Mechanism of Generation of Therapy Related Leukemia in Response to Anti-Topoisomerase II Agents

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| TOP2 poison * associated(* such as etoposide, teniposide mitroxantrone, epirubicin) | Alkylating agent $ associated($ such as cyclophosphamide, melphalan, chlorambucil, and nitrosoureas) | |

|---|---|---|

| Latency period | Short, <2 years | 2–8 years |

| Chromosome abnormalities | Recurrent translocations especially involving MLL at 11q23 and t(15;17)(PML-RARA), t(8,21)(AML-ETO) | Deletions involving Chr 5 and 7 |

| Complex Karyotype | Rare | Frequent |

| Preceded by myelodisplastic syndrome | Rare | Frequent |

| Age association | Younger | Older |

2. TOP2 and TOP2 Poisons

| Chemical class | Examples |

|---|---|

| Epipodophyllotoxins | Etoposide, Teniposode |

| Anthracylines | Doxorubicin, Epirubicin, Daunorubicin, Idarubicin, Aclarubicin |

| Anthacenedione | Mitoxantrone |

| Acridines | m-AMSA (amsacrine), m-AMCA, AMCA, DACA |

| Quinalones | Voreloxin |

| Benzo[c]phenanthridine alkaloid | NK314 |

3. TOP2 Poisons and Chromosome Translocations

4. Conclusions and Possible Approaches to Reducing T-AML Associated Chromosome Translocations

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Mauritzson, N.; Albin, M.; Rylander, L.; Billstrom, R.; Ahlgren, T.; Mikoczy, Z.; Bjork, J.; Stromberg, U.; Nilsson, P.G.; Mitelman, F.; Hagmar, L.; Johansson, B. Pooled analysis of clinical and cytogenetic features in treatment-related and de novo adult acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes based on a consecutive series of 761 patients analyzed 1976–1993 and on 5,098 unselected cases reported in the literature 1974–2001. Leukemia 2002, 16, 2366–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, W.; Haferlach, T.; Schnittger, S.; Hiddemann, W.; Schoch, C. Prognosis in therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia and impact of karyotype. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 2510–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijiya, N.; Hudson, M.M.; Lensing, S.; Zacher, M.; Onciu, M.; Behm, F.G.; Razzouk, B.I.; Ribeiro, R.C.; Rubnitz, J.E.; Sandlund, J.T.; Rivera, G.K.; Evans, W.E.; Relling, M.V.; Pui, C.H. Cumulative incidence of secondary neoplasms as a first event after childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA 2007, 297, 1207–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Praga, C.; Bergh, J.; Bliss, J.; Bonneterre, J.; Cesana, B.; Coombes, R.C.; Fargeot, P.; Folin, A.; Fumoleau, P.; Giuliani, R.; Kerbrat, P.; Hery, M.; Nilsson, J.; Onida, F.; Piccart, M.; Shepherd, L.; Therasse, P.; Wils, J.; Rogers, D. Risk of acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome in trials of adjuvant epirubicin for early breast cancer: Correlation with doses of epirubicin and cyclophosphamide. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 4179–4191. [Google Scholar]

- Le Deley, M.C.; Suzan, F.; Cutuli, B.; Delaloge, S.; Shamsaldin, A.; Linassier, C.; Clisant, S.; de Vathaire, F.; Fenaux, P.; Hill, C. Anthracyclines, mitoxantrone, radiotherapy, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: Risk factors for leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome after breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 292–300. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, G.; Fianchi, L.; Pagano, L.; Voso, M.T. Incidence and susceptibility to therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 184, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J.D.; Olney, H.J. International workshop on the relationship of prior therapy to balanced chromosome aberrations in therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes and acute leukemia: Overview report. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2002, 33, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschalek, R. Mechanisms of leukemogenesis by MLL fusion proteins. Br. J. Haematol. 2011, 152, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Kowarz, E.; Hofmann, J.; Renneville, A.; Zuna, J.; Trka, J.; Ben Abdelali, R.; Macintyre, E.; De Braekeleer, E.; De Braekeleer, M.; Delabesse, E.; de Oliveira, M.P.; Cave, H.; Clappier, E.; van Dongen, J.J.; Balgobind, B.V.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; Beverloo, H.B.; Panzer-Grumayer, R.; Teigler-Schlegel, A.; Harbott, J.; Kjeldsen, E.; Schnittger, S.; Koehl, U.; Gruhn, B.; Heidenreich, O.; Chan, L.C.; Yip, S.F.; Krzywinski, M.; Eckert, C.; Moricke, A.; Schrappe, M.; Alonso, C.N.; Schafer, B.W.; Krauter, J.; Lee, D.A.; Zur Stadt, U.; Te Kronnie, G.; Sutton, R.; Izraeli, S.; Trakhtenbrot, L.; Lo Nigro, L.; Tsaur, G.; Fechina, L.; Szczepanski, T.; Strehl, S.; Ilencikova, D.; Molkentin, M.; Burmeister, T.; Dingermann, T.; Klingebiel, T.; Marschalek, R. New insights to the MLL recombinome of acute leukemias. Leukemia 2009, 23, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar]

