Estimating Rainfall Interception of Vegetation Canopy from MODIS Imageries in Southern China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Rainfall Data

2.2.2. Leaf Area Index (LAI) Data

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Canopy Rainfall Interception Model

2.3.2. Canopy Rainfall Interception Rate (CRIR)

2.3.3. Propensity Score Analysis

2.3.4. Categorization of Canopy Rainfall Interception

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Spatiotemporal Variation Pattern of Rainfall

3.2. Spatiotemporal Variation Patterns of LAI

3.3. Spatiotemporal Variation Pattern of Rainfall Interception

3.3.1. Variation Pattern of Annual Canopy Rainfall Interception

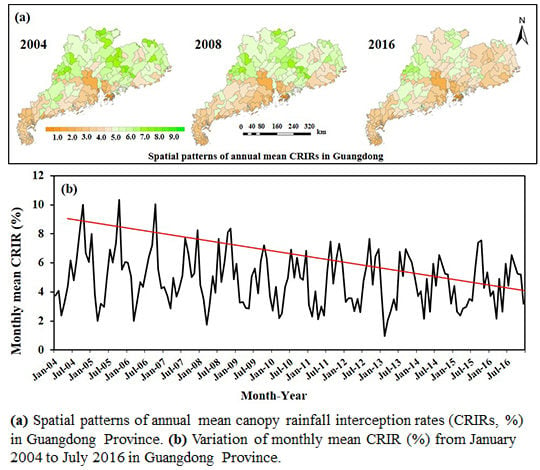

3.3.2. Variation Patterns of Annual CRIR

3.4. Effects of Climate and Forest Cover on Variation Patterns of the CRIR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Savenije, H.H.G. The importance of interception and why we should delete the term evapotranspiration from our vocabulary. Hydrol. Proc. 2004, 18, 1507–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdos, F.V.; Álvarez, C.; García, A.; Revilla, J.A. Estimated distributed rainfall interception using a simple conceptual model and Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS). J. Hydrol. 2012, 468–469, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S. A proposal for a new forest canopy interception mechanism: Splash droplet evaporation. J. Hydrol. 2006, 319, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiko, C.T.; Makurira, H.; Gerrits, A.M.J.; Savenije, H.H.G. Measuring forest floor and canopy interception in a savannah ecosystem. Phys. Chem. Earth 2012, 47–48, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.Y.; Li, W.; Wu, X.C.; Shi, F.Z.; Fang, W.W.; Pei, T.T. Modeling rainfall interception loss by two xerophytic shrubs in the Loess Plateau. Hydrol. Process. 2017, 31, 1926–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzylo, A.; Llorens, P.; Valente, F.; Keizer, J.J.; Domingo, F.; Gash, J.H.C. A review of rainfall interception modelling. J. Hydrol. 2009, 370, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunkerley, D. Intra-storm evaporation as a component of canopy interception loss in dryland shrubs: Observations from Fowlers Gap, Australia. Hydrol. Process. 2008, 22, 1985–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, Y.; Komatsu, H.; Kuramoto, K.; Otsuki, K. Characteristics of canopy interception loss in moso bamboo forests of Japan. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 27, 2041–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlyle-Moses, D.E.; Laureano, J.F.; Price, A.G. Throughfall and throughfall spatial variability in Madrean oak forest communities of northeastern Mexico. J. Hydrol. 2014, 297, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holwerda, F.; Scatena, F.N.; Bruijnzeel, L.A. Throughfall in a Puerto Rican lower montane rainforest: A comparison of sampling strategies. J. Hydrol. 2006, 327, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuartas, L.A.; Tomasella, J.; Nobre, A.D.; Hodnett, M.G.; Waterloo, M.J.; Múnera, J.C. Interception water-partitioning dynamics for a pristine rainforest in Central Amazonia: Marked differences between normal and dry years. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2007, 145, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.L.; Rolfe, G.L. Determining sample size in throughfall studies. For. Sci. 1979, 25, 582–584. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Estimation of rainfall storage capacity in the canopies of cypress wetlands and slash pine uplands in North-Central Florida. J. Hydrol. 1998, 207, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguchi, A.; Hattori, S.; Park, H.T. The influence of seasonal changes in canopy structure on interception loss: Application of the revised Gash model. J. Hydrol. 2006, 318, 80–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.H.; Zhao, C.Y.; Shen, W.H.; Xu, Z.L.; Feng, Z.D. Modeling canopy interception of Picea Crassifolia forest in Qilian mountains using QuickBird satellite data. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Cape Town, South Africa, 12–17 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.K.; Zhao, P.; Yan, B.Y.; Xie, H.J.; Yu, P.T.; Wan, W.; Fan, W.; Hong, Y. Developing the Remote Sensing-Gash analytical model for estimating vegetation rainfall interception at very high resolution: A case study in the Heihe river basin. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, F.; Sanchez, G.; Mor, M.J.; Brenner, A.J.; Puigdefábregas, J. Measurement and modelling of rainfall interception by three semi-arid canopies. Agr. For. Meteorol. 1998, 91, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dijk, A.I.J.M.V.; Gash, J.H.; van Gorsel, E.; Blanken, P.D.; Cescatti, A.; Emmel, C.; Gielen, B.; Harman, I.N.; Kiely, G.; Merbold, L.; et al. Rainfall interception and the coupled surface water and energy balance. Agr. For. Meteorol. 2015, 214–215, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringham, T.K.; Snyder, K.A.; Snyder, D.K.; Lossing, S.S.; Carr, C.A.; Stringham, B.J. Rainfall Interception by Single leaf Piñon and Utah Juniper: Implications for Stand-Level Effective Precipitation. Rangeland Ecol. Manag. 2018, 71, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, A.J.; Morton, A.J. A predictive model of rainfall interception in forests: III. Sensitivity of the model to stand parameters and meteorological variables. J. Appl. Ecol. 1977, 14, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, A.J.; Morton, A.J.; Robins, P.C. A predictive model of rainfall interception in forests. II. Generalization of the model and comparison with observations in some coniferous and hardwood stand. J. Appl. Ecol. 1975, 12, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gash, J.H.C.; Lloyd, C.R.; Lachaud, G. Estimating sparse forest rainfall interception with an analytical model. J. Hydrol. 1995, 170, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gash, J.H.C.; Morton, A.J. An application of the Rutter model to the estimation of the interception loss from Thetford Forest. J. Hydrol. 1978, 38, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.M.M.; Attarod, P.; Van Stan, J.T.; Pypker, T.G.; Dunkerley, D. Efficiency of the reformulated Gash’ interception model in semiarid afforestations. Agr. For. Meteorol. 2015, 201, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkerley, D. Measuring interception loss and canopy storage in dryland vegetation: A brief review and evaluation of available research strategies. Hydrol. Process. 2000, 14, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levia, D.F.; Frost, E.E. A review and evaluation of stemflow literature in the hydrologic and biogeochemical cycles of forested and agricultural ecosystems. J. Hydrol. 2003, 274, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.P.; Zhang, Y.F.; Wang, Z.N.; Pan, Y.X.; Hu, R.; Li, X.J.; Zhang, H. Influence of shrub canopy morphology and rainfall characteristics on stemflow within a revegetated sand dune in the Tengger Desert, NW China. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 27, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, S.M.; Jetten, V.G. Estimating spatial patterns of rainfall interception from remotely sensed vegetation indices and spectral mixture analysis. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2007, 21, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delegido, J.; Fernandez, G.; Gandia, S.; Moreno, J. Retrieval of chlorophyll content and the LAI of crops using hyperspectral techniques: Applications of PROBA/CHRIS data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2008, 29, 7107–7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunetta, R.S.; Johnson, D.M.; Lyon, J.G.; Crotwell, J. Impacts of imagery temporal frequency on land-cover change detection monitoring. