Identifying the Drivers of Wind Capacity Additions: The Case of Spain. A Multiequational Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background and Literature Review

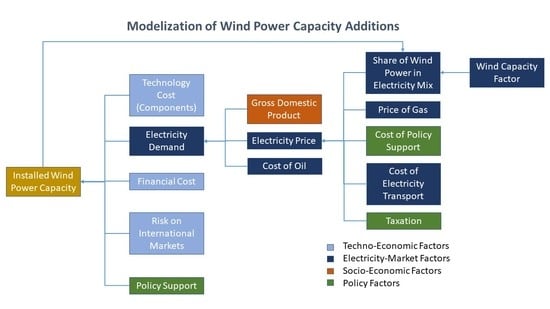

3. Analytical Framework: Drivers and Barriers of Wind Capacity Additions

3.1. Degree of Policy Support

3.2. Technology Costs

3.3. Investment Conditions

3.4. Fossil Fuel Prices

3.5. Merit Order

4. Methods

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century. Renewables 2018 Global Status Report; REN21: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fouquet, R. The Slow Search for Solutions: Lessons from Historical Energy Transitions by Sector and Service. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 6586–6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grübler, A.; Nakićenović, N.; Victor, D.G. Dynamics of Energy Technologies and Global Change. Energy Policy 1999, 27, 247–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, G.J.; Haigh, M. No quick switch to low-carbon energy. Nature 2009, 462, 5682009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowall, W.; Ekins, P.; Radošević, S.; Zhang, L.-Y. The development of wind power in China, Europe and the USA: How have policies and innovation system activities co-evolved? Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2013, 25, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, S.O.; Alkemade, F.; Hekkert, M.P. Why does renewable energy diffuse so slowly? A review of innovation system problems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3836–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenberg, N. Perspectives on Technology; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- International Renewable Energy Agency. Renewable Capacity Statistics; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. Energy Technology Perspectives; IEA: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carley, S. State Renewable Energy Electricity Policies: An Empirical Evaluation of Effectiveness. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 3071–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, D.; Hascic, I.; Medhi, N. Technology and the Diffusion of Renewable Energy. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 648–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, P.; Tarancón, M.A. Analysing the Determinants of On-Shore Wind Capacity Additions in the EU: An Econometric Study. Appl. Energy 2012, 95, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, M.; Ibikunle, G. Determinants of Renewable Energy Growth: A Global Sample Analysis. Energy Policy 2014, 69, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.G. Feed-in Tariff vs. Renewable Portfolio Standard: An Empirical Test of Their Relative Effectiveness in Promoting Wind Capacity Development. Energy Policy 2012, 42, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.C.; Fuinhas, J.A.; Pires Manso, J.R. Motivations Driving Renewable Energy in European Countries: A Panel Data Approach. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 6877–6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Heo, E.; Kim, Y. Dynamic Policy Impacts on a Technological-Change System of Renewable Energy: An Empirical Analysis. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 66, 205–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menz, F.C.; Vachon, S. The Effectiveness of Different Policy Regimes for Promoting Wind Power: Experiences from the States. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1786–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-Y.; Yan, H.; Zuo, J.; Tian, Y.-X.; Zillante, G. A Critical Review of Factors Affecting the Wind Power Generation Industry in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 19, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, P.; Mir-Artigues, P. The Economics and Policy of Solar Photovoltaic Generation, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kilinc-Ata, N. The Evaluation of Renewable Energy Policies across EU Countries and US States: An Econometric Approach. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2016, 31, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, P.; Mir-Artigues, P. Support for Solar PV Deployment in Spain: Some Policy Lessons. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 5557–5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Sawin, J.L.; Pokharel, G.R.; Kammen, D.; Wang, Z.; Fifi ta, S.; Jaccard, M.; Langniss, O.; Lucas, H.; Nadai, A.; et al. Financing and Implementation. In IPCC Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation; Edenhofer, O., Pichs-Madruga, R., Sokona, Y., Seyboth, K., Matschoss, P., Kadner, S., Zwickel, T., Eickemeier, P., Hansen, G., Schlömer, S., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dinica, V. Support Systems for the Diffusion of Renewable Energy Technologies—An Investor Perspective. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, R.; Panzer, C.; Resch, G.; Ragwitz, M.; Reece, G.; Held, A. A Historical Review of Promotion Strategies for Electricity from Renewable Energy Sources in EU Countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1003–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Wind Energy Association. The Economics of Wind Energy; EWEA: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mone, C.; Stehly, T.; Maples, B.; Settle, E. 2014 Cost of Wind Energy Review; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Denver West Parkway Golden, CO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Breeze, P. Power Generation Technologies, 2nd ed.; Newnes; Elsevier Ltd.: Newnes, New South Wales, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wiser, R.; Bolinger, M. 2015 Wind Technologies Market Report; U.S. Department of Energy (DOE): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2015.