- Super, H.J.; McCabe, N.R.; Thirman, M.J.; Larson, R.A.; Le Beau, M.M.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, J.; Philip, P.; Diaz, M.O.; Rowley, J.D. Rearrangements of the MLL gene in therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia in patients previously treated with agents targeting DNA-topoisomerase II. Blood 1993, 82, 3705–3711. [Google Scholar]

- Krivtsov, A.V.; Twomey, D.; Feng, Z.; Stubbs, M.C.; Wang, Y.; Faber, J.; Levine, J.E.; Wang, J.; Hahn, W.C.; Gilliland, D.G.; Golub, T.R.; Armstrong, S.A. Transformation from committed progenitor to leukaemia stem cell initiated by MLL-AF9. Nature 2006, 442, 818–822. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, S.K.; Ottone, T.; Schlenk, R.F.; Xiao, Y.; Wiemels, J.L.; Mitra, M.E.; Bernasconi, P.; Di Raimondo, F.; Stanghellini, M.T.; Marco, P.; Mays, A.N.; Dohner, H.; Sanz, M.A.; Amadori, S.; Grimwade, D.; Lo-Coco, F. Analysis of t(15;17) chromosomal breakpoint sequences in therapy-related versus de novo acute promyelocytic leukemia: Association of DNA breaks with specific DNA motifs at PML and RARA loci. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2010, 49, 726–732. [Google Scholar]

