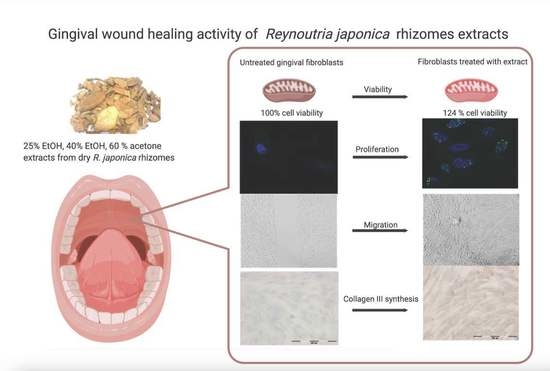

In Vitro Gingival Wound Healing Activity of Extracts from Reynoutria japonica Houtt Rhizomes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Extract Preparation

2.2. HPLC/DAD/ESI-HR-QTOF-MS Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

2.2.1. HPLC Apparatus

2.2.2. HPLC-DAD-MS Conditions

2.3. Total Polyphenols and Tannins Content

2.4. Cell Culture

2.5. Cell Viability Assay

2.6. Confocal Laser Microscopy Study

2.7. In Vitro Wound Healing Assay

2.8. Immunocytochemical Staining

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cell Viability—MTT Assay

3.2. Confocal Laser Microscopy Study

3.3. Wound Healing Assay

3.4. Immunocytochemical Staining

3.5. HPLC/DAD/ESI-HR-TOF-MS Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

3.6. Total Polyphenols and Tannins Content

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng, W.; Qin, R.; Li, X.; Zhou, H. Botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and potential application of Polygonum cuspidatum Sieb. et Zucc.: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempen, C.-H.; Fischer, T. A Materia Medica for Chinese Medicine: Plants, Minerals, and Animal Products; Churchill Livingstone-Elsevier: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780443100949. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.-H.; Kim, S.-K.; Chang, K.-W.; Han, S.-K.; Yi, H.-K.; Jeon, J.-G. In vitro inhibitory effects of Polygonum cuspidatum on bacterial viability and virulence factors of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus. Arch. Oral Biol. 2006, 51, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-B.; Luo, X.-Q.; Gu, S.-Y.; Xu, J.-H. The effects of Polygonum cuspidatum extract on wound healing in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 934–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Hadzik, J.; Fleischer, M.; Choromańska, A.; Sterczała, B.; Kubasiewicz-Ross, P.; Saczko, J.; Gałczyńska-Rusin, M.; Gedrange, T.; Matkowski, A. Chemical composition of east Asian invasive knotweeds, their cytotoxicity and antimicrobial efficacy against cariogenic pathogens: An in-vitro study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 3279–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riss, T.L.; Moravec, R.A.; Niles, A.L.; Duellman, S.; Benink, H.A.; Worzella, T.J.; Minor, L. Cell viability assays. In Assay Guidance Manual; Eli Lilly & Company: Indianapolis, Indiana; The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.C.; Cáceres, M.; Martínez, C.; Oyarzún, A.; Martínez, J. Gingival wound healing: An essential response disturbed by aging? J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterczala, B.; Kulbacka, J.; Saczko, J.; Dominiak, M. The effect of dental gel formulation on human primary fibroblasts—An in vitro study. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2020, 58, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buranasin, P.; Mizutani, K.; Iwasaki, K.; Na Mahasarakham, C.P.; Kido, D.; Takeda, K.; Izumi, Y. High glucose-induced oxidative stress impairs proliferation and migration of human gingival fibroblasts. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buranasukhon, W.; Athikomkulchai, S.; Tadtong, S.; Chittasupho, C. Wound healing activity of Pluchea indica leaf extract in oral mucosal cell line and oral spray formulation containing nanoparticles of the extract. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Field, E.A.; Allan, R.B. Oral ulceration—Aetiopathogenesis, clinical diagnosis and management in the gastrointestinal clinic. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 18, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, M.; Oyarzun, A.; Smith, P. Defective Wound-healing in Aging Gingival Tissue. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teixeira, D.D.S.; De Figueiredo, M.A.Z.; Cherubini, K.; Oliveira, S.; Salum, F.G. The topical effect of chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine in the repair of oral wounds. A review. Stomatol. Balt. Dent. Maxillofac. J. 2019, 21, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes, Z.L.; Bescos, R.; Belfield, L.A.; Ali, K.; Roberts, A. Current uses of chlorhexidine for management of oral disease: A narrative review. J. Dent. 2020, 103, 103497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laugisch, O.; Ramseier, C.A.; Salvi, G.E.; Hägi, T.T.; Bürgin, W.; Eick, S.; Sculean, A. Effects of two different post-surgical protocols including either 0.05 % chlorhexidine herbal extract or 0.1 % chlorhexidine on post-surgical plaque control, early wound healing and patient acceptance following standard periodontal surgery and implant placement. Clin. Oral Investig. 2016, 20, 2175–2183. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Granica, S.; Domaradzki, K.; Pecio, Ł.; Matkowski, A. Isolation and Determination of Phenolic Glycosides and Anthraquinones from Rhizomes of Various Reynoutria Species. Planta Med. 2018, 84, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cieslak, A.; Zmora, P.; Matkowski, A.; Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Pers-Kamczyc, E.; El-Sherbiny, M.; Bryszak, M.; Szumacher-Strabel, M. Tannins from Sanguisorba officinalis affect in vitro rumen methane production and fermentation. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2016, 26, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Granica, S.; Abel, R.; Czapor-Irzabek, H.; Matkowski, A. Analysis of Antioxidant Polyphenols in Loquat Leaves using HPLC-based Activity Profiling. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berghorn, K.A.; Bonnett, J.H.; E Hoffman, G. cFos immunoreactivity is enhanced with biotin amplification. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1994, 42, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clément, C.; Orsi, G.; Gatto, A.; Boyarchuk, E.; Forest, A.; Hajj, B.; Miné-Hattab, J.; Garnier, M.; Gurard-Levin, Z.A.; Quivy, J.-P.; et al. High-resolution visualization of H3 variants during replication reveals their controlled recycling. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komar, D.; Juszczynski, P. Rebelled epigenome: Histone H3S10 phosphorylation and H3S10 kinases in cancer biology and therapy. Clin. Epigenet. 2020, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Ślusarczyk, S.; Granica, S.; Hadzik, J.; Matkowski, A. Phytochemical Diversity in Rhizomes of Three Reynoutria Species and their Antioxidant Activity Correlations Elucidated by LC-ESI-MS/MS Analysis. Molecules 2019, 24, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Choromańska, A.; Abel, R.; Preissner, R.; Saczko, J.; Matkowski, A.; Hadzik, J. Cytotoxic effect of vanicosides a and b from Reynoutria sachalinensis against melanotic and amelanotic melanoma cell lines and in silico evaluation for inhibition of BRAFV600E and MEK1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakar, A.R.; Haque, M. Preparation of medicinal plants: Basic extraction and fractionation procedures for experimental purposes. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2020, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, M.; Pellegrini, N.; Fogliano, V. The effect of cooking on the phytochemical content of vegetables. J. Sci. Food Agric 2014, 94, 1057–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuorro, A.; Iannone, A.; Lavecchia, R. Water–Organic Solvent Extraction of Phenolic Antioxidants from Brewers’ Spent Grain. Processes 2019, 7, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, A.P.; Singh, R.; Verma, S.S.; Rai, V.; Kaschula, C.H.; Maiti, P.; Gupta, S.C. Health benefits of resveratrol: Evidence from clinical studies. Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 39, 1851–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, Y.T.; Hsieh, M.T.; Lin, C.Y.; Kuo, P.J.; Yang, Y.C.S.H.; Shih, Y.J.; Lai, H.Y.; Cheng, G.Y.; Tang, H.Y.; Lee, C.C.; et al. 2,3,5,4′-tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-glucoside isolated from Polygoni Multiflori ameliorates the development of periodontitis. Mediators Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 6953459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, R.; Lechtenberg, M.; Sendker, J.; Petereit, F.; Deters, A.; Hensel, A. Wound-healing plants from TCM: In vitro investigations on selected TCM plants and their influence on human dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes. Fitoterapia 2013, 84, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruya, M.; Niwano, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Kanno, T.; Nakashima, T.; Egusa, H.; Sasaki, K. Acceleration of Proliferative Response of Mouse Fibroblasts by Short-Time Pretreatment with Polyphenols. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 174, 2223–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downey, M.; Hanlin, R. Comparison of Ethanol and Acetone Mixtures for Extraction of Condensed Tannin from Grape Skin. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2016, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kisseih, E.; Lechtenberg, M.; Petereit, F.; Sendker, J.; Zacharski, D.; Brandt, S.; Agyare, C.; Hensel, A. Phytochemical characterization and in vitro wound healing activity of leaf extracts from Combretum mucronatum Schum. & Thonn.: Oligomeric procyanidins as strong inductors of cellular differentiation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 174, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, Y.-T.; Cheng, G.-Y.; Shih, Y.-J.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, S.-J.; Lai, H.-Y.; Whang-Peng, J.; Chiu, H.-C.; Lee, S.-Y.; Fu, E.; et al. Therapeutic applications of resveratrol and its derivatives on periodontitis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1403, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Matkowski, A.; Hadzik, J.; Dobrowolska-Czopor, B.; Olchowy, C.; Dominiak, M.; Kubasiewicz-Ross, P. Proanthocyanidins and Flavan-3-Ols in the Prevention and Treatment of Periodontitis—Antibacterial Effects. Nutrients 2021, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Matkowski, A.; Kubasiewicz-Ross, P.; Hadzik, J. Proanthocyanidins and Flavan-3-ols in the prevention and treatment of Periodontitis—Immunomodulatory effects, animal and clinical studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sculean, A.; Gruber, R.; Bosshardt, D.D. Soft tissue wound healing around teeth and dental implants. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41 (Suppl. S15), S6–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, P.C.; Martínez, C.; Martínez, J.; McCulloch, C.A. Role of Fibroblast Populations in Periodontal Wound Healing and Tissue Remodeling. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giannelli, M.; Chellini, F.; Margheri, M.; Tonelli, P.; Tani, A. Effect of chlorhexidine digluconate on different cell types: A molecular and ultrastructural investigation. Toxicol. In Vitro 2008, 22, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, G.; Cardoso, C.R.; Larson, R.E.; Silva, J.S.; Rossi, M.A. Chlorhexidine-induced apoptosis or necrosis in L929 fibroblasts: A role for endoplasmic reticulum stress. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009, 234, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Incubation Time (h) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 48 | 72 | |

