Evidence Gaps in Clinical Trials of Pharmacologic Treatment for H1-Antihistamine-Refractory Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Systematic Review and Future Perspectives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Literature Search

2.2. Article Screening

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overview of Included Trials for H1-Antihistamine-Refractory CSU

3.2. Participant and Trial Characteristics

3.3. Trial Outcome Reporting

3.4. Evidence Gap across Included Trials

3.5. Summary of the Findings

3.6. Comparison with Other Studies

3.7. Strengths and Limitations

3.8. Implications for Conducting Clinical Trials, Future Research, and Conclusion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zuberbier, T.; Abdul Latiff, A.H.; Abuzakouk, M.; Aquilina, S.; Asero, R.; Baker, D.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Bangert, C.; Ben-Shoshan, M.; Bernstein, J.A.; et al. The international EAACI/GA2LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy 2022, 77, 734–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, J.; Ávila, G.; Keller, T.; Weller, K.; Lau, S.; Maurer, M.; Zuberbier, T.; Keil, T. Prevalence of chronic urticaria in children and adults across the globe: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Allergy 2020, 75, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maurer, M.; Weller, K.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Giménez-Arnau, A.; Bousquet, P.J.; Bousquet, J.; Canonica, G.W.; Church, M.K.; Godse, K.V.; Grattan, C.E.; et al. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA2LEN task force report. Allergy 2011, 66, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalo, M.; Gimenéz-Arnau, A.; Al-Ahmad, M.; Ben-Shoshan, M.; Bernstein, J.A.; Ensina, L.F.; Fomina, D.; Galvàn, C.A.; Godse, K.; Grattan, C.; et al. The global burden of chronic urticaria for the patient and society. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Khan, D.A.; Elieh Ali Komi, D.; Kaplan, A.P. Biologics for the Use in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: When and Which. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, M.; Sussman, G.; Gagnon, R.; Staubach, P.; Tanus, T.; Yang, W.H.; Lim, J.J.; Clarke, H.J.; Galanter, J.; Chinn, L.W.; et al. Fenebrutinib in H(1) antihistamine-refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria: A randomized phase 2 trial. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1961–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altrichter, S.; Staubach, P.; Pasha, M.; Singh, B.; Chang, A.T.; Bernstein, J.A.; Rasmussen, H.S.; Siebenhaar, F.; Maurer, M. An open-label, proof-of-concept study of lirentelimab for antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous and inducible urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 149, 1683–1690.e1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nochaiwong, S.; Chuamanochan, M.; Ruengorn, C.; Awiphan, R.; Tovanabutra, N.; Chiewchanvit, S. Evaluation of Pharmacologic Treatments for H1 Antihistamine-Refractory Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021, 157, 1316–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nochaiwong, S.; Chuamanochan, M.; Ruengorn, C.; Awiphan, R.; Tovanabutra, N.; Chiewchanvit, S.; Hutton, B.; Thavorn, K. Impact of Pharmacological Treatments for Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria with an Inadequate Response to H1-Antihistamines on Health-Related Quality of Life: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrow, A.; Xia, F.D.; Joyce, C.; Mostaghimi, A. Diversity in Dermatology Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017, 153, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diversifying clinical trials. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1779. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramamoorthy, A.; Pacanowski, M.A.; Bull, J.; Zhang, L. Racial/ethnic differences in drug disposition and response: Review of recently approved drugs. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 97, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.; Rosen, K.E.; Hsieh, H.J.; Wong, D.A.; Conner, E.; Kaplan, A.; Spector, S.; Maurer, M. A randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of single-dose omalizumab in patients with H1-antihistamine-refractory chronic idiopathic urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 567–573.e561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health; US Office of Budget and Management. Revisions to the Standards for the Classifications of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Available online: https://orwh.od.nih.gov/toolkit/other-relevant-federal-policies/OMB-standards (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maul, J.T.; Distler, M.; Kolios, A.; Maul, L.V.; Guillet, C.; Graf, N.; Imhof, L.; Lang, C.; Navarini, A.A.; Schmid-Grendelmeier, P. Canakinumab Lacks Efficacy in Treating Adult Patients with Moderate to Severe Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria in a Phase II Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Single-Center Study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 463–468.e463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leducq, S.; Samimi, M.; Bernier, C.; Soria, A.; Amsler, E.; Staumont-Sallé, D.; Gabison, G.; Chosidow, O.; Bénéton, N.; Bara, C.; et al. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate versus placebo as add-on therapy to H1 antihistamines for patients with difficult-to-treat chronic spontaneous urticaria: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pathania, Y.S.; Bishnoi, A.; Parsad, D.; Kumar, A.; Kumaran, M.S. Comparing azathioprine with cyclosporine in the treatment of antihistamine refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria: A randomized prospective active-controlled non-inferiority study. World Allergy Organ. J. 2019, 12, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, E.T.; Chichester, K.; Devine, K.; Sterba, P.M.; Wegner, C.; Vonakis, B.M.; Saini, S.S. Effects of an Oral CRTh2 Antagonist (AZD1981) on Eosinophil Activity and Symptoms in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 179, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Giménez-Arnau, A.M.; Sussman, G.; Metz, M.; Baker, D.R.; Bauer, A.; Bernstein, J.A.; Brehler, R.; Chu, C.Y.; Chung, W.H.; et al. Ligelizumab for Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Zakzuk, J.; Cardona, R. Evaluation of a Guidelines-Based Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 177–182.e171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jörg, L.; Pecaric-Petkovic, T.; Reichenbach, S.; Coslovsky, M.; Stalder, O.; Pichler, W.; Hausmann, O. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of the effect of omalizumab on basophils in chronic urticaria patients. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2018, 48, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metz, M.; Staubach, P.; Bauer, A.; Brehler, R.; Gericke, J.; Kangas, M.; Ashton-Chess, J.; Jarvis, P.; Georgiou, P.; Canvin, J.; et al. Clinical efficacy of omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria is associated with a reduction of FcεRI-positive cells in the skin. Theranostics 2017, 7, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hide, M.; Park, H.S.; Igarashi, A.; Ye, Y.M.; Kim, T.B.; Yagami, A.; Roh, J.; Lee, J.H.; Chinuki, Y.; Youn, S.W.; et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in Japanese and Korean patients with refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2017, 87, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boonpiyathad, T.; Sangasapaviliya, A. Hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of anti-histamine refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria, randomized single-blinded placebo-controlled trial and an open label comparison study. Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 49, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Staubach, P.; Metz, M.; Chapman-Rothe, N.; Sieder, C.; Bräutigam, M.; Canvin, J.; Maurer, M. Effect of omalizumab on angioedema in H1 -antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria patients: Results from X-ACT, a randomized controlled trial. Allergy 2016, 71, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M.; Cabanski, C.R.; Scheerens, H.; Samineni, D.; Bradley, M.S.; Cochran, C.; Staubach, P.; Metz, M.; Sussman, G.; Maurer, M. A randomized trial of quilizumab in adults with refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 1730–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saini, S.S.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Maurer, M.; Grob, J.J.; Bülbül Baskan, E.; Bradley, M.S.; Canvin, J.; Rahmaoui, A.; Georgiou, P.; Alpan, O.; et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria who remain symptomatic on H1 antihistamines: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, V.K.; Singh, S.; Ramam, M.; Kumawat, M.; Kumar, R. A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind pilot study of methotrexate in the treatment of H1 antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2014, 80, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Rosén, K.; Hsieh, H.J.; Saini, S.; Grattan, C.; Gimenéz-Arnau, A.; Agarwal, S.; Doyle, R.; Canvin, J.; Kaplan, A.; et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magerl, M.; Rother, M.; Bieber, T.; Biedermann, T.; Brasch, J.; Dominicus, R.; Hunzelmann, N.; Jakob, T.; Mahler, V.; Popp, G.; et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of safety and efficacy of miltefosine in antihistamine-resistant chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2013, 27, e363–e369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, A.; Ledford, D.; Ashby, M.; Canvin, J.; Zazzali, J.L.; Conner, E.; Veith, J.; Kamath, N.; Staubach, P.; Jakob, T.; et al. Omalizumab in patients with symptomatic chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria despite standard combination therapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vena, G.A.; Cassano, N.; Colombo, D.; Peruzzi, E.; Pigatto, P. Cyclosporine in chronic idiopathic urticaria: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 55, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagenstose, S.E.; Levin, L.; Bernstein, J.A. The addition of zafirlukast to cetirizine improves the treatment of chronic urticaria in patients with positive autologous serum skin test results. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grattan, C.E.; O’Donnell, B.F.; Francis, D.M.; Niimi, N.; Barlow, R.J.; Seed, P.T.; Kobza Black, A.; Greaves, M.W. Randomized double-blind study of cyclosporin in chronic ‘idiopathic’ urticaria. Br. J. Dermatol. 2000, 143, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, M.; Cooke, A.; Rogers, L.; Adams-Huet, B.; Khan, D.A. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of dapsone in antihistamine refractory chronic idiopathic urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2014, 2, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbagci, Z. The leukotriene receptor antagonist montelukast in the treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria: A single-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover clinical study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2002, 110, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.; Akhtar, S.; Zheng, C.; Kumaresan, V.; Nouri, K. Assessment of Changes in Diversity in Dermatology Clinical Trials Between 2010–2015 and 2015–2020: A Systematic Review. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHORD COUSIN Collaboration. The Cochrane Skin-Core Outcome Set Initiative (CS-COUSIN). Available online: http://cs-cousin.org/ (accessed on 17 July 2022).