- Ottone, T.; Hasan, S.K.; Montefusco, E.; Curzi, P.; Mays, A.N.; Chessa, L.; Ferrari, A.; Conte, E.; Noguera, N.I.; Lavorgna, S.; Ammatuna, E.; Divona, M.; Bovetti, K.; Amadori, S.; Grimwade, D.; Lo-Coco, F. Identification of a potential “hotspot” DNA region in the RUNX1 gene targeted by mitoxantrone in therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia with t(16;21) translocation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2009, 48, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, A.N.; Osheroff, N.; Xiao, Y.; Wiemels, J.L.; Felix, C.A.; Byl, J.A.; Saravanamuttu, K.; Peniket, A.; Corser, R.; Chang, C.; Hoyle, C.; Parker, A.N.; Hasan, S.K.; Lo-Coco, F.; Solomon, E.; Grimwade, D. Evidence for direct involvement of epirubicin in the formation of chromosomal translocations in t(15;17) therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 2009, 15, 326–330. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, S.K.; Mays, A.N.; Ottone, T.; Ledda, A.; La Nasa, G.; Cattaneo, C.; Borlenghi, E.; Melillo, L.; Montefusco, E.; Cervera, J.; Stephen, C.; Satchi, G.; Lennard, A.; Libura, M.; Byl, J.A.; Osheroff, N.; Amadori, S.; Felix, C.A.; Voso, M.T.; Sperr, W.R.; Esteve, J.; Sanz, M.A.; Grimwade, D.; Lo-Coco, F. Molecular analysis of t(15;17) genomic breakpoints in secondary acute promyelocytic leukemia arising after treatment of multiple sclerosis. Blood 2008, 112, 3383–3390. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry, A.R.; Felix, C.A.; Whitmarsh, R.J.; Mason, A.; Reiter, A.; Cassinat, B.; Parry, A.; Walz, C.; Wiemels, J.L.; Segal, M.R.; Ades, L.; Blair, I.A.; Osheroff, N.; Peniket, A.J.; Lafage-Pochitaloff, M.; Cross, N.C.; Chomienne, C.; Solomon, E.; Fenaux, P.; Grimwade, D. DNA topoisomerase II in therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Voltz, R.; Starck, M.; Zingler, V.; Strupp, M.; Kolb, H.J. Mitoxantrone therapy in multiple sclerosis and acute leukaemia: a case report out of 644 treated patients. Mult. Scler. 2004, 10, 472–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelmes, H.U.; Grue, P.; Feineis, S.; Straub, T.; Boege, F. Active DNA topoisomerase IIa is a component of the salt-stable centrosome core. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 38823–38830. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, S.M.; Tretter, E.M.; Schmidt, B.H.; Berger, J.M. All tangled up: How cells direct, manage and exploit topoisomerase function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvier, O.; Hirano, T. A role of topoisomerase II in linking DNA replication to chromosome condensation. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 160, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, N.; Parvin, J.D. DNA topoisomerase IIa is required for RNA polymerase II transcription on chromatin templates. Nature 2001, 413, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wold, M.S.; Li, J.J.; Kelly, T.J.; Liu, L.F. Roles of DNA topoisomerases in simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 950–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padget, K.; Pearson, A.D.; Austin, C.A. Quantitation of DNA topoisomerase IIa and b in human leukaemia cells by immunoblotting. Leukemia 2000, 14, 1997–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosperi, E.; Negri, C.; Marchese, G.; Ricotti, G.C. Expression of the 170-kDa and 180-kDa isoforms of DNA topoisomerase II in resting and proliferating human lymphocytes. Cell Prolif. 1994, 27, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onda, T.; Toyoda, E.; Miyazaki, O.; Seno, C.; Kagaya, S.; Okamoto, K.; Nishikawa, K. NK314, a novel topoisomerase II inhibitor, induces rapid DNA double-strand breaks and exhibits superior antitumor effects against tumors resistant to other topoisomerase II inhibitors. Cancer Lett. 2008, 259, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, E.; Kagaya, S.; Cowell, I.G.; Kurosawa, A.; Kamoshita, K.; Nishikawa, K.; Iiizumi, S.; Koyama, H.; Austin, C.A.; Adachi, N. NK314, a topoisomerase II inhibitor that specifically targets the alpha isoform. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 23711–23720. [Google Scholar]

- Hisatomi, T.; Sueoka-Aragane, N.; Sato, A.; Tomimasu, R.; Ide, M.; Kurimasa, A.; Okamoto, K.; Kimura, S.; Sueoka, E. NK314 potentiates anti-tumor activity with adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma cellsby inhibition of dual targets on topoisomerase IIα and DNA-dependent protein kinase. Blood 2011, 117, 3575–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawtin, R.E.; Stockett, D.E.; Byl, J.A.W.; McDowell, R.S.; Tan, N.; Arkin, M.R.; Conroy, A.; Yang, W.; Osheroff, N.; Fox, J.A. Voreloxin is an anticancer quinolone derivative that intercalates DNA and poisons topoisomerase II. PLoS ONE 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, C.A.; Patel, S.; Ono, K.; Nakane, H.; Fisher, L.M. Site-specific DNA cleavage by mammalian DNA topoisomerase II induced by novel flavone and catechin derivatives. Biochem. J. 1992, 282, 883–889. [Google Scholar]

