Legal Harvesting, Sustainable Sourcing and Cascaded Use of Wood for Bioenergy: Their Coverage through Existing Certification Frameworks for Sustainable Forest Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- ■

- Lower quality wood from forestry management, e.g., small trees, stumps, branches and other slash;

- ■

- Sawmill processing or other industrial wood residues, e.g., off-cuts, sawdust, and shavings, and

- ■

- Post-consumer waste wood (or recovered wood), e.g., construction and demolition waste wood.

| Wood pellets | chips | Other residual wood | Low quality round wood ** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possible end uses | Coniferous | Non Coniferous * | (particles, sawdust and post-consumer wood waste) | Fuelwood | Pulpwood | ||

| - Wood based panels | 0 | large share (OSB, MDF) | large share (EU intra trade) | large share (particleboard) | 0 | large share | |

| - Pulp and paper production | 0 | large share (pulp) | large share(EU extra trade) | low share | 0 | large share | |

| - Larger scale power and heating (> 1 MW) | large share (EU extra trade) | growing share | negligible | growing feedstock for pellets | 0 | growing share for pellets | |

| - Small scale heating (< 1 MW) | large share (EU intra trade) | substantial share | some share (birch) | negligible | residential heating | low share (birch, oak and beech) | |

| - Other (e.g. stable litter, etc.) | negligible | 0 | 0 | negligible | 0 | 0 | |

| EU total trade 2012 | 8,297 | 6,288 | 3,436 | 7,339 | 3,853 | 25,495 | |

| -EU extra trade 2012 | 4,491 | 1,768 | 2,528 | 1,813 | 1,579 | 7,665 | |

| -EU intra trade 2012 | 3,807 | 4,521 | 909 | 5,527 | 2,274 | 17,830 | |

| Top 10 of supplier countries for the individual type of biomass source and their market share | |||||||

| 79% | 78% | 82% | 54% | 74% | 73% | ||

| Supplier number 1 | United States | Russia | Uruguay | Netherlands | UK | Latvia | |

| Supplier number 2 | Canada | Latvia | Chile | United Kingdom | Ukraine | Russia | |

| Supplier number 3 | Latvia | Germany | Russia | Norway | Bosnia Herzogovina | Germany | |

| Supplier number 4 | Russia | Rumania | Croatia | Switzerland | Croatia | Belarus | |

| Supplier number 5 | Germany | Estonia | Latvia | Bosnia Herzogovina | Hungary | Estonia | |

| Supplier number 6 | Estonia | Belarus | Belarus | Russia | Bulgaria | Spain | |

| Supplier number 7 | Portugal | Austria | Liberia | Belgium | Slovenia | Poland | |

| Supplier number 8 | Austria | Poland | Germany | Latvia | Germany | Norway | |

| Supplier number 9 | Ukraine | Finland | Estonia | Slovenia | Norway | France | |

| Supplier number 10 | Rumania | Belgium | Brazil | Austria | Latvia | Portugal | |

2. Overview of Developments Regarding Sustainable Woody Biomass Trade

2.1. SFM Schemes in North America (Supply Side)

2.2. Evolving Public and Private Strategies in the EU for Sustainable Biomass (Demand Side)

| Region | Total Forest Area(in Million ha) | Managed Forests *(in Million ha) | Change in Total Forest Area 2000–2010 (in %) | Certified Forests ofFSC per February 2014 in Million ha [56] | FSC forest Areas in % of Managed Forests | Certified Forests of PEFC per March 2013, in Million ha [57] | PEFC Forest Areas in % of Managed Forests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 674.4 | 186.0 | −0.49 | 6.7 | 4% | 0 | 0% |

| Asia and the Pacific | 740.4 | 230.5 | 0.19 | 11.4 | 5% | 14.6 | 6% |

| Europe | 1005 | 844.2 | 0.07 | 80.0 | 9% | 77 | 9% |

| - Russia | 809.1 | 703.9 | - | 38.7 | 5% | 0.5 | 0% |

| - EU-28 | 130.4 | 99.1 | - | 31.7 | 32% | 67.9 | 69% |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 890.8 | 83.4 | −0.46 | 14.1 | 17% | 3.2 | 4% |

| The Near East | 122.3 | 46.3 | 0.07 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| North America | 679.0 | 554.0 | 0.03 | 69.1 | 12% | 149 | 27% |

| - Canada | 310.1 | 294.6 | 0 | 54.43 | 18% | 113.5 | 39% |

| - USA | 304.0 | 228.0 | 0.13 | 14.1 | 6% | 35.3 | 15% |

2.2.1. National Policy Schemes on Sustainability of Solid Biomass

2.2.2. Private Certification Schemes by the Energy Sector

2.3. Industrial Wood Processing Residues versus Post-Consumer Wood Waste

3. Methodological Framework

3.1. Legal Harvesting: EU Timber Regulation (2010/995/EC)

3.2. Sustainable Sourcing: EU’s 2010 Communications

3.3. Cascaded Use: EU’s Waste Directive (2008/98/EC)

3.4. Benchmark Compilation

- A

- “Greenhouse gas (GHG) calculations” for activities in the solid biomass supply chain. This aspect is also incorporated in the RED for liquid biofuels [1]. In our benchmark we have limited it to GHG effects from forest operations, due to the forest management scope in the SFM frameworks.

- B

- “Safeguard of forests with high biodiversity. This no-go area is also incorporated in the RED for liquid biofuels [1]. Specifically, we have inventoried the protection of primary forest areas, along with specific safeguards for the sensitive undisturbed forest areas in North America, called old growth forest or intact forest landscapes. Other areas designated by law for nature or environmental protection purposes [32] are not regarded in our benchmark.

- C

- “Safeguard of forests with high carbon stocks and areas such as wetlands and peat lands”. These no-go areas are also incorporated in the RED for liquid biofuels [1].

- D

- “Sustainable harvest rates” (or maximum levels for annual allowable cuts). We focus on intensive harvesting practices, as EC’s 2010 Communications state that a number of other practices can result in a significant loss of both terrestrial carbon and significant changes in productivity. Examples are harvesting practices that result in excessive removal of litter or stumps from the forests [18]. Next the final harvest conditions are relevant: large felling areas, without adequate provisions for regeneration, often remain understocked (less carbon) after clear-cutting [88]. Therefore the clear-cutting area is also considered in our inventory.

- E

- “Preventing deforestation”, with a focus on forest management plans and post-harvest guidelines that include regeneration and replanting practices. EC’s 2010 Communications also state that deforestation and forest degradation can result in a significant loss of both terrestrial carbon and significant changes in productivity. Indirect land use change (iLUC) effects are not included: its quantitative evaluation is difficult and there is not yet any scientific consensus [89,90,91,92,93

- F

- “Exceptional removal of dying or dead trees”, related to both managed and non-managed forests. Sustainable harvest rates (see criterion D) are elaborated for the long term, in which exceptional circumstances are not accounted for. Therefore, we added the exceptional removal of dead or dying trees after natural disturbances (criterion F); these so called “salvage logging” operations may affect both biodiversity and carbon stocks [22,26].

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- CSA Z809 [100];

- 5

- ATFS 2010–2015 [101]. We added ATFS as another option (“miscellaneous”). It is not included in the UK scheme as Evidence A, but this FM option is currently used for international biomass trade under the GGL umbrella. It had a 4.5% share in the GGL trade in 2012 (see Appendix C). ATFS usually certifies wood plantations, whereas our sustainability benchmark is applied to all forest types;

- 6

- WWF Gold Standard [102]. In addition, for a few of the criteria, the WWF-GS) is also evaluated as “miscellaneous”. In 2013, WWF enlarged its international GS program with CarbonFix projects, those are certified forest plantations in combination with carbon credits.

- 7

- 8

- PEFC Due Diligence (PEFC-DD) [72];

- 9

- SFI Procurement, also called SFI fiber sourcing (SFI-FS), and limited to SFI Objectives 8–20 [42].

