Iodine and Mental Development of Children 5 Years Old and Under: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment of RCT

3. Results

3.1. Trial Flow

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Mental Development Tests Used

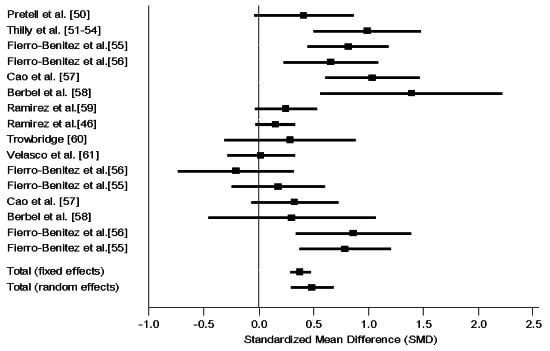

3.4. Associations between Iodine and Mental Development

| Author, country | Design, treatment population and doses | Sample size | Age at testing | Biological indicator | Mental development test | Outcomes | Group comparisons (mean ± SD) | Effect size d (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT | ||||||||

| Pretell et al., Peru [50] | Double blind RCT | n = 72 | 0–5 years | UIE, T4, T3, TSH, TI, TBG | Brunet-Lézine | 0 | G1 (80.0 ± 12) > Gc (75.0 ± 12) | 0.41 (−0.04, 0.86) |

| Iodized oil group (G1) vs. placebo (Gc) | G1 (n = 35) | Enrollment [51] | Stanford-Binet | Estimated from graph | ||||

| W, PW in early pregnancy | Gc (n = 46) | UIE = 17 μg/24 h | ||||||

| Single dose of 95–950 mg Iodine | T4 = 4.1 μg/100 mL | |||||||

| Severe ID area (Goiter 83%) | ||||||||

| Thilly et al., DR Congo [52,53,54,55] | Double blind RCT | n = 75 | 4–23 months | UIE, T4, fT4, T3, TSH, TBG | Brunet-Lézine | + | G1 (115 ± 3) > Gc (103 ± 4) ** | 0.99 (0.50, 1.48) |

| Iodized oil group (G1) vs. placebo (Gc) | G1 (n = 39) | Enrollment | ||||||

| PW in 2st and 3nd trimester | Gc (n = 36) | T4 = 11.3 μg/dL | ||||||

| Single dose of 475 mg Iodine | T3 = 206 ng/dL | |||||||

| Severe ID area (Goiter 62%) | TSH = 8.2 μU/mL | |||||||

| Non-RCT | ||||||||

| Berbel et al., Spain [56] | Comparative post only | n = 44 | 18 months | UIE, fT4, TSH | Brunet-Lézine | + | G1 (101.8 ± 9.7) > G2 (92.2 ± 15.4) * | 1.38 (0.45, 2.32) |

| Treatment groups, PW? | G1 (n = 13) | Enrollment | Gross motor | + | G1 (101.8 ± 9.7) > Gc (87.5 ± 8.9) *** | 1.39 (0.57, 2.22) | ||

| Daily dose of 200 μg KI from enrollment (G1: 1st trimester, G2: 2nd trimester, Gc: after delivery) to end of lactation | G2 (n = 12) | G1 (TSH < 4.8 μU/mL; fT4 > 0.91 ng/dL) | Fine motor | + | G2 (92.2 ± 15.4) = Gc (87.5 ± 8.9) | 0.31 (−0.45, 1.06) | ||

| Mild ID area | Gc (n = 19) | G2 and Gc (TSH < 4.8 μU/mL; fT4 = 0.91 to 0.82 ng/dL) | Language | 0 | ||||

| Socialization | + | |||||||

| Cao et al., China [57] | Comparative pre-post | n = 404 | 2 years? | UIE, T4, TSH? | Bayley-I | + | G1 (77 ± 11) = Gc (75 ± 18) | 1.04 (0.61, 1.47) |

| Iodized oil group vs. historical control | G1 (n = 28) | Enrollement | G2 (90 ± 14) > Gc( 75 ± 18) *** | 0.33 (−0.06, 0.72) | ||||

| PW and Infant? | G2 (n = 71) | UIE = 10 to 25 μg/L | G3 (80 ± 15) = Gc (75 ± 18) | 0.33 (−0.03, 0.69) | ||||

