Augmenting the Activity of Monoterpenoid Phenols against Fungal Pathogens Using 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde that Target Cell Wall Integrity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Fungi | Fungicide | Key Features (Potentiation of Mycotoxin Production) |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus parasiticus | Anilinopyrimidine | Correlation between fitness parameters and aflatoxigenicity [11] |

| A. parasiticus | Flusilazole | Highly aflatoxigenic, sterol demethylation inhibition-resistant isolates [12] |

| A. parasiticus | Phenylpyrrole | Highly aflatoxigenic, phenylpyrrole resistant isolates [13] |

| Fusarium graminearum | Carbendazim | Increased trichothecene production with carbendazim resistance [14] |

| Fusarium sp. | Strobilurins | Increased deoxynivalenol production by sub-optimal application of strobilurin [9] |

| F. sporotrichioides | Carbendazim | Higher mycotoxin production (T-2 toxin, 4,15-diacetoxyscirpenol, neosolaniol) with carbendazim resistance [15] |

| Penicillium expansum | Tebuconazole, Fludioxonil, etc. | Adverse effect of fitness penalties on the mycotoxigenicity of resistant isolates [16] |

| P. expansum | Benzimidazole | Highly mycotoxigenic field isolates resistant to the benzimidazoles [17] |

| P. verrucosum | Iprodione | Strong induction of mycotoxin biosynthesis by iprodione [18] |

| Aspergillus | Characteristics | Source/References |

|---|---|---|

| A. flavus 3357 | Plant pathogen (aflatoxin), Human pathogen (aspergillosis), Reference aflatoxigenic strain used for genome sequencing | NRRL a [26] |

| A. flavus 4212 | Plant pathogen (aflatoxin), Human pathogen (aspergillosis) | NRRL |

| A. parasiticus 5862 | Plant pathogen (aflatoxin) | NRRL |

| A. parasiticus 2999 | Plant pathogen (aflatoxin) | NRRL |

| A. fumigatus AF293 | Human pathogen (aspergillosis), Parental strain, Reference clinical strain used for genome sequencing | [26,27] |

| A. fumigatus sakAΔ | Human pathogen (aspergillosis), Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) gene deletion mutant derived from AF293 | [27] |

| A. fumigatus mpkCΔ | Human pathogen (aspergillosis), Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) gene deletion mutant derived from AF293 | [28] |

| P. expansum W1 | Plant pathogen (patulin), Parental strain | [29] |

| P. expansum FR2 | Plant pathogen (patulin), Fludioxonil resistant mutant derived from P. expansum W1 | [29] |

| P. expansum W2 | Plant pathogen (patulin), Parental strain | [29] |

| P. expansum FR3 | Plant pathogen (patulin), Fludioxonil resistant mutant derived from P. expansum W2 | [29] |

| Saccharomyces | Characteristics | Source/References |

| S. cerevisiae BY4741 | Model yeast, Parental strain (Mat a his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0) | [30] |

| S. cerevisiae slt2Δ | MAPK mutant in cell wall integrity system derived from BY4741 | [30] |

| S. cerevisiae bck1Δ | MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK) mutant derived from BY4741 | [30] |

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Identification of 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde (2H4M) as the Most Potent Antifungal Benzaldehyde Analog via Yeast Screening: Structure-Activity Relationship

| Benzaldehyde Derivatives | WT | slt2Δ | bck1Δ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2-Methyl-4-methoxybenzaldehyde | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3,5-Dimethoxybenzaldehyde | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2,3-Dimethoxybenzaldehyde | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 2,5-Dimethoxybenzaldehyde | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 2-Methoxybenzaldehyde | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 2,4-Dimethoxybenzaldehyde | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 3-Methoxybenzaldehyde | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| 4-Methoxybenzaldehyde | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| 2,4,5-Trimethoxybenzaldehyde | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 3,4-Dimethoxybenzaldehyde | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 4-Hydroxy-2-methoxybenzaldehyde | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 3,5-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxybenzaldehyde | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Benzaldehyde | 6 | 6 | 6 |

