Eosin Removal by Cetyl Trimethylammonium-Cloisites: Influence of the Surfactant Solution Type and Regeneration Properties

Abstract

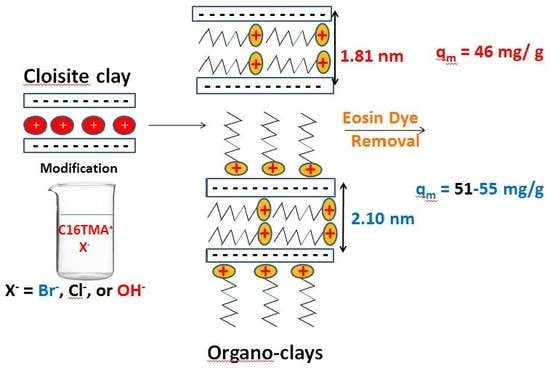

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of Organoclays

2.1.1. Elemental Analysis

2.1.2. Powder XRD Data

2.1.3. FTIR Data

2.1.4. Solid 13C-CP NMR

2.1.5. TGA Data

2.1.6. Nitrogen Adsorption

2.1.7. SEM Studies

2.1.8. Thermal Stability

2.2. Removal of Eosin Dye

2.2.1. Effect of Initial Concentration

2.2.2. Effect of Surfactant Content

2.2.3. Effect of Removal Temperature

2.2.4. Effect of Heating Temperature of Organoclays

2.2.5. Maximum Removal Amount

2.3. Regeneration Tests

2.4. Alternative Approach

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

3.2. Modification of Organo-Clays

3.3. Effect of Washing Solution

3.4. Chemical Stability

3.5. Eosin Removal

3.6. Regeneration Process

3.7. Characterization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goswami, K.B.; Bisht, P.S. The Role of water resources in socio-economic development. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2017, 5, 1669–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Somlyody, L.; Varis, O. Freshwater under pressure. Int. Rev. Environ. Strateg. 2006, 6, 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.; Lall, U. Water and economic development: The role of interannual variability and a framework for resilience. Nat. Resour. Forum. 2006, 30, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisschops, I.; Spanjers, H. Literature review on textile wastewater characterization. Environ. Technol. 2003, 24, 1399–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zollinger, H. Color Chemistry: Syntheses, Properties and Applications of Organic Dyes and Pigments; VCH Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh Babu, B.; Parande, A.K.; Raghu, S.; Prem Kumar, T. Textile technology. Cotton Textile Processing: Waste Generation and Effluent Treatment. J. Cotton Sci. 2007, 11, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Rearick, W.A.; Farias, L.T.; Goettsch, H.B.G. Water and salt reuse in the dyehouse. Text. Chem. Color. 1997, 29, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, R. Textile dyeing industry an environmental hazard. J. Nat. Sci. 2012, 4, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gita, S.; Hussan, H.; Choudhury, T.G. Impact of Textile Dyes Waste on Aquatic Environments and its Treatment. Environ. Ecol. 2017, 35, 2349–2353. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.S.; Durham, B. Integrated water resource management: Looking at the whole picture. Desalination 2003, 156, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, A.; Khatoon, A. Waste management of textiles: A solution to the environmental pollution. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 780–787. [Google Scholar]

