Social Isolation in Older Adults: A Qualitative Study on the Social Dimensions of Group Outdoor Health Walks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Risks of Social Isolation for Older Adults

1.2. Interventions to Mitigate Social Isolation in Older Adults

1.3. Group Outdoor Health Walks

1.4. Challenges of Measuring the Social Dimensions in Nature-Health Research

1.5. Conceptualising Social Dimensions of GOHWs and Their Effect on Health-Negotiating Cross-Disciplinary Discourse

1.5.1. Social Support

1.5.2. Social Capital

1.5.3. Social Cohesion

1.5.4. Group Cohesion

1.5.5. Social Wellbeing

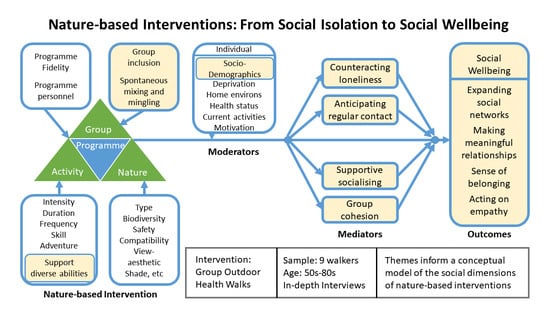

1.6. Conceptual Model for Investigating NBIs

1.7. Study Focus

- How do individuals taking part in an NBI for the promotion of physical activity articulate the social processes and outcomes they experience?

- What are the salient dimensions of the social environment related to outdoor group health walks?

- How can the conceptual model of NBIs for health be adapted to illustrate the social dimensions for individual social wellbeing?

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Recruitment Process

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Programmatic Elements Fostering Engagement

Particularly people who are getting on in life sometimes have difficulty fitting in because they’re older, because they feel ‘I don’t really know these people’, and it’s very important for their wellbeing if they’re in a group with people of similar problems, … I don’t think some of the folk have done an awful lot of walking and I think they need a bit of assistance. … if they felt that they couldn’t do the full walk then there was the freedom to stop and come back, and somebody would go with you. So, there was an element of security, I felt, as far as they were concerned that somebody was going to look after them and accompany them… (P8)

There was a couple of the golden oldies of the village in there, so I recognised their faces, so that was good. There was [the walk leader’s] beaming smile and, ‘Hello, come in!’. … [And] everybody else in the group made me feel really welcome the first day. (P1)

A few times, I did go with the group, but I’d used to have to have a seat and they’d go, ‘Bye’ and I’d sit there and wait for them but with [the new walk leader], I didn’t do that. … He made you want to walk. I mean, I remember my first day with him and I was at the very back, he was at the very back with me. … he said, ‘No, you’re not walking on your own’, and he was just so good. (P6 and P7)

3.2. Spontaneous Mixing and Mingling

I think it’s just strolling along on the walk… the group at the front… they were all … talking to each other. I was at the back…and we are talking… about this, that and the other, so there is a bit of social intercourse there. (P2)

We’ve all got our own individual [activity tracker] that we look at, and because we’re doing it individually, we are discussing it as a group as well. Some people would turn around and say, ‘Well, I’ve done more steps than you.’ It didn’t become a competition or anything like that… It was a recognition that you got by having a tracker. (P3)

It’s just the being in a group rather than walking [by] yourself or with a friend… you don’t compare [the walking group] to coffee mornings because [they are] a bit static, where you go for coffee somewhere so you feel you’ve got to invite them back. [Instead] you can go for a walk with the group and it’s a casual friendship getting to know people, which appeals to me. (P9)

3.3. Evolving Social Experiences

3.3.1. Counteracting Loneliness

I would reckon that the social implications of anything you do like… walking for health, the benefit is a 60/40 in favour of the social side. It might be 70/30… it’s certainly, in my opinion, more important than the actual activity itself. I thought… this could be of some use to people … because a lot of people are… lonely. (P8)