| Single dose of 400 mg iodine (PW: G1 1st trim; G2 2nd trim; G3 3rd trim); 200 mg (children > 12 months) and 50 mg (Infant: G4 0–3 months, G5 3–12 months) vs. historical control (Gc) | G3 (n = 85) | G4, G5 (80 ± 10) = Gc (75 ± 18) | ||||||

| Severe ID area (Goiter 54%) | G4 (n = 90) | G1 received 0.4 mg Iodine instead of 400 mg due to government new supplementation program | ||||||

| G5 (n = 93) | ||||||||

| Gc (n = 37)? | ||||||||

| Fierro-Benitez et al., Ecuador [58] | Comparative post only? | n = 150 | 41–60 months | Enrollment [59] | Stanford-Binet | + | G1 (80.1) > Gc1 (70.1) *? | 0.66 (0.23, 1.09) |

| Treatment cluster vs. control cluster (Gc) | G1 (n = 41) | UIE: 0.37 μg/100 mL (Treatment cluster); 0.63 μg/100 mL (Control cluster) | G2 (67.0) = Gc2 (70.1) | −0.20 (−0.73, 0.32) | ||||

| W, PW and children | Gc1(n = 50) | G1 (80.1) > G2 (67.0) * | 0.86 (0.34, 1.39) | |||||

| Several doses: 95 mg Iodine (<2 years), 238 mg (2–6 years), 475 mg (6–12 years) and 950 mg (>12 years) | G2 (n = 26) | |||||||

| G1: children supplemented in early intrauterine life, in lactation and by injection; G2: children supplemented in last period (7–9th month) of fetal life, in lactation and by injection | Gc2 (n = 33) | |||||||

| Severe ID area (Goiter 53%–70%) [59] | ||||||||

| Fierro-Benitez et al., Ecuador [60] | Comparative post only? | n = 216 | 3–5 years | Enrollment [59] | Stanford-Binet | + | G1 (83.66 ± 13.4) > Gc1 (72.74 ± 14.0) **? | 0.81 (0.45, 1.19) |

| Treatment cluster vs. control cluster (Gc) | G1 (n = 63) | UIE: 0.37 μg/100 mL (Treatment cluster); 0.63 μg/100 mL (Control cluster) | G2 (71.72 ± 14.6) = Gc2 (69.16 ± 13.3) | 0.18 (−0.24, 0.60) | ||||

| W and PW | Gc1(n = 63) | G1 (83.66 ± 13.4) vs. G2 (71.72 ± 14.6) | 0.79 (0.37, 1.21) | |||||

| Several doses: 95 mg Iodine (<2 years), 238 mg (2–6 years), 475 mg (6–12 years) and 950 mg (>12 years) | G2 (n = 40) | |||||||

| G1: Supplementation prior to conception, in lactation and by injection; G2: Supplementation in 4–7th month of fetal life, in lactation and by injection | Gc2 (n = 50) | |||||||

| Severe ID area (Goiter 53%–70%) [59] | ||||||||

| Ramirez et al., Ecuador [61] | Comparative post only | n = 227 | 9, 13 and 18 months | UIE, T4, TI, PBI, BEI, BII [59] | Gesell | 0 | G1 (92.77) = Gc (89) [62] | 0.25 (−0.03, 0.53) |

| Treatment cluster (G1) vs. control cluster (Gc) | G1 (n = 72) | Enrollment [59] | ||||||

| PW | Gc (n = 155) | UIE: 0.37 μg/100 mL (Treatment cluster); 0.63 μg/100 mL (Control cluster) | ||||||

| Single dose of 950 mg Iodine [59] | ||||||||

| Severe ID area (Goiter 53%–70%) [59] | ||||||||

| Ramirez et al., Ecuador [46] | Comparative post only | n = 583 | 3–60 months | Enrollment [59] | Gesell | 0 | G1 (89.7) vs. Gc (87.4) (Estimated) | 0.15 (−0.02, 0.33) |

| Treatment cluster (G1) vs. control cluster (Gc) | G1 (n = 183) | UIE: 0.37 μg/100 mL (Treatment cluster); 0.63 μg/100 mL (Control cluster) | ||||||