- Devi Saini, R. Textile Organic Dyes: Polluting effects and Elimination Methods from Textile Waste Water. Int. J. Chem. Eng. Res. 2017, 9, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Anjaneyulu, Y.; Sreedhara Chary, N.; Suman Raj, D.S. Decolourization of industrial effluents—Available methods and emerging technologies—A review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotech. 2005, 4, 245–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagub, M.T.; Sen, T.K.; Afroze, S.; Ang, H.M. Dye and its removal from aqueous solution by adsorption: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 209, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suteu, D.; Zaharia, C.; Bilba, D.; Muresan, A.; Muresan, R.; Popescu, A. Decolorization wastewaters from the textile industry—Physical methods, chemical methods. Ind. Text. 2009, 60, 254–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, R. Adsorption of dye eosin from an aqueous solution on two different samples of activated carbon by static batch method. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2012, 4, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, K.S.; Ramesh, S.T. Removal of dyes using agricultural waste as low-cost adsorbents: A review. Appl. Water Sci. 2013, 3, 773–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Carrott, P.J.M.; Ribeiro Carrott, M.M.L.; Suhas. Low-Cost Adsorbents: Growing Approach to Wastewater Treatment—A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 39, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katheresan, V.; Kansedo, J.; Lau, S.Y. Efficiency of various recent wastewater dye removal methods: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4676–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Agnihotri, R.; Wasewar, K.L.; Uslu, H.; Yoo, C.K. Status of adsorptive removal of dye from textile industry effluent. Desalin. Water Treat. 2012, 50, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, A.; Iqbal, M.; Javed, A.; Aftab, K.; Nazli, Z.H.; Bhatti, H.N.; Nouren, S. Dyes adsorption using clay and modified clay: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 256, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngulube, T.; Gumbo, J.R.; Masindi, V.; Maity, A. An update on synthetic dyes adsorption onto clay based minerals: A state-of-art review. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 191, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemo, A.A.; Adeoye, I.O.; Bello, O.S. Adsorption of dyes using different types of clay: A review. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Rusmin, R.; Ugochukwu, U.C.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Manjaiah, K.M. Modified clay minerals for environmental applications. In Modified Clay and Zeolite Nanocomposite Materials; Mercurio, M., Sarkar, B., Langell, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna, K.R.; Viraraghavan, T. Dye removal using low cost adsorbents. Water Sci. Technol. 1997, 36, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitrakar, R.; Makita, Y.; Sonoda, A.; Hirotsu, T. Adsorption of trace levels of bromate from aqueous solution by organo-montmorillonite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2011, 51, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Cruz, M.; Sanchez-Martin, M.; Andrades, M.; Sanchez-Camazano, M. Modification of clay barriers with a cationic surfactant to improve the retention of pesticides in soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 139, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafees, M.; Waseem, A. Organoclays as Sorbent Material for Phenolic Compounds: A Review. Clean Soil Air Water 2014, 42, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guegan, R. Organoclay applications and limits in the environment. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2019, 22, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paiva, L.B.; Morales, A.R.; Valenzuela Diaz, F.R. Organoclays: Properties, preparation and applications. Appl. Clay Sci. 2008, 42, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Ayoko, G.A.; Frost, R.L. Application of organoclays for the adsorption of recalcitrant organic molecules from aqueous media. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 354, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Cui, B.; Li, D. Mechanism of adsorption of anionic dye from aqueous solutions onto organobentonite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 186, 1758–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, F.; Liu, Y.; Abboudi, M.; Rakass, S.; Oudghiri Hassani, H.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Al-Faze, R. Removal properties of anionic dye eosin by cetyltrimethylammonium organo-clays: The effect of counter-ions and regeneration studies. Molecules 2018, 23, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elemen, S.; Perrin, E.; Kumbasar, A.; Yapar, S. Modeling the adsorption of textile dye on organoclay using an artificial neural network. Dyes. Pigments. 2012, 95, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guégan, R.; Giovanela, M.; Warmont, F.; Motelica-Heino, M. Nonionic organoclay: A ‘Swiss Army knife’ for the adsorption of organic micro-pollutants? J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 437, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, F.; Qin, L.S.; Kiat, Y.Y.; Weirong, Q.; Hian, P.C. Effect of hexadecyltrimethylammonium (C16) counteranions on the intercalation properties of different montmorillonites. Clay Sci. 2006, 12, 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Gallus, L. Surface configuration of sorbed hexadecyltrimethylammonium on kaolinite as indicated by surfactant and counterion sorption, cation desorption, and FTIR. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2005, 264, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, H.; Vaia, R.A.; Krishnamoorti, R.; Farmer, B.L. Self-assembly of alkylammonium chains on montmorillonite: Effect of chain length, head group structure, and cation exchange capacity. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaralingam, P.; Pulikesi, M.; Elango, D.; Ramamurthi, V.; Sivanesan, S. Adsorption of acid dye onto organobentonite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 128, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga, A.C.; Sousa, B.V.; Santana, L.N.L.; Neves, G.A.; Rodrigues, M.G.F. Study of different methods in the preparation of organoclays from the bentonite with application in the petroleum industry. Braz. J. Pet. Gas 2007, 1, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kooli, F. Effect of C16 contents on the thermal stability of organo-bentonites: In situ X-ray diffraction analysis. Thermochim. Acta 2013, 551, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafees, M.; Waseem, A.; Khan, A.R. Comparative study of laterite and bentonite based organoclays: Implications of hydrophobic compounds remediation from aqueous solutions. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 681769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes, A.; Bernat, J.L.; Diez-Masa, J.C. Determination of critical micelle concentration values using capillary electrophoresis instrumentation. Anal. Chem. 1997, 69, 4271–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goronja, J.M.; Ležaić, A.M.; Janošević; Dimitrijević, B.M.; Malenović, A.M.; Stanisavljev, R.; Pejić, N.D. Determination of critical micelle concentration of cetyltrimethyl-ammonium bromide: Different procedures for analysis of experimental data. Chem. Ind. 2016, 70, 485–492. [Google Scholar]

