Comparative Evaluation Model Framework for Cost-Optimal Evaluation of Prefabricated Lightweight System Envelopes in the Early Design Phase

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Link between Value for Money (VfM), Building Information Modelling (BIM), and Sustainability

1.2. Local Context

1.3. Research Gap and Aim

2. Materials and Methods

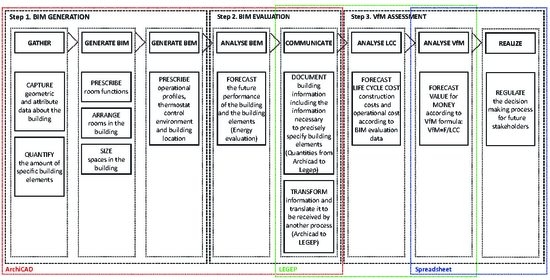

- Step 1: BIM GENERATION, gathering and generating the building data.

- Step 2: BIM EVALUATION, analysing BEM and communicating the results between tools used.

- Step 3: VfM ASSESSMENT, analysing LCC and VfM, and realizing the decision.

2.1. ECEMF—Extended Comparative Evaluation Model Framework

2.1.1. Step 1—BIM Generation.

2.1.2. Step 2—BIM Evaluation

2.1.3. Step 3—VfM Assessment

2.2. VfM and Life Cycle Costs (LCC) Methods

2.3. Financial Modelling

2.3.1. Life Cycle Period

2.3.2. Cost Planning

2.3.3. Inflation—Dynamic LCC Calculation

2.3.4. Net Present Value

2.4. Tools and Legislation

2.5. Case Study Building and System Envelopes Selection

3. Case Study

3.1. First Step-BIM Generation

3.1.1. Gather

Construction

Windows

System Envelopes

Lumar Primus System Envelope

Canopea System Envelope

Ecolar System Envelope

MED in Italy Envelope

3.1.2. Generate BIM

3.1.3. Generate Building Energy Modelling (BEM)

Building Operation Profiles

Active Technical Systems

Location, Orientation, and Climate Data

3.2. Step 2—BIM Evaluation

3.2.1. Analyse BEM—Evaluation of Energy Consumption

3.2.2. Communicate

3.3. Step 3—VfM Assessment

3.3.1. Analyse LCC—Life Cycle Cost Evaluation

3.3.2. Analyse VfM

3.3.3. Realize VfM

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Creating an extended evaluation model with functionality to enable automated workflows of evaluation is an enabler for early design optimization and decision making and this paper contributes to explaining how this can be done.

- With the use of BIM in Archicad and Legep pre-set macro-elements, the VfM evaluation is already possible in the early design phase before final detailed planning is developed, since only values of different layers of system envelopes are needed. This implicates that ECEMF can indeed be used by stakeholders in the earlier design phase.

- When looking at the functional dependence of VfM from service and repair costs, these are approximately three times higher than the maintenance costs and up to two times higher than the supply and disposal costs. This indicates that to get an accurate value for money evaluation of a building case study, it is important to asses it thorough life cycle costs and not merely supply and disposal costs that include the BEM analysis with energy-related costs.

- The ECEMF is enhancing the building’s sustainability performance by optimizing the VfM and subsequently LCC when choosing its system envelope, therefore, contributing to sustainability outcomes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- BS ISO 15686-5:2017 Buildings and Constructed Assets—Service-Life Planning. Part 5: Life-Cycle Costing. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:15686:-5:ed-2:v1:en (accessed on 5 May 2019).

- White, G.; Boyne, P. Facilities Management. In BIM and Quantity Surveying; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Far, M.S.; Duarte, C.; Pastrana, I.A. Building Information Electronic Modeling (BIM) Process as an Instrumental Tool for Real Estate Integrated Economic Evaluations. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual European Real Estate Society Conference, Istanbul, Turkey, 24–27 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer, G.; Herzog, B.; Grim, M.; Leutgöb, K. Calculating Life Cycle Cost in the Early Design Phase to Encourage Energy Efficient and Sustainable Buildings. In ECEEE 2011 Summer Study, Energy Efficiency First: The Foundation of a Low-Carbon Society; ECEEE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011; p. 1074. [Google Scholar]

