3.1. LPMSs’ Morphology Characterization with SEM

To choose the correct time of reaction and the quantity of adjuvant, SEM-FEG characterization of samples was performed.

In this work, we started to study the product of the reaction by fixing the surfactant, and using the classical P123

® to synthesize MS [

26,

27]. In

Figure 2, the samples differ in terms of the presence or not of the adjuvant and its amount: in LPMS_1_TMB_18h, the quantity of adjuvant is twice with respect to LPMS_2_TMB_18h, and the difference in the aperture of the structure is noticeable; in LPMS_1_18h and LPMS_2_18h, adjuvant is not present, and the structures are more compact. For these reasons, the presence of an adjuvant was considered necessary, and a ratio by mass 1:3.85 TMB:TEOS was fixed.

Then, maintaining the same ratio by mass of TEOS:surfactant at 1.7:1 and TEOS:TMB at 3.85:1 of the synthesis LPMS_1_TMB_18h, and varying only the time of reaction, we tried to reduce it. It is possible to notice from

Figure 3, starting from 2 h and arriving up to 8 h, that the only result was that the surface became more and more non-homogeneous, but the best time remains at 18 h.

It is possible to notice from

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 that the increasing time brings a better aggregation of the silica nanoparticles and that, at 2 h, they are abundantly present compared to at 18 h, when more sintered structures are present.

After thatwe studied if it was possible to obtain better structures by fixing the time at 8 h, and modifying the ratio by mass TEOS:surfactant from 1:1.0 to 1:2.0.

It is possible to see from

Figure 4 that an increase in the quantity of surfactant causes an increase in pores’ dimensions, which was the intended purpose. For this reason, the ratio by mass of TEOS:surfactant was fixed to 1:2.

It is clear that 18 h of MW treatment seems to be better to obtain the desired structure, but for studying reasons, we decide to also perform studies on samples obtained with 8 h thermal treatment.

At this point, a new surfactant was studied. Pluronic

® F127 was considered, thanks to its polyethyleneoxy chain that is five times longer with respect to P123 [

28].

Taking into account the previous considerations, a new synthesis was identified: LPMS_7_TMB_18h in which the ratio by mass of TEOS:surfactant was fixed at 1:2 and the ratio by mass of TEOS:TMB was fixed to 3.85:1 with the time of reaction at 18 h.

In

Figure 5, is possible to evaluate the difference between LPMS_7_TMB_18h and an equivalent synthesis, LPMS_6_TMB_18h, in which the only difference stays in the surfactant used, which in the second case was P123.

With F127, a great enhancement in the morphology of the structure was obtained: silica nanoparticles were well-sintered and a more open structure and bigger mesopores were obtained. For these reasons, the second surfactant, F127, was the right candidate for our purposes and was fixed as the appropriate surfactant for the next steps.

Additionally, with F127, reactions at 8 h and with different ratios by mass were studied, as reported in

Figure 6.

Even with F127, if the ratio by mass between TEOS and the surfactant was changed, a more opened structure was obtained. Additionally, in this case, the ratio of 1:2 was the best.

At this time, as a preliminary analysis, an estimation of pores’ dimension [

29] and a correlation between their dimensions and the quantity of surfactant was performed, considering the reaction conducted at 8 h with ratios by mass of 1:2.0, 1:1.7, 1:1.4 and 1:1.0. Both surfactants were studied, and the obtained results are reported in

Table 2.

From the estimation, a linear relationship (

Figure 7) between pores’ dimensions and the amount of surfactant used in the synthesis, i.e., between pores’ dimensions and the ratio by mass, was observed. Additionally, thanks to the bigger dimensions of F127 in terms of the carbon chain, larger pores were obtained with this surfactant [

30].

For these reasons, to achieve our purposes, the optimal ratio by mass was 1:2.0, and F127 was the appropriate surfactant.

This determination was performed with exploratory purposes, and samples selected for the following studies were completely and properly characterized (see

Section 2: Textural Properties).

To summarize all our findings: the presence of an adjuvant helps to obtain bigger pores, so TMB was necessary; the best structures in terms of compactness were obtained at a higher reaction time; therefore, samples obtained at 8 h and 18 h were considered in the next steps; the best surfactant is the biggest one; consequently, F127 was chosen; at a higher ratio by mass, bigger pores were obtained, and a ratio of 1:2 of TEOS:surfactant was fixed.

Taking into account all these considerations, the samples studied in the next steps will be LPMS_8_TMB_8h and LPMS_7_TMB_18h.

SEM-FEG characterization (

Figure 8) was also performed for structures used as a reference in loading and release tests. Reference structures considered were MS and silica with no mesopores, only containing micropores (without mesoporous silica, WMS).