My dad passed away so I was on my own. I’m not married and I don’t have children. I was kind of lost after dad passed away. … and I was like, ‘What do I do with my life? What is this?’, and my mood was dropping a bit. I don’t know if it was the grieving process or what. [The walking group provided] company for me because I’m on my own, I’m in the house. … if you don’t see the neighbours then you could go all day without anybody. (P1)

I’ve been a hillwalker for 70 years. … I like walking and being out. … Living alone, I thought, ‘Well, this is good because other people with similar sort of things might join up…’. (P8)

3.3.2. Anticipating Regular Contact

3.3.3. Supportive Socialising

When you’re out walking with people and the other men, the camaraderie of everybody and socially, you forget all about that. You just get on with it. … Yes, you don’t sort of dwell on yourself. You get out there and do it which is good. (P4)

P6: If we did [the walk] on our own, we probably would have turned back and finished it earlier. This is where the group…P7: The group comes in, yes. I would have turned back, I would have definitely turned back but because there were other people there, I was … encouraged. (P6 and P7)

I think it was getting everybody together and realising that we can go further and that it’s enjoyable together. So, there is the motivation, there is the social side, and there is the improvement in your health and ability. Thinking back to the beginning of it, and then as we went through, I’m pretty sure that the majority of people would be comfortable … [and] confident in their ability to go further. (P3)

3.3.4. Emerging Group Cohesion

[Some walkers] thought we should patronise different [cafés] … We did try that, but there was a problem in that if you missed a week, where are we going to meet? Eventually, we got everybody to agree that we should stay at one location so that everybody knows, ‘This is where we meet, if at all possible’. (P3)

We’ve had discussions … and there has been a suggestion that we pick two walks each … and perhaps prepare beforehand… I think we’re probably going to settle for thinking about two walks each, two within the village and two out with the village. (P3)

There’s been a bit of reluctance sometimes within the group to discuss things and hear different people’s opinion … People tend to go off and speak quietly to each other … about the walks … about the group and what we’re aiming for … but not bringing [this to the group] … [to] hear different people’s ideas. (P9)

I like to think that if we’d just carry on the way we are if somebody comes along that doesn’t fit in for whatever reason, that they’re not caring or they’re more dictatorial, it would just sort itself out. (P3)

3.4. Achieving Individual Social Wellbeing

3.4.1. Expanding Social Networks

That there would be more village people involved in this; but local people indigenous to [the area], they’re sometimes reluctant. I think if you look at the people who are on this, you will find that it’s mainly incomers… [of less than seven years]. (P8)

People know the houses as well. You walk past the houses and, ‘Oh, such and such lives there’, and you wouldn’t know that before. Somebody would say, ‘Oh, I went to school there’, and it was the old school. … You get little stories about what happened. (P6 and P7)

3.4.2. Making Meaningful Relationships

Like this … old guy… I’ve always thought of [him] as quiet and he still is quiet but some of the comments he used to make … He was so tongue-in-cheek and he’s so funny. Now, coming into the shop or just meeting him in the street, you wouldn’t have known that but for sitting talking to him … He’s a font of all knowledge. (P6 and P7)

I’ve made friendships. A good laugh … you realise that it’s good to mix and not sit and dwell on things [like losses]. (P1)

While I knew some of the people on it, it has increased our friendship and camaraderie, I would say. I can be out … and I go past their house and there are waves … or if they’re out, we stop and have a chat for a few minutes and it’ll be, ‘I’ll see you Friday’. That actually makes you feel better in yourself. (P2)

You probably know them as your neighbour and just wave, but now you know them a bit more personally than you knew before and you have more empathy towards them as well when you hear their life story. When you walk along, you always hear about what they’re doing or what’s happened to them. It’s very good both ways—walking and when you’re at the [hall] after you’re finished. It seems to have brought people closer together. (P4)

3.4.3. Sense of Belonging

I feel that the group is strong and we look forward to meeting up together, and I think that it has become caring and hopefully we can move on together by staying together. (P3)

You feel part of it and you want it to continue. I think that’s it. It’s a bit of loyalty to the group really. If we all said, ‘Oh, I can’t be arsed today’, it wouldn’t be a group, would it? (P6 and P7)