- Lantz, E.; Wiser, R.; Hand, M. IEA Wind Task 26: The Past and Future Cost of Wind Energy; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Denver West Parkway Golden, CO, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, N.; Haščič, I.; Popp, D. Renewable Energy Policies and Technological Innovation: Evidence Based on Patent Counts. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2010, 45, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.H.; Huang, C.M.; Lee, M.C. Threshold Effect of the Economic Growth Rate on the Renewable Energy Development from a Change in Energy Price: Evidence from OECD Countries. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 5796–5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appunn, K. Setting the Power Price: The Merit Order Effect. Clean Energy Wire Factsheet. 2015. Available online: https://www.cleanenergywire.org/factsheets/setting-power-price-merit-order-effect#dossier-References (accessed on 9 July 2018).

- Piria, R.; Lorenzoni, A.; Mitchell, C.; Timpe, C.; Klessmann, C.; Resch, G.; Groscurth, H.; Neuhoff, K.; Ragwitz, M.; del Río, P.; et al. Ensuring Renewable Electricity Investments; 14 Policy Principles for a Post-2020 Perspective. Available online: http://remunerating-res.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/14principlespost2020.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2018).

- Boßmann, T.; Sonja Föster, L.J.; del Río, P. Appropriate Policy Portfolios for (Nearly) Mature RES Technologies (Report D3.2.1). In the European Intelligent Energy-Europe Project Towards 2030-Dialogue, European Commission and Executive Agency for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (EASME). 2016. Available online: http://towards2030.eu/sites/default/files/Appropriate policy portfolios for (nearly) mature RES-E technologies.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2018).

- Marques, A.C.; Fuinhas, J.A. Are Public Policies towards Renewables Successful? Evidence from European Countries. Renew. Energy 2012, 44, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red Eléctrica de España. El Sistema Eléctrico Español-Avance 2017; Red Eléctrica de España: Alcobendas, Madrid, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The Statistical Office of the European Union (EUROSTAT). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 7 November 2016).

- The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Available online: https://www.irena.org/Statistics/View-Data-by-Topic/Capacity-and-Generation/Query-Tool (accessed on 7 November 2016).

- Quandl Inc. Available online: https://www.quandl.com/data/ODA/PIORECR_USD-Iron-Ore-Price (accessed on 7 November 2016).

- The Annual Macro-Economic Database of the European Commission (AMECO). Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/ameco/user/serie/SelectSerie.cfm (accessed on 7 November 2016).

- BP plc. Available online: https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy/downloads.html (accessed on 7 November 2016).

- The International Energy Agency (IEA). Available online: https://www.iea.org/statistics/ (accessed on 7 November 2016).

- The National Commission on Markets and Competition (CNMC). Available online: http://data.cnmc.es/datagraph/ (accessed on 7 November 2016).