4. Benchmark Results

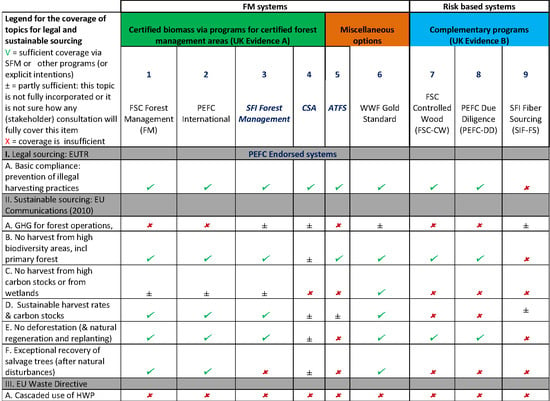

| FM systems | Risk based systems | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certified biomass via programs for certified forest management areas (UK Evidence A) | Miscellaneous options | Complementary programs (UK Evidence B) | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| FSC Forest Management | PEFC International | PEFC Endorsed Forest Management frameworks | WWF Gold | FSC CW | PEFC DD | SFI FS | |||

| forest | SFI forest | CSA | ATFS | Standard | Controlled | Due | Fiber sourcing | ||

| management | management | (complementary to FSC FM) | Wood | Diligence | (wood | ||||

| procurement) | |||||||||

| I. Legal sourcing: EU Timber Regulation (EUTR) | |||||||||

| A. Basic compliance: prevention of illegal harvesting practices | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | X |

| II. Sustainable sourcing: EU Communications (2010) | |||||||||

| A. GHG for forest operations, anticipating a GHG savings requirement | X | X | ± | ± | X | ± | X | X | ± |

| B. No harvest from high biodiversity areas, incl. primary forest | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | ± | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | X |

| C. No harvest from high carbon stocks or from wetlands | ± | ± | ± | X | X | Ѵ | X | X | X |

| D. Sustainable harvest rates and carbon stocks | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | ± | ± | Ѵ | X | X | ± |

| E. No deforestation (and natural regeneration and replanting practices) | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | ± | X | Ѵ | Ѵ | Ѵ | X |

| F. Exceptional recovery of salvage trees (after natural disturbances) | Ѵ | Ѵ | X | ± | X | Ѵ | X | X | X |

| III. EU Waste Directive (post-consumer waste) | |||||||||

| A. Cascaded use of harvested wood products | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Legend for the coverage of topics for legal and sustainable sourcing | |||||||||

= sufficient coverage via SFM or other programs (or explicit intentions) = sufficient coverage via SFM or other programs (or explicit intentions) | |||||||||

| ± = partly sufficient: this topic is not fully incorporated or it is not sure how any (stakeholder) consultation will fully cover this item | |||||||||

= coverage is insufficient = coverage is insufficient | |||||||||

5. Discussion

5.1. Mass Balance Approach

- √

- The main Evidence A type accepted for compliance with UK’s draft law should be the approved forest management (FM) schemes of FSC or PEFC International endorsed schemes. Therefore, far, two PEFC endorsed schemes in North America are allowed by the UK: CSA and SFI FM [32,33]. The compliance with the EU’s draft legislation is sufficient for FSC-FM and SFI-FM, except for prevention of sourcing biomass from wetlands. In particular, CSA lacks sufficient guidance for this topic, and unwanted biomass sourcing may occur. Further, the topic of salvage logging is not yet embedded in SFI’s forest management, which can lead to possible excessive recovery of dead trees, instead of leaving them as a key biotope for wildlife. Finally, ATFS (a PEFC endorsed scheme) is not approved by the UK for Evidence A [33]. Therefore, ATFS fibers cannot actually be regarded as FM certified fibers [108].

- √

- Other Evidence B is allowed, if Evidence A is not available [64]. The information needed for Evidence B to be eligible is indicated in Appendix B, with three draft checklists of information items that should be made available regarding legality, sustainable sourcing, and supply chain control. The UK suggests FSC’s controlled sources (FSC-CW) and PEFC’s avoidance of controversial sources (PEFC-DD) and SFI-FS. The remaining 30% shares from FSC-CW, PEFC-DD and SFI-FS showed insufficient coverage of EU’s draft legislation on legal harvesting, sustainable sourcing and cascaded use (Table 3). Specifically, the SFI-FS system is a matter of concern. SFI-FS certified woody biomass can consist of high risk fibers (controversial sources), especially when the biomass is sourced from outside North America. Neither of those systems can in itself be accepted for 100% under the UK law. However, they can be partly used; information and evidence B should be provided to demonstrate the wood is legally and sustainably sourced and traceability documents are met [64].

- A

- Current situation. Following Section 2.2.2, individual certification or verification systems exist per energy company: Laborelec, Drax’ and GGL procedures. For example, GGL accepts different SFM certificates. Some of those certificates can be regarded as insufficient to comply with current EU’s (draft) legislation in our benchmark (Section 4). When the companies purchase their pellets from the same supplier and (unintentionally) claim the same part of sustainable fiber input and output (via an independent mass balance check), there is no safeguard to prevent the remaining share of non-suitable fibers (either non-approved fibers or abundant risk-based fibers) from flowing into the EU market. Actually, the mass balance becomes a less suitable tool, in case all EU’s (draft) legislation for legal harvesting and sustainable sourcing has to be fully complied with. If full compliance with this legislation is required, we think it is crucial to have one cross-reference procedure in place by certification bodies (see further the Recommendation Section).

- B

- Near future situation (2015 onwards). UK’s requires to have minimum 70% Evidence A and maximum 30% Evidence B certificates at the final end of the supply chain, when biomass is delivered to the site of an energy plant. The UK requirements will start in 2015. This approach was already initiated by the main SFM programs, after immediate action was required after the launch of the EUTR for legal sourcing in 2013 and there were not enough FM fibers available on the market. A large share of managed (production) forest areas is currently not certified; the risk approach is used by suppliers to comply with legal sourcing requirements (EUTR, Lacey Act) to a maximum of 30%, in line with common used certified SFM labels as “FSC Mix 70%” [71] and “PEFC certified” [109]. Both labels allow mixed fiber contents in wood products for marketing purposes, when at least 70% of the fibers originate from certified forest areas. Following UK practices, the EU could also impose maximum shares of risk based fibers in other Member States with SFM certificates when the compliance of woody biomass for energy is insufficiently in agreement with EU’s sustainability goals.

- C

- Long term future situation. Currently, risk based assessments are preferred as the costs for such a program are less expensive than the implementation of one in which all forests are certified (FM fibers). We think that in the long term, a considerably larger forest area can be certified, only when more financial means are available and the certification of small private forest areas is facilitated via group certification or otherwise. If so, the risk based assessments and also an extra cross-reference check in case of individual mass balances (situation A), would become less important.

5.2. Adaptation of Forest Legislation and Voluntary Forest Certification to Future Needs

5.3. Forest Carbon and GHG Accounting Approach

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- ■

- Mass balance. In the case of different private sustainability schemes, there is a risk that abundant shares of risk based fibers or remaining non-approved fibers will unintentionally flow into the EU market. We think it is crucial to have a cross-reference procedure in place to reach 100% compliance with the EU’s (draft) legislation for legal harvesting and sustainable sourcing. We suggest one overarching mass balance between certification bodies per individual pellet plant, storage unit, or per aggregated group of plants (juridical entity) to verify the certification status of fibers for the EU energy markets. The completion of the SBP by EU’s energy sector may help to address this topic.

- ■

- Ceiling risk based fibers. Currently, there are not enough FM certified fibers, while at the same time the EUTR and the US Lacey Act ask for compliance with their legal harvesting requirements. Risk based fibers from less stringent risk assessments can comply with these basic requirements. However, from the perspective of more stringent sustainable sourcing, a limited use (ceiling) of risk-based biomass is preferred. It is recommended to have a debate on the EU level, to which extent the use of risk based fibers should be allowed and for which period, combined with the current state-of-the-art certification and the short term availability of the preferred, certified FM fibers. For example, the UK has selected a 30% ceiling for the use of risk based wood chips, wood pellets etc. by the UK energy plants, starting from 2015. All kinds of certified fibers will be evaluated via mass balances per actor in the supply chain; a remaining share of non-approved fibers is not allowed.

- ■

- Mutual recognition. FSC-CW products exclude the fibers from PEFC certified products, largely due to differences in the risk based fibers [39]. The compatibility of SFM certificates can be improved, when a mutually recognized assurance system is introduced. As a spin off, full mixing of FSC and PEFC fiber flows results in one uniform mass balance check by the forest and energy sector.

- ■

- Group certification. For individual forest owners, it is costly to reach FM certification for relatively small forest areas, which practically limits the intake of FM certified fiber supplies. The EU promise to facilitate certification of small forest holdings (Section 3.2) is also of interest for owners supplying biomass for energy, for example in Latvia and Portugal, where few smallholders are now certified.

- ■

- Track and tracing. Further investigation is needed to verify whether the North American upstream supply monitoring of risk based fibers by SFI-FS back to the state level is appropriate in comparison with the EU’s prescribed approach to track and trace risk based fibers back to a detailed FMU level.