| untreated cells | 3% | 30% | 50% |

| 25% EtOH | 20% | 60% | 85% |

| 40% EtOH | 7% | 60% | 80% |

| 60% acetone | 7% | 50% | 50% |

| commercial rinse | 0% | 15% | 15% |

| Sample | The Intensity of Staining | Stained Cells (%) |

|---|---|---|

| untreated cells | − | 96 ± 2 |

| positive control | ++ | 95 ± 1.5 * |

| 25% EtOH extract | +/++ | 97 ± 3 * |

| 40% EtOH extract | ++/+++ | 98 ± 2 * |

| 60% acetone extract | ++ | 95 ± 1 * |

| commercial rinse | − | 98 ± 1.5 * |

| Nr. | Compound | Rt. (min) | UV max (nm) | m/z (M − H)− | Error (ppm) | Ion Formula | MS2 Main-Ion (Relative Intensity %) | MS2 Fragments (Relative Intensity %) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unknown carbohydrate, e.g., sucrose | 1.0 | ND | 341.1093 | −1.0 | C12H21O11 | 113.0235(100) | 119(77),101(66), 173(25), 179(23) | HMDB0000258 |

| 2 | Unknown carbohydrate | 1.05 | ND | 719.2032 | 1.2 | C30H39O20 | 377.0864(100) | 379(27), 341(13), 179(10) | − |

| 3 | Unknown | 1.1 | ND | 439.0815 | 1.9 | C26H15O7 | 96.9622(100) | 241(6) | − |

| 4 | Organic acid, e.g., malic acid | 1.15 | ND | 133.0145 | −2.2 | C4H5O5 | 115.0031(100) | HMDB0000156 | |

| 5 | Organic acid, e.g., citric acid | 1.3 | ND | 191.0200 | −1.4 | C6H7O7 | 111.0085(100) | HMDB0000094 | |

| 6 | Procyanidin dimer, Type B | 1.6–1.8 | 225,280 | 577.1350 | 0.2 | C30H25O12 | 289.0724(100) | 407(60), 125(37), 425(16) | [23] |

| 7 | Procyanidin trimer, Type B | 1.8–1.9 | 225,280 | 865.198 | 0.6 | C45H37O18 | 575(100) | 287(93), 577(80), 695(57) | [23] |

