Processes of Participation in the Development of Urban Food Strategies: A Comparative Assessment of Exeter and Eindhoven

Abstract

:1. Introduction

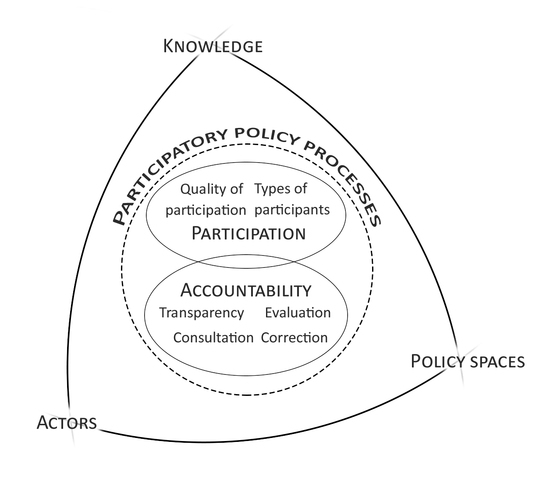

2. Participation

3. Operationalizing Participatory Policy Processes

4. Methods

5. Results

5.1. The Exeter Food Network

5.2. Proeftuin040, Eindhoven

5.3. Comparison of Participatory Policy Processes

5.3.1. Participation

5.3.2. Accountability

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinrichs, C.C. Transitions to sustainability: A CHANGE in thinking about food systems change? Agric. Hum. Values 2014, 31, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbeling, M.; Zeeuw, H.; Veenhuizen, R. Municipal Policies and Programmes on Urban Agriculture: Key Issues and Possible Courses of Action. In Cities, Poverty and Food: Multi-Stakeholder Policy and Planning in Urban Agriculture; De Zeeuw, H., Dubbeling, M., van Veenhuizen, R., Eds.; RUAF Foundation and Practical Action Publishers: Warwickshire, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Prosperi, P.; Moragues-Faus, A.; Sonnino, R.; Devereux, C. Measuring Progress towards Sustainable Food Cities: Sustainability and Food Security Indicators; Report of the ESRC Financed Project “Enhancing the Impact of Sustainable Urban Food Strategies. Available online: http://sustainablefoodcities.org/Portals/4/Documents/Measuring%20progress%20towards%20sustainable%20food%20cities_final%20report%20w%20appendixes.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2016).