- Schade, J. Life Cycle Cost Calculation Models for Buildings. Conf. Proc. 2007, 18, 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing Limited: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer-Raniga, U.; Moore, T.; Kashyap, K.; Ridley, I.; Andamon, M. Beyond Buildings: Holistic Sustainable Outcomes for University Buildings. In Proceedings of the 15th International Australasian Campuses towards Sustainability (ACTS) Conference, Geelong, Australia, 21–23 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oyedele, L.; Tham, K.; Fadeyi, M.; Jaiyeoba, B. Total Building Performance Approach in Building Evaluation: Case Study of an Office Building in Singapore. J. Energy Eng. 2012, 138, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryghaug, M.; Sørensen, K.H. How Energy Efficiency Fails in the Building Industry. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, M.; Fabrizio, E.; Virgone, J.; Filippi, M. Energy Systems in Cost-Optimized Design of Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings. Autom. Constr. 2016, 70, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, M.; Mukkavaara, J.; Shadram, F.; Olofsson, T. Multidisciplinary Optimization of Life-Cycle Energy and Cost Using a BIM-Based Master Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.; Liu, J.; Matthews, J.; Sing, C.; Smith, J. Future Proofing PPPs: Life-Cycle Performance Measurement and Building Information Modelling. Autom. Constr. 2015, 56, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Tang, W.; Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, T.; Shen, W.; Huang, M.; Zhou, Y. Enhancing Engineer–Procure–Construct Project Performance by Partnering in International Markets: Perspective from Chinese Construction Companies. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HM Treasury. Value for Money Assessment Guidance; HM Treasury: London, UK, 2006; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande, A.; Azhar, S.; Amireddy, S. A Framework for a BIM-Based Knowledge Management System. Procedia Eng. 2014, 85, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basbagill, J.; Flager, F.; Lepech, M. A Multi-Objective Feedback Approach for Evaluating Sequential Conceptual Building Design Decisions. Autom. Constr. 2014, 45, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About ARCHICAD—A 3D Architectural BIM Software for Design & Modeling. Available online: http://www.graphisoft.com/archicad/ (accessed on 6 January 2016).

- Motawa, I.; Carter, K. Sustainable BIM-Based Evaluation of Buildings. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 74, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Li, H. BIM Based Value for Money Assessment in Public-Private Partnership. In Collaboration in a Data-Rich World; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Grilo, A.; Jardim-Goncalves, R. Challenging Electronic Procurement in the AEC Sector: A BIM-Based Integrated Perspective. Autom. Constr. 2011, 20, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis Langdon Management Consulting. Life Cycle Costing (LCC) as a Contribution to Sustainable Construction, Guidance on the Use of the LCC Methodology and Its Application in Public Procurement; Davis Langdon Management Consulting: London, UK, 2007; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter, A.; Thesseling, F. Building Information Model Based Energy/Exergy Performance Assessment in Early Design Stages. Autom. Constr. 2009, 18, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavrl, M.Š.; Gjerkeš, H.; Tomšič, M. Integration of Nearly Zero Energy Buildings in Sustainable Networks—A Challenge for Sustainable Building Stock. In Proceedings of the World Engineering Forum, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 17–21 September 2012; p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Glušič, A. Pravilnik o Energetski Učinkovitosti Stavb (Regulation on the Energy Performance of Buildings). Available online: http://www.enforce-een.eu/slo/pures-2010/pravilnik-o-energetski-ucinkovitosti-stavb (accessed on 26 September 2013).