| 8 | Procyanidin dimer, Type B | 1.9–2.0 | 225,280 | 577.1345 | 1.8 | C30H25O12 | 289.0719(100) | 407(69), 125(41), 425(22) | [23] |

| 9 | Procyanidin trimer, Type B | 2.0–2.1 | 225,280 | 865.1988 | −0.3 | C45H37O18 | 577.1341(100) | 287(92), 575(90), 865(75), 425(58), 289(45), 695(44), 713(42) | [23] |

| 10 | Catechin | 2.1 | 225,280 | 289.0721 | −1.1 | C15H13O6 | 123.0451(100) | 109(90), 125(73), 245(36) | [23] |

| 11 | Procyanidin dimer, Type B | 2.2 | 225,280 | 577.1358 | −1.1 | C30H25O12 | 289.0723(100) | 407(62), 125(33), 425(20) | [23] |

| 12 | Procyanidin dimer, Type B | 2.4 | 225,280 | 577.1350 | 0.2 | C30H25O12 | 289.0724(100) | 407(60), 125(39), 425(15) | [23] |

| 13 | Epicatechin | 2.8 | 225,280 | 289.0724 | −0.8 | C15H13O6 | 109.0293(100) | 123(95), 221(81), 125(77) | [23] |

| 14 | Procyanidin trimer, Type B | 3.3 | 225,280 | 865.2000 | −1.7 | C45H37O18 | 577.1340(100) | 287(82), 575(75), 865(66), 425(54), 713(44), 413(42), 695(40) | [23] |

| 15 | Piceatannol glucoside | 3.4 | 220,290,318 | 405.1197 | −1.4 | C20H21O9 | 243.0668(100) | 244(14), 245(2), 201(1) | [16] |

| 16 | Procyanidin dimer monogallate | 3.6 | 225,280 | 729.1448 | 1.8 | C37H29O16 | 407.0787(100) | 289(46), 577(29), 451(21) | [23] |

| 17 | Resveratrolside | 3.8 | 220,304,315 | 389.1249 | −1.8 | C20H21O8 | 227.0716(100) | 228(16), 225(9), 185(2) | [16] |

| 18 | Procyanidin dimer monogallate | 4.1 | 225,280 | 729.1463 | −0.2 | C37H29O16 | 407.0776(100) | 289(62), 577(45), 441(29), 451(27) | [23] |

| 19 | Procyanidin tetramer, Type B | 4.6 | 225,280 | 1153.2605 | 1.3 | C60H49O24 | [23] | ||

| 20 | Unknown | 5.5 | 220,275 | 269.0124 | 2.7 | C7H9O11 | 189.0559 (100) | − | |

| 21 | Piceid | 6.0 | 220,304,315 | 389.1248 | −1.6 | C20H21O8 | 227.0715(100) | 228(14), 185(2), 225(0.5) | [16] |

| 22 | Epicatechin-3-O-gallate | 6.3 | 220,279 | 441.0829 | −0.3 | C22H17O10 | 169.0142(100) | 289(55), 125(22), 245(13) | [16] |

| 23 | Procyanidin trimer monogallate | 6.7–6.8 | 225,280 | 1017.2140 | −4.4 | C52H41O22 | 729.1431(100) | 577(30), 865(29), 287(27), 441(19) | [23] |

| 24 | Procyanidin tetramer monogallate | 7.3 | 225,280 | 652.1308 [M − 2H]2−, 1305.2683 | −6.4 | C67H53O28 | 125.0243(100) | 169(96), 289(54), 407(26), 451(11), 577(7), 729(5) | [23] |

| 25 | Resveratrol hexoside | 7.8 | 220,304,315 | 389.1242 | −0.1 | C20H21O8 | 227.0713(100) | 228(15), 185(1), 143(0.5) | [16] |

| 26 | Resveratrol derivative | 8.4 | 220,282,325 | 431.1349 | −0.3 | C22H23O9 | 227.0714(1000) | 228(14), 185(1) | [16] |

| 27 | Resveratrol hexoside | 8.7 | 220,304,315 | 389.1247 | −1.3 | C20H21O8 | 227.0716(100) | 228(15), 185(2), 143(0.5) | [16] |

| 28 | Aloesone hexoside | 9.0 | 220,280,420 | 393.1199 | −2.0 | C19H21O9 | 231.0664(100) | 232(14),187(0.5) | HMDB35734 |