3.4.4. Acting on Empathy

There are some people with obvious problems and they’re getting through it their way, and that we do care about each other…. People don’t want to be a burden, but I think we can all realise that we’ve been through situations ourselves whereby we … [think] … ‘Hey, am I ever going to be able to do something like this again?’, and we can sympathise with people and help them through it. (P3)

For me, I’m just very happy if I see these different people enjoying themselves, getting on together, being sociable and being aware of each other and considerate to their needs without making a fuss. (P9)

4. Discussion

4.1. Mitigating Social Isolation

4.2. Social Elements of the Intervention

4.3. Mediating Social Experiences

4.4. Individual Social Wellbeing as an Outcome

4.5. Conceptual Model for Investigating the Effects of NBIs on Individual Social Wellbeing

4.6. Limitations of Research

4.7. Future Research

4.8. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Claire, R.; Gordon, M.; Kroon, M.; Reilly, C. The effects of social isolation on well-being and life satisfaction during pandemic. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, L. Loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 1161–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansford, J.E.; Sherman, A.M.; Antonucci, T.C. Satisfaction with Social Networks: An Examination of Socioemotional Selectivity Theory across Cohorts. Psychol. Aging 1998, 13, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivett, V.R.; Stevenson, M.L.; Zwane, C.H. Very-Old Rural Adults: Functional Status and Social Support. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2000, 19, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbakke, S.; Schwanen, T. Well-Being and Mobility: A Theoretical Framework and Literature Review Focusing on Older People. Mobilities 2014, 9, 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinney, J.E.L.; Scott, D.M.; Newbold, K.B. Transport Mobility Benefits and Quality of Life: A Time-Use Perspective of Elderly Canadians. Transp. Policy 2009, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, F.; Schwanen, T.I.M. ‘I Like to Go out to Be Energised by Different People’: An Exploratory Analysis of Mobility and Wellbeing in Later Life. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cattan, M.; White, M.; Bond, J.; Learmouth, A. Preventing Social Isolation and Loneliness among Older People: A Systematic Review of Health Promotion Interventions. Ageing Soc. 2005, 25, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Valtorta, N.; Hanratty, B. Loneliness, Isolation and the Health of Older Adults: Do We Need a New Research Agenda? J. R. Soc. Med. 2012, 105, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fakoya, O.A.; McCorry, N.K.; Donnelly, M. Loneliness and Social Isolation Interventions for Older Adults: A Scoping Review of Reviews. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steptoe, A.; Shankar, A.; Demakakos, P.; Wardle, J. Social Isolation, Loneliness, and All-Cause Mortality in Older Men and Women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kondo, M.; Jacoby, S.; South, E. Does Spending Time Outdoors Reduce Stress? A Review of Real-Time Stress Response to Outdoor Environments. Health Place 2018, 51, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Z.X.; Phua, A.; Chew, K.A.; Mohamed, J.S.; Perez, K.M.; Mangialasche, F.; Kivipelto, M.; Chen, C. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on lifestyle in a middle-aged and elderly population. Alzheimers Dement. 2021, 17 (Suppl. 10), 3057643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, J.; Everest, G.; Abbs, I. Will COVID-19 Be a Watershed Moment for Health Inequalities? The Health Foundation: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UK Government 2021. Social Distancing Review: Report. July 2021. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/999413/Social-Distancing-Review-Report.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Blundell, R.; Costa Dias, M.; Joye, R.; Xu, X. COVID-19 and Inequalities. Fisc. Stud. 2020, 41, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Robles, T.F.; Sbarra, D.A. Advancing Social Connection as a Public Health Priority in the United States. Am. Psychol. 2017, 72, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. A Connected Society: A Strategy for Tackling Loneliness–Laying the Foundations for Change. 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-connected-society-a-strategy-for-tackling-loneliness (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Department for Work & Pensions. 2010 to 2015 Government Policy: Older People. 2015. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/2010-to-2015-government-policy-older-people/2010-to-2015-government-policy-older-people (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- World Health Organization. Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/determinants-of-health (accessed on 29 May 2021).