2.2. Growth Recovery of S. cerevisiae bck1Δ and slt2Δ Mutants by Sorbitol

2.3. Chemosensitization Test in S. cerevisiae: Co-Application of Thymol or Carvacrol with 2H4M Augmented the Antifungal Efficacy of Test Compounds in S. cerevisiae

| Yeast Strains Carvacrol | Compounds | MIC Alone | MIC Combined | FICI | MFC Alone | MFC Combined | FFCI |

| S. cerevisiae WT | Carvacrol | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 6.4 b | 3.2 | 0.8 |

| 2H4M | 1.6 | 0.8 | 12.8 c | 3.2 | |||

| S. cerevisiae slt2Δ | Carvacrol | 0.4 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 6.4 | 3.2 | 0.6 |

| 2H4M | 1.6 | 1.6 | 12.8 | 1.6 | |||

| S. cerevisiae bck1Δ | Carvacrol | 0.4 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 6.4 | 3.2 | 0.6 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.8 | 12.8 | 1.6 | |||

| Mean | Carvacrol | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 6.4 | 3.2 | 0.6 |

| 2H4M | 1.3 | 1.1 | 12.8 | 2.1 | |||

| t-test d | Carvacrol | - | p < 0.5 | - | - | p < 0.005 | - |

| 2H4M | - | p < 1.0 | - | - | p < 0.005 | - | |

| Yeast Strains Thymol | Compounds | MIC Alone | MIC Combined | FICI | MFC Alone | MFC Combined | FFCI |

| S. cerevisiae WT | Thymol | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 0.6 |

| 2H4M | 1.6 | 0.8 | 12.8 | 0.8 | |||

| S. cerevisiae slt2Δ | Thymol | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| 2H4M | 1.6 | 0.8 | 12.8 | 12.8 | |||

| S. cerevisiae bck1Δ | Thymol | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

| 2H4M | 1.6 | 0.8 | 12.8 | 12.8 | |||

| Mean | Thymol | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| 2H4M | 1.6 | 0.8 | 12.8 | 8.8 | |||

| t-test d | Thymol | - | p < 0.1 | - | - | p < 0.5 | - |

| 2H4M | - | p = 0.0 | - | - | p < 0.5 | - |

2.4. Chemosensitization Test in Filamentous Fungi: Co-Application of Thymol or Carvacrol with 2H4M

| Fungal Strains | Compounds | MIC Alone | MIC Combined | FICI | MFC Alone | MFC Combined | FFCI |

| A. fumigatus AF293 | Carvacrol | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 12.8 b | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 12.8 c | 1.6 | |||

| A. fumigatus sakAΔ | Carvacrol | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 12.8 | 1.6 | |||

| A. fumigatus mpkCΔ | Carvacrol | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 12.8 | 1.6 | |||

| A. flavus 3357 | Carvacrol | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 1.6 | 0.4 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 3.2 | 0.8 | |||

| A. flavus 4212 | Carvacrol | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 12.8 | 1.6 | 0.4 |

| 2H4M | 1.6 | 0.4 | 3.2 | 0.8 | |||

| A. parasiticus 2999 | Carvacrol | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 6.4 | 1.6 | |||

| A. parasiticus 5862 | Carvacrol | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 6.4 | 1.6 | |||

| P. expansum W1 | Carvacrol | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 12.8 | 1.6 | 0.4 |

| 2H4M | 0.4 | 0.2 | 12.8 | 3.2 | |||

| P. expansum FR2 | Carvacrol | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.4 | 0.2 | 12.8 | 1.6 | |||

| P. expansum W2 | Carvacrol | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 12.8 | 1.6 | |||

| P. expansum FR3 | Carvacrol | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 12.8 | 1.6 | |||

| Mean | Carvacrol | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 11.1 | 1.3 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 9.9 | 1.6 | |||

| t-test d | Carvacrol | – | p < 0.005 | – | – | p < 0.005 | – |

| 2H4M | – | p < 0.005 | – | – | p < 0.005 | – | |

| Fungal Strains | Compounds | MIC Alone | MIC Combined | FICI | MFC Alone | MFC Combined | FFCI |

| A. fumigatus AF293 | Thymol | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 12.8 | 3.2 | |||

