Chemoecological Screening Reveals High Bioactivity in Diverse Culturable Portuguese Marine Cyanobacteria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Diversity

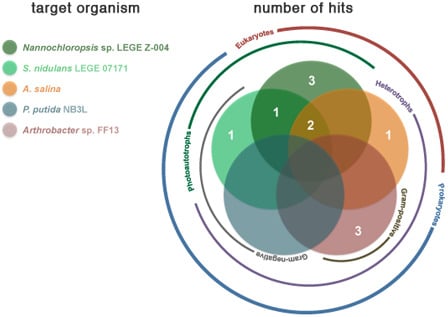

2.2. Bioactivity

| Taxon | Strain Code | Origin a | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romeria sp. | LEGE 06013 | Foz do Arelho (D) | [13] |  |

| Pseudanabaena sp. | LEGE 06116 | Martinhal (E) | [13] | |

| Leptolyngbya sp. | LEGE 06133 | Moledo (A) | b | |

| Pseudanabaena cf. frigida | LEGE 06144 | Burgau (F) | [13] | |

| Pseudanabaenaceae cyanobacterium | LEGE 06148 | Moledo (A) | b | |

| Nodosilinea nodulosa * | LEGE 06152 | Lavadores (B) | [13] | |

| Nodosilinea nodulosa | LEGE 06191 | Burgau (F) | b | |

| cf. Gloeocapsa sp. | LEGE 06192 | Burgau (F) | b | |

| Leptolyngbya saxicola | LEGE 07132 | Luz (G) | [13] | |

| Leptolyngbyamycoidea | LEGE 07157 | Lavadores (B) | [13] | |

| Schizothrix aff. septentrionalis | LEGE 07164 | Moledo (A) | [13] | |

| Pseudanabaena cf. curta | LEGE 07169 | Aguda (C) | [13] | |

| Calothrix sp. | LEGE 07177 | Martinhal (E) | [13] |

| Strain | Active Fractions in each bioassay a (Lowest Concentration Observed) [Lethality or Inhibition, %] b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemia salina | Arthrobacter sp. FF13 | Pseudomonas putida NB3L | Nannochloropsis sp. LEGE Z-004 | Synechococcus nidulans LEGE 07171 | |

| LEGE 06013 | B (100 μg mL−1) [25.2 ± 7.3] | - | - | A; B (100 μg mL−1) [A: 100 ± 38.9] [B: 100 ± 12.1] * | A (100 μg mL−1) [54.9 ± 4.2] |

| LEGE 06116 | - | - | - | - | - |

| LEGE 06133 | - | A (100 μg mL−1) [50.3 ± 11.9] | - | - | |

| LEGE 06144 | - | - | - | B (100 μg mL−1) [88.7 ± 14.3] | B (100 μg mL−1) [78.8 ± 13.3] |

| LEGE 06148 | - | - | - | A (100 μg mL−1); B (10 μg mL−1) [A: 66.4 ± 18.4] [B: 93.8 ± 3.9] | - |

| LEGE 06152 | - | B (100 μg mL−1) [70.5 ± 24.5] | - | - | - |

| LEGE 06191 | - | - | - | - | - |

| LEGE 06192 | - | - | - | - | A (100 μg mL−1) [67.5 ± 11.9] |

| LEGE 07132 | B (100 μg mL−1) [45.9 ± 11.1] | - | - | - | - |

| LEGE 07157 | - | - | - | B (100 μg mL−1) [100 ± 9.8 ] * | - |

| LEGE 07164 | - | - | - | B; C (10 μg mL−1) [B: 36.5 ± 9.1] [C: 19.5 ± 7.6] | - |

| LEGE 07169 | B (100 μg mL−1) [54.0 ± 10.9] | - | - | B; C (10 μg mL−1) [B: 38.0 ± 6.0] [C: 43.5 ± 8.1] | C (100 μg mL−1) [92.7 ± 1.3] |

| LEGE 07177 | - | A (100 μg mL−1) [70.9 ± 24.9] | - | - | - |

2.3. Dereplication

2.4. Bioassay-Guided Purification of the Constituents of Romeria sp. LEGE 06013

3. Discussion

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Cyanobacterial Cultures

4.2. 16S rRNA Gene Amplification, Cloning and Sequencing

4.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

4.4. Extraction and Fractionation

4.5. Bioassays

- (a)

- Artemia salina (brine shrimp) toxicity assay. The assay was conducted as previously reported [35]. Mortality rates were determined at 24 and 48 h following exposure and a 0.4 mg mL−1 potassium dichromate solution in DMSO was used as a positive control (4 μg mL−1 final concentration in each well).