- ■

- Vulnerable forest areas. Further consensus amongst stakeholders in the EU and on a broader international level is needed on definitions of primary forests and high carbon stock areas. In general, current SFM certification schemes hardly cover the protection of carbon rich forests from possible unstainable harvesting practices. Private certification initiatives for wood product and biomass sourcing may extend their schemes with criteria for “leakage” (external GHG effects), as applicable for forest projects in WWF’s GS [102]. This helps to address the vulnerable areas in or nearby FMU’s.

- ■

- Preliminary restrictions. In the meantime, vulnerable high biodiversity forest areas should be excluded from biomass sourcing, unless evidence is provided that harvesting is not harmful. Together with exclusion of vulnerable areas, site-specific measures and obligatory indicators should be developed for the newest harvesting practices (e.g. slash recovery techniques in Scandinavia) and also exceptional tree removals after a natural hazard (e.g. salvage logging in North America).

- ■

- Carbon accounting. It is desirable that countries implement a full carbon accounting system that covers forest carbon pools and their stock changes (flows) in time and space. The UNFCCC umbrella for national forest carbon reporting [116] is a good example of how to complete carbon accounting at national levels, and a possible solution to deal with all types of carbon impacts in time. If applied by all wood producing and trading countries around the world, sustainable carbon stocks in managed forests can be sufficiently monitored via the national GHG reports. As a best practice example, the international methods of immediate GHG emissions from harvesting of forest biomass for energy and of delayed GHG emissions for HWP can be implemented on a country level [84]. Any other method of forest biomass harvesting (e.g. ‘carbon debt’ in time, depending on forest stand type, etc.) needs further guidance and should a priori not lead to complex bookkeeping methods. Although the intentions were to appropriately account for carbon in time and the right place, past experience with carbon accounting for afforestation and reforestation (AR projects) under the Kyoto Protocol has shown that the issue of temporary forest carbon credits was made rather complex.

- ■

- EU Waste Directive. The recycling of waste fibers into other products is prioritized in the EU Waste Directive (cascading), when those processes have no adverse environmental or human health impacts. Recycling of waste wood in pellets is not yet practiced, due to unclear rules in the EU Waste Directive about overseas shipping (Section 3.3). Ideally, the trade of wood pellets from clean wood waste should be facilitated with less administrative barriers for the import by the EU, in order to have this new option seriously accounted for as a future resource for energy.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflict of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| ATFS | American Tree Farm System |

| BC | British Columbia |

| BHG | Biomass Harvesting Guidelines |

| BMP | Best Management Practices |

| CB | Certifying Body (as officially accredited by SFM frameworks) |

| CITES | Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of wild fauna and flora |

| COC | Chain of custody (terminology used by certifiers for downstream wood supplies) |

| CPET | Central Point of Expertise on Timber procurement |

| CSA | Canadian standards association (in our benchmark related to forest management standards) |

| CU | Control Union Certifications (Certifications Body) |

| DDS | due diligence system (terminology for framework set up for compliance with EUTR) |

| EC | European Commission |

| EUTR | European Union Timber Regulation (2010/995/EC) |

| EU-28 | Member States of the European Union since January 2013, when Croatia joined the EU. |

| FM | forest management (used for sustainability standards related to the certifying forest areas) |

| FMU | forest management unit, more or less equal to DFA defined forest area |

| FSC | FM Forest Stewardship Council—forest management |

| FSC | CW FSC: Controlled wood (certificate related to fibers from non-certified forest areas) |

| GEC | Gross Energy Consumption |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GGL | Green Gold Label (standard set up by the energy sector for sustainable biomass sourcing) |

| HCV | high conservation area |

| iLUC | indirect land use change |

| KP | Kyoto Protocol |

| MO | Monitoring Organisation (on behalf of the EUTR) |

| MPB | mountain pine beetle |

| NGO | Non—governmental Organisation |

| PEFC | FM Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (see also FM) |

| PEFC | DD Due Diligence part of PEFC standard, related to fibers from non-certified forest areas) |

| RED | Renewable Energy Directive (2009/28/EC) |

| SBP | Sustainable Biomass Partnership (formerly Initiative Wood Pellet Buyers or IWPB) |

| SFI | FM Sustainable Forestry Initiative (related to Forest Management) |

| SFI | FS Idem, but related to the Fiber Sourcing part only |

| SFM | Sustainable forest management (overall programme for FM and Chain of custody criteria) |

| SGS | Société Générale de Surveillance (Certification Body) |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework on Climate Change Convention |

| US | United States |

| VPA | Voluntary Partnership Agreement (related to Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade) |

Appendix A. Overview of Potential Wood Flows for Bioenergy in the EU-28 [117]

- ■

- Residential heating. The majority of EU’s woody biomass consumption is related to households, i.e., residential heating: about 91 million dry tonnes. About 77% of this is supplied via fuel wood (low quality logs) from the forests. The remaining feedstock is supplied by wood pellets and post-consumer wood waste [120].

- ■

- Industrial heating and power. According to Mantau [120], the energy sector consumed about 44 dry million tonnes of woody biomass for power and heating. The feedstock consisted of about 49% of low quality pulpwood or fuelwood, 35% of wood chips (including other residues like bark and sawdust), 13% of post-consumer wood waste and 3% of wood pellets. EU’s forest industries consumed about 14 million dry tonnes of low quality wood and 32 million tonnes of pulp waste for their internal energy needs.

- ■

- Pulp production. According to CEPI’s division for the pulp and paper sector in the EU-28 plus Norway [121], the pulp sector used 26% wood chips and 74% pulpwood for the production of pulp in 2010. This pulp is used for paper production in a next stage, together with waste paper.

- ■

- Panel boards. According to a detailed division by the European Panel board Federation (EPF) [122], OSB mills (with about 3 million tonnes of woody feedstock), MDF plants (9.5 million tonnes) and particle boards manufacturers (19.5 million tonnes) use on average 40% pulpwood, 43% industrial residues (chips and others) and 17% post-consumer wood waste in 2009. This division is similar to that compiled for 2010 [120].

- ■

| Wood pellets | Chips | Other residual wood | Low quality round wood ** | Total input of feedstock | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coniferous | Non Coniferous *) | (particles, sawdust and post | Fuelwood | Pulpwood | ||||

| consumer wood waste) | ||||||||

| 1 | Energy use small scale 2010 [120] | 17% | 0% | 6% | 77% | 0% | 91 million tonne | |

| 2 | Energy use large and medium scale 2010 [120] | (chips including other industrial residues) | (mainly post-consumer wood waste) | 90 million tonne * | ||||

| - CHP's etc energy sector | 3% | 35% | 13% | 49% | 43.9 million tonne | |||

| - CHP's forest industries | 0% | 0% | 4% | 96% | 13.9 million tonne | |||

| - pulp waste (black liquor) | No trade; only internal use within pulp- and paper industries | 32.3 million tonne | ||||||

| 3 | Pulp industry 2012 [121] | 0% | 23% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 76% | 70 million tonne **) |

| 4 | Panelboard industry 2009 [122] | 32 million tonne | ||||||

| - OSB | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | 3 million tonne | |

| - MDF | 0% | 53% | 0% | 0% | 47% | 9.5 million tonne | ||

| - particleboard | 0% | 48%, mainly other industrial residues | 24% post-consumer wood waste | 0% | 28% | 19.5 million tonne | ||

| 5 | Sawmills 2010 [120] | Feedstock not applicable for energy | ||||||

| - sawnwood | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | Only high quality sawlogs | |

| - veneer and plywood | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | Only high quality sawlogs | |

Appendix B. Checklist for Legal and Sustainable Sourcing, in Case of Evidence B

- 1

- Supply chain information

- 2

- Forest source information for legality

- 3

- Forest source information for sustainability

- Supply chain information (chain of custody)The main elements to be provided are:

- ■

- Supply chain description

- ■

- Controls for preventing mixing or substitution.

- ■

- Mechanisms for verification.

- ■

- Which kind of evidence is available or provided.

- Forest source information for legality (legal sourcing)The main elements provided are:

- ■

- The forest owner/manager holds legal use rights to the forest.

- ■

- There is compliance by both the forest management organization and any contractors with local and national laws including those relevant to forest management (FM), environment, labor and welfare, health and safety and other parties’ tenure and use rights.

- ■

- All relevant royalties and taxes are paid.

- ■

- Whether there is compliance with the requirements of CITES.

- Forest source information for sustainability (sustainable sourcing)The main elements provided are:

- ■

- There must be a definition of sustainability based on a widely accepted set of international principles and criteria defining sustainable or responsible forest management (FM) at the forest management unit level (FMU).

- ■

- The process of defining “sustainable” must seek to ensure balanced representation and input from the economic, environmental and social interest categories. (i) No single interest can dominate the process; (ii) No decision can be made in the absence of agreement from the majority of an interest category.