- Ulmius, J.; Lindman, B.; Lindblom, G.; Drakenberg, T. 1H, 13C, 35CI, and 79Br NMR of Aqueous Hexadecyltrimethylammonium Salt Solutions: Solubilization, Viscoelasticity, and Counterion Specificity. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1978, 65, 66–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, F.; Yan, L. Chemical and thermal properties of organoclays derived from highly stable bentonite in sulfuric acid. Appl. Clay Sci. 2013, 83–84, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, F.; Khimyak, Y.Z.; Alshahateet, S.F.; Chen, F. Effect of the acid activation levels of montmorillonite clay on the cetyltrimethylammonium cations adsorption. Langmuir 2005, 21, 8717–8723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, F.; Liu, Y.; Abboudi, M.; Oudghiri Hassani, H.; Rakass, S.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Al-Wadaani, F. Waste bricks applied as removal agent of Basic Blue 41 from aqueous solution: Base treatment and their regeneration efficiency. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selsted, M.E.; Becker, H.W. Eosin Y: A reversible stain for detecting electrophoretically resolved protein. Anal. Biochem. 1986, 155, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Chatterjee, B.P.; Das, A.R.; Guha, A.K. Adsoprtion of a model anionic dye, eosin Y, from aqueous solution by chitosan hydrobeads. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 288, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.H.; Bando, Y.; Shen, G.Z.; Golberg, D. Thickness-Dependent Photocatalytic Performance of ZnO Nanoplatelets. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 15146–15151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooksey, C. Quirks of dye nomenclature. 10. Eosin Y and its close relatives. Biotech. Histochem. 2018, 93, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, F.; Liu, Y.; Abboudi, M.; Rakass, S.; Oudghiri Hassani, H.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Al-Faze, R. Application of Organo-Magadiites for the Removal of Eosin Dye from Aqueous Solutions: Thermal Treatment and Regeneration. Molecules 2018, 23, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Vianna, M.M.G.; Dweck, J.F.J.; Kozievitch, V.F.; Valenzuela-Diaz, F.R.; Büchler, P.M. Characterization and study of sorptive properties of differently prepared organoclays from a Brazilian natural bentonite. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2005, 82, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisam, H.; Hoidy, M.B.A.; Jaffar Al Mulla, E.A.; Bt Ibrahim, N.A. Synthesis and Characterization of Organoclay from Sodium Montmorillonite and Fatty Hydroxamic Acids. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2009, 6, 1567–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes-Uc, J.M.; Cauich-Rodrıguez, J.V.; Vazquez-Torres, H.; Garfias-Mesıas, L.F.; Paul, D.R. Thermal degradation of commercially available organoclays studied by TGA–FTIR. Thermochim. Acta 2007, 457, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasai, R.; Hotta, Y.; Itoh, H. Preparation of organoclay having titania nano-crystals ininterlayer hydrophobic field and its characterization. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2008, 116, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhtiyarova, G.A.; Özcan, A.S.; Gök, Ö.; Özcan, A. Characterization of natural- and organobentonite by XRD, SEM, FT-IR and thermal analysis techniques and its adsorption behaviour in aqueous solutions. Clay Miner. 2012, 47, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, P.; Qing, Y. Organoclays prepared from montmorillonites with different cation exchange capacity and surfactant configuration. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 48, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narine, D.R.; Guy, R.D. Interactions of some large organic cations with bentonite in dilute aqueous systems. Clays Clay Miner. 1981, 29, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, T.; Guégan, R.; Thiebault, T.; Le Milbeau, C.; Muller, F.; Teixeira, V.; Giovanela, M.; Boussafir, M. Adsorption of diclofenac onto organoclays: Effects of surfactant and environmental (pH and temperature) conditions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 323, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Han, Y.C.; Zhang, J.L.; Wang, L.X.; Song, J. Thermodynamic modeling of CTAB aggregation in water-ethanol mixed solvents. Colloid J. 2006, 68, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Han, Y.C.; Zhang, J.L.; Wang, B.G. Effect of ethanol on the aggregation properties of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide surfactant. Colloid J. 2005, 67, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, P.W. Crystalline swelling of organo-modified clays in ethanol–water solutions. Appl. Clay Sci. 2004, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, F.; Liu, Y.; Hbaieb, K.; Ching, O.Y.; Al-Faze, R. Characterization of organo-kenyaites: Thermal stability and their effects on eosin removal characteristics. Clay Miner. 