- Lewandowska, A.; Branowski, B.; Joachimiak-Lechman, K.; Kurczewski, P.; Selech, J.; Zablocki, M. Sustainable Design: A Case of Environmental and Cost Life Cycle Assessment of a Kitchen Designed for Seniors and Disabled People. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Na, Y. Comparative Analysis of Energy Related Performance and Construction Cost of the External Walls in High-Rise Residential Buildings. Energy Build. 2015, 99, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Vuolle, M.; Sirén, K. Minimisation of Life Cycle Cost of a Detached House Using Combined Simulation and Optimisation. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 2022–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leckner, M.; Zmeureanu, R. Life Cycle Cost and Energy Analysis of a Net Zero Energy House with Solar Combisystem. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matic, D.; Calzada, J.; Eric, M.; Babin, M. Economically Feasible Energy Refurbishment of Prefabricated Building in Belgrade, Serbia. Energy Build. 2015, 98, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluch, P.; Baumann, H. The Life Cycle Costing (LCC) Approach: A Conceptual Discussion of Its Usefulness for Environmental Decision-Making. Build. Environ. 2004, 39, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molavi, J.; Barral, D. A Construction Procurement Method to Achieve Sustainability in Modular Construction. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Modular Fabrication. ASST. Available online: http://www.asst.com/tag/modular-fabrication/ (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- Norton, B.; McElligott, W. Value Management in Construction; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1995; pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Akintoye, A.; Hardcastle, C. VFM and Risk Allocation Models in Construction PPP Projects, Public Private Partnership. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Built and Natural Environment, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, UK, 2001; pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Building Sciences. NBIMS, National Building Information Model Standard Version 1.0—Part 1: Overview, Principles, and Methodologies; National Institute of Building Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji, S.; Olawumi, T.; Awodele, O. Achieving Value for Money (VFM) In Construction Projects. Civ. Environ. Res. 2017, 9, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider, R.; Messner, J. The Uses of BIM: Classifying and Selecting BIM Uses; Version 0.9; The Pennsylvania State University: State College, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- RICS: RICS Valuation—Professional Standards January 2014; Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors: London, UK, 2014.

- Cost Model: Value for Money. Available online: http://www.building.co.uk/cost-model-value-for-money/1348.article (accessed on 18 November 2011).

- Dallas, M. Value and Risk Management; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Rangelova, F.; Traykova, M. Project Management in Construction. In Proceedings of the First Scientific-Applied Conference with International Participation, Project Management in Construction, Sofia, Bulgaria, 4–5 December 2014; pp. 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Hafner, A.; Schäfer, S.; Krause, K. Environmental footprint of timber buildings and the implementation in city planning. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE 2016), Vienna, Austria, 22–25 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- König, H. Lebenszyklusanalyse von Wohngebäuden, Lebenszyklusanalyse mit Berechnung der Ökobilanz und Lebenszykluskosten; Ascona GbR: Gröbenzell, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, L.; Gu, D.; Lin, B.; Huang, M.; Gai, J.; Zhu, Y. Life Cycle Green Cost Assessment Method for Green Building Design. Proc. Build. Simul. IBPSA 2007, 1962, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- SURS. Available online: http://www.stat.si/statweb (accessed on 12 December 2015).

- Koenig, H. LEGEP-Handbuch für die Gebäudezertifizierung; Weka Media: Kissing, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vogdt, F.; Kochendörfer, B.; Dittmar, A. Analyse Und Vergleich Energetischer Standards Anhand Eines Exemplarischen Einfamilienhauses Bzgl. Energiebedarf Und Kosten Über Den Lebenszyklus. Bauphysik 2010, 32, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, C.; Kretlow, W.; McGuigan, J. Contemporary Financial Management, 12th ed.; South-Western Publishing Co.: Winsted, CT, USA, 2011; pp. 147–498. [Google Scholar]

- Kruschwitz, L. Investitionsrechnung, 11th ed.; Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag: Munich, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nachhaltigkeit im Wohnungsbau—NaWoh—Home. Available online: http://www.nawoh.de (accessed on 4 March 2017).

- Zavrl, M.Š. Vseživljenjsko Vrednotenje Stroškov Pri Obnovi Stavb. Energija v Stavbah 2015, 4. Available online: http://www.gi-zrmk.si/media/uploads/public/document/173-lcca_save_sl.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2019).

- Spletna Trgovina SIST. Available online: http://ecommerce.sist.si/catalog/ (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- König, H.; Schmidberger, E.; Cristofaro, L. Life Cycle Assessment of a Tourism Resort with Renewable Materials and Traditional Construction Techniques; Portugal SB07, Sustainable Construction, Materials and Practice; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 1043–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, N.; Wagner, A.; Luetzkendorf, T.; König, H. Life cycle assessment of passive buildings with legep®—A LCA-Tool from Germany. In Proceedings of the 2005 World Sustainable Building Conference, Tokyo, Japan, 27–29 September 2005; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- NaWoh Steckbrief mit Teilindikatoren, Ökonomische Qualität, Lebenszykluskosten (LCC), Ausgewählte Kosten im Lebenszyklus. Available online: http://www.nawoh.de/uploads/pdf/kriterien/v_3_0/Oekonomische_Qualitaet_V_3_0.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2018).