- ■

- Ensure that harm to ecosystems is minimized. In order to achieve this there must be (i) appropriate assessment of impacts and planning to minimize impacts; (ii) protection of soil, water and biodiversity; (iii) controlled and appropriate use of chemicals and use of integrated pest management wherever possible; (iv) proper disposal of wastes to minimize any negative impacts.

- ■

- Seek to ensure that productivity of the forest is maintained. In order to achieve this the definition of sustainable must include requirements for: (i) Management planning and implementation of management activities to avoid significant negative impacts on forest productivity; (ii) Monitoring which is adequate to check compliance with all requirements, together with review and feedback into planning; (iii) Operations and operational procedures which minimize impacts on the range of forest resources and services; (iv) Adequate training of all personnel, both employees and contractors; (v) Harvest levels that do not exceed the long-term production capacity of the forest, based on adequate inventory and growth and yield data.

- ■

- Seek to ensure that forest ecosystem health and vitality is maintained. In order to achieve this the definition of sustainable must include requirements for: (i) Management planning which aims to maintain or increase the health and vitality of forest ecosystems; (ii) Management of natural processes, fires, pests and diseases; (iii) Adequate protection of the forest from unauthorized activities such as illegal logging, mining and encroachment.

- ■

- Seek to ensure that biodiversity is maintained. To achieve this, the definition of sustainable must include requirements for: (i) Implementation of safeguards to protect rare, threatened and endangered species; (ii) The conservation/set-aside of key ecosystems or habitats in their natural state; (iii) The protection of features and species of outstanding or exceptional value.

- ■

- Legal, customary and traditional tenure and use of rights of indigenous peoples and local communities related to the forest are identified, documented and respected.

- ■

- Management of the forest must ensure that appropriate mechanisms are in place for resolving grievances and disputes including those relating to tenure and use rights, to forest management practices and to work conditions.

- ■

- Ensure that the basic labor rights of forest workers are safeguarded. In order to do this the standard must include requirements concerning the following: (i) freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining; (ii) the elimination of all forms of compulsory or forced labor; (iii) the effective abolition of child labor; (iv) the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

- ■

- Ensure that appropriate safeguards are put in place to protect the health and safety of forest workers.

Appendix C. One Example of Combining SFM Certification and Sustainable Sourcing

Appendix D. Inventory of Mutual Compliance for Legal and Sustainable Wood Sourcing

D1. Benchmark of FM Frameworks (FM Fibers)

- √

- FSC criterion 1.4. The forest manager shall develop and implement measures—to systematically protect the Management Unit from unauthorized or illegal resource use, settlement etc.

- √

- PEFC COC (applicable for all traded products under PEFC, CSA, SFI or ATFS scope). Criterion 5.6.2. Timber known or reasonably suspected as coming from illegal sources (“controversial sources”) shall not be processed and shall not be traded and/or shall not be placed on the market.

A. GHG Calculation of forest Operations

- ±

- CSA indicator 6.3.4.4 refers to Forest conditions and management activities that contribute to the health of global ecological cycles. Machine operations generate emissions of carbon dioxide and other compounds that contribute to climate change. Thus, the lower that forest managers can make the emissions during forest operations, the better for the environment. Therefore, Carbon emissions of fossil fuels in forest operations are included as a discussion item via an informative annex [124]. As such, this indicator is still subject to further discussion within CSA (see Section 4).

- ±

- SFI shall provide financial support for forest research to improve SFM (measure 15.1). The research shall include some of the following indicators: I. Forest operations efficiencies and economics combined with indicators J. energy efficiency and K. Life cycle assessment. As not all issues need to be included, we regard SFI to have a rather limited coverage.

B. Protection of High Biodiversity Areas, Including Primary Forest Areas

- √

- FSC Principle 9 The maintenance of HCV areas, requires that the forest management shall have the following elements:

- ■

- Assess and record the presence and status of HCV areas in the FMU (Criterion 9.1);

- ■

- Develop and implement effective strategies to maintain or enhance the identified HCV’s (Criteria 9.2 and 9.3) and

- ■

- Demonstrate that periodic monitoring is carried out to assess changes in the status of HCV and adapt its management strategies to ensure their effective protection (Criterion 9.4).

- √

- PEFC International main criterion 4 is dealing with The maintenance, conservation and appropriate enhancement of biological diversity in forest ecosystems. Forest management planning within PEFC shall consist of the following steps:

- ■

- Aim to maintain, conserve and enhance biodiversity on ecosystem, species and genetic levels and, where appropriate, diversity at landscape level (Criterion 5.4.1) and

- ■

- together with inventory and mapping of forest resources, FM planning shall identify, protect, and/or conserve ecologically important forest areas containing significant concentrations of 4 detailed types of biodiversity areas (Criterion 5.4.2). PEFC notes that “This does not necessarily exclude forest management activities that do not damage biodiversity values of those biotopes”. Thus, harvesting of wood is allowed in these areas under certain conditions.

- √

- ATFS has a commitment (Indicator 1.1.2) that management plans must address, amongst others, the following resource elements: threatened and endangered species and HCV forests. In addition, FM activities should maintain or enhance HCV forests (performance measure 5.4). ATFS states for this commitment: Informal assessment of HCV forest occurrence through consultation with experts or review of available and accessible information is appropriate, due to the small scale and low intensity of family forest operations [101]. ATFS has another Indicator (7.1.1) that Forest owners must make a reasonable effort to locate and protect special sites (like unique ecological communities) appropriate for the size of the forest and the scale and intensity of FM activities.

- √

- The SFI program has 4 main objectives related to biological conservation. Objective 1 (FM planning) should include a review of, amongst others, pilot projects and programs to promote biological diversity conservation. Objective 2: Ensure long term conservation of forest resources through soil conservation and other measures. Objective 4: The SFI participants shall support or participate in plans or programs for the conservation of old growth forests in the region of ownership (e.g., Performance Measure 4.2 states: participants shall provide information to the landowners for wildlife and biodiversity, including forests with exceptional conservation value). Objective 11 is related to Conservation of Biological Diversity, Biodiversity Hotspots and High-Biodiversity Wilderness Areas (e.g., Performance Measure 11.1 states Program participants of SFI certified sources shall include efforts to promote conservation of biological biodiversity).

- ±

- CSA participants will have to identify sites of special biological significance within the defined forest area (DFA, similar to FMU) and implement strategies appropriate to their long term maintenance (Element 4.1).However, CSA has earmarked old growth as a discussion item, when it refers to the conservation of old growth forest attributes (e.g., dead trees). We regard this as partially covered, as long as it is not included as a core indicator for the audit process (Section 4).

C. Safeguard of High Carbon Stock Forests (Protected Forest Areas)

- √

- FSC has included this topic in the explanatory notes and rationales; as such it has an informative rather than a prescriptive status. Criterion 9.1 of the notes states that High carbon forests and intact forest landscapes can be classified as high conservation value (HCV) areas. However, to date there is no consensus on how to incorporate this in the FSC principles and criteria.

- √

- PEFC International refers to Forest management practices that shall minimize direct or indirect damage to soil (Criterion 5.1.9) and that Special care shall be given to silvicultural operations on sensitive soils and erosion prone areas. Inappropriate techniques such as deep soil tillage and use of unsuitable machinery shall be avoided in such areas (Criterion 5.5.3). Nevertheless, we regard this topic as partially covered, as the protection of high carbon stocks is not explicitly required.

- √

- The Gold Standard reflects the protection of forests with high carbon stocks: the project area shall not be on ground with permafrost, not be on wetlands, soil disturbance shall be lower than 10% of the total project area and organic soils shall not be drained (Criterion 5.1 Applicability). In addition, the emissions of forest operations (site preparation; fertilization) can be subject to a GS requirement: Criterion 5.4. Other emissions.

- ±

- SFI forest management has an explicit reference to carbon stocks. Indicator 1.1.1 prescribes FM plans to include a review of non-timber issues, amongst them carbon storage and bioenergy feedstock. In addition, performance Measure 3.2 prescribes The identification and protection of non -forested wetlands etc. After screening audit reports on this topic [128], it is not clear if high carbon forest areas are included in the forest audit.

- ➢

- Also CSA has covered the topic of carbon via element 4.1: Maintain the processes that take carbon from the atmosphere and store it in forest ecosystems. Core indicators are net carbon uptake and reforestation success. It is not made clear in the audit reports (public summaries) if and how any possible high carbon storage forest areas are included for protection in the FM [129,130,1

- ➢

- Finally, ATFS has a commitment for practicing sustainable forestry, consisting of the Indicator 1.1.2, which suggests but does not require the plan to address carbon storage where present and relevant [134]. In addition, the FM plan has wetlands included as optional: If they are present and desired by the forest owner. Thus, protection of high carbon stocks is not obligatory for the ATFS check.