- Morgan, K.J. Feeding the City: The Challenge of Urban Food Planning. Int. Plan. Stud. 2009, 14, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothukuchi, K.; Kaufman, J.L. Placing the food system on the urban agenda: The role of municipal institutions in food systems planning. Agric. Hum. Values 1999, 16, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPES Food. The New Science of Sustainable Food Systems: Overcoming Barriers to Food Systems Reform; First Report of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems; The International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES Food): Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tendall, D.M.; Joerin, J.; Kopainsky, B.; Edwards, P.; Shreck, A.; Le, Q.B.; Kruetli, P.; Grant, M.; Six, J. Food system resilience: Defining the concept. Glob. Food Secur. 2015, 6, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericksen, P.J. What is the vulnerability of a food system to global environmental change? Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J. A food systems approach to researching food security and its interactions with global environmental change. Food Secur. 2011, 3, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Stuart Chapin, F.; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FAO Statistical Yearbook; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wiskerke, J.S.C.C. Urban food systems. In Cities and Agriculture: Developing Resilient Urban Food Systems; De Zeeuw, H., Drechsel, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, T.; Escudero, A.G. City Regions as Landscapes for People, Food and Nature; EcoAgriculture Partners, on Behalf of the Landscapes for People, Food and Nature Initiative: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; RUAF. A Vision for City Region Food Systems—Building Sustainable and Resilient City Regions; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Thrift, N. Looking through the city. In Seeing Like a City; Amin, A., Thrift, N., Eds.; Polity Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.R. If Mayors Ruled the World: Why Cities Can and Should Govern Globally and How They Already Do by; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, K.; Anderberg, S.; Coenen, L.; Neij, L. Advancing sustainable urban transformation. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey Global Institute. Urban world: Mapping the economic power of cities. J. Monet. Econ. 2011, 36, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfram, M. Conceptualizing urban transformative capacity: A framework for research and policy. Cities 2016, 51, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Culture, Urban, Future—Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban Development; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Milan Expo. Milan Urban Food Policy Pact; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Milan, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moragues, A.; Morgan, K.; Moschitz, H.; Neimane, I.; Nilsson, H.; Pinto, M.; Rohracher, H.; Ruiz, R.; Thuswald, M.; Tisenkopfs, T.; et al. Urban Food Strategies: The Rough Guide to Sustainable Food Systems; Foodlinks: Rochester, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, K.; Campbell, M.C.; Bailkey, M. Urban Agriculture: Growing Healthy, Sustainable Places; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011; pp. 1–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Food Cities. Developing a Food Plan; Bristol City Council: Bristol, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, A.; Ward, K. Researching the geographies of policy mobility: Confronting the methodological challenges. Environ. Plan. A 2012, 44, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, R. Unpacking Policy: Actors, Knowledge and Spaces. In Unpacking Policy: Knowledge, Actors, and Spaces in Poverty Reduction in Uganda and Nigeria; Brock, K., McGee, R., Gaventa, J., Eds.; Fountain Pub Ltd.: Amenia, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- De Zeeuw, H.; Dubbeling, M. Process and tools for multi-stakeholder planning of the urban agro-food system. In Cities and Agriculture–Developing Resilient Urban Food Systems; De Zeeuw, H., Drechsel, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 56–87. [Google Scholar]

- Amerasinghe, P.; Cofie, O.O.; Larbi, T.O.; Drechsel, P. Facilitating Outcomes: Multi-Stakeholder Processes for Influencing Policy Change on Urban Agriculture in Selected West African and South Asian Cities; IWMI Research Report 153; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bexell, M.; Tallberg, J.; Uhlin, A. Democracy in global governance: The promises and pitfalls of transnational actors. Glob. Gov. 2010, 16, 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa, J. Strengthening Participatory Approaches to Local Governance: Learning the Lessons from Abroad. Natl. Civ. Rev. 2004, 93, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, A.; Long, N. Anthropology, Development, and Modernities: Exploring Discourses, Counter-tendencies, and Violence; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. Displacement, development, and modernity in the Colombian Pacific. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2003, 55, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R. Whose Reality Counts? Putting the First Last, 2nd ed.; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, A.; Brock, K. What Do Buzzwords Do for Development Policy? A Critical Look at “Participation”, “Empowerment” and “Poverty Reduction”. Third World Q. 2005, 26, 1043–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, H. Participation and accountability at the periphery: Democratic local governance in six countries. World Dev. 2000, 28, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, J.; Chambers, R.; Gaventa, J. Mainstreaming Participation in Development. In Making Development Work; Hanna, N., Picciotto, R., Eds.; Transaction: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney, P. The Politics of Evidence-Based Policy Making, 1st ed.; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, B.; Hebinck, P. In the Shadow of Policy–Everyday Practices in South Africa’s Land and Agrarian Reform; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa, J. Exploring citizenship, participation and accountability. IDS Bull. 2000, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, I.; Nainan, N. “Negotiated spaces” for representation in Mumbai: Ward committees, advanced locality management and the politics of middle-class activism. Environ. Urban. 2008, 20, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholte, J.A. Building Global Democracy? Civil Society and Accountable Global Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barling, D.; Duncan, J. The dynamics of the contemporary governance of the world’s food supply and the challenges of policy redirection. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willetts, P. Non-Governmental Organizations in World Politics: The Construction of Global Governance; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp, J. Food, 2nd ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Ploeg, J.D. The food crisis, industrialized farming and the imperial regime. J. Agrar. Chang. 2010, 10, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckstrand, K. Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Rethinking legitimacy, accountability and effectiveness. Eur. Environ. 2006, 16, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J. Global Food Security Governance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Warshawsky, D.N. Civil society and public–Private partnerships: Case study of the Agri-FoodBank in South Africa. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2015, 17, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, A. Locating citizen Participation. IDS Bull. 2002, 32, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, M. Bridging the Gap in the Dutch Participation Society. Etnofoor Particip. 2014, 26, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Polk, M.; Knutsson, P. Participation, value rationality and mutual learning in transdisciplinary knowledge production for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansbridge, J. On the Idea that Participation Makes Better Citizens. In Citizen Competence and Democratic Institutions; Elkin, S., Soltan, K.E., Eds.; The Pennsylvania State University Press: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, T.; Franklin, A. Replacing neoliberalism: Theoretical implications of the rise of local food movements. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, F. The Context: Multi-stakeholder Processes and Global Governance. In Multi-stakeholder Processes for Governance and Sustainability; Hemmati, M., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pijnenburg, B. Keeping It Vague: Discourses and Practices of Participation in Rural Mozambique. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati, M. Multi-Stakeholder Processes for Governance and Sustainability; Earthscan: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, L.; Karpouzoglou, T.; Doshi, S.; Frantzeskaki, N. Organising a safe space for navigating social-ecological transformations to sustainability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6027–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebinck, A.; Villarreal, G. “Local” level analysis of FNS pathways in the Netherlands: Two case studies, Urban Agricultural Initiatives and the Food Bank. TRANSMANGO: EU KBBE.2013.2.5-01 Grant Agreement No: 613532. 2016. Available online: http://transmango.eu/userfiles/update%2009112016/reports/5%20the%20netherlands%20report.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2016).