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow Essex, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Intrilligator, M.D.; Bodkin, R.G.; Hsiao, C. Econometric Models, Techniques and Applications, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman, J.A. Specification Tests in Econometrics. Econometrica 1978, 46, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henningsen, A.; Hamman, J.D. Systemfit: A Package for Estimating Systems of Simultaneous Equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 23, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, J.G. Numerical Distribution Functions for Unit Root and Cointegration Tests. J. Appl. Econom. 1996, 11, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Scope (Technological, Temporal, Geographical) | Determinants Included in the Model | Methodology | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | Wind energy. 1998–2003 39 states in the USA. | Wind energy development (dependent variable), renewable portfolio standard (RPS), fuel generation disclosure requirements (FGD), mandatory green power opinion (MGPO), public benefits funds (PBF), retail choice (RET). | Econometric techniques. Uniequational model. Panel data. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) methods. | Statistically significant: (+) RPS (+) MGPO, (+) RPS experience, (+) MGPO experience, (−) RET experience. |

| [10] | Renewable energy. 1998–2006 50 states of the USA. | RES percentage in electricity generation (dependent variable), total amount of annual RES generation (dependent), RPS policy, state’s environmental policy, number of per capita state and local employees in natural resource governmental positions, percentage of total gross state product (GSP), per capita GSP, growth rate of population, annual amount of total electricity generated divided by the associated state population per year, deregulation, price of electricity, natural resource endowment, subsidy policies index, tax incentive index. | Econometric techniques. Uniequational model. Panel data. Fixed effects (FE) and fixed effects vector decomposition method (FEVD). | RES share: Statistically significant: (+) house score, (+) per capita natural resource employees, (−) petrol/coal manufacturing GSP, (+) GSP per capita, (−) electricity price, (−) electricity use per capita, (+) percent regional RPS, that in both FE and FEVD model; (−) wind and biomass potential, (+) solar potential, (−) tax index, (+) subsidy index, (−) deregulation for FEVD model. Not statistically significant: (−) RPS and growth rate of population. Total RES: Statistically significant: (+) RPS, (+) GSP per capita, (+) percent regional RPS, (−) per capita natural resource employees, (−) wind potential, (+) biomass and solar potential, (−) tax index, (+) subsidy index, (+) deregulation. Not statistically significant: (−) house score for FE, (+) petrol/coal manufacturing GSP, (+) growth rate of population, (+) electricity price, (−) electricity use per capita. |

| [15] | Renewable energy 1990–2006 EU countries. | Contribution of RES to energy supply (dependent variable), CO2 per capita, per capita energy consumption, import dependency of energy, share of coal, oil, gas and nuclear in electricity generation, surface area, coal, natural gas and oil prices, EU’s member in 2001 and real GDP. | Econometric techniques. Uniequational model. Panel data. FE, FEVD and OLS method. | Statistically significant: (−) CO2 emissions, (+) energy per capita, (−) the lobby of coal and oil, (+) energy dependency, (+) income effect for all EU Members, (−) income effect for non-EU Members, (+) oil price and coal price for EU Members, (+) natural gas price for all countries and EU Members, (−) coal price for Non-EU Members, (+) continuous commitment for EU Members and (−) for non-EU Members, (+) geographic area. |

| [11] | Wind, solar photovoltaic, geothermal, biomass and waste. 1990–2004 26 OECD countries. | Investment per capita in capacity of RE (dependent variable), knowledge stock, GDP per capita, % growth of electricity consumption, % electricity production from nuclear and hydro, Kyoto Protocol ratified, natural gas, coal and oil production per capita, % of energy imported, feed-in tariffs, renewable energy certificate and other RES policy. | Econometric techniques. Uniequational model. Panel data. FE method. | The effect of knowledge is significant (+) only for wind and biomass, and it is not influenced by country characteristics. If country fixed effects are considered, then knowledge remains significant in the overall regression. The % of clean substitutes is significant (+) for wind. Ratifying Kyoto is significant (+) for wind and biomass. Individual RES policies are not significant. Ratifying Kyoto has a larger impact on investment than new knowledge. Reducing carbon emissions is the primary driver of RES investments. Natural resources and the % of energy imported by a country are insignificant. |