D. Sustainable Harvest rates and Carbon Stocks (managed Forests)

- √

- FSC participants should pay attention to the occurrence of live wildlife trees and snags and relative amounts of slash. More specifically, the regional (BC) standard states The detrimental soil disturbance should be limited to 7%–10% of the total forest management unit (Criterion 6.3.14).

- √

- PEFC Criterion 5.3.6 prescribes Harvesting levels of both wood and non-wood forest products shall not exceed a rate that can be sustained in the long term. Optimum use shall be made of the harvested forest products, with due regard to nutrient off-take. Note that the PEFC global criteria are an umbrella for other frameworks to cover this topic (more in detail). Consequently, the loss of nutrients in the forest, after the removal of woody biomass, is not covered by PEFC indicators.

- √

- The SFI program has a three-step approach: criterion 8.1 provides guidance on Management of harvest residues, taking Environmental factors like organic and nutrient value to future forests into consideration. Criterion 1.41 provides Guidance on ecological impacts of bioenergy feedstock removals. Performance measure 2.3 states that Post-harvest conditions conducive to maintaining site productivity (e.g., retained down woody debris). The SFI FM program prescribes a maximum clear cut area of 50 ha, which may cover our concerns of possible carbon loss after large scale harvest (Section 3.4). Note that a 50 ha limit by itself is not a guarantee for carbon maintenance.

- ±

- CSA explicitly includes the Level of soil disturbance (Criterion 3.1.1), together with the Level of downed woody debris (Criterion 3.1.2). However, both parameters are currently under discussion for future inclusion in CSA. It remains unclear whether they are included as a default value during the certification audit (Section 4). Note also that the informative annex (non-mandatory) to the CSA guidelines prescribes Forest managers to develop clear operational guidelines for the removal of biomass. The CSA program does not have a limit for the final felling area, leaving uncertainty about possible carbon losses after large scale felling (Section 3.4).

- ±

- Where present, relevant to the property, and consistent with landowner’s objectives, the ATFS FM plan (Indicator 1.1.2) preparer may consider, describe and evaluate resource elements, amongst them biomass and carbon. Further, no limit for the clear cut area is indicated (similar to CSA before). We consider this item as partially covered, as it remains unsure whether and how intensive biomass harvesting and clear cut are guided and if any restrictions are applied.

E. Preventing Deforestation (Replanting and Natural Generation after Harvest)

- √

- The FSC global standard requires forest regeneration, succession and natural (harvest) cycles for maintaining native species in the long term (Criterion 6.6) plus appropriate regeneration for the landscape values in that region. In BC, natural replanting should use local seedlings or seeds. BC’s Criterion 6.1 states Forest conversion to plantations or non-forest land shall not occur, except in circumstances where conversion (a) entails a very limited portion of the FMU; does not occur on HCV Forest areas; will enable long term conservation benefits etc., across the FMU.

- √

- Under the PEFC International scheme (Criterion 5.1.11), Conversion of forests to other types of land use, including conversion of primary forests to forest plantations, shall not occur unless in justified circumstances where the conversion is in compliance with national laws; entails a small portion of forest type and does not have negative impacts on threatened forest ecosystems etc.

- √

- Within SFI forest management (Objective 2), Natural regeneration and planting should occur within a period of 5 years and 2 years respectively after harvesting has taken place. Monitoring is required to check the progress of regeneration, growth and drain (harvest).

- ±

- CSA has several clauses for preventing deforestation: Element 2.2 Conserve forest ecosystem productivity and productive capacity by maintaining ecosystem conditions that are capable of supporting naturally occurring species. Reforest promptly and use tree species ecologically suited to the site. CSA Element 4.2 Forest land conversion should protect forest lands from deforestation or conversion to non-forests, where ecologically appropriate. Forest managers should address and monitor these elements via two core indicators “Additions and deletions to the forest area” and “Proportion of the calculated long-term sustainable harvest level that is actually harvested”. The first indicator (“additions and deletions …”) is a particular one. After consultation of some public summaries of audit reports [129,130,131,132,133], we conclude that the current defined forest area (DFA) is always indicated, but not the DFA of the previous auditing stage. This raises the concern whether the deforestation monitoring is applicable for the project level (certification stage) or whether it should be monitored at province or at country level (national reporting to the IPCC).

- ➢

- ATFS. There is no specific prescription for this topic, in terms of timing. Only general preferences are stated: natural regeneration stocking assessment should be held and account for both coniferous and non-coniferous species. Based on the anecdotal evidence from a single audit for GGL’s certification program [94], part of the sourced forest area in the southeast US was converted to agricultural purposes after the final cut in 2011. These forests were established by farmers since 1930 and harvested within 20 to 40 years. The larger landowners actively replanted the area, but the smaller ones relied on natural regeneration. Due to their low wood revenues, a small (insignificant) part of these forests is nowadays converted to agriculture [135].

F. Exceptional Removal of Salvage Trees

- √

- FSC regional framework for BC has a Criterion 9.1.1 for natural disturbance regimes and a detailed checklist for the identification of (remnant) intact forest landscapes. In addition, the BC Criterion 6.1.2 states The manager collects inventory information appropriate for landscape level planning and for completion of a forest management plan (FMU level), including a natural disturbance regime. In its explanatory notes [95] to its global framework, FSC states The FM shall reduce potential negative impacts from natural hazards (Criterion 10.9). Pests, plant diseases, etc. can be minimized by clearance of fallen wood, standing dead wood and coarse woody debris, in line with best scientific and local knowledge. Further, the current regional BC standard (Criterion 5.6) requires that in any given year no more than 25% above the projected long-term harvest level shall be recovered unless there is a catastrophic event. Within one year, a 25% limit can be temporarily exceeded but the forest manager must ensure that a 5 year average does not exceed the sustainable long-term level (Annual Allowable Cut or AAC). Overall, FSC has this item sufficiently covered.

- √

- PEFC Criterion 5.2.3 The monitoring and maintaining of health and vitality of forest ecosystems shall take into consideration the effects of naturally occurring fire, pests and other disturbances. In addition, PEFC Criterion 5.4.13 states that Standing and fallen dead wood and hollow trees shall be left in quantities and distribution necessary to safeguard biological biodiversity, taking into account the potential effect on the health and stability of forests and on surrounding ecosystems. We consider these statements as sufficient for the coverage of salvage logging.

- ±

- CSA Criterion 6.3.2 Conserve forest ecosystem condition and productivity by maintaining health, vitality, and rates of biological production, includes a list of discussion items. For example, the public participation process shall include discussion about the proportion of naturally disturbed area that is not salvage harvested. We consider this item as partially covered, as a discussion item is a first step for further inclusion as a core indicator during the audit stage (Section 4).

- ➢

- ATFS Indicator 1.1.1 states Management plan must be active, adaptive, and embody landowner’s current objectives. However, the nature of adaptive management requires that the landowner is not bound to follow the management plan prescriptions when circumstances are influencing the property. Examples of such changes would include major damage from storms, fire, pest or disease outbreaks. For lacking any indicators, we consider this item as insufficient covered.

- ➢

- SFI Program Participants shall manage so as to protect forests from damaging agents, such as environmentally or economically undesirable wildfire, pests, etc., to maintain and improve long-term forest health, productivity and economic viability (Performance Measure 2.4). It remains unclear how the forest is monitored after any exceptional circumstances (i.e., natural disturbances) have occurred. Therefore, we regard this item as insufficiently covered.

D2. Benchmark of Risk Based Assessments (Risk Based Fibers)

- √

- FSC. The main pillar of FSC controlled wood is the avoidance of illegally harvested wood trading.

- √

- PEFC DD is completely set up to comply with the EUTR (see also Section 3.1).

- ✗

- SFI-FS. Generally, fibers within SFI-FS can only be traced back to an aggregated (state) level instead of the desirable level of a regional FMU (see below). We have earmarked this item as insufficient coverage, as state wide coverage can accidentally include a medium or a high risk area.

A. GHG Forest Operations

- ➢

- Similar to the FM benchmark (Appendix D1), the compliance with GHG calculation is insufficiently covered by FSC-CW and PEFC-DD and partially covered by SFI certification.

B. Protection of High Biodiversity Areas, Including Primary Forests

- √

- FSC CW has a main function to prevent trading in wood harvested from forests with high conservation value (HCV) where they are threatened by management activities. Following the FSC harvest restriction to HCV forests, intact forest landscapes are explicitly included as a no-go area.