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 89, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S. Application of three canopy interception models to a young stand of Japanese cypress and interpretation in terms of interception mechanism. J. Hydrol. 2007, 342, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Zhao, C.; Feng, Z.; Xu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Y. Canopy interception by a spruce forest in the upper reach of Heihe River basin, Northwestern China. Hydrol. Process. 2014, 28, 1734–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, C.P.; Bruijnzeel, L.A.; Lubczynski, M.W.; Ravelona, M.; Zwartendijk, B.W.; van Meerveld, H.J.I. Measurement and modelling of rainfall interception by two differently aged secondary forests in upland Eastern Madagascar. J. Hydrol. 2017, 545, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, X.; Vejre, H. Spatiotemporal patterns and characteristics of remotely sensed region heat islands during the rapid urbanization (1995-2015) of Southern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 674, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, S.; Shi, W.; Zhu, X.; Abbas, S. Monitoring of land use/land cover and socioeconomic changes in south China over the last three decades using Landsat and Nighttime Light data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Bao, W. The characteristics of rain in the raining seasons in Guangdong province and its relationship with sea surface temperature (SST). In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical and Control Engineering, Yichang, China, 16–18 September 2011; pp. 3216–3219. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, X.; Chen, X. Trend analysis of hydrological and meteorological factors in Guangdong under climate change. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Water Resource and Environmental Protection, Xi’an, China, 20–22 May 2011; pp. 584–587. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhu, L.; Yang, G.; Li, D. Anthropogenic mercury enrichment factors and contributions in soils of Guangdong Province, south China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2014, 114, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, D.; Zhuo, M.; Guo, T.; Liao, Y.; Xie, Z. Effects of rainfall intensity and slope gradient on erosion characteristics of the red soil slope. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2015, 29, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, Q.; Ma, L.J.; Ding, S.Y.; Xu, S.; Wu, C.; Liu, P. Spatiotemporal variations in rainfall erosivity during the period of 1960-2011 in Guangdong Province, southern China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 128, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levia, D.F.; Frost, E.E. Variability of throughfall volume and solute inputs in wooded ecosystems. Prog. Phys. Geog. 2006, 30, 605–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.K.; Li, J. A modified Gash Model for estimating rainfall interception loss of forest using remote sensing observations at regional scale. Water 2014, 6, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.X.; Wang, Y.J.; Ma, C.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zhang, H.L.; Hu, B. Quantifying the effect of non-spatial and spatial forest stand structure on rainfall partitioning in mountain forests, Southern China. Forest. Chron. 2018, 94, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Wang, C.Z.; Li, X.X.; Zhang, H.W.; Li, W.L.; Jiang, L.Q. Impacts of agricultural expansion (1910s-2010s) on the water cycle in the Songneng plain, Northeast China. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.Y.; Wei, X.H.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, M.F.; Li, Y.L.; Qiao, Y.N.; Liu, H.G.; Wang, C.L. Forest recovery and river discharge at the regional scale of Guangdong province, China. Water Resour. Res. 2010, 46, W09503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Z.; Liu, X.D.; Zhou, G.Y.; Han, L.S.; Liu, W.; Liao, J.S. 50-year evapotranspiration declining and potential causations in subtropical Guangdong province, southern China. Catena 2015, 128, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Hou, C.M.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.M.; Ren, H.; Ye, W.H. The value of forest ecosystem services of Guangdong province. Ecol. Sci. 2002, 21, 160–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Su, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Sun, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yang, J.; et al. Redistribution characteristics of atmospheric precipitation in different spatial levels of Guangzhou urban typical forests in southern China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2019, 10, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MODIS terrestrial standard product MOD13A1. Available online: http://www.gscloud.cn (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- De Roo, A.P.J.; Wesseling, C.G. LISEM: A single-event physically based hydrological and soil erosion model for drainage basins. I: Theory, input and output. Hydrol. Process. 1996, 10, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aston, A.R. Rainfall interception by eight small trees. J. Hydrol. 1979, 42, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, R.A. A note on the interception loss equation. J. Geophys. Res. 1960, 65, 3850–3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.X.; Chen, X.Z.; Li, Y.; Liao, J.S.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, N.; Kuang, Y. China’s 19-year city-level carbon emissions of energy consumptions, driving forces and regionalized mitigation guidelines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 35, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattan, P.; Bussiere, F.; Nouvellon, A. Evidence of large rainfall partitioning patterns by banana and impact on surface runoff generation. Hydrol. Process. 2007, 21, 2196–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.L.; Formiga, K.T.M.; Traldi, M.A.B. Rainfall interception capacity of tree species used in urban afforestation. Urban Ecosyst. 2018, 21, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathizadeh, O.; Attarod, P.; Pypker, T.G.; Darvishsefat, A.A.; Amiri, G.Z. Seasonal variability of rainfall interception and canopy storage capacity measured under individual Oak (Quercus brantii) trees in western Iran. J. Agr. Sci. Tech. 2013, 15, 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.K.; Yu, B.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Che, S.Q. Predicted models for potential canopy rainfall interception capacity of landscape trees in Shanghai, China. Eur. J. For. Res. 2017, 136, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.L.; Yang, S.T.; Lu, J.X.; Liu, C.M.; Wang, S.D. Simulation and analysis of vegetation interception at a large scale in the middle reaches of Yellow River. Acta Geographica Sinica 2014, 69, 80–89, in Chinese with English abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.H.; Shi, Z.J.; Wang, Y.H.; Xiong, W.; Yu, P.T. Canopy interception characteristics of main vegetation types in Liupan Mountains of China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 21, 2487–2493. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.J.; Zhou, G.Y.; Wu, Z.M.; Zhou, B.; Luo, X.H. Characteristics of the canopy interception in an evergreen broad-leaved secondary forest in Yangdongshan, North Guangdong. Scientia Silvae Sinicae 2011, 47, 157–161, in Chinese with English abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Pypker, T.G.; Levia, D.F.; Staelens, J.; Van Stan, I.I.J.T. Canopy structure in relation to hydrological and biogeochemical fluxes. In Forest Hydrology and Biogeochemistry; Levia, D., Carlyle-Moses, D., Tanaka, T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 216, pp. 371–388. [Google Scholar]