- (b)

- Arthrobacter sp. FF13. This strain was isolated from Fucus spiralis in Porto, Portugal (41°09′N; 8°40′W). Liquid cultures in M607 medium [63] were grown in the dark at 25 °C with shaking to exponential phase and diluted to 0.1 OD (750 nm) in each of the assay wells in M607 medium. A mixture of penicillin (50 units mL−1), streptomycin (50 μg mL−1) and neomycin (100 μg mL−1) was used as a positive control (values are final concentrations). Plates were incubated under the conditions described for the batch cultures. Growth of the treatments and controls was evaluated by OD measurements at 750 nm after 48 h.

- (c)

- Pseudomonas putida NB3L was isolated from a sponge belonging to the “Cliona viridis complex” at 4 to 5 m depth in Parque Natural da Berlenga, Portugal. The assay was performed as described above for Arthrobacter sp. FF13, however, in this case, a simple medium of filtered (0.22 μm) seawater supplemented with peptone (5 g L−1) and yeast extract (1 g L−1) was used.

- (d)

- A marine Nannochloropsis sp. strain (LEGE Z-004) was used to study the phycotoxic or potential allelopathic properties of the extracts. The microalgae were grown in batch culture in Z8 medium supplemented with 25 g L−1 NaCl under the same light and temperature conditions as described above for the cyanobacterial strains. The strain was inoculated to ~0.1 OD (750 nm) in each of the microplate wells. Potassium dichromate served as positive control as described above for the Artemia salina bioassay. The 96-well microplate was incubated under the same conditions as the batch cultures and OD at 750 nm was used to measure growth after 72 h.

- (e)

- The marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus nidulans LEGE 07171 was used as a photosynthetic prokaryotic target from a ubiquitous genus. The bioassay employing this strain was performed as described for Nannochloropsis sp. LEGE Z-004, however, the positive control was the antibiotic mixture mentioned above for the other prokaryotic targets. Growth was estimated by OD measurements (750 nm) after 120 h.

4.6. LC-MS Analyszzes and Dereplication

4.7. Bioassay-Guided Purification of the Constituents of Romeria sp. LEGE 06013

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Nunnery, J.K.; Mevers, E.; Gerwick, W.H. Biologically active secondary metabolites from marine cyanobacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 787–793. [Google Scholar]

- Engene, N.; Rottacker, E.C.; Kaštovský, J.; Byrum, T.; Choi, H.; Ellisman, M.H.; Komárek, J.; Gerwick, W.H. Moorea producta gen. nov., sp. nov. and Moorea bouillonii comb. nov., tropical marine cyanobacteria rich in bioactive secondary metabolites. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 62, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L.T. Bioactive natural products from marine cyanobacteria for drug discovery. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 954–979. [Google Scholar]

- Engene, N.; Choi, H.; Esquenazi, E.; Rottacker, E.C.; Ellisman, M.H.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Gerwick, W.H. Underestimated biodiversity as a major explanation for the perceived rich secondary metabolite capacity of the cyanobacterial genus Lyngbya. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 1601–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolser, R.C.; Hay, M.E. Are tropical plants better defended? Palatability and defenses of temperate vs. tropical seaweeds. Ecology 1996, 77, 2269–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taton, A.; Grubisic, S.; Brambilla, E.; de Wit, R.; Wilmotte, A. Cyanobacterial diversity in natural and artificial microbial mats of Lake Fryxell (McMurdo dry valleys, Antarctica): A morphological and molecular approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 5157–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, B.A.; Potts, M. The Ecology of Cyanobacteria: Their Diversity in Time and Space; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Papendorf, O.; König, G.M.; Wright, A.D. Hierridin B and 2,4-dimethoxy-6-heptadecyl-phenol, secondary metabolites from the cyanobacterium Phormidium ectocarpi with antiplasmodial activity. Phytochemistry 1998, 49, 2383–2386. [Google Scholar]