2018, 53, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuoli, P.T.; Piazza, D.; Scienza, L.C.; Zattera, A.J. Preparation and characterization of montmorillonite modified with 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 87, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.R.; Zeng, Q.H.; Yu, A.B.; Lu, G.Q. The interlayer swelling and molecular packing in organoclays. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 292, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, F. Organo-bentonites with improved cetyltrimethylammonium contents. Clay Miner. 2014, 49, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.A.; Rajesh, S.; Somani, R.S.; Hari, C.; Bajaj, H.C.; Jasra, R.V. Synthesis of organoclays with controlled particle size and whiteness from chemically created indian bentonite. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 1677–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.C.; Stroeve, P. Polymer-Layered Silicate and Silica Nanocomposites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vaia, R.A.; Teukolsky, R.K.; Giannelis, E.P. Interlayer structure and molecular environment of alkylammonium layered silicates. Chem. Mater. 1994, 6, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, N.V.; Vasudevan, S. Conformation of Methylene Chains in an Intercalated Surfactant Bilayer. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ishida, H. Concentration-dependent conformation of alkyl tail in the nanoconfined space: Hexadecylamine in the silicate galleries. Langmuir 2003, 19, 2479–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madejova, J. FT-IR techniques in clay mineral studies. Vibrat. Spectrosc. 2003, 31, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.Z.; Johnston, C.T.; Parker, P.; Agnew, S.F. Infrared study of water sorption on Na-, Li-, Caand Mg- Exchanged (SWy-1and SAz-1) montmorillonite. Clays Clay Miner. 2000, 48, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Messabeb-Ouali, A.; Benna-Zayani, M.; Kbir-Ariguib, N.; Trabelsi-Ayadi, M. Physicochimical characterisation of organophilic clay. Phys. Procedia 2009, 2, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.C.; Wong, N.B.; Tanner, P.A. A Fourier Transform IR Study of the Phase Transitions and Molecular Order in the Hexadecyltrimethylammonium Sulfate/Water System. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 186, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcana, A.; Omero glu, C.; Erdogan, Y.; Ozcana, A.S. Modification of bentonite with a cationic surfactant: And adsorption study of textile dye Reactive Blue 19. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 140, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; He, H.; Zhu, L.; Wen, X.; Deng, F. Characterization of organic phase in the interlayer of montmorillonite using FTIR and 13C NMR. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 286, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rožić, M.; Miljanić, S. Sorption of HDTMA cations on Croatian natural mordenite tuff. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 185, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfeky, S.A.; Mahmoud, S.E.; Youssef, A.F. Applications of CTAB modified magnetic nanoparticles for removal of chromium (VI) from contaminated water. J. Adv. Res. 2017, 8, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casal, H.L.; Mantsch, H.H.; Cameron, D.G.; Snyder, R.G. Interchain vibrational coupling in phase II (hexagonal) n-alkanes. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi-Faridi, A.; Guggenheim, S. Crystal Structure of Tetramethylammonium-Exchanged Vermiculite. Clays Clay Miner. 1997, 45, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Frost, L.R.; Zhu, J. Infrared study of HDTAM+ intercalated montmorillonite. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2004, 60, 2853–2859. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.Q.; Liu, J.; Exarhos, G.J.; Flanigan, K.Y.; Bordia, R. Conformation heterogeneity and mobility of surfactant molecules in intercalated clay minerals studied by Solid-State NMR. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 2810–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, F.; Magussin, P.C.M.M. Adsorption Studies of cetyltrimethylammonium ions on an acid-activated smectite, and their thermal stability. Clay Miner. 