- Levia, D.; Michalzik, B.; Näthe, K.; Bischoff, S.; Richter, S.; Legates, D. Differential stemflow yield from European beech saplings: The role of individual canopy structure metrics. Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, P.; Domingo, F.; Garcia-Estringana, P.; Muzylo, A.; Gallart, F. Canopy wetness patterns in a Mediterranean deciduous stan. J. Hydrol. 2014, 512, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Parra, J.; Schnable, S.; Ceballo-Barbancho, C. The role of vegetation covers on soil wetting processes at rainfall event scale in scattered tree woodland of Mediterranean climate. J. Hydrol. 2015, 529, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, S.Y.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Zheng, X.R.; Hu, X.; Huang, Y.M. Stemflow and its controlling factors in the subshrub Artemisia ordosica during two contrasting growth stages in the Mu Us sandy land of northern China. Hydrol. Res. 2016, 47, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, C.D.; Gibbes, C. Influence of leaf and canopy characteristics on rainfall interception and urban hydrology. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2017, 62, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nytch, C.J.; Melendez-Ackerman, E.J.; Perez, M.; Ortiz-Zayas, J.R. Rainfall interception by six urban trees in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Urban Ecosyst. 2009, 22, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, D.G.; Gash, J.H.; Holmes, T.R.H.; de Jeu, R.A.M.; Dolman, A.J. Global canopy interception from satellite observations. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, D16122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staelens, J.; De Schrijver, A.; Verheyen, K.; Verhoest, N.E.C. Rainfall partitioning into throughfall, stemflow, and interception within a single beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) canopy: Influence of foliation, rain event characteristics, and meteorology. Hydrol. Process. 2008, 22, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; McPherson, E.G. Surface water storage capacity of twenty tree species in Davis, California. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categorization | High Interception Area | Moderate Interception Area | Low Interception Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canopy rainfall interception (mm) | ≥ 90 | 60 ≤ < 90 | < 60 |