- Dodd, S.; Clarke, M.; Becker, L.; Mavergames, C.; Fish, R.; Williamson, P.R. A taxonomy has been developed for outcomes in medical research to help improve knowledge discovery. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 96, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Detail |

|---|---|

| Participant characteristics |

|

| Trial characteristics |

|

| Outcomes of interest |

|

| Participant and Trial Characteristics | Number of Trials (%) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 23) | High-Income Countries (n = 18) † | Lower/Upper-Middle-Income Countries (n = 5) † | ||

| Total enrollment, participants; median (range, min–max) | 2480; 75 (20–340) | 2251; 83 (20–340) | 229; 35 (29–80) | 0.279 |

| <50 participants | 10 (43.5) | 7 (38.9) | 3 (60.0) | 0.563 |

| 50–100 participant | 8 (34.8) | 6 (33.3) | 2 (40.0) | |

| >100 participants | 5 (21.7) | 5 (27.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Reported mean age in year, grand mean ± S.D.; Median (range, min–max); missing data for one trial (4.3%) | 41.2 ± 3.4; 42.5 (32.2–45.7) | 41.3 ± 1.8; 42.7 (38.7–45.7) | 36.2 ± 4.7; 34.9 (32.2–42.8) | <0.001 |

| Age inclusion | ||||

| Only adults included | 16 (69.6) | 12 (66.7) | 4 (80.0) | 1.000 |

| Mixed children and adolescents/adults included | 7 (30.4) | 6 (33.3) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Reported % female, grand mean ± S.D.; Median (range, min– max); missing data for one trial (4.3%) | 64.8 ± 19.2; 69.6 (6.2–86.7) | 63.9 ± 20.6; 70.6 (6.2–86.7) | 68.5 ± 12.4; 65.0 (58.6–85.4) | 0.677 |

| Race/ethnicity reporting | ||||

| >80% white representation | 9 (39.1) | 9 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.108 |

| ≥20% non-white representation | 4 (17.4) | 3 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Neither race nor ethnicity reported | 10 (43.5) | 6 (33.3) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Type of refractory CSU | ||||

| Refractory to licensed-dose antihistamines | 9 (39.1) | 9 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.108 |