| A. fumigatus sakAΔ | Thymol | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 12.8 | 3.2 | |||

| A. fumigatus mpkCΔ | Thymol | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 12.8 | 3.2 | |||

| A. flavus 3357 | Thymol | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 0.6 |

| 2H4M | 1.6 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 0.4 | |||

| A. flavus 4212 | Thymol | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 0.6 |

| 2H4M | 1.6 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 0.4 | |||

| A. parasiticus 2999 | Thymol | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 12.8 e | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 6.4 f | 1.6 | |||

| A. parasiticus 5862 | Thymol | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 6.4 f | 1.6 | |||

| P. expansum W1 | Thymol | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.4 | 0.2 | 12.8 | 1.6 | |||

| P. expansum FR2 | Thymol | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.4 | 0.2 | 12.8 | 1.6 | |||

| P. expansum W2 | Thymol | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 12.8 | 1.6 | |||

| P. expansum FR3 | Thymol | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.8 | 0.4 | 12.8 | 1.6 | |||

| Mean | Thymol | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 8.1 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| 2H4M | 0.9 | 0.4 | 9.9 | 1.8 | |||

| t-test | Thymol | – | p < 0.005 | - | - | p < 0.005 | - |

| 2H4M | – | p < 0.005 | - | - | p < 0.005 | - |

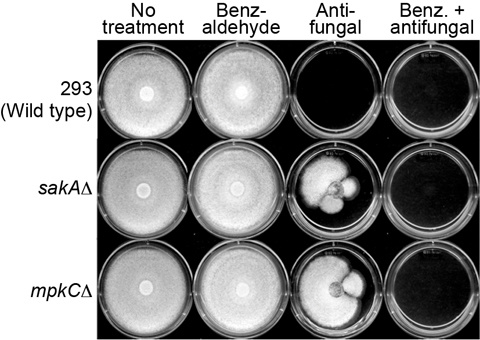

2.5. Overcoming Fludioxonil Tolerance of A. fumigatus MAPK Mutants by 2H4M Co-Treatment

2.6. Antimycotoxigenic Property of 2H4M against A. parasiticus Strains

| Thymol | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | Concentration | AFB1 | AFB2 | AFG1 | AFG2 | Sclerotia |

| A. flavus 3357 | 0.000 | 5.14 ± 0.87 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | – b | – | 6 ± 6 |

| 0.125 | 7.38 ± 0.31 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | – | – | 47 ± 5 | |

| 0.250 | 7.74 ± 1.16 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | – | – | 84 ± 7 | |

| 0.500 | 8.72 ± 0.36 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | – | – | 31 ± 9 | |

| 1.000 | 1.16 ± 0.48 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| A. flavus 4212 | 0.000 | 4.55 ± 0.08 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | – | – | 0 ± 0 |

| 0.125 | 5.86 ± 0.15 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| 0.250 | 6.77 ± 0.38 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | – | – | 3 ± 2 | |

| 0.500 | 7.15 ± 0.12 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| 1.000 | 1.56 ± 0.47 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| A. parasiticus 2999 | 0.000 | 14.46 ± 0.31 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 3.07 ± 0.18 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0 ± 0 |

| 0.125 | 18.80 ± 0.06 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 5.93 ± 0.06 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 171 ± 23 | |

| 0.250 | 23.16 ± 1.26 | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 7.65 ± 0.82 | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 28 ± 13 | |

| 0.500 | 18.19 ± 0.50 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 3.96 ± 0.35 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 1.000 | 0.90 ± 0.44 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0 ± 0 | |

| A. parasiticus 5862 | 0.000 | 15.01 ± 0.92 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 3.39 ± 0.24 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0 ± 0 |

| 0.125 | 18.64 ± 1.60 | 0.49 ± 0.06 | 5.98 ± 0.83 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 166 ± 21 | |

| 0.250 | 22.69 ± 1.38 | 0.69 ± 0.07 | 7.54 ± 0.82 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 17 ± 13 | |

| 0.500 | 16.34 ± 1.49 | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 3.32 ± 0.48 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 1.000 | 0.69 ± 0.22 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0 ± 0 | |

