Synthesis of Five Known Brassinosteroid Analogs from Hyodeoxycholic Acid and Their Activities as Plant-Growth Regulators

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemical Synthesis

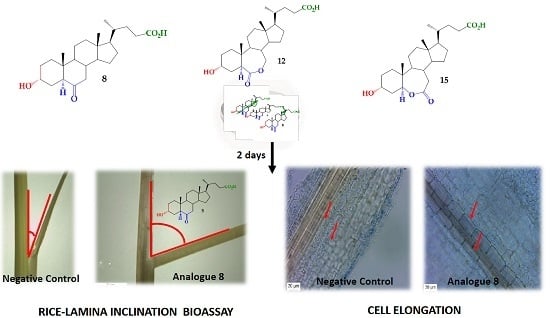

2.2. Bioactivity in the Rice Lamina Inclination Assay of Brassinosteroid Analogs

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

3.2. Synthesis

3.2.1. Methyl 2-en-6-oxo-5α-cholan-24-oate (9)

3.2.2. Methyl 2α, 3α-dihydroxy-6-oxo-5α-cholan-24-oate (6)

3.2.3. Methyl 3α-acetoxy-6-oxo-5α-cholan-24-oate (7)

3.2.4. Methyl 3α-acetoxy-6-oxo-7-oxa-5α-cholan-24-oate (10) and Methyl 3α-acetoxy-6-oxa-7-oxo-5α-cholan-24-oate (13)

3.2.5. Acid-3α-hydroxy-6-oxo-7-oxa-5α-cholan-24-oic (12)

3.2.6. Acid-3α-hydroxy-6-oxa-7-oxo-5α-cholan-24-oic (15)

3.3. Biological Activity: A Rice Lamina Inclination Assay

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| BRs | Brassinosteroids |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| PCC | Pyridinium ChloroChromate |

| DMAP | 4-Dimethylaminopyridine |

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| Tf2O | Trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride |

| m-CPBA | 3-Chloro or metha-chloroperoxybenzoic acid |

| DEPT-135 | Distortionless Enhancement by Polarization Transfer with flip angle of 135° |