2005, 40, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Q.; Liu, J.; Exarhos, G.J.; Bunker, B.C. Investigation of the structure and dynamics of surfactant molecules in mesophase silicates using solid-state13C NMR. Langmuir 1996, 12, 2663–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Chen, H.T.; Escoto, J.L.V.; Lin, V.S.Y.; Pruski, M. Template removal and thermal stability of organically functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 4319–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonutti, R.; Comotti, A.; Bracco, S.; Sozzani, P. Surfactant Organization in MCM-41 Mesoporous Materials As Studied by 13C and 29Si Solid-State NMR. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Feng, J.; Che, S. An insight into the role of the surfactant CTAB in the formation of microporous molecular sieves. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 3612–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Frost, R.L.; Deng, F.; Zhu, J.; Wen, X.; Yuan, P. Conformation of surfactant molecules in the interlayer of montmorillonite studied by 13C MAS NMR. Clays Clay Miner. 2004, 52, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapides, I.; Borisover, M.; Yariv, S. Thermal analysis of hexadecyltrimethylammonium-montmorillonites: Part 2. Thermo-XRD spectroscopy- analysis. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2011, 105, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, J. Qualitative and quantitative characterization of Brazilian natural and organophilic clays by thermal analysis. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2008, 92, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Frost, R.L.; He, H. Thermal stability of octadecyltrimethylammonium bromide modified montmorillonite organoclay. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 311, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Onal, M.; Sarikaya, Y. Thermal behavior of a bentonite. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2007, 90, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozaka, M.; Domka, L. Adsorption of the quaternary ammonium salts on montmorillonite. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2004, 65, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, F. Thermal stability investigation of organo-acid-activated clays by TGMS and in situ XRD techniques. Thermochim. Acta 2009, 486, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternik, D.; Gładysz-Płaska, A.G.; Grabias, E.; Majdanl, M.; Knauer, W. A thermal, sorptive and spectral study of HDTMA-bentonite loaded with uranyl phosphate. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 129, 1277–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, Y.; Ayoko, G.A.; Kristof, J.; Horvath, E.; Frost, R.L. A thermoanalytical assessment of an organoclay. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2012, 107, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, H.; Yuan, P.; Liu, H.; Liu, D.; Zhou, X. Thermal decomposition of long-chain fatty acids and its derivative in the presence of montmorillonite: A thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) investigation. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Sun, R. Rapid modification of montmorillonite with novel cationic Gemini surfactants and its adsorption for methyl orange. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2011, 130, 1220–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.F.; Mallavarapu, M.; Naidu, R. Preparation, characterization of surfactants modified clay minerals and nitrate adsorption. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 48, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mallakpour, S.; Dinari, M. Preparation and characterization of new organoclays using natural amino acids and Cloisite Na+. Appl. Clay Sci. 2011, 51, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Frost, R.L.; He, H. Modification of the surfaces of Wyoming montmorillonite by the cationic surfactants alkyl trimethyl, dialkyl dimethyl and trialkylmethylammonium bromides. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 305, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Choo, H.; Bhatt, A.; Burns, S.E.; Bate, B. Review of the fundamental geochemical and physical behaviors of organoclays in barrier applications. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 142, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soule, N.M.; Burns, S.E. Effects of organic cation structure on behavior of organobentonites. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. 2001, 127, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, B.; Choo, H.; Burns, S. Dynamic properties of fine-grained soils engineered with a controlled organic phase. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2013, 53, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.P.S.; Estevão, L.R.M.; Nascimento, R.S.V. Effect of clays on the fire-retardant properties of a polyethylenic copolymer containing intumescent formulation. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2008, 9, 024408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Forestier, L.; Muller, F.; Villieras, F.; Pelletier, M. Textural and hydration properties of a synthetic montmorillonite compared with a natural Na-exchanged clay analogue. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 48, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, H.P.; Frost, R.L.; Bostrom, T.; Yuan, P.; Duong, L.; Yang, D.; Yun, X.F.; Kloprogge, J.T. Changes in the morphology of organoclays with HDTMA+ surfactant loading. Appl. Clay Sci. 2006, 31, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, W.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, L. Sorption characteristics of nitrosodiphenylamine (NDPhA) and diphenylamine (DPhA) onto organo-bentonite from aqueous solution. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 240, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Juang, L.C.; Lee, C.K.; Hsu, T.C.; Lee, J.F.; Chao, H.P. Effects of exchanged surfactant cations on the pore structure and adsorption characteristics of montmorillonite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 280, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhou, Q.; Martens, W.N.; Kloprogge, T.J.; Yuan, P.; Xi, Y.; Frost, R.L. Microstructure of HDTMA+-modified montmorillonite and its influence on sorption characteristics. Clays Clay Miner. 2006, 54, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertagnolli, C.; Silva, M.G.C. Characterization of Brazilian Bentonite Organoclays as sorbents of petroleum-derived fuels. Mater. Res. 2012, 15, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burris, D.R.; Antworth, C.P. In situ modification of an aquifer material by a cationic surfactant to enhance retardation of organic contaminants. J. Contam. Hydrol. 1992, 10, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, R.S.; Lin, S.H.; Tsao, K.H. Mechanism of sorption of phenols from aqueous solutions onto surfactant-modified montmorillonite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 254, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezrodna, T.; Puchkovska, G.; Styopkin, V.; Baran, J.; Drozd, M.; Danchuk, V.; Kravchuk, A. IR-study of thermotropic phase transitions in cetyltrimethylammonium bromide powder and film. J. Mol. Struct. 2010, 973, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohra, B.; Aicha, K.; Fatima, S.; Nourredine, B.; Zubir, D. Adsoprtion of Direct Red 2 on bentonite modified by cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 136, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akl Ma, Y.A.M.; Al-Awadhi, M.M. Adsorption of acid dyes onto bentonite and surfactant-modified bentonite. J. Anal. Bioanal. Tech. 2013, 4, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wang, A. Adsorption properties of Congo Red from aqueous solution onto surfactant-modified montmorillonite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 160, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.I.; Xi, Y.; Megharaj, M.; Krishnamurti, G.S.; Bowman, M.; Rose, H.; Naidu, R. Bioreactive organoclay: A new technology for environmental remediation. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2102, 42, 435–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Pan, G.; Shen, W. Enhanced sorption of perfluorooctane sulfonate and Cr (VI) on organo montmorillonite: Influence of solution pH and uptake mechanism. Adsorption 2013, 19, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisover, M.; Bukhanovsky, N.; Lapides, I.; Yariv, S. Mild pre-heating of organic cation-exchanged clays enhances their interactions with nitrobenzene in aqueous environment. Adsorption 2010, 16, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.V.; Sivanesan, S. Isotherm parameters for basic dyes onto activated carbon: Comparison of linear and non-linear method. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 129, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Faze, R.; Kooli, F. Eosin removal properties of organo-local clay from aqueous solution. Orient. J. Chem. 2014, 30, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhami, S.; Abrishamkar, M.; Esmaeilzadeh, L. Preparation and Characterization of Diethylenetriamine-montmorillonite and its application for the removal of Eosin Y dye: Optimization, kinetic and isotherm studies. J. Sci. Ind. Res. India 2013, 72, 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, O.S.; Olusegun, O.A.; Njoku, V.O. Fly ash; an alternative to powdered activated carbon for the removal of eosin dye from aqueous solutions. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2013, 27, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, M.S.; Ismaiel, A.M. Sol-gel-gamma alumina nanoparticles assessment of the removal of eosin yellow using: Adsoprtion, kinetic and thermodynamic parameters. J. Encapsul. Adsorp. Sci. 2016, 6, 70–90. [Google Scholar]