| Carvacrol | ||||||

| Strains | Concentration | AFB1 | AFB2 | AFG1 | AFG2 | Sclerotia |

| A. flavus 3357 | 0.000 | 4.80 ± 0.14 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | – b | – | 2 ± 1 |

| 0.125 | 5.78 ± 0.31 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | – | – | 64 ± 11 | |

| 0.250 | 5.73 ± 0.53 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | – | – | 59 ± 8 | |

| 0.500 | 5.96 ± 0.36 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| 1.000 | 1.23 ± 0.45 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| A. flavus 4212 | 0.000 | 5.51 ± 0.56 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | – | – | 0 ± 0 |

| 0.125 | 6.84 ± 0.66 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | – | – | 1 ± 2 | |

| 0.250 | 7.50 ± 0.66 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | – | – | 8 ± 4 | |

| 0.500 | 6.50 ± 0.29 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| 1.000 | 0.91 ± 0.32 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| A. parasiticus 2999 | 0.000 | 14.02 ± 1.58 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 2.75 ± 0.54 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 1 ± 1 |

| 0.125 | 17.30 ± 0.83 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 3.22 ± 0.27 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 62 ± 4 | |

| 0.250 | 17.38 ± 0.26 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 2.90 ± 0.12 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 46 ± 5 | |

| 0.500 | 19.54 ± 0.88 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 2.20 ± 0.13 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 1.000 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0 ± 0 | |

| A. parasiticus 5862 | 0.000 | 13.92 ± 0.36 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 2.84 ± 0.10 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 1 ± 1 |

| 0.125 | 16.65 ± 0.88 | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 3.19 ± 0.28 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 44 ± 6 | |

| 0.250 | 16.51 ± 1.07 | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 2.68 ± 0.22 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 25 ± 3 | |

| 0.500 | 20.10 ± 0.49 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 2.32 ± 0.10 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 1.000 | 0.12 ± 0.12 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 2H4M | ||||||

| Strains | Concentration | AFB1 | AFB2 | AFG1 | AFG2 | Sclerotia |

| A. flavus 3357 | 0.000 | 4.73 ± 0.23 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | – b | – | 4 ± 3 |

| 0.125 | 5.03 ± 0.35 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| 0.250 | 4.84 ± 0.06 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| 0.500 | NG c | NG | NG | NG | NG | |

| 1.000 | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | |

| A. flavus 4212 | 0.000 | 4.72 ± 0.24 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | – | – | 0 ± 0 |

| 0.125 | 6.58 ± 1.02 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| 0.250 | 5.69 ± 0.55 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | – | – | 0 ± 0 | |

| 0.500 | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | |

| 1.000 | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | |

| A. parasiticus 2999 | 0.000 | 15.92 ± 1.28 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 3.20 ± 0.33 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0 ± 1 |

| 0.125 | 12.80 ± 0.26 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 2.62 ± 0.08 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 0.250 | 10.16 ± 0.79 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 2.23 ± 0.24 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 0.500 | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | |

| 1.000 | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | |

| A. parasiticus 5862 | 0.000 | 14.21 ± 1.02 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 2.91 ± 0.35 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0 ± 1 |

| 0.125 | 12.65 ± 0.53 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 2.65 ± 0.07 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 0.250 | 10.95 ± 1.19 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 2.38 ± 0.43 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0 ± 0 | |

| 0.500 | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | |

| 1.000 | NG | NG | NG | NG | NG | |

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Fungal Strains and Culture Conditions