- Azarova, A.M.; Lin, R.-K.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Liu, L.F.; Lin, C.-P.; Lyu, Y.L. Genistein induces topoisomerase IIb- and proteasome-mediated DNA sequence rearrangements: Implications in infant leukemia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 399, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Lazaro, M.; Calderon-Montano, J.M.; Burgos-Moron, E.; Austin, C.A. Green tea constituents (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) and gallic acid induce topoisomerase I- and topoisomerase II-DNA complexes in cells mediated by pyrogallol-induced hydrogen peroxide. Mutagenesis 2011, 26, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Lazaro, M.; Willmore, E.; Austin, C.A. Cells lacking DNA topoisomerase IIb are resistant to genistein. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Lazaro, M.; Willmore, E.; Austin, C.A. The dietary flavonoids myricetin and fisetin act as dual inhibitors of DNA topoisomerases I and II in cells. Mutat. Res. 2010, 696, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Habermeyer, M.; Fritz, J.; Barthelmes, H.U.; Christensen, M.O.; Larsen, M.K.; Boege, F.; Marko, D. Anthocyanidins modulate the activity of human DNA topoisomerases I and II and affect cellular DNA integrity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005, 18, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A. Dietary flavonoids and the MLL gene: A pathway to infant leukemia? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 4411–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani, S.; Janssen, J.; Maas, L.M.; Godschalk, R.W.L.; Nijhuis, J.G.; van Schooten, F.J. Dietary flavonoids induce MLL translocations in primary human CD34+ cells. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 1703–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, S.M.; Phillips, D.R.; Crothers, D.M. Characterization of covalent Adriamycin-DNA adducts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 11561–11565. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, L.P.; Rephaeli, A.; Nudelman, A.; Phillips, D.R.; Cutts, S.M. Doxorubicin-DNA adducts induce a non-topoisomerase II-mediated form of cell death. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 4863–4871. [Google Scholar]

- Bilardi, R.A.; Kimura, K.I.; Phillips, D.R.; Cutts, S.M. Processing of anthracycline-DNA adducts via DNA replication and interstrand crosslink repair pathways. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 83, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.S.; Cutts, S.M.; Cullinane, C.; Phillips, D.R. Formaldehyde activation of mitoxantrone yields CpG and CpA specific DNA adducts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.S.; Buley, T.; Evison, B.J.; Cutts, S.M.; Neumann, G.M.; Iskander, M.N.; Phillips, D.R. A molecular understanding of mitoxantrone-DNA adduct formation: Effect of cytosine methylation and flanking sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 18814–18823. [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz, D. A critical evaluation of the mechanisms of action proposed for the antitumor effects of the anthracycline antibiotics adriamycin and daunorubicin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 57, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broeker, P.L.; Super, H.G.; Thirman, M.J.; Pomykala, H.; Yonebayashi, Y.; Tanabe, S.; Zeleznik-Le, N.; Rowley, J.D. Distribution of 11q23 breakpoints within the MLL breakpoint cluster region in de novo acute leukemia and in treatment-related acute myeloid leukemia: Correlation with scaffold attachment regions and topoisomerase II consensus binding sites. Blood 1996, 87, 1912–1922. [Google Scholar]

- Cimino, G.; Rapanotti, M.C.; Biondi, A.; Elia, L.; Lo Coco, F.; Price, C.; Rossi, V.; Rivolta, A.; Canaani, E.; Croce, C.M.; Mandelli, F.; Greaves, M. Infant acute leukemias show the same biased distribution of ALL1 gene breaks as topoisomerase II related secondary acute leukemias. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 2879–2883. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel, M.; Gillert, E.; Angermuller, S.; Hensel, J.P.; Heidel, F.; Lode, M.; Leis, T.; Biondi, A.; Haas, O.A.; Strehl, S.; Panzer-Grumayer, E.R.; Griesinger, F.; Beck, J.D.; Greil, J.; Fey, G.H.; Uckun, F.M.; Marschalek, R. Biased distribution of chromosomal breakpoints involving the MLL gene in infants versus children and adults with t(4;11) ALL. Oncogene 2001, 20, 2900–2907. [Google Scholar]

- De Braekeleer, M.; Morel, F.; Le Bris, M.J.; Herry, A.; Douet-Guilbert, N. The MLL gene and translocations involving chromosomal band 11q23 in acute leukemia. Anticancer Res. 2005, 25, 1931–1944. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, F.E.; Patheal, S.L.; Biondi, A.; Brandalise, S.; Cabrera, M.E.; Chan, L.C.; Chen, Z.; Cimino, G.; Cordoba, J.C.; Gu, L.J.; Hussein, H.; Ishii, E.; Kamel, A.M.; Labra, S.; Magalhaes, I.Q.; Mizutani, S.; Petridou, E.; de Oliveira, M.P.; Yuen, P.; Wiemels, J.L.; Greaves, M.F. Transplacental chemical exposure and risk of infant leukemia with MLL gene fusion. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 2542–2546. [Google Scholar]