- ±

- PEFC DD does not allow harvesting from controversial sources. These include, amongst others, forestry operations and harvesting from protected forests with biodiversity conservation values and also the conversion of forest to other uses. PEFC DD includes a clause for the Due Diligence System (see Section 3.1), which prevents the conversion of forest to other vegetation type, including conversion of primary forests to forest plantations (Criterion 5.1.9) However, we regard this clause as partial coverage as wood harvest from primary forest areas is not restricted.

- ±

- Remaining Objective 11 and its performance Measure 11.1 (Program participants of SFI certified sources shall include efforts to promote conservation of biological biodiversity) may be regarded as a first step to guarantee the protection of highly bio-diverseforests in North America. Remarkably, Objective 11 and its measures are not applicable for non-domestic fibers. This exception leaves a risk for fibers from unwanted sources outside North America and the possible mix with domestic fibers into one product. We regard this topic as insufficiently covered.

C. Safeguard of High Carbon Stock Forest Areas (Protected Forest Areas)

D. Sustainable Harvest Rates and Carbon Stocks (Managed Forests)

- ±

- The additional removal of slash and stumps has only one single safeguard left, when fibers switch from the SFI-FM to the SFI-FS program: Criterion 8.1: providing global guidance on the management of harvest residues. It takes environmental factors like organic and nutrient value to future forests into consideration. We regard this global guidance to partially cover this topic, as the monitoring of the level of nutrients (and others), both before and after harvesting, is not required.

- ✗

- This item is not covered at all by the FSC and PEFC complementary frameworks.

E. Preventing Deforestation (Regeneration and Replanting Practices)

- √

- PEFC [72] states the organization shall operate a DDS (Criterion 5.1) to minimize the risk that the procured material originates from controversial sources, like converting forest to other vegetation type (including conversion of primary forests to forest plantations).

- √

- ✗

- In contrast to SFI FM, reforestation has only a voluntary status in SFI-FS. Program participants of SFI-FS shall supply regionally appropriate information or services to forest landowners describing the importance of reforestation and afforestation and providing related implementation guidance.

F. Exceptional Removal of Salvage Trees

- ✗

- This item is not covered by any of the alternative options FSC CW, PEFC DD and SFI FS.

References and Notes

- European Parliament and EU Council. Directive 2009/28/EC on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, L140, 16–62. [Google Scholar]

- For a complete overview of acronyms, see the list of abbreviations at the end of the main paper

- Eurostat. Energy statistics; Supply, tranformation, consumption (1990–2008). Available online: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/energy/data/database (accessed on 2 September 2010).

- Scarlat, N.; Dallemand, J.F.; Banja, M. Possible impact of 2020 bioenergy targets on European land use. A scenario based assessment from NREA proposals. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 18, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. Recommendations for sustainability criteria for forest based biomass in electricity, heating and cooling in Europe. Available online: http://wwf.panda.org (accessed on 1 September 2012).

- European Commission. Directive 2010/995/EC. Obligations of operators who place timber an timber products on the market (EU Timber Regulation). Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, L295, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Timber Regulation. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/eutr2013/index_en.htm (accessed on 25 March 2013).

- Sikkema, R.; Faaij, A.P.C.; Ranta, T.; Heinimo, J.; Gerasimov, Y.Y.; Karjalainen, T.; Nabuurs, G.J. Mobilisation of biomass for energy from boreal forests in Finland and Russia under present SFM certification and new sustainability requirements for solid biofuels. Biomass Bioenerg. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Report to the Council and the European Parliament on sustainability requirements for the use of solid and gaseous biomass sources in electricity, heating and cooling. SEC 2010, 2010 final, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ends Europe. EC officials outline biomass sustainability plans. Available online: http://www.endseurope.com/index.cfm?go=31774 (accessed on 3 March 2014).

- Abbas, D.; Current, D.; Phillips, M.; Rossman, R.; Hoganson, H.; Brooks, K.N. Guidelines for harvesting forest biomass for energy: A synthesis of environmental considerations. Biomass Bioenerg. 2011, 35, 4538–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, U.R.; Iriarte, L.; de Jong, J.; van Thuijl, E.; Lammers, E.; Agostini, A.; Scarlat, N. Sustainability criteria and indicators for solid bioenergy from forests (revised June 2013). Available online: http://www.iinas.org (accessed on 30 August 2013).

- Janowiaw, M.K.; Webster, C.R. Promoting ecological sustainability in woody biomass harvesting. J. For. 2010, 108, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kimsey, M., Jr.; Pag-Dumroese, D.; Coleman, M. Assessing bioenergy harvest risks: Geospatially explicit tools for maintaining soil productivity in Western US forests. Forests 2011, 2, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, W.J.; McKay, H.M.; Weatherall, A.; Connolly, T.; Harrison, A.J. The effects of whole tree harvesting on three sites in upland Britain on the growth of Sitka spruce over 10 years. Forestry 2012, 85, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Dean, T.J. Energy trade-offs between intensive biomass utilization, site productivity loss and ameliorative treatments in loblolly pine plantations. Biomass Bioenerg. 2006, 30, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiffault, E.; Paré, D.; Brais, S.; Titus, B.D. Intensive biomass removals and site productivity in Canada: a review of relevant issues. For. Chron. 2010, 86, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, J.D.; Godbold, D.L. Stump harvesting for bioenergy—A review of the environmental impacts. Forestry 2010, 83, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klockow, P.A.; D’Amato, A.W.; Bradford, J.B. Impacts of post harvest slash and live tree retention on biomass and nutrient stocks in Populus tremuloides Michx.-dominated forests, northern Minnnesota, USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 291, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardell, L. Vegetationsforandring, Plantetablering Samt Barproduktion efter Stub- ock Ristakt Change of Vegetation, Planting and Natural Regeneration after Stump and Slash Removal. Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet: Uppsala, Sweden, 1992; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- UNECE. Forest products: Annual market review 2011–2012. Available online: http://www.unece.org (accessed on 2 July 2013).

- Lamers, P.; Thiffault, E.; Paré, D.; Junginger, H.M. Feedstock specific environmental risk levels related to biomass extraction for energy from boreal and temperate forests. Biomass Bioenerg. 2013, 55, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. EU27 Trade Since 1988 By CN8 (DS-016890). Available online: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/setupDownloads.do (accessed on 17 April 2013).

- Sikkema, R.; Steiner, M.; Junginger, H.M.; Hiegl, W.; Hansen, M.T.; Faaij, A.P.C. The European wood pellet markets: Current status and prospects for 2020. BioFPR 2011, 5, 250–278. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, C.; Cashore, B.V.; Kanowski, P. Global Environmental Forest Policies: An International Comparison; The Earthscan forest library: London, UK, 2010; pp. 1–392. [Google Scholar]

- Berch, S.M.; Bulmer, C.; Curran, M.; Finvers, M.; Titus, B. Provincial government standards, criteria and indicators for sustainable harvest of forest biomass in British Columbia: soil and biodiversity. Int. J. For. Eng. 2012, 23, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chum, H.; Faaij, A.P.C.; Moreiro, J. Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation. Section 2 Bioenergy. Section 2 Bioenergy. Available online: www.ipcc.org (accessed on 17 September 2012).

- Elbehri, A.; Segerstedt, A.; Liu, P. Biofuels and the Sustainability Challenge: A Global Assessment of Sustainaibility Issues, Trends and Policies for Biofuels and Related Feedstocks. FAO Trade & Markets Division: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IEA Bioenergy Task 40. Examing sustainability certification of bioenergy. Available online: www.bioenergytrade.org/publications.html (accessed on 8 November 2013).

- Van der Gaast, W.; Sikkema, R.; Simula, M. Developing synergies between carbon sinks and sustainable forest management. Jt. Implement. Q. 2001, 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Dargusch, P.; Maraseni, T.N.; Schmidt, P. A review of research on forest related environmental markets, including certification schemes, bioenergy, carbon markets and other ecosystem services. CAB Rev.: Perspect. Agric. Vet. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2010, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Energy & Climate Change. Biomass electricity and CHP plants—Ensuring sustainability and affordability. Available online: http://www.decc.gov.uk/ (accessed on 25 November 2012).

- CPET. UK public procurement policy on timber. Available online: http://www.cpet.org.uk/ (accessed on 24 May 2013).

- DEFRA. Definition of legal and sustainable for timber procurement. Available online: http://www.cpet.org.uk/uk-government-timber-procurement-policy/definitions/defining-legality-and-sustainability (accessed on 4 June 2013).

- SFC. Opinion on sustainability criteria for solid and gaseous biomass in electricity, heating and cooling. Standing Forestry Committee (25 January 2013). Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/fore/opinion-docs/sfc-opinion-biomass-sustainability-criteria_en.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2013).

