One-Carbon Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Brain Tissue

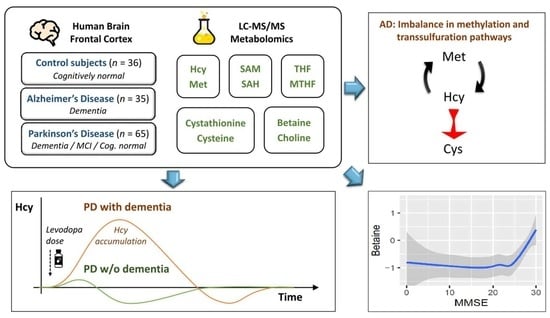

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects

2.2. Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

2.3. Data Preprocessing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Subject Characteristics

3.2. Differential Analysis

3.3. Levodopa Interaction

3.4. MMSE Associations

3.5. Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. One-Carbon Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia

4.2. One-Carbon Metabolism in Parkinson’s Disease with Dementia

4.3. One-Carbon Metabolism in Parkinson’s Disease without Dementia

4.4. The Role of Betaine and Hydrogen Sulfide

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perła-Kaján, J.; Twardowski, T.; Jakubowski, H. Mechanisms of homocysteine toxicity in humans. Amino Acids 2007, 32, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieminska, E.; Lazarewicz, J.W. Excitotoxic neuronal injury in chronic homocysteine neurotoxicity studied in vitro: The role of NMDA and group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. Wars 2006, 66, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cacciari, E.; Salardi, S. Clinical and laboratory features of homocystinuria. Haemostasis 1989, 19 (Suppl. 1), 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, I.M.; Daly, L.E.; Refsum, H.M.; Robinson, K.; Brattström, L.E.; Ueland, P.M.; Palma-Reis, R.J.; Boers, G.H.; Sheahan, R.G.; Israelsson, B.; et al. Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease. The European Concerted Action Project. JAMA 1997, 277, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virtanen, J.K.; Voutilainen, S.; Happonen, P.; Alfthan, G.; Kaikkonen, J.; Mursu, J.; Rissanen, T.H.; Kaplan, G.A.; Korhonen, M.J.; Sivenius, J.; et al. Serum homocysteine, folate and risk of stroke: Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor (KIHD) Study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2005, 12, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tie, T.; Cheng, Y.; Su, X.; Man, Z.; Hou, J.; Sun, L.; Tian, M.; et al. The association between homocysteine and ischemic stroke subtypes in Chinese: A meta-analysis: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2020, 99, e19467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, S.; Beiser, A.; Selhub, J.; Jacques, P.F.; Rosenberg, I.H.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Wilson, P.W.F.; Wolf, P.A. Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzlerová, E.; Fisar, Z.; Jirák, R.; Zvĕrová, M.; Hroudová, J.; Benaková, H.; Raboch, J. Plasma homocysteine in Alzheimer’s disease with or without co-morbid depressive symptoms. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2014, 35, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Aarsland, D.; Andersen, K.; Larsen, J.P.; Lolk, A.; Nielsen, H.; Kragh-Sørensen, P. Risk of dementia in Parkinson’s disease: A community-based, prospective study. Neurology 2001, 56, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Tiandong, W.; Yang, L.; Huaxing, M.; Guowen, M.; Yalan, F.; Xiaoyuan, N. Parkinson’s disease and homocysteine: A community-based study in a folate and vitamin B12 deficient population. Parkinsons Dis. 2016, 2016, 9539836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, S.M.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Logroscino, G.; Willett, W.C.; Ascherio, A. Folate intake and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 160, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- de Lau, L.M.L.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Witteman, J.C.M.; Hofman, A.; Breteler, M.M.B. Dietary folate, vitamin B12, and vitamin B6 and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology 2006, 67, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Suilleabhain, P.E.; Bottiglieri, T.; Dewey, R.B., Jr.; Sharma, S.; Diaz-Arrastia, R. Modest increase in plasma homocysteine follows levodopa initiation in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2004, 19, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; van Hilten, J.J.; Marinus, J. Predictors of dementia in Parkinson’s disease; findings from a 5-year prospective study using the SCOPA-COG. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2014, 20, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christine, C.W.; Auinger, P.; Joslin, A.; Yelpaala, Y.; Green, R. Parkinson Study Group-DATATOP Investigators Vitamin B12 and homocysteine levels predict different outcomes in early Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suszynska, J.; Tisonczyk, J.; Lee, H.-G.; Smith, M.A.; Jakubowski, H. Reduced homocysteine-thiolactonase activity in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010, 19, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, B.P.; Bottiglieri, T.; Arning, E.; Ziegler, M.G.; Hansen, L.A.; Masliah, E. Elevated S-adenosylhomocysteine in Alzheimer brain: Influence on methyltransferases and cognitive function. J. Neural Transm. 2004, 111, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, T.G.; Adler, C.H.; Sue, L.I.; Serrano, G.; Shill, H.A.; Walker, D.G.; Lue, L.; Roher, A.E.; Dugger, B.N.; Maarouf, C.; et al. Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders and brain and Body Donation Program: Arizona brain and body donation program. Neuropathology 2015, 35, 354–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Institute on Aging and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 1997, 18, S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandania, J.; Kokkonen, M.; Euro, L.; Velagapudi, V. Simultaneous measurement of folate cycle intermediates in different biological matrices using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2018, 1092, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garg, U. (Ed.) Clinical Applications of Mass Spectrometry in Biomolecular Analysis: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781493950096. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781544336473. [Google Scholar]