- Strissel, P.L.; Strick, R.; Tomek, R.J.; Roe, B.A.; Rowley, J.D.; Zeleznik-Le, N.J. DNA structural properties of AF9 are similar to MLL and could act as recombination hot spots resulting in MLL/AF9 translocations and leukemogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 9, 1671–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strissel, P.L.; Strick, R.; Rowley, J.D.; Zeleznik-Le, N.J. An in vivo topoisomerase II cleavage site and a DNase I hypersensitive site colocalize near exon 9 in the MLL breakpoint cluster region. Blood 1998, 92, 3793–3803. [Google Scholar]

- Scharf, S.; Zech, J.; Bursen, A.; Schraets, D.; Oliver, P.L.; Kliem, S.; Pfitzner, E.; Gillert, E.; Dingermann, T.; Marschalek, R. Transcription linked to recombination: A gene-internal promoter coincides with the recombination hot spot II of the human MLL gene. Oncogene 2006, 26, 1361–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, T.; Metzler, M.; Reinhardt, D.; Viehmann, S.; Borkhardt, A.; Reichel, M.; Stanulla, M.; Schrappe, M.; Creutzig, U.; Ritter, J.; Leis, T.; Jacobs, U.; Harbott, J.; Beck, J.D.; Rascher, W.; Repp, R. Analysis of t(9;11) chromosomal breakpoint sequences in childhood acute leukemia: Almost identical MLL breakpoints in therapy-related AML after treatment without etoposides. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2003, 36, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffini, L.J.; Slater, D.J.; Rappaport, E.F.; Lo Nigro, L.; Cheung, N.K.; Biegel, J.A.; Nowell, P.C.; Lange, B.J.; Felix, C.A. Panhandle and reverse-panhandle PCR enable cloning of der(11) and der(other) genomic breakpoint junctions of MLL translocations and identify complex translocation of MLL, AF-4, and CDK6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 4568–4573. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh, R.J.; Saginario, C.; Zhuo, Y.; Hilgenfeld, E.; Rappaport, E.F.; Megonigal, M.D.; Carroll, M.; Liu, M.; Osheroff, N.; Cheung, N.K.; Slater, D.J.; Ried, T.; Knutsen, T.; Blair, I.A.; Felix, C.A. Reciprocal DNA topoisomerase II cleavage events at 5'-TATTA-3' sequences in MLL and AF-9 create homologous single-stranded overhangs that anneal to form der(11) and der(9) genomic breakpoint junctions in treatment-related AML without further processing. Oncogene 2003, 22, 8448–8459. [Google Scholar]

- Strick, R.; Zhang, Y.; Emmanuel, N.; Strissel, P.L. Common chromatin structures at breakpoint cluster regions may lead to chromosomal translocations found in chronic and acute leukemias. Hum. Genet. 2006, 119, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Strissel, P.; Strick, R.; Chen, J.; Nucifora, G.; Le Beau, M.M.; Larson, R.A.; Rowley, J.D. Genomic DNA breakpoints in AML1/RUNX1 and ETO cluster with topoisomerase II DNA cleavage and DNase I hypersensitive sites in t(8;21) leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 3070–3075. [Google Scholar]

- Dreszer, T.R.; Karolchik, D.; Zweig, A.S.; Hinrichs, A.S.; Raney, B.J.; Kuhn, R.M.; Meyer, L.R.; Wong, M.; Sloan, C.A.; Rosenbloom, K.R.; Roe, G.; Rhead, B.; Pohl, A.; Malladi, V.S.; Li, C.H.; Learned, K.; Kirkup, V.; Hsu, F.; Harte, R.A.; Guruvadoo, L.; Goldman, M.; Giardine, B.M.; Fujita, P.A.; Diekhans, M.; Cline, M.S.; Clawson, H.; Barber, G.P.; Haussler, D.; James Kent, W. The UCSC Genome Browser database: Extensions and updates 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D918–D923. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom, K.R.; Dreszer, T.R.; Long, J.C.; Malladi, V.S.; Sloan, C.A.; Raney, B.J.; Cline, M.S.; Karolchik, D.; Barber, G.P.; Clawson, H.; Diekhans, M.; Fujita, P.A.; Goldman, M.; Gravell, R.C.; Harte, R.A.; Hinrichs, A.S.; Kirkup, V.M.; Kuhn, R.M.; Learned, K.; Maddren, M.; Meyer, L.R.; Pohl, A.; Rhead, B.; Wong, M.C.; Zweig, A.S.; Haussler, D.; Kent, W.J. ENCODE whole-genome data in the UCSC Genome Browser: Update 2012. Nucl. Acids Res. 2012, 40, D912–D917. [Google Scholar]