| [12] | Wind energy. 2006–2008 EU Member States. 23 countries. | Wind capacity additions between 2006 and 2008 (dependent variable), wind resource potentials, support levels, electricity generation costs, type of support scheme, administrative barriers, social acceptance, general investment climate, electricity demand, share of hydro and nuclear in electricity generation, country area, dummy variable that represents minor or major changes in support scheme. | Econometric techniques. Uniequational model. Cross-section data. | Statistically significant: (−) administrative barriers, (−) changes in support scheme, (−) minor changes in support scheme, (+) business competitiveness index, (+) FITs support (only for model 1, i.e. without electricity demand and share of nuclear and hydro). Not statistically significant: (+) level of support, (−) available wind resources, (+) FIT support, (−) social acceptance of wind energy, (+) area, (+) electricity demand, (−) share of nuclear and hydro. |

| [14] | Wind energy. 2005–2009 53 countries. | Total wind installed capacity (dependent variable), feed-in tariff, renewable portfolio standard, interaction of FIT and RPS, gross domestic production per capita, total electricity net consumption, oil imports minus exports, metric tons of carbon dioxide, wind resources, other policies. | Econometric techniques. Uniequational model. Panel data. FE and OLS method. | Results confirm that a FIT is more effective than RPS in promoting wind capacity development. RPS could provide some incentives to developers in the short-term. Deploying wind power is highly responsive to satisfying the electricity demand of this country. The variable CO2 emission is statistically significant. |

| [13] | Renewable energy 1990–2010 38 countries (EU, OECD and five BRICS). | Contribution of RES to energy supply (dependent variable), public policies, ratification of the Kyoto protocol, energy security, CO2 emissions, prices of oil, natural gas, coal and electricity, welfare, contribution of traditional energy sources to electricity generation, energy needs, renewables potential, deregulation of the electricity market, continuous commitment. | Econometric techniques. Uniequational model. Panel data. FEVD and PCSE method. | Statistically significant: (+) CO2 emissions, (−) energy use, (+) Kyoto Protocol, (−) % coal, natural gas and nuclear power in electricity generation, (−) renewable energy potential, (−) industry electricity rates, (+) continuous commitment, (+) biomass and solar potential, (−) fiscal and financial policy variables, (−) voluntary instruments, (+) negotiated agreements. |

| [16] | Solar PV 1992–2007 16 OECD countries Wind power 1991–2006 13 OECD countries | The proportion of patent applications for RE technology to total patent applications (dependent variable for invention model), Installed system cost (dependent variable for innovation model), Cumulative installed capacity (dependent variable por diffusion model). Cumulative installed capacity, market opportunities, domestic and overseas knowledge stock, technology-push policy, market-pull policies, national scientific resources, absorption capacity, public R&D, tariff incentives, RE obligations, environmental taxes, public investment, science resources, raw material prices, coal prices, electricity generation, GDP. | Quantitative. Econometric techniques. Uniequational model. Panel data. 3SLS method. | Policy outcomes create a virtuous cycle in the technological change system through market opportunity, learning-by-searching and learning-by-doing. The static impact of technology-push and tariff incentive policies are effective on invention and renewables obligation and CO2 tax appear to encourage cost reduction in the technologies. When dynamic impacts of policy are considered, FIT appears to outperform renewables obligation policy with very small margin. Dynamic impact of CO2 tax varies with the level of technological development maturity. |

| Type | Factor |

|---|---|

| Technological Factors |

|

| Electricity-Market Factors |

|

| Socio-economic Factors |

|

| Policy Factors |

|

| Variable | Definition | Units | Source | Source (web) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WINDCAP (Dependent variable Equation (1)) | Installed Wind Capacity | MW | EUROSTAT/IRENA | [37,38] |