| HSQC | Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence |

| HMBC | Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation |

References

- Bajguz, A. Brassinosteroids—Occurence and Chemical Structures in Plants. In Brassinosteroids: A Class of Plant Hormone; Hayat, S., Ahmad, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka, S. Natural Occurrence of Brassinosteroids in the Plant Kingdom. In Brassinosteroids: Steroidal Plant Hormones; Sakurai, A., Yokota, T., Clouse, S.D., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Tokyo, Japan, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marumo, S.; Hattori, H.; Abe, H.; Nonoyama, Y.; Munakata, K. Presence of Novel Plant Growth Regulators in Leaves of Distylium Racemosum Sieb et Zucc. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1968, 32, 528–529. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier, A.; Yokota, T.; Bishop, G.J.; Kamiya, Y. Biosynthesis of Hormones and Elicitor Molecules. In Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants; Buchanan, B.B., Gruissem, W., Jones, R.L., Eds.; American Society of Plant Physiologists: Rockville, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.W.; Mandava, N.; Worley, J.F.; Plimmer, J.R.; Smith, M.V. Brassins—A New Family of Plant Hormones from Rape Pollen. Nature 1970, 225, 1065–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grove, M.D.; Spencer, G.F.; Rohwedder, W.K.; Mandava, N.; Worley, J.F.; Warthen, J.D.; Steffens, G.L.; Flippenanderson, J.L.; Cook, J.C. Brassinolide, A Plant Growth-Promoting Steroid Isolated from Brassica-Napus Pollen. Nature 1979, 281, 216–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizek, D.T.; Mandava, N.B. Influence of Spectral Quality on the Growth-Response of Intact Bean-Plants to Brassinosteroid, A Growth-Promoting Steroidal Lactone. 2. Chlorophyll Content and Partitioning of Assimilate. Physiol. Plant. 1983, 57, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerana, R.; Bonetti, A.; Marre, M.T.; Romani, G.; Lado, P.; Marre, E. Effects of A Brassinosteroid on Growth and Electrogenic Proton Extrusion in Azuki Bean Epicotyls. Physiol. Plant. 1983, 59, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, G.; Marre, M.T.; Bonetti, A.; Cerana, R.; Lado, P.; Marre, E. Effects of A Brassinosteroid on Growth and Electrogenic Proton Extrusion in Maize Root Segments. Physiol. Plant. 1983, 59, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, P.; Wild, A. The Influence of Brassinosteroid on Growth and Parameters of Photosynthesis of Wheat and Mustard Plants. J. Plant Physiol. 1984, 116, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandava, N.B.; Sasse, J.M.; Yopp, J.H. Brassinolide, A Growth-Promoting Steroidal Lactone. 2. Activity in Selected Gibberellin and Cytokinin Bioassays. Physiol. Plant. 1981, 53, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilen, R.W.; Sacco, M.; Gusta, L.V.; Krishna, P. Effects of 24-Epibrassinolide on Freezing and Thermotolerance of Bromegrass (Bromus-Inermis) Cell-Cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1995, 95, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaubhadel, S.; Chaudhary, S.; Dobinson, K.F.; Krishna, P. Treatment with 24-epibrassinolide, a brassinosteroid, increases the basic thermotolerance of Brassica napus and tomato seedlings. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999, 40, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khripach, V.; Zhabinskii, V.; de Groot, A. Twenty years of brassinosteroids: Steroidal plant hormones warrant better crops for the XXI century. Ann. Bot. 2000, 86, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhini, B.V.; Anuradha, S.; Rao, S.S.R. Brassinosteroids—New class of plant hormone with potential to improve crop productivity. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Divi, U.K.; Krishna, P. Brassinosteroid: A biotechnological target for enhancing crop yield and stress tolerance. New Biotechnol. 2009, 26, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vriet, C.; Russinova, E.; Reuzeau, C. Boosting Crop Yields with Plant Steroids. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thompson, M.J.; Meudt, W.J.; Mandava, N.B.; Dutky, S.R.; Lusby, W.R.; Spaulding, D.W. Synthesis of Brassinosteroids and Relationship of Structure to Plant Growth-Promoting Effects. Steroids 1982, 39, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuto, S.; Yazawa, N.; Ikekawa, N.; Takematsu, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Koguchi, M. Structure Activity Relationship of Brassinosteroids. Phytochemistry 1983, 22, 2437–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuto, S.; Yazawa, N.; Ikekawa, N.; Morishita, T.; Abe, H. Synthesis of (24R)-28-Homobrassinolide Analogs and Structure Activity Relationships of Brassinosteroids in the Rice-Lamina Inclination Test. Phytochemistry 1983, 22, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosa, C.; Soca, L.; Terricabras, E.; Ferrer, J.C.; Alsina, A. New synthetic brassinosteroids: A 5 α-hydroxy-6-ketone analog with strong plant growth promoting activity. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 12337–12348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosa, C.; Capdevila, J.M.; Zamora, I. Brassinosteroids: A new way to define the structural requirements. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 2435–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Arteaga, M.A.; Martinez, C.P.; Manchado, F.C. Spirostanic analogues of castasterone. Steroids 2002, 67, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Avila, M.; de Dios-Bravo, G.; Mendez-Stivalet, J.M.; Rodriguez-Sotres, R.; Iglesias-Arteaga, M.A. Synthesis and biological activity of furostanic analogues of brassinosteroids bearing the 5 α-hydroxy-6-oxo moiety. Steroids 2007, 72, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosado-Abon, A.; de Dios-Bravo, G.; Rodriguez-Sotres, R.; Iglesias-Arteaga, M.A. Synthesis and plant growth promoting activity of polyhydroxylated ketones bearing the 5α-hydroxy-6-oxo moiety and cholestane side chain. Steroids 2012, 77, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, H.; Carvajal, R.; Olea, A.F.; Espinoza, L. Structural modifications of deoxycholic acid to obtain three known brassinosteroid analogues and full NMR spectroscopic characterization. Molecules 2016, 21, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Huang, L.; Tian, W.; Zhou, W. Methods for Construction of Sidechain of Brassinosteroids and Application to Syntheses of Brassinosteroids. In Structure and Chemistry (Part E); Rahman, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.S.; Tian, W.S. The Synthesis of Steroids Containing Structural Unit of A, B Ring of Brassinolide and Ecdysone from Hyodesoxycholic Acid. Acta Chim. Sin. 1984, 42, 1173–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.S.; Jiang, B.; Pan, X.F. Studies on Steroidal Plant-Growth Hormones. 8. the Regioselective Synthesis of Methyl 3-α-Hydroxy-7-Oxa-6-Oxo-B-Homo-5-α-Cholanate. Acta Chim. Sin. 1989, 47, 182–185. [Google Scholar]