3.2. Chemicals

3.3. Susceptibility Testing

3.3.1. Agar Plate Bioassay in S. cerevisiae

3.3.2. Agar Plate Bioassay in Aspergillus: Overcoming Fludioxonil Resistance of A. fumigatus sakAΔ and mpkCΔ Mutants

3.3.3. Liquid Bioassay in Filamentous Fungi (CLSI) and S. cerevisiae (EUCAST)

3.4. Growth Recovery Bioassay for S. cerevisiae bck1Δ and slt2Δ Mutants

3.5. Aflatoxin Analysis of Fungal Cultures

3.6. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Denning, D.W. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 26, 781–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.J.; Brookman, J.L.; Denning, D.W. Aspergillus. In Genomics of Plants and Fungi; Prade, R.A., Bohnert, H.J., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, K.A.; Patterson, T.; Denning, D. Aspergillosis. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and therapy. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2002, 16, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roilides, E.; Holmes, A.; Blake, C.; Pizzo, P.A.; Walsh, T.J. Impairment of neutrophil antifungal activity against hyphae of Aspergillus fumigatus in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 167, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.C.; Molyneux, R.J.; Schatzki, T.F. Current research on reducing pre- and post-harvest aflatoxin contamination of US almond, pistachio and walnut. J. Toxicol. Toxin Rev. 2003, 22, 225–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizzell, C.; Elliott, C.T.; Connolly, L. Effects of the mycotoxin patulin at the level of nuclear receptor transcriptional activity and steroidogenesis in vitro. Toxicol. Lett. 2014, 229, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cools, H.J.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E. Exploitation of genomics in fungicide research: Current status and future perspectives. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Possiede, Y.M.; Gabardo, J.; Kava-Cordeiro, V.; Galli-Terasawa, L.V.; Azevedo, J.L.; Glienke, C. Fungicide resistance and genetic variability in plant pathogenic strains of Guignardia citricarpa. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2009, 40, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellner, F.M. Results of long-term field studies into the effect of strobilurin containing fungicides on the production of mycotoxins in several winter wheat varieties. Mycotoxin Res. 2005, 21, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer CropScience. Strobilurin Fungicides Increase DON Levels in Wheat, Reduce Quality. Available online: https://www.bayercropscience.us/~/media/BayerCropScience/Country-United-States-Internet/Documents/News/2014AgIssues/docs/FusariumHeadBlightFeatureStory.ashx (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Markoglou, A.N.; Doukas, E.G.; Malandrakis, A.A. Effect of anilinopyrimidine resistance on aflatoxin production and fitness parameters in Aspergillus parasiticus Speare. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 146, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doukas, E.G.; Markoglou, A.N.; Vontas, J.G.; Ziogas, B.N. Effect of DMI-resistance mechanisms on cross-resistance patterns, fitness parameters and aflatoxin production in Aspergillus parasiticus Speare. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2012, 49, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markoglou, A.N.; Doukas, E.G.; Ziogas, B.N. Phenylpyrrole-resistance and aflatoxin production in Aspergillus parasiticus Speare. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 127, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Yu, J.J.; Zhang, Y.N.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, C.J.; Wang, J.X.; Hollomon, D.W.; Fan, P.S.; Zhou, M.G. Effect of carbendazim resistance on trichothecene production and aggressiveness of Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2009, 22, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Mello, J.P.F.; Macdonald, A.M.C.; Briere, L. Mycotoxin production in a carbendazim-resistant strain of Fusarium sporotrichioides. Mycotoxin Res. 2000, 16, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaoglanidis, G.S.; Markoglou, A.N.; Bardas, G.A.; Doukas, E.G.; Konstantinou, S.; Kalampokis, J.F. Sensitivity of Penicillium expansum field isolates to tebuconazole, iprodione, fludioxonil and cyprodinil and characterization of fitness parameters and patulin production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malandrakis, A.A.; Markoglou, A.N.; Konstantinou, S.; Doukas, E.G.; Kalampokis, J.F.; Karaoglanidis, G.S. Molecular characterization, fitness and mycotoxin production of benzimidazole-resistant isolates of Penicillium expansum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 162, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Heydt, M.; Stoll, D.; Geisen, R. Fungicides effectively used for growth inhibition of several fungi could induce mycotoxin biosynthesis in toxigenic species. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 166, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauvais, A.; Latgé, J.P. Membrane and cell wall targets in Aspergillus fumigatus. Drug Resist. Updat. 2001, 4, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, D.E.; Fields, F.O.; Kunisawa, R.; Bishop, J.M.; Thorner, J. A candidate protein kinase C gene, PKC1, is required for the S. cerevisiae cell cycle. Cell 1990, 62, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, B.B.; Mylonakis, E. Our paths might cross: The role of the fungal cell wall integrity pathway in stress response and cross talk with other stress response pathways. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 1616–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujioka, T.; Mizutani, O.; Furukawa, K.; Sato, N.; Yoshimi, A.; Yamagata, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Abe, K. MpkA-Dependent and -independent cell wall integrity signaling in Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 1497–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlin, D.S. Mechanisms of echinocandin antifungal drug resistance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, L.A.; Lee, K.K.; Munro, C.A.; Gow, N.A. Caspofungin treatment of Aspergillus fumigatus results in ChsG-dependent upregulation of chitin synthesis and the formation of chitin-rich micro-colonies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odds, F.C.; Brown, A.J.; Gow, N.A. Antifungal agents: Mechanisms of action. Trends Microbiol. 2003, 11, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspergillus Comparative Database. Available online: http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/aspergillus_group/MultiHome.html (accessed on 25 August 2015).