| Refractory to up-dosing antihistamines (two- to four-fold the licensed-dose) | 10 (43.5) | 6 (33.3) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Mixed/not specified | 4 (17.4) | 3 (16.7) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Duration of CSU in year, grand mean ± S.D.; Median (range, min–max); missing data for six trials (26.1%) | 5.0 ± 2.8; 5.1 (0.5–11.5) | 5.9 ± 2.4; 5.9 (2.4–11.5) | 2.4 ± 2.4; 1.7 (0.5–5.9) | 0.029 |

| Pharmacologic intervention class of studies: Specific intervention (no. of trials) ‡ | ||||

| Biologic drugs: Canakinumab (1), Ligelizumab (1), Omalizumab (10), Quilizumab (1) | 12 (52.2) | 11 (61.1) | 1 (20.0) | 0.214 |

| Immunosuppressive drugs: Azathioprine (1), Cyclosporine (4), Methotrexate (2) | 5 (21.7) | 3 (16.7) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Others: AZD1981—CRTh2 antagonist (1), Dapsone (1), Hydroxychloroquine (1), Miltefosine (1), Montelukast (1), Zafirlukast (1) | 6 (26.1) | 4 (22.2) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Year of publication | ||||

| Before 2015 | 10 (43.5) | 8 (44.4) | 2 (40.0) | 1.000 |

| 2015–2021 | 13 (56.5) | 10 (55.6) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Trial setting | ||||

| Monocentric | 8 (34.8) | 4 (22.2) | 4 (80.0) | 0.033 |

| Multicenter | 15 (65.2) | 14 (77.8) | 1 (20.0) | |

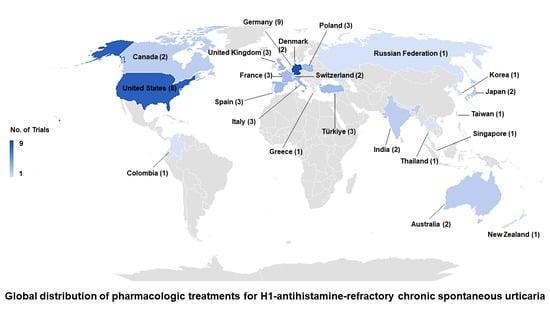

| Trial location: Country (no. of trials) | ||||

| North America/Europe: France (1), Germany (3), Italy (1), Switzerland (2), Türkiye (1), United Kingdom (1), United States (3) | 12 (52.2) | 11 (61.1) | 1 (20.0) | 0.001 |

| Others: Colombia (1), India (2), Thailand (1) | 4 (17.4) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (80.0) | |

| International (includes Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Poland, Russian Federation, Singapore, Spain, Taiwan, Türkiye, United Kingdom, United States) | 7 (30.4) | 7 (38.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Trial Design | ||||

| Parallel-group | 21 (91.3) | 17 (94.4) | 4 (80.0) | 0.395 |

| Crossover | 2 (8.7) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Control group in trial | ||||

| Placebo-controlled trial | 21 (91.3) | 18 (100.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0.040 |

| Active-controlled trial | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Trial Blinding | ||||

| Open-label/single-blind | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (60.0) | 0.006 |

| Double-blind | 20 (87.0) | 10 (100.0) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Arms in trial | ||||

| 2 | 18 (78.3) | 13 (72.2) | 5 (100.0) | 0.545 |

| ≥3 | 5 (21.7) | 5 (27.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Study treatment duration in week, grand mean ± S.D.; Median (range, min–max) | 12.0 ± 7.1; 12.0 (3.0–24.0) | 12.2 ± 7.9; 12.0 (3.0–24.0) | 11.6 ± 3.6; 12.0 (6.0–16.0) | 0.910 |

| <8 weeks | 8 (34.8) | 7 (38.9) | 1 (20.0) | 0.371 |

| 8–12 weeks | 7 (30.4) | 4 (22.2) | 3 (60.0) | |

| >12 weeks | 8 (34.8) | 7 (38.9) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Funding | ||||

| Industry sponsorship | 13 (56.5) | 13 (72.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.001 |