- Surveying and Mapping Authority of the Republic of Slovenia. Annual Report on the Slovenian Property Market for 2014; Surveying and Mapping Authority of the Republic of Slovenia: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2015; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Dolenc, D. Gospodinjstva in Družine, Slovenija, 1 January 2018. Available online: https://www.stat.si/StatWeb/News/Index/7725 (accessed on 21 August 2019).

- Solar Decathlon 2012 Documentación Técnica. Solar Decathlon Europe. Available online: http://www.sdeurope.org/downloads/sde2012 (accessed on 20 October 2013).

- Best Buy Award—Drugič Zapored z Najboljšim Razmerjem Med Ceno in Kakovostjo. Available online: http://www.lumar.si/novica.asp?ID=152 (accessed on 18 November 2015).

- Predstavili Bodo Najbolje Prodajano Hišo Primus. Available online: http://www.finance.si/8818940/Predstavili-bodo-najbolje-prodajano-hišo-Primus (accessed on 15 May 2015).

- Slovenian Environmental Public Fund. Available online: https://www.ekosklad.si/dokumenti/rd/29SUB-OB15/Seznam_okna.xls (accessed on 21 August 2019).

- Ministrstvo za Okolje in Prostor. Tehnična Smernica TSG-1-004:2010 Učinkovita Raba Energije; Ministrstvo za Okolje in Prostor: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Primus se Predstavi. Available online: http://www.lumar.si/novica.asp?ID=106 (accessed on 5 May 2014).

- Staib, G.; Dörrhöffe, A.; Rosenthal, M. Components and Systems, Modular Construction—Design, Structure, New Technologies; Birkhäuser: Munich, Germany, 2008; pp. 10–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lumar Pasiv Energy. Available online: https://www.lumar.si/konstrukcijski-sistemi_2017_pasiv-energy.html?phpMyAdmin=25d4dda21d1770ec1efe0cc63d777e6b (accessed on 3 February 2017).

- Team Rhone-Alpes: Project Manual #5, iSolar Decathlon Europe 2012 Technical Resources. Available online: http://www.sdeurope.org/downloads/sde2012/ (accessed on 20 October 2013).

- Team Ecolar: Jury Reports, Solar Decathlon Europe 2012 Technical Resources. Available online: http://www.sdeurope.org/downloads/sde2012/ (accessed on 20 October 2013).

- MED Team, Deliverable #7, Solar Decathlon Europe 2012 Technical Resources. Available online: http://www.sdeurope.org/downloads/sde2012/ (accessed on 20 October 2013).

- Statistical Office of Republic Slovenia, Naseljena Stanovanja, Slovenija, 1 January 2011—Začasni Podatki (Households, Slovenia, 1 January 2011—Interim Data). Available online: http://www.stat.si/StatWeb/glavnanavigacija/podatki/prikazistaronovico?IdNovice=4420 (accessed on 12 March 2016).

- EcoDesigner STAR User Manual; GRAPHISOFT: Budapest, Hungary, 2014.

- Zelo Dobre Nizkoenergijske Hiše—Optimirane za Pridobitev Subvencije Eko Sklada. Available online: http://www.lumar.si/energetski-koncepti.asp?m3=21 (accessed on 12 October 2015).

| Life cycle cost calculation according to NaWoh 4.1.1. | 2.4.1 Selected construction costs according to DIN 276 | 2.4.2 Selected user costs according to DIN 18960 | |||||||

| 2.4.2.1 KG 300 according to DIN 18960: Selected operational costs | 2.4.2.2 KG 400 according to DIN 18960: Repair costs | ||||||||

| 300 + 400 Building construction + Technical Building Equipment | KG 310 according to DIN 18960: Selected supply costs (energy and water) | KG 320 according to DIN 18960: Wastewater disposal | KG 330 according to DIN 18960: Cleaning of buildings | KG 350 according to DIN 18960: Operation, inspection and maintenance | KG 410 according to DIN 18960: Repair of the building constructions | KG 420 according to DIN 18960: Repair of the technical building equipment | |||