- Cornwell, E.Y.; Waite, L.J. Social Disconnectedness, Perceived Isolation, and Health among Older Adults. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2009, 50, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dowds, G.; Currie, M.; Philip, L.; Masthoff, J. A Window to the Outside World. Digital Technology to Stimulate Imaginative Mobility for Housebound Older Adults in Rural Areas. In Geographies of Transport and Ageing; Curl, A., Musselwhite, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 101–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dickens, A.P.; Richards, S.H.; Greaves, C.J.; Campbell, J.L. Interventions Targeting Social Isolation in Older People: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn Jr, P.H.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L. Nature Contact and Human Health: A Research Agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marselle, M.R.; Hartig, T.; Cox, D.T.C.; de Bell, S.; Knapp, S.; Lindley, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Böhning-Gaese, K.; Braubach, M.; Cook, P.A.; et al. Pathways Linking Biodiversity to Human Health: A Conceptual Framework. Environ. Int. 2021, 150, 106420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. 2002. Available online: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/WHO_NMH_NPH_02.8.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- International Council on Active Ageing. Overview: The ICAA Model. Available online: https://www.icaa.cc/activeagingandwellness.htm (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Hunter, R.F.; Ball, K.; Sarmiento, O.L. Socially Awkward: How Can We Better Promote Walking as a Social Behaviour? Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 757–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, K.; Bauman, A.; Leslie, E.; Owen, N. Perceived Environmental Aesthetics and Convenience and Company Are Associated with Walking for Exercise among Australian Adults. Prev. Med. 2001, 33, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baert, V.; Gorus, E.; Mets, T.; Geerts, C.; Bautmans, I. Motivators and Barriers for Physical Activity in the Oldest Old: A Systematic Review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Hartig, T.; Staats, H. Psychological Benefits of Walking: Moderation by Company and Outdoor Environment. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2011, 3, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Andrews, M. When Walking in Nature Is Not Restorative—The Role of Prospect and Refuge. Health Place 2013, 20, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization Europe. Urban Green Spaces: A Brief for Ation. 2017. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/urban-health/publications/2017/urban-green-spaces-a-brief-for-action-2017 (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Shanahan, D.F.; Astell–Burt, T.; Barber, E.A.; Brymer, E.; Cox, D.T.C.; Dean, J.; Depledge, M.; Fuller, R.A.; Hartig, T.; Irvine, K.N.; et al. Nature–Based Interventions for Improving Health and Wellbeing: The Purpose, the People and the Outcomes. Sports 2019, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paths for All. What Is a Health Walk? Available online: https://www.pathsforall.org.uk/walking-for-health/health-walks/what-is-a-health-walk (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Marselle, M.R.; Irvine, K.N.; Warber, S.L. Examining Group Walks in Nature and Multiple Aspects of Well-Being: A Large-Scale Study. Ecopsychology 2014, 6, 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, K.N.; Marselle, M.R.; Melrose, A.; Warber, S.L. Group Outdoor Health Walks Using Activity Trackers: Measurement and Implementation Insight from a Mixed Methods Feasibility Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- South, J.; Giuntoli, G.; Kinsella, K.; Carless, D.; Long, J.; McKenna, J. Walking, Connecting and Befriending: A Qualitative Pilot Study of Participation in a Lay-Led Walking Group Intervention. J. Transp. Health 2017, 5, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensley, R.; Slade, A. Walking as a Meaningful Leisure Occupation: The Implications for Occupational Therapy. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 75, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, A.; Calderwood, C.; Hunter, G.; Murray, A. Physical Activity Investments That Work—Get Scotland Walking: A National Walking Strategy for Scotland. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gusi, N.; Reyes, M.C.; Gonzalez-Guerrero, J.L.; Herrera, E.; Garcia, J.M. Cost-Utility of a Walking Programme for Moderately Depressed, Obese, or Overweight Elderly Women in Primary Care: A Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelly, P.; Williamson, C.; Niven, A.G.; Hunter, R.; Mutrie, N.; Richards, J. Walking on Sunshine: Scoping Review of the Evidence for Walking and Mental Health. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Cauwenberg, J.; De Donder, L.; Clarys, P.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Buffel, T.; De Witte, N.; Dury, S.; Verté, D.; Deforche, B. Relationships between the Perceived Neighborhood Social Environment and Walking for Transportation among Older Adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 104, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAuley, E.; Blissmer, B.; Marquez, D.X.; Jerome, G.J.; Kramer, A.F.; Katula, J. Social Relations, Physical Activity, and Well-Being in Older Adults. Prev. Med. 2000, 31, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, Y.; Ura, C.; Yamaguchi, T.; Murai, T.; Isahai, M.; Kaiho, A.; Yamagami, T.; Tanaka, S.; Miyamae, F.; Sugiyama, M.; et al. Effects of Intervention Using a Community-Based Walking Program for Prevention of Mental Decline: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutrie, N.; Doolin, O.; Fitzsimons, C.F.; Grant, P.M.; Granat, M.; Grealy, M.; Macdonald, H.; MacMillan, F.; McConnachie, A.; Rowe, D.A.; et al. Increasing Older Adults’ Walking through Primary Care: Results of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Fam. Pract. 2012, 29, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watson, N.; Milat, A.J.; Thomas, M.; Currie, J. The Feasibility and Effectiveness of Pram Walking Groups for Postpartum Women in Western Sydney. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2005, 16, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, K.; Edwards, H. The Effects of Exercise and Social Support on Mothers Reporting Depressive Symptoms: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2003, 12, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armstrong, K.; Edwards, H. The Effectiveness of a Pram-Walking Exercise Programme in Reducing Depressive Symptomatology for Postnatal Women. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2004, 10, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hawkins, J.L.; Thirlaway, K.J.; Backx, K.; Clayton, D.A. Allotment Gardening and Other Leisure Activities for Stress Reduction and Healthy Aging. HortTechnology 2011, 21, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dawson, J.; Boller, I.; Foster, C.; Hillsdon, M. Evaluation of Changes to Physical Activity Amongst People Who Attend the Walking the Way to Health Initiative (WHI); The Countryside Agency: London, UK, 2006.