| 29 | Emodin-glucoside | 9.7 | 221,247,269,281,423 | 431.0989 | −1.2 | C21H19O10 | 431.0984(100) | 269.0456(77) | [16] |

| 30 | Lapathoside D | 10.0 | 220, 290, 315 | 633.1818 | 1.2 | C30H33O15 | 145.0295(100) | 487(43), 633(30) | [23] |

| 31 | Resveratrol | 10.6 | 220,306,319 | 227.0716 | −1.2 | C14H11O3 | 143.0499(100) | 185(82), 227(38) | [16] |

| 32 | Torachrysone- hexoside | 12.3 | 226,266,325sh | 407.1352 | −1.1 | C20H23O9 | 245.0823(100) | 246(14), 230(11) | [16] |

| 33 | Emodin-glucoside | 12.8 | 221,269,281, 423 | 431.0987 | −0.9 | C21H19O10 | 269.0459(100) | 311(5) | [16] |

| 34 | Emodin-8-O-(6′-O-malonyl)-glucoside | 14.2 | 220,281,423 | 517.0991 | −0.7 | C24H21O13 | 473.1087(100) | 269(65), 311(4) | [16] |

| 35 | Unknown Torachrysone derivative | 14.5 | 220,266,325sh | 449.1457 | −0.9 | C22H25O10 | 245.0818(100) | 246(14) | − |

| 36 | Torachrysone | 14.8 | 220,312 | 245.0824 | −1.8 | C14H13O4 | 230.0589(100) | 215(52) | [16] |

| 37 | Physcionin/Rheochrysin | 15 | 221,272,423 | 445.1136 | 0.9 | C22H21O10 | 283.0610(100) | 284(17), 307(5) | HMDB0040511/HMDB35931 |

| 38 | Emodin bianthrone-hexose-(malonic acid)-hexose | 15.5 | 220,280,325 | 919.2318 | −1.7 | C45H43O21 | 458.1215(100) | 416(49), 671(18), 713(14), 875(13) | [23] |

| 39 | Hydropiperoside | 15.7 | 222,298,313 | 779.2188 | 0.7 | C39H39O17 | 779.2176(100) | 145(80),633(61), 453(6), 615(5) | [16] |

| 40 | Emodin bianthrone-hexose-(malonic acid)-hexose | 16.1 | 220,280,325 | 919.2300 | 0.2 | C45H43O21 | 458.1207(100) | 416(50), 502(28), 713(18), 671(18), 875(16) | [23] |

| 41 | Derivative of Emodin bianthrone-hexose-malonic acid | 16.4 | 220,280,325 | 1005.2321 | −1.5 | C48H45O24 | 458.1222(100) | 502(27), 713(21), 917(11), 961(5) | [23] |

| 42 | Unknown physcion derivative | 17 | 220, 275, 423 | 1063.2355 | 0.6 | C50H47O26 | 283.0607(100) | 325(13), 487(7) | − |

| 43 | Emodin bianthrone-hexose-(malonic acid)-hexose | 17.1 | 220,280,325 | 919.2309 | −0.6 | C45H43O21 | 458.1214(100) | 416(43), 502(25), 713(15), 671(15), 875(11) | [23] |

| 44 | Derivative of Emodin bianthrone-hexose-malonic acid | 17.7 | 220,285,325 | 1019.2444 | 1.8 | C49H47O24 | 458.1211(100) | 502(23), 931(9), 460(4), 416(2) | [23] |

| 45 | Derivative of Emodin bianthrone-hexose-malonic acid | 17.8 | 220,280,325 | 1005.2305 | 0.1 | C48H45O24 | 458.1212(100) | 502(27), 713(21), 917(9), 961(2) | [23] |

| 46 | Phenylpropanoid-derived disaccharide esters | 18 | 220, 298,315 | 1151.3406 | −0.4 | C59H59O24 | 1151.3358(100) | 955(20), 145(5), 1133(2), 1103(2), 1009(2), 809(2) | [23] |

| 47 | Vanicoside B isomer | 18.8 | 222,298,315 | 955.2668 | −0.2 | C49H47O20 | 955.2670(100) | 145(22), 809(19), 957(16), 453(2) | [23] |

| 48 | Vanicoside B | 19.3 | 222,298,315 | 955.2662 | 0.4 | C49H47O20 | 955.2665(100) | 957(17), 809(15), 145(14), 453(1) | [16] |