| Partial industry sponsorship | 3 (13.0) | 3 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Academic/government | 4 (17.4) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (40.0) | |

| None | 1 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Not reported | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Overall risk of bias | ||||

| Low | 13 (56.5) | 12 (66.7) | 1 (20.0) | 0.127 |

| Some concern | 10 (43.5) | 6 (33.3) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Outcomes | Number of Trials (%) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 23) | High-Income Countries (n = 18) † | Lower/Upper-Middle-Income Countries (n = 5) † | ||

| Treatment Efficacy (Specific Assessment Tool): Urticaria symptom | ||||

| UAS7 (scale, 0–42) | 16 (69.6) | 15 (83.3) | 1 (20.0) | 0.017 |

| Daily UAS (scale, 0–3), | 1 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | |

| USS (scale, 0–93), | 1 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | |

| VAS (scale, 0–100) | 1 (4.4) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Not reported | 4 (17.4) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Treatment Efficacy (Specific Assessment Tool): Pruritus severity | ||||

| UAS7-subscale itch (scale, 0–21) | 13 (56.5) | 13 (72.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.007 |

| Daily UAS-subscale itch (scale, 0–3) | 1 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | |

| VAS (scale, 0–100) | 1 (4.4) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Not reported | 8 (34.8) | 4 (22.2) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Treatment Efficacy (Specific Assessment Tool): Hive severity | ||||

| UAS7-subscale hive/wheal (scale, 0–21) | 12 (52.2) | 12 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.006 |

| Daily UAS-subscale hive/wheal (scale, 0–3) | 1 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Not reported | 10 (43.5) | 6 (33.3) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Safety Profile | ||||

| Unacceptability of treatment (all-cause study dropout) | 22 (95.6) | 18 (100.0) | 4 (80.0) | 0.217 |

| Occurrence of adverse events reported (participant with ≥1 adverse events) | 20 (87.0) | 17 (94.4) | 3 (60.0) | 0.107 |

| Occurrence of serious adverse events reported (participant with ≥1 serious adverse events) | 23 (100.0) | 18 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 1.000 |

| Patients-Reported Outcomes (Specific Assessment Tools) ‡ | ||||

| HRQOL: dermatology—specific measure (DLQI) | 10 (43.5) | 8 (44.4) | 2 (40.0) | 1.000 |

| HRQOL: chronic urticaria—specific measure (CU-Q2oL) | 4 (17.4) | 4 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.539 |

| HRQOL: angioedema—specific measure (AE-QoL) | 1 (4.4) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| HRQOL—generic measure (MOSS-SF12) | 1 (4.4) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Impact on sleep (UPDD-weekly sleep, VAS [scale, 0–100]) | 1 (4.4) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| General well-being (WHO-5 well-being index) | 5 (21.7) | 5 (27.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.545 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nochaiwong, S.; Chuamanochan, M.; Ruengorn, C.; Thavorn, K. Evidence Gaps in Clinical Trials of Pharmacologic Treatment for H1-Antihistamine-Refractory Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Systematic Review and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15101246

Nochaiwong S, Chuamanochan M, Ruengorn C, Thavorn K. Evidence Gaps in Clinical Trials of Pharmacologic Treatment for H1-Antihistamine-Refractory Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Systematic Review and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceuticals. 2022; 15(10):1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15101246

Chicago/Turabian StyleNochaiwong, Surapon, Mati Chuamanochan, Chidchanok Ruengorn, and Kednapa Thavorn. 2022. "Evidence Gaps in Clinical Trials of Pharmacologic Treatment for H1-Antihistamine-Refractory Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Systematic Review and Future Perspectives" Pharmaceuticals 15, no. 10: 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15101246

APA StyleNochaiwong, S., Chuamanochan, M., Ruengorn, C., & Thavorn, K. (2022). Evidence Gaps in Clinical Trials of Pharmacologic Treatment for H1-Antihistamine-Refractory Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria: A Systematic Review and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceuticals, 15(10), 1246. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15101246