- Sivonen, K.; Kononen, K.; Carmichael, W.W.; Dahlem, A.M.; Rinehart, K.L.; Kiviranta, J.; Niemela, S.I. Occurrence of the hepatotoxic cyanobacterium Nodularia spumigena in the Baltic Sea and structure of the toxin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1989, 55, 1990–1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.Y.; Luesch, H. Largazole: From discovery to broad-spectrum therapy. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012, 29, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.R.; Kale, A.J.; Fenley, A.T.; Byrum, T.; Debonsi, H.M.; Gilson, M.K.; Valeriote, F.A.; Moore, B.S.; Gerwick, W.H. The carmaphycins: New proteasome inhibitors exhibiting an α,β-epoxyketone warhead from a marine cyanobacterium. ChemBioChem 2012, 13, 810–817. [Google Scholar]

- Leão, P.N.; Engene, N.; Antunes, A.; Gerwick, W.H.; Vasconcelos, V. The chemical ecology of cyanobacteria. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012, 29, 372–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A.; Ramos, V.; Seabra, R.; Santos, A.; Santos, C.L.; Lopo, M.; Ferreira, S.; Martins, A.; Mota, R.; Frazão, B.; et al. Culture-dependent characterization of cyanobacterial diversity in the intertidal zones of the Portuguese coast: A polyphasic study. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 35, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Abed, R.M.M.; Garcia-Pichel, F.; Hernandez-Marine, M. Polyphasic characterization of benthic, moderately halophilic, moderately thermophilic cyanobacteria with very thin trichomes and the proposal of Halomicronema excentricum gen. nov., sp. nov. Arch. Microbiol. 2002, 177, 361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Rippka, R.; Deruelles, J.; Waterbury, J.B. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1979, 111, 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, D.; Yokota, A.; Sugiyama, J. Detection of seven major evolutionary lineages in cyanobacteria based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis with new sequences of five marine Synechococcus strains. J. Mol. Evol. 1999, 48, 723–739. [Google Scholar]

- Castenholz, R.W.; Phylum, B.X. Cyanobacteria: Oxygenic Photosynthetic Bacteria. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology; Boone, D.R., Castenholz, R.W., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 473–553. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Choi, J.S.; Yoo, J.S.; Park, Y.M.; Kim, M.S. Structural identification of glycerolipid molecular species isolated from cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 using fast atom bombardment tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 1999, 267, 260–270. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, N.; Morimoto, T.; Imamura, H.; Ueda, T.; Nagai, S.; Sakakibara, J.; Yamada, N. Studies on glycolipids. III. Glyceroglycolipids from an axenically cultured cyanobacterium, Phormidium tenue. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 1991, 39, 2277–2281. [Google Scholar]

- Reshef, V.; Mizrachi, F.; Maretzki, T.; Silberstein, C.; Loya, S.; Hizi, A.; Carmeli, S. New acylated sulfoglycolipids and digalactolipids and related known glycolipids from cyanobacteria with a potential to inhibit the reverse transcriptase of HIV-1. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Leão, P.N.; Vasconcelos, M.T.S.D.; Vasconcelos, V.M. Allelopathy in freshwater cyanobacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 35, 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, J.I.; Minambres, B.; Garcia, J.L.; Diaz, E. Genomic analysis of the aromatic catabolic pathways from Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 4, 824–841. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Pichel, F.; Lopez-Cortes, A.; Nubel, U. Phylogenetic and morphological diversity of cyanobacteria in soil desert crusts from the Colorado Plateau. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casamatta, D.A.; Johansen, J.R.; Vis, M.L.; Broadwater, S.T. Molecular and morphological characterization of ten polar and near-polar strains within the Oscillatoriales (Cyanobacteria). J. Phycol. 2005, 41, 421–438. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, T.; Watanabe, M.M.; Sugiyama, J.; Yokota, A. Evidence for polyphyletic origin of the members of the orders of Oscillatoriales and Pleurocapsales as determined by 16S rDNA analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001, 201, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fewer, D.; Friedl, T.; Budel, B. Chroococcidiopsis and heterocyst-differentiating cyanobacteria are each other’s closest living relatives. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2002, 23, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gugger, M.F.; Hoffmann, L. Polyphyly of true branching cyanobacteria (Stigonematales). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, J.; Palinska, K.A. Genotypic and phenotypic diversity of cyanobacteria assigned to the genus Phormidium (Oscillatoriales) from different habitats and geographical sites. Arch. Microbiol. 2007, 187, 397–413. [Google Scholar]