- Pollard, T.M.; Guell, C.; Morris, S. Communal Therapeutic Mobility in Group Walking: A Meta-Ethnography. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 262, 113241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villalba van Dijk, L.; Cacace, M.; Nolte, E.; Sach, T.; Fordham, F.; Suhrcke, M. Costing the Walking for Health Programme; Natural England Commissioned Reports, No. 099 (NECR); Her Majesty’s Stationary Office: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Warber, S.L.; DeHudy, A.A.; Bialko, M.F.; Marselle, M.R.; Irvine, K.N. Addressing “Nature-Deficit Disorder”: A Mixed Methods Pilot Study of Young Adults Attending a Wilderness Camp. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, 651827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McNeill, L.H.; Kreuter, M.W.; Subramanian, S.V. Social Environment and Physical Activity: A Review of Concepts and Evidence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, L.; Kremers, S.; Walsh, A.; Brug, H. How Is Your Walking Group Running? Health Educ. 2006, 106, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Bezner, J.; Steinhardt, M. The Conceptualization and Measurement of Perceived Wellness: Integrating Balance across and within Dimensions. Am. J. Health Promot. 1997, 11, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Tsai, J.; Kao, S. Public Health, Social Determinants of Health, and Public Policy. J. Med. Sci. 2009, 29, 043–059. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, G.L. The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Mühlan, H.; Power, M. The Eurohis-Qol 8-Item Index: Psychometric Results of a Cross-Cultural Field Study. Eur. J. Public Health 2005, 16, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerndahl, D.; Oyiriaru, D. Assessing the Biopsychosociospiritual Model in Primary Care: Development of the Biopsychosociospiritual Inventory (Biopssi). Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2007, 37, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S. Social Relationships and Health. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, H.; Arber, S.; Fee, L.; Ginn, J. The Influence of Social Support and Social Capital on Health: A Review and Analysis of British Data; Health Education Authority: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, 1st ed.; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano, R.M. Toward a Neighborhood Resource-Based Theory of Social Capital for Health: Can Bourdieu and Sociology Help? Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, H.; Rickwood, D. Measuring Social Capital at the Individual Level: Personal Social Capital, Values and Psychological Distress. J. Public Ment. Health 2000, 2, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, R.; Kearns, A. Social Cohesion, Social Capital and the Neighbourhood. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2125–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carron, A.V.; Widmeyer, W.N.; Brawley, L.R. Group Cohesion and Individual Adherence to Physical Activity. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1988, 10, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Definition of Health. Available online: http://www.who.int/suggestions/faq/en/ (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Irvine, K.N.; Warber, S.L.; Devine-Wright, P.; Gaston, K.J. Understanding Urban Green Space as a Health Resource: A Qualitative Comparison of Visit Motivation and Derived Effects among Park Users in Sheffield, UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fava, G.A.; Sonino, N. The Biopsychosocial Model Thirty Years Later. Psychother. Psychosom. 2008, 77, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, D.D.; Chappel, J.N. Spirituality and Medical Practice. J. Fam. Pract. 1992, 35, 201, 205–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bann, C.M.; Kobau, R.; Lewis, M.A.; Zack, M.M.; Luncheon, C.; Thompson, W.W. Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Public Health Surveillance Well-Being Scale. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 1031–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M.; Waterman, M.B. Dimensions of Well-Being and Mental Health in Adulthood. In Well-Being: Positive Development across the Life Course; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 477–497. [Google Scholar]