| Year | High Interception Area | Moderate Interception Area | Low Interception Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 94.51 | 71.22 | 45.48 |

| 2008 | 90.88 | 72.92 | 52.68 |

| 2012 | 101.22 | 82.66 | 59.61 |

| 2016 | 131.83 | 107.23 | 70.26 |

| Climatic Zone | Middle Subtropical Zone | Northern South Subtropical Zone | Southern South Subtropical Zone | North Tropical Zone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basin | YYH | WJ | PJ | HGH | NJ | LJ | YLH | DSH |

| Forest area (ha) | 11,692.88 | 260,878.3 | 104,807.6 | 97,092.87 | 321,499.5 | 155,122.1 | 15,207.23 | 18,906.87 |

| Coverage (%) | 72.62 | 73.92 | 70.82 | 69.34 | 71.62 | 73.80 | 67.26 | 68.05 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Sun, C.; Su, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Liao, J.; He, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; et al. Estimating Rainfall Interception of Vegetation Canopy from MODIS Imageries in Southern China. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212468

Wu J, Liu L, Sun C, Su Y, Wang C, Yang J, Liao J, He X, Li Q, Zhang C, et al. Estimating Rainfall Interception of Vegetation Canopy from MODIS Imageries in Southern China. Remote Sensing. 2019; 11(21):2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212468

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jianping, Liyang Liu, Caihong Sun, Yongxian Su, Changjian Wang, Ji Yang, Jiayuan Liao, Xiaolei He, Qian Li, Chaoqun Zhang, and et al. 2019. "Estimating Rainfall Interception of Vegetation Canopy from MODIS Imageries in Southern China" Remote Sensing 11, no. 21: 2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212468

APA StyleWu, J., Liu, L., Sun, C., Su, Y., Wang, C., Yang, J., Liao, J., He, X., Li, Q., Zhang, C., & Zhang, H. (2019). Estimating Rainfall Interception of Vegetation Canopy from MODIS Imageries in Southern China. Remote Sensing, 11(21), 2468. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11212468