- Tukey, J.W. Exploratory Data Analysis; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1977; ISBN 9780201076165. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, J.; Bates, D.; DebRoy, S.; Sarkar, D. R Core Team. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. In The Comprehensive R Archive Network; R Package Version 3.1-152. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Huang, Y.; Qiu, M.; Yin, C.; Ren, H.; Gan, H.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, J.; Li, W.; et al. Immunoassay of S-adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocysteine: The methylation index as a biomarker for disease and health status. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mirra, S.S.; Heyman, A.; McKeel, D.; Sumi, S.M.; Crain, B.J.; Brownlee, L.M.; Vogel, F.S.; Hughes, J.P.; van Belle, G.; Berg, L. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1991, 41, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beach, T.G.; Adler, C.H.; Lue, L.; Sue, L.I.; Bachalakuri, J.; Henry-Watson, J.; Sasse, J.; Boyer, S.; Shirohi, S.; Brooks, R.; et al. Unified staging system for Lewy body disorders: Correlation with nigrostriatal degeneration, cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 117, 613–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pey, A.L.; Majtan, T.; Sanchez-Ruiz, J.M.; Kraus, J.P. Human cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) contains two classes of binding sites for S-adenosylmethionine (SAM): Complex regulation of CBS activity and stability by SAM. Biochem. J. 2013, 449, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miller, J.W.; Green, R.; Mungas, D.M.; Reed, B.R.; Jagust, W.J. Homocysteine, vitamin B6, and vascular disease in AD patients. Neurology 2002, 58, 1471–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, K.; Lao, J.I.; Carrato, C.; Rodriguez-Vila, A.; Latorre, P.; Mataró, M.; Llopis, M.A.; Mate, J.L.; Ariza, A. Cystathionine beta synthase as a risk factor for Alzheimer disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2004, 1, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eto, K.; Asada, T.; Arima, K.; Makifuchi, T.; Kimura, H. Brain hydrogen sulfide is severely decreased in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 293, 1485–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.M.; Johnson, D.K.; Watts, A.; Swerdlow, R.H.; Brooks, W.M. Reduced lean mass in early Alzheimer disease and its association with brain atrophy. Arch. Neurol. 2010, 67, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douaud, G.; Refsum, H.; de Jager, C.A.; Jacoby, R.; Nichols, T.E.; Smith, S.M.; Smith, A.D. Preventing Alzheimer’s disease-related gray matter atrophy by B-vitamin treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9523–9528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sun, J.; Wen, S.; Zhou, J.; Ding, S. Association between malnutrition and hyperhomocysteine in Alzheimer’s disease patients and diet intervention of betaine. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2017, 31, e22090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsui, J.K.; Ross, S.; Poulin, K.; Douglas, J.; Postnikoff, D.; Calne, S.; Woodward, W.; Calne, D.B. The effect of dietary protein on the efficacy of L-dopa: A double-blind study. Neurology 1989, 39, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, R.G.; Daubner, S.C. Modulation of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase activity by S-adenosylmethionine and by dihydrofolate and its polyglutamate analogues. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 1982, 20, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finkelstein, J.D.; Martin, J.J. Inactivation of betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase by adenosylmethionine and adenosylethionine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984, 118, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Miyake, Y.; Sasaki, S.; Tanaka, K.; Fukushima, W.; Kiyohara, C.; Tsuboi, Y.; Yamada, T.; Oeda, T.; Miki, T.; et al. Dietary intake of folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12 and riboflavin and risk of Parkinson’s disease: A case-control study in Japan. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rojo-Sebastián, A.; González-Robles, C.; García de Yébenes, J. Vitamin B6 deficiency in patients with Parkinson disease treated with levodopa/carbidopa. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 43, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.W.; Selhub, J.; Nadeau, M.R.; Thomas, C.A.; Feldman, R.G.; Wolf, P.A. Effect of L-dopa on plasma homocysteine in PD patients: Relationship to B-vitamin status. Neurology 2003, 60, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, L.; Watkins, C.J.; Wiggins, J.F.; Wurtman, R.J. Effect of pyridoxine on the depletion of tissue pyridoxal phosphate by carbidopa. Metabolism 1978, 27, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnolo, A.; Merola, A.; Artusi, C.A.; Rizzone, M.G.; Zibetti, M.; Lopiano, L. Levodopa-induced neuropathy: A systematic review: Levodopa-induced neuropathy. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2019, 6, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van der Steen, W.; den Heijer, T.; Groen, J. Vitamin B6 deficiency caused by the use of levodopa. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2018, 162, D2818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; He, F.; Wu, C.; Li, P.; Li, N.; Deng, J.; Zhu, G.; Ren, W.; Peng, Y. Betaine in inflammation: Mechanistic aspects and applications. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Veskovic, M.; Mladenovic, D.; Milenkovic, M.; Tosic, J.; Borozan, S.; Gopcevic, K.; Labudovic-Borovic, M.; Dragutinovic, V.; Vucevic, D.; Jorgacevic, B.; et al. Betaine modulates oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, autophagy, and Akt/mTOR signaling in methionine-choline deficiency-induced fatty liver disease. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 848, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alirezaei, M. Betaine protects cerebellum from oxidative stress following levodopa and benserazide administration in rats. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2015, 18, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tabassum, R.; Jeong, N.Y.; Jung, J. Protective effect of hydrogen sulfide on oxidative stress-induced neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandiver, M.S.; Paul, B.D.; Xu, R.; Karuppagounder, S.; Rao, F.; Snowman, A.M.; Ko, H.S.; Lee, Y.I.; Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M.; et al. Sulfhydration mediates neuroprotective actions of parkin. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tabassum, R.; Jeong, N.Y. Potential for therapeutic use of hydrogen sulfide in oxidative stress-induced neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 16, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Controls (n = 36) | AD-Dem (n = 35) | PD-Dem (n = 32) | PD-MCI (n = 19) | PD-CN (n = 14) | p1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male, no. (%) | 22 (61%) | 20 (57%) | 24 (75%) | 14 (74%) | 8 (57%) | 0.47 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 82 (10) | 81 (9) | 80 (5) | 82 (6) | 85 (6) | 0.1 |