- Iida, T.; Tamaru, T.; Chang, F.C.; Niwa, T.; Goto, J.; Nambara, T. Potential Bile-Acid Metabolites. 20. A New Synthetic Route to Stereoisomeric 3,6-Dihydroxy-5-α-Cholanoic and 6-Hydroxy-5-α-Cholanoic Acids. Steroids 1993, 58, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Jiang, B.; Shen, J. Synthesis of Cholesteric Lactones and Analogs as Plant Growth Regulators. Patent CN 1184113 A, 10 June 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.X.; Zheng, L.T.; Shi, J.J.; Gao, B.; Chen, Y.K.; Yang, H.C.; Chen, H.L.; Li, Y.C.; Zhen, X.C. Synthesis of 5 α-cholestan-6-one derivatives and their inhibitory activities of NO production in activated microglia: Discovery of a novel neuroinflammation inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 1222–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, K.; Marumo, S. Synthesis and Plant Growth-Promoting Activity of Brassinolide Analogs. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1981, 45, 2579–2585. [Google Scholar]

- Robaina, C.; Zullo, M.A.; Coll, F. Síntesis y Caracterización Espectroscópica de Análogos de Brasinoesteroides a partir de Ácido Cólico. Revista Cubana de Química XIII 2001, 2, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, D.G.; Leon, F.; Coll, F.; Davison, G.P. Novel 5β-hydroxyspirostan-6-ones ecdysteroid antagonists: Synthesis and biological testing. Steroids 2006, 71, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takatsuto, S.; Yazawa, N.; Ikekawa, N. Synthesis and Biological-Activity of Brassinolide Analogs, 26,27-Bisnorbrassinolide and Its 6-oxo Analog. Phytochemistry 1984, 23, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuto, S.; Ikekawa, N. Synthesis and Activity of Plant Growth-Promoting Steroids, (22R,23R,24S)-28-Homobrassinosteroids, with Modifications in Ring-A and Ring-B. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1984, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Arteaga, M.A.; Martinez, C.S.P.; Manchado, F.C. Synthesis and characterization of (25R)-2α,3α-epoxy-5α-spirostan-12,23-dione. Synth. Commun. 1999, 29, 1811–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuto, S.; Yazawa, N.; Ishiguro, M.; Morisaki, M.; Ikekawa, N. Stereoselective Synthesis of Plant Growth-Promoting Steroids, Brassinolide, Castasterone, Typhasterol, and Their 28-Nor Analogs. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1984, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.S.; Huang, L.F. Studies on Steroidal Plant-Growth Regulator. 25. Concise Stereoselective Construction of Side-Chain of Brassinosteroid from the Intact Side-Chain of Hyodeoxycholic Acid-Formal Syntheses of Brassinolide, 25-Methylbrassinolide, 26,27-Bisnorbrassinolide and Their Related-Compounds. Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 1837–1852. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.F.; Zhou, W.S. Studies on Steroidal Plant-Growth Regulators. 33. Novel Method for Construction of the Side-Chain of 23-Arylbrassinosteroids via Heck Arylation and Asymmetric Dihydroxylation as Key Steps. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1994, 24, 3579–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiguchi, T.; Machida, N.; Yamamoto, E. Dehydration of Alcohols Catalyzed by Copper(II) Sulfate Adsorbed on Silica-Gel. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 4565–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.R.; Haveli, S.D.; Kagan, H.B. A Mild-One Pot Method for Conversion of Various Steroidal Secondary Alcohols into the Corresponding Olefins. Synlett 2011, 12, 1709–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuto, S.; Ikekawa, N. Remote Substituent Effect on the Regioselectivity in the Baeyer-Villiger Oxidation of 5-α-Cholestan-6-One Derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 917–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, T.G. Stereoselective Synthesis of Brassinosteroids. In Stereoselective Synthesis (Part J); Rahman, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, B.; Schmidt, J.; Adam, G. Synthesis of 24-epiteasterone, 24-epityphasterol and their B-homo-6a-oxalactones from ergosterol. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 1997–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, E. Rate of Lamina Inclination in Excised Rice Leaves. Physiol. Plant. 1965, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeno, K.; Pharis, R.P. Brassinosteroid-Induced Bending of the Leaf Lamina of Dwarf Rice Seedlings—An Auxin-Mediated Phenomenon. Plant Cell Physiol. 1982, 23, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.A.; Centurion, O.M.T.; Gros, E.G.; Galagovsky, L.R. Synthesis and bioactivity evaluation of brassinosteroid analogs. Steroids 2000, 65, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takematsu, T.; Takenchi, Y.; Koguchi, M. New plant growth regulators, Brassinolide analogues: Their biological effects and application to agriculture and biomass production. Chem. Regul. Plants 1983, 18, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K.; Asano, T.; Marumo, S. Biological-Activity of Brassiosteroid Inhibitor Km-01 Produced by A Fungus Drechslera-Avenae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1995, 59, 1394–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, G.; Marquardt, V. Brassinosteroids. Phytochemistry 1986, 25, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, K.; Marumo, S.; Abe, H.; Morishita, T.; Nakamura, K.; Uchiyama, M.; Mori, K. A Rice Lamina Inclination Test—A Micro-Quantitative Bioassay for Brassinosteroids. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1984, 48, 719–726. [Google Scholar]

- Clouse, S.D.; Langford, M.; McMorris, T.C. A brassinosteroid-insensitive mutant in Arabidopsis thaliana exhibits multiple defects in growth and development. Plant Physiol. 1996, 111, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müssig, C.; Shin, G.-H.; Altmann, T. Brassinosteroids Promote Root Growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, D.H.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.L.; Hwang, I.; An, G. Regulation of brassinosteroid responses by phytochrome B in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, H.; Jin, Y.; Liu, W.; Fang, J.; Yin, Y.; Qian, Q.; Zhu, L.; Chu, C. Dwarf and low-tillering, a new member of the gras family, plays positive roles in brassinosteroid signaling in rice. Plant J. 2009, 58, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, H.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Gao, S.; Liu, L.; Yin, Y.; Jin, Y.; Qian, Q.; Chu, C. Brassinosteroid Regulates Cell Elongation by Modulating Gibberellin Metabolism in Rice. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 4376–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Fujioka, S.; Takatsuto, S.; Yokota, T.; Murofushi, N.; Sakurai, A. Biosynthesis of Brassinolide from Teasterone Via Typhasterol and Castasterone in Cultured-Cells of Catharanthus-Roseus. J. Plant Growth Regul. 1994, 13, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, H.; Morishita, T.; Uchiyama, M.; Takatsuto, S.; Ikekawa, N. A New Brassinolide-Related Steroid in the Leaves of Thea-Sinensis. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1984, 48, 2171–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, H.; Asakawa, S.; Ando, T.; Mouri, T.; Aburatani, M.; Takeuchi, T. Effect of Introducing A Lactone Group Into Typhasterol and Teasterone to Promote Rice Lamina Inclination. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1992, 56, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| C | 10 | 12 * | 13 | 15 * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33.69 | 34.04 | 31.74 | 32.40 |