It is possible to see, that both structures look compact if compared with the same magnification of LPMS_8_TMB_8h or LPMS_7_TMB_18h, respectively, reported in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

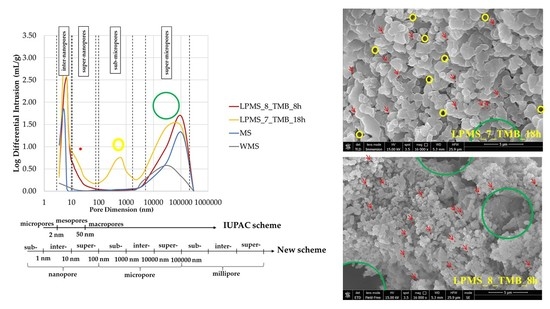

3.2. Textural Properties

N

2 adsorption/desorption and mercury impregnation measurements were performed to evaluate and compare the textural properties of samples, determining the following: specific surface area (SSA

BET), total pore area (A

p) and total intrusion volume (V

p). The first parameter was determined with N

2 adsorption/desorption method as a mean of three different and independent measurements, and the others with mercury impregnation. In

Table 3, the textural parameters of samples are reported. Adsorption/desorption isotherms based on which the surface area values were obtained are presented in

Figure 9. As it is possible to see from

Figure 9, a different behavior between MS and LPMSs is evident: from the dashed lines, the intrusion in pores of big dimensions for LPMSs is noticeable, which is not detectable for MS and WMS.

SSA

BET was not significantly different between samples considered. WMS shows the highest value, due to the presence of micropores that significantly enhance this value. LPMS_8_TMB_8h and LPMS_7_TMB_18h show a value of SSA

BET that is consistent with the values obtained for classical MS [

31]. This behavior can be justified by also considering the other values (A

p and V

p), which are significantly higher for LPMSs with respect to the other structures [

32].

A

p has the lowest values for WMS, which in line with the results considering that the sample only has micropores and the porosimeter cannot measure their pore area; MS, SSA

BET and A

p are comparable, instead of LPMSs that show an SSA

BET lower than the A

p. It can be explained considering that SSA

BET was calculated using N

2 adsorption/desorption and that Ap uses Hg; the latter can fill big pores, instead of N

2, which can only create a layer on the surface of them, so it turns out that A

p can have higher values if compared to SSA

BET [

33].

The mercury impregnation method can determine pores only in the range of 3.5–300 µm.

Figure 10 reports results obtained with the mercury porosimeter, and the classification of pores due to dimensions according to the IUPAC scheme [

34] and a new scheme proposed by T. J. Mays, et al. [

35]. According to particle dimensions, super-micropores can be considered interparticle pores. Pores under 10 µm can be classified, in order of dimensions, as follows: inter-nanopores (1–10 nm), super-nanopores (10–100 nm) and sub-micropores (100–1000 nm). Samples studied in this work present different characteristics in terms of pores, and the type and number of pores present in their structure are summarized in

Table 4.

3.3. Nisin Loading Tests

The efficiency of the loading of a molecule into a structure can be calculated in different ways, using the following: loading efficiency percentage (LE%), loading percentage (Loading%) or loading capacity percentage (LC%).

The loading efficiency percentage (Equation (2)) considers the only amount of Nisin loaded inside the structure as a function of the initial quantity used for loading [

36]:

The initial amount of Nisin was determined directly using a spectrophotometric quantification of the concentration of the loading solution; then, the amount of Nisin loaded can be determined as the difference between the initial concentration and the concentration after loading, which is always determined by spectrophotometric measure.

The loading percentage (Equation (3)) considers the amount of Nisin loaded as a function of the total weight of the loaded structure [

37]:

Loading% can be also calculated, to compare results, using the EA results as follows (Equation (4)):

Finally, the loading capacity percentage was calculated as a function of the amount of Nisin per milligrams of silica (Equation (5)) [

38,

39]:

EA was performed on solids collected after loading and dried overnight. In

Table 5, the EA and samples are reported and were labeled as “sample_name_x” in which x indicates the concentration of Nisin (in mg/mL) in the loading solution.

EA results were used to calculate loading% and to evaluate the stability of Nisin loaded into the structures. As it is possible to see from

Table 4 that the results are in accordance with the concentration of the loading solution: the higher the concentration, the higher the percentage of each element in the structures.

To evaluate the presence of Nisin on the surface of the structures, %N vs. %C obtained with EA were plotted for all samples (

Figure 11), and the slope of linear regression obtained was compared to the ratio %N/%C calculated for pure Nisin. Considering the Nisin molecular formula (C

143H

230N

42O

37S

7), a %N/%C of 0.343 is obtained, which is perfectly in line with the result if compared to the 0.333 obtained with experimental linear regression. For this reason, it can be confirmed that the loaded Nisin is still present, but to assert the presence of non-degraded Nisin and also confirm its presence in the structures after various weeks, a UV-Vis determination is necessary. This aspect will be treated in

Section 4: Results and Discussion.