| Race | All White Americans | 1 | ||||

| APOE, ε4 carrier, no. (%) | 5 (14%) | 18 (51%) | 3 (9%) | 3 (16%) | 2 (14%) | <0.001 |

| BMI 2, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 25 (5) | 24 (4) | 27 (9) | 25 (8) | 22 (4) | 0.08 |

| MMSE 2,3, points, mean (SD) | 28 (1) | 15 (8) | 20 (6) | 25 (3) | 28 (1) | <0.001 |

| UPDRS-M 2,4, points, mean (SD) | 7 (5) | 17 (18) | 50 (16) | 31 (15) | 32 (15) | <0.001 |

| Diagnosis duration, years, mean (SD) | N/A | 9 (4) | 18 (9) | 12 (6) | 11 (7) | <0.001 |

| Neurofibrillary tangles, density score, mean (SD) | 3 (2) | 14 (2) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 5 (3) | <0.001 |

| Senile plaque, density score, mean (SD) | 3 (4) | 14 (1) | 2 (3) | 5 (6) | 5 (5) | <0.001 |

| Unified Lewy body stage, score, mean (SD) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3.4 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Vitamin B12 2, supplementing, no. (%) | 3 (8%) | 2 (6%) | 5 (16%) | 2 (11%) | 2 (14%) | 0.67 |

| Multivitamin 2, supplementing, no. (%) | 17 (47%) | 8 (23%) | 10 (31%) | 6 (32%) | 9 (64%) | 0.047 |

| Post-mortem interval, hours, mean (SD) | 3.2 (1.0) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.4 (1.2) | 3.3 (0.9) | 0.87 |

| Freezer storage, years, mean (SD) | 11 (4) | 8 (2) | 9 (4) | 7 (4) | 9 (4) | <0.001 |

| Controls | AD | PD-Dem | PD-MCI | PD-CN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THF, pmol/g, mean (SD) | 144 (78) | 104 (50) | 106 (63) | 118 (64) | 128 (36) |

| MTHF, pmol/g, mean (SD) | 199 (106) | 217 (108) | 188 (110) | 217 (110) | 201 (93) |

| SAM, nmol/g, mean (SD) | 12.7 (5.0) | 15.4 (4.7) | 13.1 (4.6) | 13.0 (5.6) | 14.1 (5.7) |

| SAH, nmol/g, mean (SD) | 13.6 (3.2) | 14.4 (3.0) | 15.5 (3.0) | 14.3 (3.0) | 13.5 (2.7) |

| Met, nmol/g, mean (SD) | 80.7 (36.7) | 105 (56.8) | 80.6 (28.0) | 96.3 (69.5) | 77.6 (40.2) |

| CTH, nmol/g, mean (SD) | 608 (571) | 578 (424) | 779 (812) | 538 (466) | 499 (435) |

| Bet, nmol/g, mean (SD) | 49.1 (31.8) | 27.5 (18.3) | 27.9 (25.4) | 28.4 (18.3) | 52.0 (29.4) |

| Cho, nmol/g, mean (SD) | 213 (168) | 116 (61) | 139 (75) | 144 (67) | 179 (72) |

| Hcy, nmol/g, mean (SD) | 109 (83) | 171 (130) | 157 (140) | 123 (97) | 93 (63) |

| Cys, nmol/g, mean (SD) | 2981 (1214) | 4596 (2260) | 3787 (1553) | 3255 (1163) | 3192 (1203) |

| DOPA, pmol/g, mean (SD) | 38 (25) | 59 (124) | 744 (3337) | 238 (603) | 659 (1257) |

| AD-Dem | PD-Dem | PD-MCI | PD-CN | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p 1 | FDR | β | 95% CI | p 1 | FDR | β | 95% CI | p 1 | FDR | β | 95% CI | p 1 | FDR | |

| THF | −48% | (−93; −3%) | 0.040 | 0.09 | −49% | (−98; 0%) | 0.051 | 0.13 | −32% | (−91; 26%) | 0.28 | 0.84 | −13% | (−58; 31%) | 0.56 | 0.95 |

| MTHF | −14% | (−65; 38%) | 0.61 | 0.68 | −28% | (−80; 25%) | 0.30 | 0.43 | −3% | (−62; 56%) | 0.92 | 0.92 | −4% | (−60; 52%) | 0.88 | 0.95 |

| SAM | 48% | (1; 95%) | 0.046 | 0.09 | 8% | (−37; 53%) | 0.73 | 0.73 | −3% | (−61; 55%) | 0.92 | 0.92 | 38% | (−29; 105%) | 0.27 | 0.95 |

| SAH | 20% | (−28; 69%) | 0.42 | 0.52 | 55% | (9; 101%) | 0.020 | 0.10 | 23% | (−34; 80%) | 0.43 | 0.84 | 11% | (−46; 68%) | 0.70 | 0.95 |

| Met | 35% | (−20; 90%) | 0.22 | 0.31 | −11% | (−57; 36%) | 0.65 | 0.72 | 7% | (−52; 66%) | 0.82 | 0.92 | −15% | (−88; 59%) | 0.70 | 0.95 |