- Xue, T.; Nguyen, C.K.; Romans, A.; May, G.S. A mitogen-activated protein kinase that senses nitrogen regulates conidial germination and growth in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot. Cell 2004, 3, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, G.; Romans, A.; Nguyen, C.K.; May, G.S. Novel mitogen-activated protein kinase MpkC of Aspergillus fumigatus is required for utilization of polyalcohol sugars. Eukaryot. Cell 2006, 5, 1934–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.X.; Xiao, C.L. Characterization of fludioxonil-resistant and pyrimethanil-resistant phenotypes of Penicillium expansum from apple. Phytopathology 2008, 98, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saccharomyces Genome Database. Available online: http://www.yeastgenome.org (accessed on 22 August 2015).

- Campbell, B.C.; Chan, K.L.; Kim, J.H. Chemosensitization as a means to augment commercial antifungal agents. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youngsaye, W.; Hartland, C.L.; Morgan, B.J.; Ting, A.; Nag, P.P.; Vincent, B.; Mosher, C.A.; Bittker, J.A.; Dandapani, S.; Palmer, M.; et al. ML212: A small-molecule probe for investigating fluconazole resistance mechanisms in Candida albicans. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 1501–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keniya, M.V.; Fleischer, E.; Klinger, A.; Cannon, R.D.; Monk, B.C. Inhibitors of the Candida albicans major facilitator superfamily transporter Mdr1p responsible for fluconazole resistance. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niimi, K.; Harding, D.R.; Parshot, R.; King, A.; Lun, D.J.; Decottignies, A.; Niimi, M.; Lin, S.; Cannon, R.D.; Goffeau, A.; et al. Chemosensitization of fluconazole resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and pathogenic fungi by a d-octapeptide derivative. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 1256–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freiesleben, S.H.; Jäger, A.K. Correlation between plant secondary metabolites and their antifungal mechanisms—A review. Med. Aromat. Plants 2014, 3, 154. [Google Scholar]

- Beekrum, S.; Govinden, R.; Padayachee, T.; Odhav, B. Naturally occurring phenols: A detoxification strategy for fumonisin B1. Food Addit. Contam. 2003, 20, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillen, F.; Evans, C.S. Anisaldehyde and veratraldehyde acting as redox cycling agents for H2O2 production by Pleurotus eryngii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 2811–2817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacob, C. A scent of therapy: Pharmacological implications of natural products containing redox-active sulfur atoms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006, 23, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, A.; Zhang, Y.; Muend, S.; Rao, R. Mechanism of antifungal activity of terpenoid phenols resembles calcium stress and inhibition of the TOR pathway. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 5062–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Everything Added to Food in the United States. Available online: http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/FoodAdditivesIngredients/ucm115326.htm (accessed on 7 August 2015).