- Vervoort, J.; Helfgott, A.; Lord, S. D3.2 Scenarios Methodology Framework and Training Guide. TRANSMANGO: EU KBBE.2013.2.5-01 Grant Agreement No: 613532. 2016. Available online: http://www.transmango.eu/userfiles/update%2009112016/transmango%20d3.2%20scenarios%20training%20guide.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- ONS. Population Estimates for UK Mid-2014 Analysis Tool; Office for National Statistics: Newport, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lobley, M.; Thomson, J.T.; Barr, D. A Review of Devon’s Food Economy; CRPR Research Report No. 34; Centre for Rural Policy Research: Exeter, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rydin, Y.; Natarajan, L. The materiality of public participation: The case of community consultation on spatial planning for. Int. J. Justice Sustain. 2015, 21, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, M.; Scoones, I.; Stirling, A. Dynamic Sustainabilities: Technology, Environment, Social Justice; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| The Exeter Food Network | Proeftuin040, Eindhoven | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Participation | Types of participants and their relationships to one and another |

|

|

| Quality of Participation in the participatory process |

|

| |

| Accountability | Transparency on actions and used resources |

|

|

| Consultation of those that are about to be affected |

|

| |

| Evaluation of impacts and effects |

|

| |

| Correction when actions have had harmful effects |

|

| |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hebinck, A.; Page, D. Processes of Participation in the Development of Urban Food Strategies: A Comparative Assessment of Exeter and Eindhoven. Sustainability 2017, 9, 931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060931

Hebinck A, Page D. Processes of Participation in the Development of Urban Food Strategies: A Comparative Assessment of Exeter and Eindhoven. Sustainability. 2017; 9(6):931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060931

Chicago/Turabian StyleHebinck, Aniek, and Daphne Page. 2017. "Processes of Participation in the Development of Urban Food Strategies: A Comparative Assessment of Exeter and Eindhoven" Sustainability 9, no. 6: 931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060931

APA StyleHebinck, A., & Page, D. (2017). Processes of Participation in the Development of Urban Food Strategies: A Comparative Assessment of Exeter and Eindhoven. Sustainability, 9(6), 931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060931