| CTH | 7% | (−40; 54%) | 0.77 | 0.77 | 16% | (−36; 69%) | 0.54 | 0.68 | −16% | (−73; 41%) | 0.59 | 0.84 | −10% | (−72; 53%) | 0.76 | 0.95 |

| Bet | −86% | (−137; −35%) | 0.001 | 0.007 | −82% | (−136; −28%) | 0.004 | 0.035 | −69% | (−132; −7%) | 0.032 | 0.32 | 11% | (−48; 69%) | 0.72 | 0.95 |

| Cho | −51% | (−96; −6%) | 0.028 | 0.09 | −39% | (−85; 7%) | 0.10 | 0.19 | −22% | (−68; 24%) | 0.36 | 0.84 | −1% | (−51; 48%) | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| Hcy | 44% | (−8; 96%) | 0.10 | 0.17 | 34% | (−15; 83%) | 0.17 | 0.29 | 17% | (−37; 71%) | 0.54 | 0.84 | −9% | (−73; 55%) | 0.79 | 0.95 |

| Cys | 114% | (54; 173%) | <0.001 | 0.003 | 55% | (1; 109%) | 0.050 | 0.13 | 25% | (−32; 81%) | 0.39 | 0.84 | 23% | (−40; 86%) | 0.48 | 0.95 |

| MMSE (All Subjects) | MMSE (PD Subjects) | MMSE (PD Subjects, DOPA Interaction) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p 1 | FDR | β | 95% CI | p 1 | FDR | β | 95% CI | p 1 | FDR | |

| THF | 3% | (1; 5%) | 0.010 | 0.034 | 2% | (−2; 7%) | 0.30 | 0.50 | 1% | (−4; 5%) | 0.82 | 0.98 |

| MTHF | 2% | (0; 5%) | 0.10 | 0.14 | 1% | (−4; 6%) | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0% | (−5; 5%) | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| SAM | −3% | (−5; −1%) | 0.014 | 0.035 | −4% | (−8; 1%) | 0.10 | 0.33 | −4% | (−9; 0%) | 0.09 | 0.29 |

| SAH | −2% | (−4; 1%) | 0.17 | 0.19 | −2% | (−6; 3%) | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0% | (−4; 4%) | 0.88 | 0.98 |

| Met | −1% | (−3; 2%) | 0.64 | 0.64 | 2% | (−3; 6%) | 0.44 | 0.54 | 1% | (−4; 6%) | 0.58 | 0.98 |

| CTH | −2% | (−4; 0%) | 0.08 | 0.13 | −4% | (−9; 2%) | 0.17 | 0.43 | −1% | (−6; 4%) | 0.76 | 0.98 |

| Bet | 4% | (1; 7%) | 0.005 | 0.026 | 8% | (3; 14%) | 0.002 | 0.021 | 8% | (3; 13%) | 0.002 | 0.019 |

| Cho | 2% | (−1; 4%) | 0.16 | 0.20 | 5% | (1; 9%) | 0.027 | 0.13 | 4% | (0; 8%) | 0.08 | 0.29 |

| Hcy | −3% | (−6; −1%) | 0.018 | 0.035 | −3% | (−8; 2%) | 0.27 | 0.50 | 1% | (−4; 5%) | 0.80 | 0.98 |

| Cys | −5% | (−8; −2%) | <0.001 | 0.009 | −2% | (−8; 3%) | 0.39 | 0.54 | −2% | (−7; 3%) | 0.48 | 0.98 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalecký, K.; Ashcraft, P.; Bottiglieri, T. One-Carbon Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Brain Tissue. Nutrients 2022, 14, 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030599

Kalecký K, Ashcraft P, Bottiglieri T. One-Carbon Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Brain Tissue. Nutrients. 2022; 14(3):599. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030599

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalecký, Karel, Paula Ashcraft, and Teodoro Bottiglieri. 2022. "One-Carbon Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Brain Tissue" Nutrients 14, no. 3: 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030599

APA StyleKalecký, K., Ashcraft, P., & Bottiglieri, T. (2022). One-Carbon Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Brain Tissue. Nutrients, 14(3), 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030599