- Bohunicka, M.; Johansen, J.R.; Fucikova, K. Tapinothrix clintonii sp. nov. (Pseudanabaenaceae, Cyanobacteria), a new species at the nexus of five genera. Fottea 2011, 11, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Siegesmund, M.A.; Johansen, J.R.; Karsten, U.; Friedl, T. Coleofasciculus gen. nov. (Cyanobacteria): Morphological and molecular criteria for revision of the genus Microcoleus Gomont. J. Phycol. 2008, 44, 1572–1585. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.K.; Brand, J. Leptolyngbya nodulosa sp. nov. (Oscillatoriaceae), a subtropical marine cyanobacterium that produces a unique multicellular structure. Phycologia 2007, 46, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkerson, R.B.; Johansen, J.R.; Kovacik, L.; Brand, J.; Kastovsky, J.; Casamatta, D.A. A unique Pseudanabaenalean (Cyanobacteria) genus Nodosilinea gen. nov. based on morphological and molecular data. J. Phycol. 2011, 47, 1397–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leikoski, N.; Fewer, D.P.; Jokela, J.; Alakoski, P.; Wahlsten, M.; Sivonen, K. Analysis of an inactive cyanobactin biosynthetic gene cluster leads to discovery of new natural products from strains of the genus Microcystis. PLoS One 2012, 7, e43002. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, S.A.; Mihali, T.K.; Neilan, B.A. Extraordinary conservation, gene loss and positive selection in the evolution of an ancient neurotoxin. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, V.R.; Fernandez, N.; Martins, R.F.; Vasconcelos, V. Primary screening of the bioactivity of brackishwater cyanobacteria: Toxicity of crude extracts to Artemia salina larvae and Paracentrotus lividus embryos. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 471–482. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, R.; Fernandez, N.; Beiras, R.; Vasconcelos, V. Toxicity assessment of crude and partially purified extracts of marine Synechocystis and Synechococcus cyanobacterial strains in marine invertebrates. Toxicon 2007, 50, 791–799. [Google Scholar]

- Herfindal, L.; Oftedal, L.; Selheim, F.; Wahlsten, M.; Sivonen, K.; Doskeland, S.O. A high proportion of Baltic Sea benthic cyanobacterial isolates contain apoptogens able to induce rapid death of isolated rat hepatocytes. Toxicon 2005, 46, 252–260. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, B.; Liebezeit, G. Chemical screening for bioactive substances in culture media of microalgae and cyanobacteria from marine and brackish water habitats: First results. Pharm. Biol. 2006, 44, 544–549. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes, M.T.; Aguiar, R.; Pires, H.O. A nearshore wave energy atlas for Portugal. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2005, 127, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta-Almeida, M.; Dubert, J. The structure of tides in the Western Iberian region. Cont. Shelf Res. 2006, 26, 385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Banik, J.J.; Brady, S.F. Recent application of metagenomic approaches toward the discovery of antimicrobials and other bioactive small molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2010, 13, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacheva, G.; Gigova, L.; Ivanova, N.; Iliev, I.; Toshkova, R.; Gardeva, E.; Kussovski, V.; Najdenski, H. Suboptimal growth temperatures enhance the biological activity of cultured cyanobacterium Gloeocapsa sp. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Izaguirre, G.; Taylor, W.D. A Pseudanabaena species from Castaic Lake, California, that produces 2-methylisoborneol. Water Res. 1998, 32, 1673–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantar, M.; Sekar, R.; Richardson, L.L. Cyanotoxins from black band disease of corals and from other Coral Reef environments. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 58, 856–864. [Google Scholar]

- Tidgewell, K.; Clark, B.R.; Gerwick, W.H. The Natural Products Chemistry of Cyanobacteria. In Comprehensive Natural Products II Chemistry and Biology; Mander, L., Lui, H.-W., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 141–188. [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan, G.G.; Yoshida, W.Y.; Moore, R.E.; Nagle, D.G.; Park, P.U.; Biggs, J.; Paul, V.J.; Mooberry, S.L.; Corbett, T.H.; Valeriote, F.A. Isolation, structure determination, and biological activity of dolastatin 12 and lyngbyastatin I from Lyngbya majuscula/Schizothrix calcicola cyanobacterial assemblages. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Sitachitta, N.; Williamson, R.T.; Gerwick, W.H. Yanucamides A and B, two new depsipeptides from an assemblage of the marine cyanobacteria Lyngbya majuscula and Schizothrix species. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogle, L.M.; Gerwick, W.H. Somocystinamide A, a novel cytotoxic disulfide dimer from a Fijian marine cyanobacterial mixed assemblage. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 1095–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, T.; Mimura, T.; Harimaya, K.; Yano, H.; Arimoto, T.; Masada, Y.; Inoue, T. Odorous metabolite of blue green algae—Schizothrix muelleri Nageli collected in Southern Basin of Lake Biwa—Identification of geosmin. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 1973, 21, 2342–2343. [Google Scholar]