- Draft criteria for solid biomass were leaked in August 2013, but not used in our article due to their unofficial status

- FSC International Center. The Revised Principles & Criteria. Requirements for Forest Management Certification. FSC-STD-01–001 V5–0. Available online: https://ic.fsc.org/the-revised-pc.191.htm (accessed on 12 December 2011).

- Brazil and France recently proposed to introduce one uniform ISO management standard for the COC of forest-based products. This standard intends to integrate different FSC and PEFC procedures into one supply chain document

- Feilberg, P.; Hain, H.; Sloth, C.; van Boven-Flier, D. Comparative Analysis of the PEFC System with FSC Controlled Wood Requirements; NEPCON: Aarhus, Denmark, 2012; pp. 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- Endres, J.M. Barking up the wrong tree? Forest sustainability in the wake of emerging bioenergy policies. Available online: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2197386 (accessed on 19 April 2013).

- SFI Program. SFI Fiber Sourcing and FSC Controlled Wood: How These Standards Address Uncertified Content in the Supply Chain. Available online: www.sfiprogram.org/files/pdf/bnuncertifiedwood20091120pdf/ (accessed on 30 May 2013).

- SFI Program. SFI 2010–2014 Standard for Forest Management. Available online: www.sfiprogram.org/standards-and-certifications/sfi-standard/ (accessed on 12 December 2011).

- Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. Legislation and Regulations British Columbia. Available online: www.for.gov.bc.ca/tasb/legsregs/ (accessed on 18 May 2013).

- Indufor. Table 1 National/state level laws to identify normative regulations of the forest management elements. In Legislation British Columbia, Canada; CSA, Ed.; Indufor: Helsinki, Finland, 2008; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.F. Georgia’s Best Management Practices. Available online: www.georgiaplanning.com (accessed on 25 October 2012).

- Kittler, B.; Price, W.; McDow, W.; Larson, B. Pathways to sustainability—An evaluation of forestry programs to meet European biomass supply chain requirements. EDF and Pinchot Institute for Conservation. Available online: www.edf.org/bioenergy (accessed on 1 September 2012).

- Neary, D.G. Best management practices for forest bioenergy programs. WIREs Energy Environ. 2013, 2, 614–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rametsteiner, E.; Simula, M. Forest certification—An instrument to promote SFM? J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 67, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbrandsen, L.H. Overlapping public and private governance: Can forest certification fill the gaps in the global forest regime? Glob. Environ. Politics 2004, 4, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Henriques, I. Stakeholder influences on sustainability practices in the Canadian forest products industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DG Energy. State of Play on the Sustainability of Solid and Gaseous Biomass Used for Electricity, Heating and Cooling in the EU (SWD 259 Final). Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/energy/renewables/bioenergy/sustainability_criteria_fr.htm (accessed on 28 July 2014).

- Department of Energy & Climate Change. New Biomass Sustainability Criteria to Provide Certainty for Investors to 2027. Available online: www.gov.uk/government/news/new-biomass-sustainability-criteria-to-provide-certainty-for-investors-to-2027 (accessed on 23 August 2013).

- Murray, G. Canadian wood pellet export situation. In Proceedings of the Pellet Fuels Institute Annual Conference, Asheville, NC, USA, 28–30 July 2013.

- Espinoza, O.; Buehlmann, U.; Smith, B. Forest certification and green building standards: Overview and use in the US hardwood industry. J. Clean. Product. 2012, 33, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. State of the World’s Forests; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011; pp. 1–165. [Google Scholar]

- FSC International Center. Facts and figures February 2014. Available online: https://ic.fsc.org/facts-figures.19.htm (accessed on 7 March 2014).

- PEFC. PEFC Global Certification (per March 2013). Available online: www.slideshare.net/fullscreen/PEFC/pefc-global-certificates (accessed on 7 March 2014).

- Cocchi, M. Global Wood Pellet Industry Market and Trade Study. Available online: www.bioenergytrade.org (accessed on 23 June 2013).

- Van Dam, J.; Junginger, H.M.; Faaij, A.P.C. From the global efforts on certification of bioenergy towards an intergrated approach on sustainable land use planning. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 2445–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, J.; Junginger, H.M.; Faaij, A.P.C.; Jürgens, I.; Best, G. Overview of recent developments in sustainable biomass certification. Biomass Bioenerg. 2008, 32, 749–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Corbey. Drie times sustainable; advise for sustainable cofiring of solid biomass. (In Dutch: driemaal duurzaam: advies duurzame bij- en meestook vaste biomassa). Available online: www.corbey.nl/adviezen/vaste-biomassa/drie-maal-duurzaam/ (accessed on 24 April 2013).

- Agentschap, N.L. Green Deal Sustainbility of Solid Biomass; Green deal duurzaamheid vaste biomass: Utrecht, the Netherlands, 2012; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- More EU member states have introduced a separate tool (“add on”) to compile the GHG life cycle emissions for forest operations and downstream wood supplies, as these types of calculations are outside the scope of existing SFM certificates for wood and paper products

- Department of Energy & Climate Change. Timber Standard for Heat and Electricity. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/ (accessed on 10 February 2014).

- GDF Suez. Biomass Verification Procedure (BVP). Laborelec, Linkebeek, Belgium. Available online: http://www.laborelec.be/ENG/biomass-verification-procedure/ (accessed on 14 September 2012).

- Green Gold Label Foundation. GGL Program. Available online: http://www.greengoldcertified.org/site/pagina.php?id=9 (accessed on 12 February 2013).

- Drax. Sustainability Policy for Biomass. Available online: www.draxpower.com/biomass/sustainability_policy/ (accessed on 28 October 2012).

- Ryckmans, Y. Presentation Sustainable Biomass Partnership (SBP). Laborelec, Linkebeek, Belgium. Available online: www.laborelec.be/ENG/services/biomass-analysis/initiative-wood-pellet-buyers-iwpb/ (accessed on 6 November 2013).

- Van Dam, J.; Ugarte, S.; Sikkema, R.; Schipper, E. The Use of Post Consumer Wood Waste in the US for Pellet Production (Final Report); Agentschap NL: Utrecht, the Netherlands, 2013; pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam, J. Lessons Learned from the Netherlands Program Sustainable Biomass (NPSB) 2009–2013; Netherlands Entreprise Agency: Utrecht, the Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1–175. [Google Scholar]

- FSC International Center. Standard for Chain of Custody Certification. FSC-STD-40-004 (V2-1) EN. Available online: http://us.fsc.org (accessed on 3 November 2013).

- PEFC International. Chain of Custody of Forest Based Products—Requirements. PEFC ST 2002:2013. Available online: www.pefc.org (accessed on 24 May 2013).

- European Commission. Directive 2008/98/EC on waste and repealing certain Directives (Waste framework Directive). Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, L312, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Homeland Security. Lacey Act. Available online: www.cbp.gov/xp/cgov/trade/trade_programs/entry_summary/laws/food_energy/amended_lacey_act/lacey_act.xml (accessed on 22 September 2013).

- Florian, D.; Masiero, M.; Mavsar, R.; Pettenella, D. How to support the implementation of Due Diligence systems through the EU Rural Development Program: problems and potentials. L’Italia forestale e montana 2012, 67, 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- FSC International Center. FSC and the Australian Illegal Logging Prohibition Act 2012. Available online: http://ic.fsc.org/download.fsc-and-the-australian-illegal-logging-prohibition-act-2012.701.htm (accessed on 22 September 2013).

- Butler, G.; Grant, A. Shedding light on rules and regulations. Available online: www.ttjonline.com (accessed on 22 September 2013).

- Scarlat, N.; Dallemand, J.F. Recent developments of biofuels/bioenergy sustainability certification: A global overview. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 1630–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEPF & Eustafor. Joint Position: Forest Owners Question Binding EU Sustainability Criteria for Solid Biomass. Available online: www.cepf-eu.org (accessed on 19 August 2013).

- Pilzecker, A. EU Biomass Policies. In Proceedings of the European Pellet Conference, Wels, Austria, 28 February 2013; Powerpoint presentation. pp. 1–20.

- CEPI. Biomass Sustainability Criteria should be binding and harmonised. Available online: www.cepi.org (accessed on 2 July 2013).

- CEI-Bois. Memorandum to the European Institutions. Available online: www.cei-bois.org/en/publications (accessed on 3 July 2013).