- Oyelude, E.O.; Awudza, J.A.M.; Twumasi, S.K. Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic study ofremoval of Eosin yellow from aqueous solution using teak leaf litter powder. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahadat, M.M.; Ismail, S. Regeneration performance of clay-based adsorbents for the removal of industrial dyes: A review. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 24571–24587. [Google Scholar]

- Nanocor. Technical Data, General Information about Nanocore Nanoclay; G-100 (12/04); Nanocor Inc.: Hoffman Estates, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors. |

| Samples | C% | H% | N% | C/N * | Uptake Amount (mmole/g) + |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C16Br salt | 62.62 | 11.67 | 3.87 | 18.87 | - |

| C16BrCN-2.40 | 28.12 | 4.63 | 1.80 | 1.23 (1.44) | |

| C16ClCN-2.40 | 20.47 | 4.36 | 1.30 | 0.90 (1.05) | |

| C16OHCN-2.40 | 18.56 | 3.60 | 1.16 | 0.81(0.95) |

| Samples | C% | H% | N% | C/N * | Uptake Amount (mmol/g) + |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C16ClCN-0.41 | 7.21 | 2.48 | 0.46 | 18.28 | 0.32 (0.34) |

| C16ClCN-0.83 | 12.29 | 2.65 | 0.76 | 18.82 | 0.54 (0.64) |

| C16ClCN-1.20 | 17.66 | 3.78 | 1.09 | 18.90 | 0.77 (0.91) |

| C16ClCN-2.40 | 20.47 | 4.36 | 1.27 | 18.80 | 0.90 (1.05) |

| C16ClCN-3.30 | 22.63 | 4.64 | 1.41 | 18.33 | 0.99 (1.16) |

| C16ClCN-4.80 | 23.79 | 4.81 | 1.47 | 18.88 | 1.04 (1.22) |

| Sample | Spectral Assignment (Shift in ppm) | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Solid C16Br [88] | C1: 68; C2: 32; C3-C14: 30; C15: 27, C16: 24; C17-C19: 54 |  |

| Solid C16Cl [89] | C2: 67.05 (66.80) *; C1: 54.61 (53.14); C15: 36.40 (31.92); C5-C14: 34.70 (29.44); C3: 30.77.29.19 (26.24); C4:27-24 (23.25); C16: 27-24 (22.68); C17: 18.22, 17.10, 16.56, 16.14 (14.12) |  |

| C16Cl-CN | C17: 14.9; 23.7 (C16); 33.2 (C15); 27.4 (C3); 67.8 (N-methyl group (C1); 31.1 (C4-C14) |