- Lui, P.P.; Fernando, G.A. Development and Initial Validation of a Multidimensional Scale Assessing Subjective Well-Being: The Well-Being Scale (Webs). Psychol. Rep. 2018, 121, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Linton, M.-J.; Dieppe, P.; Medina-Lara, A. Review of 99 Self-Report Measures for Assessing Well-Being in Adults: Exploring Dimensions of Well-Being and Developments over Time. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supranowicz, P.; Paź, M. Holistic Measurement of Well-Being: Psychometric Properties of the Physical, Mental and Social Well-Being Scale (Pmsw-21) for Adults. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2014, 65, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paradies, Y.; Stevens, M. Conceptual Diagrams in Public Health Research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: The New Medical Research Council Guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hyett, N.; Kenny, A.; Dickson-Swift, V. Methodology or method? A critical review of qualitative case study reports. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 23606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, C.; Waters, D.L.; Buttery, Y.; van Heezik, Y. The Impacts of Ageing on Connection to Nature: The Varied Responses of Older Adults. Health Place 2019, 56, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdridge, D. Phenomenology and critical social psychology: Directions and debates in theory and research. Soc. Person Psychol. 2008, 2, 1126–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, A.J.; Durepos, G.; Wiebe, E. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (Vols. 1-0); SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolley, E.E.; Ulin, P.R.; Mack, N.; Robinson, E.T.; Succop, S.M. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016; 480p. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruce, S.; Yearley, S. The Sage Dictionary of Sociology; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, S.; Guell, C.; Pollard, T.M. Group Walking as a “Lifeline”: Understanding the Place of Outdoor Walking Groups in Women’s Lives. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 238, 112489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, B.P.; Dodd-Reynolds, C.J.; Oliver, E.J. Inequities and Inequalities in Outdoor Walking Groups: A Scoping Review. Public Health Rev. 2020, 41, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurawik, M.A. Socio-Environmental Influences on Nordic Walking Participation and Their Implications for Well-Being. J. Outdoor Recreat. 2020, 29, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiber, D.A. Toward an applied social psychology of leisure. J. Leis. Res. 2020, 51, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, B.T.; Schulz, A.J.; Mentz, G.; Israel, B.A.; Sand, S.L.; Reyes, A.G.; Hoston, B.; Richardson, D.; Gamboa, C.; Rowe, Z.; et al. Leader behaviors, group cohesion and participation in a walking group program. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coley, R.L.; Sullivan, W.C.; Kuo, F.E. Where Does Community Grow?: The Social Context Created by Nature in Urban Public Housing. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 468–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C.; Coley, R.L.; Brunson, L. Fertile Ground for Community: Inner-City Neighborhood Common Spaces. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1998, 26, 823–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavell, M.A.; Leiferman, J.A.; Gascon, M.; Braddick, F.; Gonzalez, J.C.; Litt, J.S. Nature-Based Social Prescribing in Urban Settings to Improve Social Connectedness and Mental Well-Being: A Review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2019, 6, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddon, L. Therapeutic or Detrimental Mobilities? Walking Groups for Older Adults. Health Place 2020, 63, 102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, V.; More, K.R. Developing Scotland’s first Green Health Prescription Pathway: A one-stop shop for nature-based intervention referrals. Front. Psychol. 2022, 33, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickerdike, L.; Booth, A.; Wilson, P.M.; Farley, K.; Wright, K. Social prescribing: Less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, H.J.; Camic, P.M.; Lockyer, B.; Thomson, L.J. Non-clinical community interventions: A systematised review of social prescribing schemes. Arts Health 2018, 10, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Themes/Sub-Themes | Description |