| Technoeconomic Factors | ||||

| IRON | Iron price | Value (US $ per metric ton) | QUANDL FINANCE | [39] |

| SR | Risk premium ([German long-term interest rate–Spanish long-term interest rate] × 100) | % | AMECO | [40] |

| LTIR | Real long-term interest rates, deflator GDP (ILRV) | % | AMECO | [40] |

| Electricity-Market Factors | ||||

| BRENT | Europe Brent Spot Price FOB | US $ per barrel | BP | [41] |

| ELECON (Dependent variable Equation (2)) | Final domestic consumption of electricity | Mtoe | EUROSTAT | [37] |

| PRICEL (Dependent variable Equation (3)) | Price of electricity for domestic final consumption (2500–5000 KWh). Taxes included. | Euro/kWh | IEA, EUROSTAT and own elaboration | [42,37] |

| PRIGAS | Price of natural gas | US$ per million Btu | BP | [41] |

| SHAREWIND (Dependent variable Equation (4)) | Share of electricity production from wind power | % | EUROSTAT and own elaboration | [37] |

| WINDLOAD | Wind annual average capacity factor | % | EUROSTAT | [37] |

| TRANS_TWH | Transport costs | Mill €/TWh | CNMC | [43] |

| Socio-Economic Factors | ||||

| GDP | Gross domestic product (constant 2010) | Mrd Euro | AMECO | [40] |

| Policy Factors | ||||

| PREMIUMS | FIT or FIP support schemes | Mill € | CNMC | [43] |

| PREM_TWH | Average support for RES | Mill €/TWh | CNMC | [43] |

| TAX_SHARE | Share of taxes on the price of domestic electricity (2500–5000 KWh) | % | EUROSTAT and own elaboration | [37] |

| Equation (1) | Equation (2) | Equation (3) | Equation (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −8.11079 *** | −4.42324 *** | −3.77958 *** | −4.25512 *** |

| ln WINDCAP | Dependent | - | - | 0.86314 *** |

| ln IRON | −0.24103 * | - | - | - |

| ln LTIR | −0.09873 | - | - | - |

| ln ELECON | 4.22806 *** | Dependent | - | - |

| ln SR | −0.09600 | - | - | - |

| ln PREMIUMS | 0.81412 *** | - | - | - |

| ln GDP | - | 1.02037 *** | - | - |

| ln PRICEL | - | −0.08489 ** | Dependent | - |

| ln BRENT | - | 0.04490 * | - | - |

| ln SHAREWIND | - | - | −0.15144 ** | Dependent |

| ln PRIGAS | - | - | 0.05520 | - |

| ln PREM_TWH | - | - | 0.07374 | - |

| ln TRANS_TWH | - | - | 0.84483 *** | - |

| ln TAX_SHARE | - | - | 0.24606 ** | - |

| ln WINDLOAD | - | - | - | 1.15392 *** |

| Adj. R-Squared | 0.9823 | 0.9762 | 0.9496 | 0.9972 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quintana-Rojo, C.; Callejas-Albiñana, F.E.; Tarancón, M.-A.; del Río, P. Identifying the Drivers of Wind Capacity Additions: The Case of Spain. A Multiequational Approach. Energies 2019, 12, 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12101944

Quintana-Rojo C, Callejas-Albiñana FE, Tarancón M-A, del Río P. Identifying the Drivers of Wind Capacity Additions: The Case of Spain. A Multiequational Approach. Energies. 2019; 12(10):1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12101944

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuintana-Rojo, Consolación, Fernando E. Callejas-Albiñana, Miguel-Angel Tarancón, and Pablo del Río. 2019. "Identifying the Drivers of Wind Capacity Additions: The Case of Spain. A Multiequational Approach" Energies 12, no. 10: 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12101944

APA StyleQuintana-Rojo, C., Callejas-Albiñana, F. E., Tarancón, M. -A., & del Río, P. (2019). Identifying the Drivers of Wind Capacity Additions: The Case of Spain. A Multiequational Approach. Energies, 12(10), 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12101944