- Gerasimov, Y.Y. Energy Sector in Belarus: Focus on Wood and Peat Fuel; Metla: Joensuu, Finland, 2010; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema, R.; Junginger, H.M.; McFarlane, P.; Faaij, A.P.C. The GHG contribution of the cascaded use of harvested wood products in comparison with the use of wood for energy—A case study on available forest resources in Canada. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 31, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurelectric. Aebiom and Eurelectric call for EU wide binding sustainability criteria for biomass now (press release 13 March 2013). Available online: www.eurelectric.org (accessed on 2 July 2013).

- Levidow, L. EU criteria for sustainable biofuels: accounting for carbon, depoliticising plunder. Geoforum 2013, 44, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Similar administrative restrictions are also valid for unprocessed waste chips from painted wood and glued panels (B-grade)

- Stovall, J. Regeneration Methods: Clearcut. Available online: http://forestry.sfasu.edu/faculty/jstovall/silviculture/index.php/silviculture-textbook/166-clearcut (accessed on 18 May 2013).

- Agostini, A.; Guintoli, J.; Boulamanti, A. Carbon Accouting of Forest Bioenergy. Available online: iet.jrc.ec.europa.eu/bf-ca/sites/bf-ca/files/files/documents/eur25354en_online-final.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2013).

- Holtsmark, B. Quantifying the global warming potential of CO2 emissions from wood fuels. GCB Bioenerg. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndes, G.; Ahlgren, S.; Böresson, Cowie, A.L. Bioenergy and land use change—State of the art. WIREs Energy Environ. 2013, 2, 282–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malins, C. A model-based quantitative assessment of the carbon benefits of introducting iLUC factors in the European RED. GCB Bioenergy 2013, 5, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicke, B.; Verweij, P.; van Meij, H.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Faaij, A.P.C. Indirect land use change: Review of existing models and strategies for mitigation. Biofuels 2012, 3, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Control Union Certifications. Green Gold Label (CUSI) Database for Pellet Production Units, International Traders and Power Companies; Control Union: Zwolle, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- FSC International Center. FSC Principles & Criteria for Forest Stewardship. Explanatory Notes and Rationales. Available online: http://igi.fsc.org/download.fsc-pc-v5-with-explanatory-notes.58.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2012).

- FSC Canada. Regional Forest Management Standards. British Columbia. Available online: https://ca.fsc.org/regional-fm-standards.201.htm (accessed on 12 December 2011).

- PEFC International. Sustainable Forest Management. PEFC ST 1003:2010. Available online: www.pefc.org (accessed on 25 October 2012).

- Compliance is verified through an independent assessment and limited to 5 years. National forest certification systems are required to revise their standards to also incorporate any modifications to PEFC International’s standard before they are eligible to apply for re-endorsement (Personal Communication with Johan de Vlieger, PEFC International)

- SFI Program. Interpretations for SFI 2010–2014 program requirements. Available online: http://www.sfiprogram.org/files/pdf/interpretations2010–2014requirements.pdf/ (accessed on 7 November 2012).

- Canadian Standards Association. Forest Management standards. CAN/CSA Z809. Available online: www.csasfmforests.ca/forestmanagement.htm (accessed on 12 December 2011).

- American Tree Farm System Standards of Certification. 2010—2015. Available online: www.treefarmsystem.org/documents (accessed on 27 March 2012).

- Gold Standard. Afforestation—Reforestation requirements. Draft for public comment 28 May until 28 June 2013. Available online: www.cdmgoldstandard.org (accessed on 6 April 2013).

- FSC International Center. FSC Controlled Wood Standard for Forest Management Enterprises. FSC-STD-30–010 (V2–0) EN. Available online: http://us.fsc.org (accessed on 23 June 2013).

- FSC International Center. Standard for Company Evaluation of FSC Controlled Wood. FSC-STD-40–005 (V 2–1) EN. Available online: http://us.fsc.org (accessed on 23 June 2013).

- Due to the latest modifications by PEFC [97], national forest systems (like in North America: SFI-FM, CSA and ATFS) have to revise and incorporate the modifications before the periodical re-endorsement process (e.g. every 5 years). Thus, there can be some delay in the PEFC coverage

- Hickey, G.M.; Innes, J.L. Indicators for demonstrating SFM in British Columbia, Canada: An international review. Ecol. Indic. 2008, 8, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiffault, E.; Endres, J.M.; Fritsche, U.; Iriarte, L. Sustainability of Wood Bioenergy Supply Chains: Operational and International Policy Perspectives; IEA Bioenergy Task 40: Quebec, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- As such, ATFS will deliver “non-approved” fibers to pellet plants in North America, where they must comply with UK’s other Evidence B (see Appendix B)

- PEFC International. PEFC logo usage rules—Requirements. PEFC ST 2001:2008. Available online: www.pefc.org (accessed on 17 November 2013).

- Evans, A.M.; Perschel, R.T.; Kittler, B.A. Revised Assessment of Biomass Harvesting and Retention Guidelines. Available online: www.forestguild.org/publications/research/2009/biomass_guidelines.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2013).

- Lazdins, A.; Lazdina, D.; Klavs, G. Preliminary results of estimation of forest biomass for energy potentials in final felling using a system model. Renew. Energy Energy Effic. 2012, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, M. Seeing the Forest for the Trees—Latvia’s Green Gold. Available online: www.baltictimes.com/news/articles/28529/ (accessed on 2 July 2013).

- Ellison, D.; Peterson, H.; Lundblad, M.; Wikberg, P.E. The incentive gap: LULUCF and the Kyoto mechanism before and after Durban. GCB Bioenergy 2013, 5, 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Gaast, W. CDM and JI projects in the pipeline (database UNECP RISO center). Available online: www.cdmpipeline.org (accessed on 13 October 2013).

- Merger, E.; Dutschke, M.; Verchot, L. Options for REDD+ voluntary certification to ensure net GHG benefits, poverty alleviation, sustainable management of forests and biodiversity conservation. Forests 2011, 2011, 550–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Volume 4 Agriculture, Forestry and other Land Use. Available online: www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/vol4.html (accessed on 15 January 2012).

- Croatia became the 28th EU member country on 1 July 2013; table A1 data refer to the EU-27.

- Buongiorno, J.; Zhu, S.; Raunikar, R.; Prestemon, J.P. Outlook to 2060 for World Forests and Forest Industries: A Technical Document SUpporting the Forest Service 2010 RPA Assessment. US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, US, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Production and Consumption of Wood in the EU27. Available online: europa.eu/rapid/press-release_STAT-12–168_en.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2012).

- Mantau, U. Wood Flows in Europe. CEPI and CEI Bois. Available online: www.cepi.org (accessed on 29 September 2013).

- CEPI. Key Statistics European Pulp and Paper Industry 2012. Available online: www.cepi.org (accessed on 29 September 2013).

- Hendrickx, B. Use of raw material by European forest sector. In Proceedings of the EPF Annual Meeting, Brussels, Belgium, 10 March 2010; pp. 1–2.

- CPET. UK Government Timber Procurement Policy. Internet document; 3rd ed. (July 2010). Available online: http://www.cpet.org.uk (accessed on 3 July 2014).

- Informative Annexes are non-mandatory parts of the SFM framework [100]

- Nill, M. Integration of Carbon Emission Criteria into PEFC’s Standards and Procedures. In Proceedings of the PEFC Stakeholder Dialogue, Vienna, Austria, 14 November 2012; PEFC; pp. 1–8.

- IAE Bioenergy Task 40. The Science Policy Interface of the Environmental Sustainability of Forest Bioenergy. In Proceedings of the Workshop Sustainability of Forest Bioenergy in Canada, Quebec, QC, Canada, 3–5 October 2012.

- Naturally Wood. Examing the linkage between forest regulation and forest certification around the world. Available online: www.naturallywood.com (accessed on 18 May 2013).

- SFI. Audit and Reports. Available online: www.sfiprogram.org/sfi-standard/audit-reports (accessed on 23 October 2013).

- KPMG. ISO 14001 Periodic Assessment & CSAS Z809 Scope. Available online: www.dmi.ca (accessed on 23 October 2013).

- KPMG. Forest Certification Report CSA Z809–08 Audit. Available online: www.for.gov.bc.ca (accessed on 23 October 2013).

- KPMG. CSA Z809 Surveillance report (public summary). Available online: www.canfor.com (accessed on 23 October 2013).

- SAI Global. SFM System—CAN/CSA—Z809-2008 (June 2013). Available online: www.westernforest.com (accessed on 23 October 2013).

- SAI Global. Tolko Industries. Forest Certification Update. Available online: www.tolko.com (accessed on 23 October 2013).

- KPMG. Examining carbon accounting and sustainable forestry certification. Available online: www.climateactionreserve.org (accessed on 8 November 2013).

- Meyers, S. US Forest Plantation Practices (email 29 October 2013); FRAM Renewable Fuels: Savannah, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]