|---|---|

| Theme 1. Programmatic Elements Fostering Engagement | The programme provides the opportunity to be part of a group and a structure that attends to the needs of inexperienced or physically challenged individuals. |

| Theme 2. Spontaneous Mixing and Mingling | Being part of the group walk fosters casual interpersonal interactions through spontaneous mixing during and after the walk. |

| Theme 3. Evolving Social Experiences | The spontaneous socialising provides for largely positive social experiences illustrated in four sub-themes. |

| Counteracting Loneliness | The group walks help combat loneliness and social isolation. |

| Anticipating Regular Contact | The group walks provide an opportunity for regular contact with other people, breaking up routine, and something to look forward to carrying out. |

| Supportive Socialising | The group process itself (i.e., the chatting and the camaraderie) helps people join and complete walks they would not have attempted on their own. |

| Emerging Group Cohesion | Unity and group cohesion emerge in the context of making decisions about the walking. |

| Theme 4. Achieving Individual Social Wellbeing | Participants demonstrated increased individual social wellbeing illustrated in four sub-themes. |

| Expanding Social Networks | Participants had a sense of expanding social networks and learning about people in relation to the places around them. |

| Making Meaningful Relationships | Walkers furthered their ability to make and maintain meaningful relationships and develop friendships. |

| Sense of Belonging | The sense of belonging to the walking group, including responsibility and loyalty, developed over time. |

| Acting on Empathy | Being part of the walking group fostered a sense of respect and empathy for others’ physical abilities, needs, and individual differences. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Irvine, K.N.; Fisher, D.; Marselle, M.R.; Currie, M.; Colley, K.; Warber, S.L. Social Isolation in Older Adults: A Qualitative Study on the Social Dimensions of Group Outdoor Health Walks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095353

Irvine KN, Fisher D, Marselle MR, Currie M, Colley K, Warber SL. Social Isolation in Older Adults: A Qualitative Study on the Social Dimensions of Group Outdoor Health Walks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(9):5353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095353

Chicago/Turabian StyleIrvine, Katherine N., Daniel Fisher, Melissa R. Marselle, Margaret Currie, Kathryn Colley, and Sara L. Warber. 2022. "Social Isolation in Older Adults: A Qualitative Study on the Social Dimensions of Group Outdoor Health Walks" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 9: 5353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095353

APA StyleIrvine, K. N., Fisher, D., Marselle, M. R., Currie, M., Colley, K., & Warber, S. L. (2022). Social Isolation in Older Adults: A Qualitative Study on the Social Dimensions of Group Outdoor Health Walks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5353. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095353