| Cost categories | Construction | Energy | Water | Wastewater | Cleaning | Maintenance | Replacement investment | Regular repair | Replacement investment |

| System Envelope | Material | T (mm) | S (mm) | U (W/m2 K) | Material | T (mm) | Sum (mm) | U (W/m2 K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wall | Roof | |||||||

| Lumar Primus | Plaster Thin | 2 | 365 | 0.119 | Polyethylene waterproofing membrane | 2 | 365 | 0.119 |

| Plaster reinforcement | 3 | Mineral inclined insulation | 300 | |||||

| Mineral insulation wool | 100 | bitumen vapor barrier | ||||||

| Plasterboard | 15 | OSB panel | 18 | |||||

| Cellulose insulation & (Laminated spruce studs) | 160 | Laminated spruce beams | 60/240 | |||||

| Vapor barrier | 0.2 | timber under construction | 70/22 | |||||

| Mineral wool insulation & (timber studs 60/80) | 60 | Plasterboard | 12.5 | |||||

| Plasterboard | 15 | |||||||

| Plasterboard | 10 | |||||||

| Wall | Roof | |||||||

| Canopea | Plaster Thin | 2 | 344 | 0.08 | Polyethylene waterproofing membrane | 2 | 370 | 0.07 |

| Plaster reinforcement | 3 | Wood joist + cellulose insulation | 60 | |||||

| Kerto-Q LVL panel | 27 | Kerto-Q LVL panel | 25 | |||||

| Cellulose insulation & (1/2 IPE200 and timber battens 60x40) | 200 | cellulose insulation (timber 130/60) | 130 | |||||

| OSB panel | 12 | Kerto-Q LVL panel | 25 | |||||

| Vacuum insulation | 30 | Vacuum insulation (timber 45/45) | 45 | |||||

| Vapor barrier | 0.2 | Vapor barrier | 0.2 | |||||

| Proliferated steel rails | 35 × 35 | Cellulose insulation (timber 60/40) | 60 | |||||

| Fibralith panel | 25 | Reflective insulating screen | 10 | |||||

| Earth coatin | 10 | Plasterboard | 12.5 | |||||

| Earth paintwork (Akterre) | 3 | |||||||

| Wall | Roof | |||||||

| Ecolar | Lucido system | 56 | 273 | 0.10 | Polyethylene waterproofing membrane | 2 | 366 | 0.13 |

| MDF board | 15 | OSB | 15 | |||||

| Thermo-Hemp WCG + Lignotrend U*PSI t 6/170 | 170 | Thermo-Hemp WCG 038 & (timber 160/60) | 160 | |||||

| OSB panel | 19 | Thermo-Hemp WCG38 +Lignotrend | 135 | |||||

| Plasterboard | 12.5 | Vapor barrier | 0.2 | |||||

| Clay board | 25 | |||||||

| Plasterboard | 12.5 | |||||||

| Wall | Roof | |||||||

| MED in Italy | Plaster Thin | 2 | 493 | 0.14 | Stamisol Pack 500 | 0.7 | 386 | 0.14 |

| Plaster reinforcement | 3 | Pavatex Isolair L | 22 | |||||

| Pavatherm Plus | 100 | Pavatherm Plus | 80 | |||||

| OSB | 15 | OSB | 18 | |||||

| Pavaflex & (timber battens 200/60) | 200 | Pavatex & (timber battens 200/80) | 200 | |||||

| Plasterboard panel | 12.5 | OSB | 18 | |||||

| Aluminum pipes (round) + wet sand | 80 | Cork | 20 | |||||

| Timber battens 60/60 | 60 | Gypsum Fiberboard (Farmacell) | 27 | |||||

| Solid wood panel | 20 | |||||||

| System Envelope | Average U-Value (W/m2 K) | Heating (kWh/a) | Service Hot Water (kWh/a) | Cooling (kWh/a) | Light. And Equip. (kWh/a) | Net Heating Value (kWh/m2 a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumar Pr. | 0.31 | 3103.6 | 2765.3 | 355.8 | 2366.0 | 36.33 |