- Celniker, S.E.; Dillon, L.A.; Gerstein, M.B.; Gunsalus, K.C.; Henikoff, S.; Karpen, G.H.; Kellis, M.; Lai, E.C.; Lieb, J.D.; MacAlpine, D.M.; Micklem, G.; Piano, F.; Snyder, M.; Stein, L.; White, K.P.; Waterston, R.H. Unlocking the secrets of the genome. Nature 2009, 459, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Ju, B.G.; Lunyak, V.V.; Perissi, V.; Garcia-Bassets, I.; Rose, D.W.; Glass, C.K.; Rosenfeld, M.G. A topoisomerase IIb-mediated dsDNA break required for regulated transcription. Science 2006, 312, 1798–1802. [Google Scholar]

- Perillo, B.; Ombra, M.N.; Bertoni, A.; Cuozzo, C.; Sacchetti, S.; Sasso, A.; Chiariotti, L.; Malorni, A.; Abbondanza, C.; Avvedimento, E.V. DNA oxidation as triggered by H3K9me2 demethylation drives estrogen-induced gene expression. Science 2008, 319, 202–206. [Google Scholar]

- Haffner, M.C.; Aryee, M.J.; Toubaji, A.; Esopi, D.M.; Albadine, R.; Gurel, B.; Isaacs, W.B.; Bova, G.S.; Liu, W.; Xu, J.; Meeker, A.K.; Netto, G.; De Marzo, A.M.; Nelson, W.G.; Yegnasubramanian, S. Androgen-induced TOP2B-mediated double-strand breaks and prostate cancer gene rearrangements. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, S.; Wang, H.; Hanna, N.; Miller, W.H., Jr. Topoisomerase IIb negatively modulates retinoic acid receptora function: A novel mechanism of retinoic acid resistance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 2066–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.E.; Berney, J.J.; North, P.S.; Khan, Z.; Wilson, E.L.; Jacobs, P.; Ali, M. Evidence for the involvement of DNA topoisomerase II in neutrophil-granulocyte differentiation. Leukemia 1987, 1, 653–659. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Desai, S.D.; Ting, C.-Y.; Hwang, J.; Liu, L.F. 26 S proteasome-mediated degradation of topoisomerase ii cleavable complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 40652–40658. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.F.; Wang, J.C. Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 7024–7027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