| 49 | Questin | 20.2 | 222,286,313, 430 | 283.0611 | 0.4 | C16H11O5 | 240.0425(100) | 268(3) | [16] |

| 50 | Vanicoside A | 21.1 | 222,298,315 | 997.2757 | 1.5 | C51H49O21 | 997.2776(100) | 145(8), 851(5), 821(1) | [16] |

| 51 | Emodin bianthrone-hexose-malonic acid | 21.9 | 220,280,325 | 757.1752 | 2.9 | C39H33O16 | 458.1220(100) | 502(8), 713(5), 254(4), 416(2) | [23] |

| 52 | Emodin bianthrone-hexose-malonic acid | 22.6 | 220,280,325 | 757.1743 | 4.1 | C39H33O16 | 458.1214(100) | 502(10), 254(4), 713(4), 416(2) | [23] |

| 53 | Emodin | 25.4 | 221,248,267, 288,430 | 269.0455 | 0.3 | C15H9O5 | 269.0455(100) | 225(29), 241(11), 197(2), 181(1) | [16] |

| 54 | Physcion * | 29.5 | 222,266,288, 430 | 285.0757 [M − H]+ | −1.9 | C16H13O5 [M − H]+ | − | [16] |

| Analyte | λ det (nm) | Calibration Equation | n | r | Linear Range (μg/mL) | LOD (μg/mL) | LOQ (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piceid | 298 | y = 32.83x − 7.9417 | 6 | 0.9999 | 11.25−360 | 5.29 | 16.02 |

| Resveratrol | 298 | y = 60.021x − 0.4491 | 6 | 0.9998 | 1.25−40 | 1.04 | 3.16 |

| Vanicoside B | 298 | y = 26.719x − 3.8342 | 6 | 0.9999 | 4.375−140 | 1.41 | 4.28 |

| Vanicoside A | 298 | y = 34.161x − 2.9891 | 6 | 0.9995 | 0.9375−30 | 0.23 | 0.71 |

| Emodin | 298 | y = 20.389x − 2.444 | 6 | 0.9999 | 4.375−140 | 1.04 | 3.15 |

| Physcion | 298 | y = 7.1533x − 1.8287 | 6 | 0.9999 | 3.75−120 | 1.02 | 3.08 |

| Analyte | R. japonica 60% Acetone | R. japonica 40% EtOH | R. japonica 25% EtOH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/g) | %CV | (mg/g) | %CV | (mg/g) | %CV | |

| Piceid | 47.88 | 0.65 | 39.12 | 0.57 | 26.11 | 0.18 |

| Resveratrol | 1.47 | 0.71 | 3.05 | 0.69 | 3.95 | 0.26 |

| Vanicoside B | 5.67 | 0.36 | 1.77 | 0.63 | 0.30 * | 0.42 |

| Vanicoside A | 0.53 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.05 * | 2.21 |

| Emodin | 9.63 | 0.34 | 3.68 | 0.35 | 1.47 | 0.34 |

| Physcion | 7.79 | 0.78 | 0.36 * | 0.46 | 0.31 * | 0.41 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Matkowski, A.; Pitułaj, A.; Sterczała, B.; Olchowy, C.; Szewczyk, A.; Choromańska, A. In Vitro Gingival Wound Healing Activity of Extracts from Reynoutria japonica Houtt Rhizomes. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13111764

Nawrot-Hadzik I, Matkowski A, Pitułaj A, Sterczała B, Olchowy C, Szewczyk A, Choromańska A. In Vitro Gingival Wound Healing Activity of Extracts from Reynoutria japonica Houtt Rhizomes. Pharmaceutics. 2021; 13(11):1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13111764

Chicago/Turabian StyleNawrot-Hadzik, Izabela, Adam Matkowski, Artur Pitułaj, Barbara Sterczała, Cyprian Olchowy, Anna Szewczyk, and Anna Choromańska. 2021. "In Vitro Gingival Wound Healing Activity of Extracts from Reynoutria japonica Houtt Rhizomes" Pharmaceutics 13, no. 11: 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13111764

APA StyleNawrot-Hadzik, I., Matkowski, A., Pitułaj, A., Sterczała, B., Olchowy, C., Szewczyk, A., & Choromańska, A. (2021). In Vitro Gingival Wound Healing Activity of Extracts from Reynoutria japonica Houtt Rhizomes. Pharmaceutics, 13(11), 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13111764