| 2 | 27.84 | 28.90 | 27.37 | 28.51 |

| 3 | 68.48 | 65.49 | 69.43 | 66.95 |

| 4 | 29.79 | 33.39 | 32.86 | 36.57 |

| 5 | 42.64 | 42.88 | 79.53 | 81.59 |

| 6 | 176.11 | 179.68 | 174.73 | 178.28 |

| 7 | 70.47 | 71.75 | 38.02 | 38.79 |

| 8 | 39.43 | 40.79 | 34.70 | 36.36 |

| 9 | 58.43 | 59.49 | 57.91 | 59.09 |

| 10 | 36.18 | 37.25 | 39.58 | 40.88 |

| 11 | 22.15 | 23.26 | 22.09 | 23.27 |

| 12 | 39.64 | 41.01 | 39.52 | 40.97 |

| 13 | 42.66 | 43.82 | 42.61 | 43.87 |

| 14 | 55.81 | 57.12 | 56.00 | 57.46 |

| 15 | 25.17 | 28.83 | 25.15 | 28.51 |

| 16 | 24.80 | 25.76 | 24.75 | 26.32 |

| 17 | 51.52 | 52.54 | 55.37 | 56.54 |

| 18 | 11.79 | 12.21 | 11.67 | 12.15 |

| 19 | 14.58 | 14.93 | 11.48 | 11.83 |

| 20 | 35.32 | 36.62 | 35.18 | 36.62 |

| 21 | 18.14 | 18.63 | 18.04 | 18.62 |

| 22 | 30.81 | 31.95 | 30.66 | 31.97 |

| 23 | 31.03 | 32.15 | 30.90 | 32.12 |

| 24 | 174.59 | 178.09 | 174.39 | 178.20 |

| CH3O | 51.46 | - | 51.39 | - |

| CH3CO- | 170.32 | - | 170.02 | - |

| CH3CO- | 21.38 | - | 21.19 | - |

| BRs | Angle Degrees between Laminae and Sheaths (°) (± Standard Error) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (M) | |||

| Compounds | 1 × 10−6 | 1 × 10−7 | 1 × 10−8 |

| 5 | 11 ± 2.5 | 1 ± 0.0 | 0 ± 0.0 |

| 6 | 47 ± 4.7 | 29 ± 4.5 | 0 ± 1.0 |

| 8 | 49 ± 2.0 | 29 ± 6.3 | 7 ± 2.4 |

| 12 | 26 ± 2.5 | 26 ± 2.5 | 15 ± 0.0 |

| 15 | 23 ± 6.0 | 18 ± 8.7 | 10 ± 0.0 |

| Brassinolide (C+) | 64 ± 4.8 | 30 ± 4.1 | 28 ± 2.9 |

| Control (C−) | 20 ± 0 | ||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duran, M.I.; González, C.; Acosta, A.; Olea, A.F.; Díaz, K.; Espinoza, L. Synthesis of Five Known Brassinosteroid Analogs from Hyodeoxycholic Acid and Their Activities as Plant-Growth Regulators. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18030516

Duran MI, González C, Acosta A, Olea AF, Díaz K, Espinoza L. Synthesis of Five Known Brassinosteroid Analogs from Hyodeoxycholic Acid and Their Activities as Plant-Growth Regulators. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(3):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18030516

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuran, María Isabel, Cesar González, Alison Acosta, Andrés F. Olea, Katy Díaz, and Luis Espinoza. 2017. "Synthesis of Five Known Brassinosteroid Analogs from Hyodeoxycholic Acid and Their Activities as Plant-Growth Regulators" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 3: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18030516

APA StyleDuran, M. I., González, C., Acosta, A., Olea, A. F., Díaz, K., & Espinoza, L. (2017). Synthesis of Five Known Brassinosteroid Analogs from Hyodeoxycholic Acid and Their Activities as Plant-Growth Regulators. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(3), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18030516