- Pergament, I.; Carmeli, S. Schizotrin A—A novel antimicrobial cyclic peptide from a cyanobacterium. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 8473–8476. [Google Scholar]

- Linington, R.G.; Clark, B.R.; Trimble, E.E.; Almanza, A.; Urena, L.D.; Kyle, D.E.; Gerwick, W.H. Antimalarial peptides from marine cyanobacteria: Isolation and structural elucidation of Gallinamide A. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Cyanoprokaryota, Part 1: Chroococcales. In Süsswasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Ettl, H., Gärtner, G., Heynig, H., Mollenhauer, D., Eds.; Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; Volume 19/1, p. 548. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Cyanoprokaryota, Part 2: Oscillatoriales. In Süsswasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Büdel, B., Gärtner G. Krienitz, L., Schagerl, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Munich, Germany, 2005; Volume 19/2, p. 759. [Google Scholar]

- Kotai, J. Instructions for the Preparation of Modified Nutrient Solution Z8 for Algae; Publication B-11/69; Norwegian Institute for Water Research: Blindern, Oslo, Norway, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Rippka, R. Isolation and Purification of Cyanobacteria. In Methods Enzymol; Packer, L., Glazer, A.N., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1988; Volume 167, pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nübel, U.; GarciaPichel, F.; Muyzer, G. PCR primers to amplify 16S rRNA genes from cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 3327–3332. [Google Scholar]

- Neilan, B.A.; Jacobs, D.; DelDot, T.; Blackall, L.L.; Hawkins, P.R.; Cox, P.T.; Goodman, A.E. rRNA sequences and evolutionary relationships among toxic and nontoxic cyanobacteria of the genus Microcystis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1997, 47, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Peterson, D.; Peterson, N.; Stecher, G.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 2731–2739. [Google Scholar]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: More models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 772–772. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 754–755. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, H.A.; Strimmer, K.; Vingron, M.; von Haeseler, A. TREE-PUZZLE: Maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis using quartets and parallel computing. Bioinformatics 2002, 18, 502–504. [Google Scholar]

- Stover, B.C.; Muller, K.F. TreeGraph 2: Combining and visualizing evidence from different phylogenetic analyses. BMC Bioinforma. 2010, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lage, O.M.; Bondoso, J. Planctomycetes diversity associated with macroalgae. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 78, 366–375. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Leão, P.N.; Ramos, V.; Gonçalves, P.B.; Viana, F.; Lage, O.M.; Gerwick, W.H.; Vasconcelos, V.M. Chemoecological Screening Reveals High Bioactivity in Diverse Culturable Portuguese Marine Cyanobacteria. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 1316-1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11041316

Leão PN, Ramos V, Gonçalves PB, Viana F, Lage OM, Gerwick WH, Vasconcelos VM. Chemoecological Screening Reveals High Bioactivity in Diverse Culturable Portuguese Marine Cyanobacteria. Marine Drugs. 2013; 11(4):1316-1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11041316

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeão, Pedro N., Vitor Ramos, Patrício B. Gonçalves, Flávia Viana, Olga M. Lage, William H. Gerwick, and Vitor M. Vasconcelos. 2013. "Chemoecological Screening Reveals High Bioactivity in Diverse Culturable Portuguese Marine Cyanobacteria" Marine Drugs 11, no. 4: 1316-1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11041316

APA StyleLeão, P. N., Ramos, V., Gonçalves, P. B., Viana, F., Lage, O. M., Gerwick, W. H., & Vasconcelos, V. M. (2013). Chemoecological Screening Reveals High Bioactivity in Diverse Culturable Portuguese Marine Cyanobacteria. Marine Drugs, 11(4), 1316-1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/md11041316