| Samples | Tmax (°C) of H2O Molecules | Tmax (°C) of C16+ | Tmax (°C) of Residual C16 and Dehydration | W (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 75 | - | 690 | 85.5 |

| C16Br-CN | 54 | 260 | 580 | 60.77 |

| C16Cl-CN | 45 | 260 | 560 | 70.95 |

| C16OH-CN | 54 | 270 | 590 | 72.91 |

| C16Br | - | 242 | - | 1 |

| Samples | qmax (mg/g) | KL (L/mg) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CN | 2.25 | 0.0035 | 0.9343 |

| C16Br-CN | 55.64 | 0.1332 | 0.9979 |

| C16Cl-CN | 50.50 | 0.0844 | 0.9956 |

| C16OH-CN | 46.66 | 0.0773 | 0.9954 |

| C16Cl-CN-50 | 50.17 | 0.0459 | 0.9915 |

| C16Cl-CN-150 | 50.02 | 0.0371 | 0.9945 |

| C16Cl-CN-200 | 47.56 | 0.0268 | 0.9954 |

| C16Cl-CN-215 | 40.70 | 0.0182 | 0.9953 |

| C16Cl-CN-250 | 31.41 | 0.0135 | 0.9942 |

| C16Cl-CN-300 | 29.42 | 0.0076 | 0.9912 |

| C16Cl-CN-400 | 24.72 | 0.00275 | 0.9902 |

| C16Cl(0.32)*-CN | 19.98 | 0.00542 | 0.9932 |

| C16Cl(0.54)-CN | 42.31 | 0.0621 | 0.9943 |

| C16Cl(0.9)-CN | 46.23 | 0.0684 | 0.9903 |

| C16Cl(1.05)-CN | 46.85 50.50 | 0.0909 0.0844 | 0.9934 0.9959 |

| Samples | qm (mg/g) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Organo-CN clays | 34.96 to 51.81 | This study |

| Organo-PG clays | 75.11 to 94.20 | [33] |

| Organo-magadiites | 69.54 | [53] |

| Organo-local clays | 48.66 | [125] |

| Organo-kenyaites | 48.01 | [66] |

| 5Diethylentriamine-montmorillonite | 11.90 | [126] |

| Raw fly ash | 43.48 | [127] |

| Alumina nanoparticles | 47.78 | [128] |

| Teak leaf litter powder | 31.64 | [129] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kooli, F.; Rakass, S.; Liu, Y.; Abboudi, M.; Oudghiri Hassani, H.; Muhammad Ibrahim, S.; Al Wadaani, F.; Al-Faze, R. Eosin Removal by Cetyl Trimethylammonium-Cloisites: Influence of the Surfactant Solution Type and Regeneration Properties. Molecules 2019, 24, 3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24163015

Kooli F, Rakass S, Liu Y, Abboudi M, Oudghiri Hassani H, Muhammad Ibrahim S, Al Wadaani F, Al-Faze R. Eosin Removal by Cetyl Trimethylammonium-Cloisites: Influence of the Surfactant Solution Type and Regeneration Properties. Molecules. 2019; 24(16):3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24163015

Chicago/Turabian StyleKooli, Fethi, Souad Rakass, Yan Liu, Mostafa Abboudi, Hicham Oudghiri Hassani, Sheikh Muhammad Ibrahim, Fahd Al Wadaani, and Rawan Al-Faze. 2019. "Eosin Removal by Cetyl Trimethylammonium-Cloisites: Influence of the Surfactant Solution Type and Regeneration Properties" Molecules 24, no. 16: 3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24163015

APA StyleKooli, F., Rakass, S., Liu, Y., Abboudi, M., Oudghiri Hassani, H., Muhammad Ibrahim, S., Al Wadaani, F., & Al-Faze, R. (2019). Eosin Removal by Cetyl Trimethylammonium-Cloisites: Influence of the Surfactant Solution Type and Regeneration Properties. Molecules, 24(16), 3015. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24163015