- Bi, X.; Guo, N.; Jin, J.; Liu, J.; Feng, H.; Shi, J.; Xiang, H.; Wu, X.; Dong, J.; Hu, H.; et al. The global gene expression profile of the model fungus Saccharomyces cerevisiae induced by thymol. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 108, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, E.Y.; Cho, K.S.; Lee, H.S. Food protective effects of Periploca sepium oil and its active component against stored food mites. J. Food Prot. 2012, 75, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Yamashita, T.; Todo, A.; Nitoda, T.; Izumi, M.; Baba, N.; Nakajima, S. Repellent from traditional Chinese medicine, Periploca sepium Bunge. Z. Naturforsch. C 2007, 62, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi: Approved Standard–Second Edition. CLSI document M38-A2; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reinoso-Martín, C.; Schüller, C.; Schuetzer-Muehlbauer, M.; Kuchler, K. The yeast protein kinase C cell integrity pathway mediates tolerance to the antifungal drug caspofungin through activation of Slt2p mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Eukaryot. Cell 2003, 2, 1200–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senter, P.D.; Al-Abed, Y.; Metz, C.N.; Benigni, F.; Mitchell, R.A.; Chesney, J.; Han, J.; Gartner, C.G.; Nelson, S.D.; Todaro, G.J.; et al. Inhibition of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) tautomerase and biological activities by acetaminophen metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.; Silva, S.; van Voorst, F.; Aguiar, C.; Kielland-Brandt, M.C.; Brandt, A.; Lucas, C. Absence of Gup1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in defective cell wall composition, assembly, stability and morphology. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006, 6, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Hope, W. EUCAST technical note on the EUCAST definitive document EDef 7.2: Method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for yeasts EDef 7.2 (EUCAST-AFST). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, E246–E247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odds, F.C. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 52, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Monge, R.; Navarro-García, F.; Molero, G.; Diez-Orejas, R.; Gustin, M.; Pla, J.; Sánchez, M.; Nombela, C. Role of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1p in morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 3058–3068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- García-Rodriguez, L.J.; Durán, A.; Roncero, C. Calcofluor antifungal action depends on chitin and a functional high-osmolarity glycerol response (HOG) pathway: Evidence for a physiological role of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae HOG pathway under noninducing conditions. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 2428–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Ram, A.F.; Sheraton, J.; Klis, F.M.; Bussey, H. Regulation of cell wall beta-glucan assembly: PTC1 negatively affects PBS2 action in a pathway that includes modulation of EXG1 transcription. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1995, 248, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, M.H.; Silverman, S.J.; Gaughran, J.P.; Kirsch, D.R. Multiple copies of PBS2, MHP1 or LRE1 produce glucanase resistance and other cell wall effects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 1997, 13, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K.; Takano, Y.; Yoshimi, A.; Tanaka, C.; Kikuchi, T.; Okuno, T. Fungicide activity through activation of a fungal signalling pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 1785–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grintzalis, K.; Vernardis, S.I.; Klapa, M.I.; Georgiou, C.D. Role of oxidative stress in sclerotial differentiation and aflatoxin B1 biosynthesis in Aspergillus flavus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 5561–5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiante, V.; Jain, R.; Heinekamp, T.; Brakhage, A.A. The MpkA MAP kinase module regulates cell wall integrity signaling and pyomelanin formation in Aspergillus fumigatus. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2009, 46, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.; Valiante, V.; Remme, N.; Docimo, T.; Heinekamp, T.; Hertweck, C.; Gershenzon, J.; Haas, H.; Brakhage, A.A. The MAP kinase MpkA controls cell wall integrity, oxidative stress response, gliotoxin production and iron adaptation in Aspergillus fumigatus. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 82, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkman, T.W. Statistics to Use. Available online: http://www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/ (accessed on 12 August 2015).

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.H.; Chan, K.L.; Mahoney, N. Augmenting the Activity of Monoterpenoid Phenols against Fungal Pathogens Using 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde that Target Cell Wall Integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 26850-26870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms161125988

Kim JH, Chan KL, Mahoney N. Augmenting the Activity of Monoterpenoid Phenols against Fungal Pathogens Using 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde that Target Cell Wall Integrity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015; 16(11):26850-26870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms161125988

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jong H., Kathleen L. Chan, and Noreen Mahoney. 2015. "Augmenting the Activity of Monoterpenoid Phenols against Fungal Pathogens Using 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde that Target Cell Wall Integrity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16, no. 11: 26850-26870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms161125988

APA StyleKim, J. H., Chan, K. L., & Mahoney, N. (2015). Augmenting the Activity of Monoterpenoid Phenols against Fungal Pathogens Using 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde that Target Cell Wall Integrity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 16(11), 26850-26870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms161125988