Comparing LE%, LC% and loading% reported in

Table 6 and in

Figure 12, it could be noticed that the LE% for LPMS_8_TMB_8h and LPMS_7_TMB_18h does not vary significantly at the different loading concentrations and always stays in a range between 50 and 90%, instead of MS, which shows a LE% in the range 20–30%, which is significantly lower than LPMSs; WMS has a LE% that varies exponentially, synonymous with a process under precipitation control. The same results were obtained for Loading%. These effects are caused by the dimensions of pores: for LPMSs, Nisin can fill very large cavities, and the trapped amount is up to 3/4 times higher with respect to classical structures; in MS and WMS, Nisin can stay only on the surface, and the Nisin amount detected is the Nisin precipitated on the surface. This way of loading will bring very fast and not controlled releases, if compared to LPMSs. LC% has, for all samples, an exponential behavior because the more Nisin in the solution, there is more quantity that can be trapped or that can recover the surface.

The Loading% values calculated with EA results are consistent with the ones calculated spectrophotometrically.

TGA-DTA was performed on structures with a comparable LC%, to obtain a decomposition of Nisin in the same mass range, i.e., LPMS_8_TMB_8h_1.35, LPMS_7_TMB_18h_1.35, MS_1.35 and WMS_5.

TGA (

Figure 13) confirmed the results obtained with the previous analysis, and the loss in mass obtained with thermal analysis is comparable to the amount of Nisin established with EA and UV-VIS determination (

Table 7). To determine the loss in mass of loaded structures, unprocessed samples were also analyzed as a blank reference. From the TG derivative graph (DTG) (

Figure 14), a delay in decomposition, with respect to pure Nisin, was observed for all samples, probably caused by the interaction between Nisin and the silica surface. The same derivative shapes of a sample of pure Nisin were obtained, confirming the presence and stability of Nisin loaded onto the structures. In the derivative graph, the first peak at 300 °C is attributable to the pyrolysis of Nisin (*), and the second one (**) at about 480 °C is attributable to the decomposition of the peptide structure [

40].

BET was determined for all loaded samples to evaluate the behavior of LPMS and MS. From SSA

BET values plotted as a function of LC% (

Figure 15), it is possible to see that LPMSs show a lower decrease in SSA if compared to MS; considering the difference in LE% between samples, this behavior could be explained considering first the filling of pores and then, at high concentration, the covering of the surface for LPMSs that permit the slowest decrease of SSA

BET, instead of MS, which undergoes a pore blocking [

41,

42], which is well-known for mesoporous materials. Additionally, superficial analysis confirms the different behavior between WMS and other samples.

3.4. Nisin Release Tests

To evaluate Nisin stability, Nisin release tests were performed on loaded structures a few weeks after loadings. The Nisin content obtained spectrophotometrically and with EA is comparable, so can be asserted that Nisin is present and stable.

Nisin release tests were performed for structures with a comparable Loading%, i.e., LPMS_8_TMB_8h_5, LPMS_7_TMB_18h_5, MS_10 and WMS_10, which all have a Loading% of about 15%.

The amount of Nisin released was determined as % of release (Equation (5)):

Starting from samples with the same Nisin content, a four time longer release and controlled mechanism of release can be achieved for LPMSs (

Figure 16). MS exhibits a shorter release, and even shorter for WMS, of about 1 day and 1 h, respectively, in comparison to 4 days of LPMSs. LPMSs’ releases are definitely longer if compared with the time of the release of MS and previous studies [

43]: LPMSs show releases that last 96 h, instead of MS, which shows a four time shorter release of about 24 h (results in line with previous studies).

Another important aspect is the mechanical resistance that LPMS_7_TMB_18h shows after being kept in contact with SBF for a lot of hours. In

Figure 17, we report the SEM-FEG images of unaltered structures, loaded structures and structures after soaking in SBF.

After release, LPMS_7_TMB_18h maintains its structure, synonymous with mechanical resistance; LPMS_8_TMB_8h does not have the same mechanical resistance, synonymous with the fact that a longer thermal treatment is necessary to obtain structures that can resist over time when used as support for drug release. For MS and WMS, after a release of 24 h or 1 h, respectively, the structures are maintained.

CLSM was used to visibly evaluate Nisin loading. In

Figure 18, microscope images obtained for loaded samples and samples after release are reported.

As it is possible to see from a comparison between the first and the second row in

Figure 18, the confocal microscope images confirm the same patterns observed at SEM-FEG: the structure of LPMS_8_TMB_18h is also maintained after loading and the pores are visibly filled with Nisin, LPMS_7_TMB_8h after loading has a more compact structure due to the filling of superficial cavities and MS and WMS pass from a smooth surface to a non-homogeneous surface due to Nisin precipitation on the surface of the microparticles.

The hypothesis of an in-pore drug loading for LPMSs and an external deposition of Nisin for MS and WMS was confirmed.

In fact, loaded structures of MS and WMS show a change in the superficial aspect, indicating that Nisin precipitates on the surface, and for LPMSs, it is noticeable for the filling of pores.

In addition, complete releases can be demonstrated. As it is possible to see from images, the fluorescence of samples is highly quenched, synonymous with an almost complete release.