| Canopea | 0.28 | 2653.6 | 2765.3 | 314.2 | 2230.0 | 31.53 |

| Ecolar | 0.31 | 2991.3 | 2765.3 | 346.6 | 2331.0 | 35.00 |

| MED | 0.31 | 3167.6 | 2765.3 | 274.0 | 2348.0 | 35.80 |

| Lumar Primus | Canopea | Ecolar | MED in Italy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| building construction (300) in € | 80,211.61 | 90,937.44 | 115,963.85 | 88,176.44 |

| foundation | 14,495.04 | 14,495.04 | 14,495.04 | 14,495.04 |

| floor slab | 6480.82 | 6480.82 | 6480.82 | 6480.82 |

| exterior wall with windows and shading in € | 44,378.86 | 48,123.12 | 74,856.15 | 50,676.33 |

| >Windows | 14,437.84 | 14,437.84 | 14,437.84 | 14,437.84 |

| >Shading | 6631.26 | 6631.26 | 6631.26 | 6631.26 |

| interior walls | 6655.14 | 6655.14 | 6655.14 | 6655.14 |

| roof in € | 7402.43 | 14,589.82 | 12,849.40 | 9069.79 |

| technical equipment (400) in € | 28,552.62 | 28,523.47 | 28,523.47 | 28,523.47 |

| Construction cost net in EUR (300 and 400) in € | 108,764.67 | 119,459.53 | 144,487.68 | 116,728.76 |

| Difference (%) | 0 | +8.9 | +24.7 | +6.8 |

| System Envelope | Supply and Disposal in EUR | Diff. in Supply and Disposal in (%) | Cleaning Cost in EUR | Diff. in Cleaning (%) | Maintan. Cost in EUR | Diff. in Maintan. (%) | Service and Repair Cost (KG300/400) in EUR | Diff. in Service and Repair Cost (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumar Pr. | 16,718.39 | 0 | 5792.52 | 0 | 16,747.35 | 0 | 43,792.02 | 0 |

| Canopea | 16,214.44 | −3.11 | 5792.52 | 0 | 17,011.07 | 1.57 | 45,883.56 | 4.78 |

| Ecolar | 16,634.80 | −0.5 | 11,266.79 | 94.51 | 17,625.88 | 5.25 | 58,794.84 | 34.26 |

| MED | 16,674.43 | −0.26 | 5792.52 | 0 | 16,952.89 | 1.23 | 50,046.58 | 14.28 |

| System Envelope | Const. Cost Net in EUR (300 and 400) Building Construction (300) and Technical Installations (400) | Operational Cost (NaWoh) in EUR | Diff. in Operational Cost in % | LCC (Const. Cost Net 300 and 400 + Operational Cost NaWoh) in EUR | Diff. in LCC in % | Value for Money in % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumar Pr. | 108,764.67 | 83,060.28 | 0 | 191,824.95 | 0 | 100 |

| Canopea | 119,459.53 | 84,901.59 | +02.17 | 204,361.12 | +06.13 | 94 |

| Ecolar | 144,487.68 | 104,322.31 | +20.40 | 248,809.99 | +22.90 | 77 |

| MED | 116,728.76 | 89,466.42 | +07.16 | 206,195.18 | +06.97 | 93 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jausovec, M.; Sitar, M. Comparative Evaluation Model Framework for Cost-Optimal Evaluation of Prefabricated Lightweight System Envelopes in the Early Design Phase. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185106

Jausovec M, Sitar M. Comparative Evaluation Model Framework for Cost-Optimal Evaluation of Prefabricated Lightweight System Envelopes in the Early Design Phase. Sustainability. 2019; 11(18):5106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185106

Chicago/Turabian StyleJausovec, Marko, and Metka Sitar. 2019. "Comparative Evaluation Model Framework for Cost-Optimal Evaluation of Prefabricated Lightweight System Envelopes in the Early Design Phase" Sustainability 11, no. 18: 5106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185106

APA StyleJausovec, M., & Sitar, M. (2019). Comparative Evaluation Model Framework for Cost-Optimal Evaluation of Prefabricated Lightweight System Envelopes in the Early Design Phase. Sustainability, 11(18), 5106. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185106