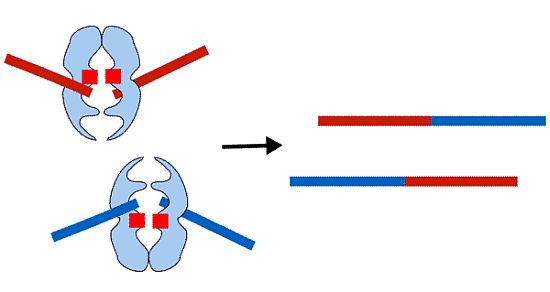

- Cowell, I.G.; Sondka, Z.; Smith, K.; Lee, K.C.; Manville, C.; Sidorczuk-Lesthuruge, M.; Rance, H.A.; Padget, K.; Jackson, G.H.; Adachi, N.; Austin, C.A. A model for MLL translocations in therapy-related leukemia involving topoisomerase IIβ mediated DNA strand breaks and gene proximity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaburn, K.J.; Misteli, T.; Soutoglou, E. Spatial genome organization in the formation of chromosomal translocations. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2007, 17, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.R.; Pombo, A. Intermingling of chromosome territories in interphase suggests role in translocations and transcription-dependent associations. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P.R. A model for all genomes: The role of transcription factories. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 395, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faro-Trindade, I.; Cook, P.R. Transcription factories: Structures conserved during differentiation and evolution. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006, 34, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, C.S.; Chakalova, L.; Brown, K.E.; Carter, D.; Horton, A.; Debrand, E.; Goyenechea, B.; Mitchell, J.A.; Lopes, S.; Reik, W.; Fraser, P. Active genes dynamically colocalize to shared sites of ongoing transcription. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfelder, S.; Sexton, T.; Chakalova, L.; Cope, N.F.; Horton, A.; Andrews, S.; Kurukuti, S.; Mitchell, J.A.; Umlauf, D.; Dimitrova, D.S.; Eskiw, C.H.; Luo, Y.; Wei, C.-L.; Ruan, Y.; Bieker, J.J.; Fraser, P. Preferential associations between co-regulated genes reveal a transcriptional interactome in erythroid cells. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, C.S.; Chakalova, L.; Mitchell, J.A.; Horton, A.; Wood, A.L.; Bolland, D.J.; Corcoran, A.E.; Fraser, P. Myc dynamically and preferentially relocates to a transcription factory occupied by Igh. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirault, M.E.; Boucher, P.; Tremblay, A. Nucleotide-resolution mapping of topoisomerase-mediated and apoptotic DNA strand scissions at or near an MLL translocation hotspot. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 79, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, C.J.; Villalobos, M.J.; Diaz, M.O.; Vaughan, A.T. Apoptotic triggers initiate translocations within the MLL gene involving the nonhomologous end joining repair system. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4550–4555. [Google Scholar]

- Stanulla, M.; Wang, J.; Chervinsky, D.S.; Thandla, S.; Aplan, P.D. DNA cleavage within the MLL breakpoint cluster region is a specific event which occurs as part of higher-order chromatin fragmentation during the initial stages of apoptosis. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997, 17, 4070–4079. [Google Scholar]

- Capranico, G.; Binaschi, M. DNA sequence selectivity of topoisomerases and topoisomerase poisons. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1400, 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lovett, B.D.; Lo Nigro, L.; Rappaport, E.F.; Blair, I.A.; Osheroff, N.; Zheng, N.; Megonigal, M.D.; Williams, W.R.; Nowell, P.C.; Felix, C.A. Near-precise interchromosomal recombination and functional DNA topoisomerase II cleavage sites at MLL and AF-4 genomic breakpoints in treatment-related acute lymphoblastic leukemia with t(4;11) translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 9802–9807. [Google Scholar]

- Azarova, A.M.; Lyu, Y.L.; Lin, C.P.; Tsai, Y.C.; Lau, J.Y.; Wang, J.C.; Liu, L.F. Roles of DNA topoisomerase II isozymes in chemotherapy and secondary malignancies. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA 2007, 104, 11014–11019. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Huang, K.-C.; Yamasaki, E.F.; Chan, K.K.; Chohan, L.; Snapka, R.M. XK469, a selective topoisomerase IIb poison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 12168–12173. [Google Scholar]

- Errington, F.; Willmore, E.; Tilby, M.J.; Li, L.; Li, G.; Li, W.; Baguley, B.C.; Austin, C.A. Murine transgenic cells lacking DNA topoisomerase IIb are resistant to acridines and mitoxantrone: Analysis of cytotoxicity and cleavable complex formation. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999, 56, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar]

- Stellrecht, C.M.; Chen, L.S. Transcription inhibition as a therapeutic target for cancer. Cancers 2011, 3, 4170–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Cowell, I.G.; Austin, C.A. Mechanism of Generation of Therapy Related Leukemia in Response to Anti-Topoisomerase II Agents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 2075-2091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9062075

Cowell IG, Austin CA. Mechanism of Generation of Therapy Related Leukemia in Response to Anti-Topoisomerase II Agents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2012; 9(6):2075-2091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9062075

Chicago/Turabian StyleCowell, Ian G., and Caroline A. Austin. 2012. "Mechanism of Generation of Therapy Related Leukemia in Response to Anti-Topoisomerase II Agents" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9, no. 6: 2075-2091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9062075

APA StyleCowell, I. G., & Austin, C. A. (2012). Mechanism of Generation of Therapy Related Leukemia in Response to Anti-Topoisomerase II Agents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(6), 2075-2091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9062075