * (μM) |

|---|---|

| U-ol-acid (8) | 454 ± 9 |

| C-ol-acid (18) | 356 ± 7 |

| U-di-acid (10) | 301 ± 15 |

| C-di-acid (21) | 235 ± 9 |

| Amino Acid Residue | ASA (Å2) in RNase A | ΔASA (Å2) for Different Inhibitors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-ol-Acid (8) | C-ol-Acid (18) | U-di-Acid (10) | C-di-Acid (21) | ||

| Lys 7 | 88.03 | 42.88 | 41.75 | 29.62 | 43.82 |

| His 12 | 12.64 | 7.09 | 7.76 | 9.21 | 7.53 |

| Arg 39 | 142.03 | 25.81 | 29.72 | 5.06 | 30.79 |

| Lys 41 | 36.39 | 26.80 | 31.58 | 33.00 | 31.31 |

| His 119 | 85.05 | 33.62 | 28.29 | 26.69 | 26.64 |

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General Methods

3.2. General Procedure for Carboxylic Acid–Amine Coupling Reaction

3.3. General Procedure for Deprotection of –TBDMS Group

3.4. General Procedure for the Deprotection of –BOC Group/Simultaneous Deprotection of –BOC Group and –TBDMS Group

3.5. General Procedure for Ester Hydrolysis

3.6. Comparative Agarose Gel-Based Assay

3.7. Inhibition Kinetics with RNase A

3.8. Circular Dichroism Measurements

3.9. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

3.10. FlexX Docking

3.11. Accessible Surface Area Calculations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D’Alessio, G. The superfamily of vertebrate-secreted ribonucleases. In Ribonucleases; Nicholson, A.W., Ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Loverix, S.; Steyaert, J. Ribonucleases: from prototypes to therapeutic targets. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, M.; Libra, M.; Callari, D.; Sinatra, F.; Spada, D.; Noto, D.; Emmanuele, G.; Romano, F.; Averna, M.; Pezzino, F.M.; et al. Bovine seminal ribonuclease is cytotoxic for both malignant and normal telomerase-positive cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2005, 27, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zrinski, R.T.; Dodig, S. Eosinophil cationic protein-current concept and controversies. Biochem. Med. 2011, 21, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ibaragi, S.; Hu, G. Angiogenin as a molecular target for the treatment of prostate cancer. Curr. Cancer Ther. Rev. 2011, 7, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, E.F.; Ng, T.B. Ribonucleases of different origins with a wide spectrum of medicinal applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1815, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leland, P.A.; Schultz, L.W.; Kim, B.; Raines, R.T. Ribonuclease A variants with potent cytotoxic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 10407–10412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leland, P.A.; Staniszewski, K.E.; Park, C.; Kelemen, B.R.; Raines, R.T. The ribonucleolytic activity of angiogenin. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raines, R.T. Ribonuclease A. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1045–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, G.; Feng, J.A.; Kuster, D.J. Back to the future: ribonuclease A. Biopolymers 2007, 90, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, R.; Weremowicz, S.; Riordan, J.F.; Vallee, B.L. Ribonucleolytic activity of angiogenin: Essential histidine, lysine, and arginine residues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 8783–8787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamann, K.J.; Barker, R.L.; Loegering, D.A.; Pease, L.R.; Gleich, G.L. Sequence of human eosinophil-derived neurotoxin cDNA: Identity of deduced amino acid sequence with human nonsecretory ribonucleases. Gene 1989, 83, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagné, D.; Charest, L.; Morin, S.; Kovrigin, E.L.; Doucet, N. Conservation of flexible residue clusters among structural and functional enzyme homologues. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 44289–44300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiti, T.K.; De, S.; Dasgupta, S.; Pathak, T. 3'-N-Alkylamino-3'-deoxy-ara-uridines: A new class of potential inhibitors of ribonuclease A and angiogenin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidas, D.D.; Maiti, T.K.; Samanta, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Pathak, T.; Zographos, S.E.; Oikonomakos, N.G. The binding of 3'-N-piperidine-4-carboxyl-3'-deoxy-ara-uridine to ribonuclease A in the crystal. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 6055–6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debnath, J.; Dasgupta, S.; Pathak, T. Inhibition of ribonuclease A by nucleoside-dibasic acid conjugates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 6491–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debnath, J.; Dasgupta, S.; Pathak, T. Comparative inhibitory activity of 3'- and 5'-functionalized nucleosides on ribonuclease A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 8257–8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Pathak, T. 5'-modified pyrimidine nucleosides as inhibitors of ribonuclease A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 6491–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, D.; Samanta, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Pathak, T. 3'-Oxo-, amino-, thio-, and sulfone-acetic acid modified thymidines: Effect of increased acidity on ribonuclease A inhibition. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 4634–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, D.; Samanta, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Pathak, T. Synthesis of 5'-carboxymethylsulfonyl-5'-deoxyribonucleosides under mild hydrolytic conditions: A new class of acidic nucleosides as inhibitors of ribonuclease A. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 2214–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.; Dasgupta, S.; Pathak, T. Ribonuclease A inhibition by carboxymethylsulfonyl-modified xylo- and arabinopyrimidines. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 2138–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.G.; Hammes, G.G.; Walz, F.G. Binding of phosphate ligands to ribonuclease A. Biochemistry 1968, 7, 1637–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walz, F.G. Kinetic and equilibrium studies on the interaction of ribonuclease A and 2'-deoxyuridine 3'-phosphate. Biochemistry 1971, 10, 2156–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, N.; Shapiro, R.; Vallee, B.L. 5'-Diphosphoadenosine-3'-phosphate is a potent inhibitor of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 231, 671–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonidas, D.D.; Shapiro, R.; Irons, L.I.; Russo, N.; Acharya, K.R. Crystal structures of ribonuclease A complexes with 5'-diphosphoadenosine 3'-phosphate and 5'-diphosphoadenosine 2'-phosphate at 1.7 Å resolution. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 5578–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonidas, D.D.; Shapiro, R.; Irons, L.I.; Russo, N.; Acharya, K.R. Towards rational design of ribonuclease inhibitors: High resolution crystal structure of a ribonuclease A complex with a potent 3',5'-pyrophosphate-linked dinucleotide inhibitor. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 10287–10297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, N.; Shapiro, R. Potent inhibition of mammalian ribonucleases by 3',5'-pyrophosphate-linked nucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 14902–14908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonidas, D.D.; Chavali, G.B.; Oikonomakos, N.G.; Chrysina, E.D.; Kosmopoulou, M.N.; Vlassi, M.; Frankling, C.; Acharya, K.R. High-resolution crystal structures of ribonuclease A complexed with adenylic and uridylic nucleotide inhibitors. Implications for structure-based design of ribonucleolytic inhibitors. Protein Sci. 2003, 12, 2559–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Jenkins, J.L.; Jardine, A.M.; Shapiro, R. Inhibition of mammalian ribonucleases by endogenous adenosine dinucleotides. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 300, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, C.L.; Thiyagarajan, N.; Sweeney, R.Y.; Guy, M.P.; Kelemen, B.R.; Acharya, K.R.; Raines, R.T. Binding of non-natural 3'-nucleotides to ribonuclease A. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatzopoulos, G.N.; Leonidas, D.D.; Kardakaris, R.; Kobe, J.; Oikonomakos, N.G. The binding of IMP to ribonuclease A. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 3988–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakovlev, G.I.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Makarov, A.A. Ribonuclease inhibitors. Mol. Biol. 2006, 40, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogués, M.V.; Vilanova, M.; Cuchillo, C.M. Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A as a model of an enzyme with multiple substrate binding sites. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1253, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Findlay, D.; Herries, D.G.; Mathias, A.P.; Rabin, B.R.; Ross, C.A. The active site and mechanism of action of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease. Nature 1961, 190, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuchillo, C.M.; Nogués, M.V.; Raines, R.T. Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease: Fifty years of the first enzymatic reaction mechanism. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 7835–7841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, R.B. The Organic Chemistry of Drug Design and Drug Action, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2004; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Chen, R. Synthesis of novel phosphonotripeptides containing uracil or thymine group. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2001, 176, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazgui, O.; Boëns, B.; Teste, K.; Vergaud, J.; Trouillas, P.; Zerrouki, R. One-pot and catalyst-free amidation of ester: A matter of non-bonding interactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 6796–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcheddu, A.; Giacomelli, G.; Piredda, I.; Carta, M.; Nieddu, G. A practical and efficient approach to PNA monomers compatible with Fmoc-mediated solid-phase synthesis protocols. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 34, 5786–5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, S.; Novetta-dellen, A.; Neault, J.F.; Diamantoglou, S.; Tajmir-riahi, H.A. 3'-azido-3'-deoxythymidine binding to ribonuclease A: Model for drug-protein interaction. Biopolymers 2003, 72, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, K.S.; Maiti, T.K.; Mandal, A.; Dasgupta, S. Copper complexes of (-)-epicatechin gallate and (-)-epigallactocatechin gallate act as inhibitors of ribonuclease A. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 4703–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, K.S.; Debnath, J.; Dutta, P.; Sahoo, B.K.; Dasgupta, S. Exploring the potential of 3'-O-carboxy esters of thymidine as inhibitors of ribonuclease A and angiogenin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 2819–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Basak, A.; Dasgupta, S. Synthesis and ribonuclease A inhibition activity of resorcinol and phloroglucinol derivatives of catechin and epicatechin: Importance of hydroxyl groups. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 6538–6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathy, D.R.; Roy, A.S.; Dasgupta, S. Complex formation of rutin and quercetin with copper alters the mode of inhibition of ribonuclease A. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 3270–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sela, M.; Anfinsen, C.B. Some spectrophotometric and polarimetric experiments with ribonucleases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1957, 24, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmore, L.; Wallace, B.A. DICHROWEB, an online server for protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Borron, J.C.; Escribano, J.; Jimenez, M.; Iborra, J.L. Quantitative determination of tryptophanyl and tyrosyl residues of proteins by second-derivative fluorescence spectroscopy. Anal. Biochem. 1982, 125, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Xie, M.X.; Zheng, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.Y.; Cheng, X. Spectroscopic studies on the interaction of cinnamic acid and its hydroxyl derivatives with human serum albumin. J. Mol. Struct. 2004, 692, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rarey, M.; Kramer, B.; Lengauer, T.; Klebe, G. A fast flexible docking method using an incremental construction algorithm. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 261, 470–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W.L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System; DeLano Scientific: San Carlos, CA, USA, 2004. Available online: http://pymol.sourceforge.net/.

- Sample Availability: Samples are not available from authors.

© 2015 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chakraborty, K.; Dasgupta, S.; Pathak, T. Carboxylated Acyclonucleosides: Synthesis and RNase A Inhibition. Molecules 2015, 20, 5924-5941. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules20045924

Chakraborty K, Dasgupta S, Pathak T. Carboxylated Acyclonucleosides: Synthesis and RNase A Inhibition. Molecules. 2015; 20(4):5924-5941. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules20045924

Chicago/Turabian StyleChakraborty, Kaustav, Swagata Dasgupta, and Tanmaya Pathak. 2015. "Carboxylated Acyclonucleosides: Synthesis and RNase A Inhibition" Molecules 20, no. 4: 5924-5941. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules20045924

APA StyleChakraborty, K., Dasgupta, S., & Pathak, T. (2015). Carboxylated Acyclonucleosides: Synthesis and RNase A Inhibition. Molecules, 20(4), 5924-5941. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules20045924