| W and PW (0th–5th month) | Gc (n = 400) | |||||||

| Single dose of 950 mg Iodine | ||||||||

| Severe ID area (Goiter 53%–70%) [59] | ||||||||

| Trowbridge, Ecuador [63] | Comparative post only | n = 125 | 3–5 years | Enrollment [59] | Stanford-Binet | 0 | G1 (76.8) = Gc1 (72.4) | 0.29 (−0.31, 0.89) |

| Treatment cluster vs. control cluster (Gc) | G1 (n = 22) | UIE: 0.37 μg/100 mL (Treatment cluster); 0.63 μg/100 mL (Control cluster) | G2 (72.3) = Gc2 (69.0) | 0.22 (−0.40, 0.83) | ||||

| W, PW, and Infant? | Gc1 (n = 24) | G3 (65.2) = Gc3 (69.9) | −0.31 (−1.00, 0.39) | |||||

| Single dose of 950 mg Iodine [64] (G1 prior to conception; G2 during pregnancy), 95 mg Iodine (G3 between 0 and 9 months of age) | G2 (n = 21) | G1 (76.8) > G3 (65.2) ** | ||||||

| Severe ID area (Goiter 53%–70%) [59] | Gc2 (n = 23) | |||||||

| G3 (n = 16) | ||||||||

| Gc3 (n = 19) | ||||||||

| Velasco et al., Spain [65] | Comparative post only | n = 194 | 3–18 months | UIE, fT4, fT3, TSH, Tg | Bayley-I | 0 | G1 (109.22 ± 11.73) = Gc (108.9 ± 13.41) | 0.02 (−0.28, 0.33) |

| Treatment group (G1) vs. control group (Gc) | G1 (n = 133) | Enrollment | ||||||

| PW, postpartum W | Gc (n = 61) | G1: 153–213 μg/L (UIE); 8.8–10.6 pmol/L (fT4) | ||||||

| Daily dose of 300 μg iodine (KI) from 1st trimester through lactation | Gc: 87.6 (UIE); 9.0 pmol/L (fT4) | |||||||

| Moderate ID area | ||||||||

| Author, country | Design, groups | Sample size | Age at testing | Biological indicator | Mental development test | Outcomes | Group comparisons (mean ± SD) | Effect size d (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costeira et al., Portugal [66] | Cohort Prospective | n = 86 | 12, 18 and 24 months | UIE, tT4, fT4, tT3, fT3, TSH, at 1st, 2nd and 3rd trimester | Bayley-I 12 months | + | G1 (77.7 ± 17.9) < Gc (99.3 ± 17.6) * | 1.18 (0.37, 1.99) |

| G1 (hypothyroid: fT3 < 10th percentile) at 3rd trimester | G1 (n = 9) | Bayley-I 24 months | 0 | G1 (91.1 ± 21.4) = Gc (100.7 ± 17.2) | 0.52 (−0.25, 1.29) | |||

| Gc (euthyroid: fT3 between 50th and 90th percentile) at 3rd trimester | Gc (n = 33) | |||||||

| Moderate ID area | ||||||||

| Galan et al., Spain [47] | Cohort Prospective | n = 61 | 37–47 months (Mean = 40) | UIE, fT4, TSH, TPOAb at 1st and 3rd trimester | McCarthy | + | G1 (97.7) < Gc (105.5) * | 0.64 (0.12, 1.17) |

| G1 (UIE < 200 μg/L at 12 weeks) | G1 (n = 30) | Verbal | + | G1 (49.4) < Gc (55.2) * | ||||

| Gc (UIE ≥ 200 μg/L at 12 weeks) | Gc (n = 31) | Perceptual | 0 | G1 (50.1) = Gc (54.1) | ||||

| Moderate ID area | Quantitative | 0 | G1 (45.7) = Gc (45.9) | |||||

| Memory | 0 | G1 (46.0) = Gc (49.4) | ||||||

| Motor | 0 | G1 (52.8) = Gc (55.6) | ||||||

| G1 (non-Iodized salt at 12 weeks)? | G1 (n = 24) | McCarthy | + | G1 (97.59) < Gc (105.36) * | ||||

| Gc (Iodized salt at 12 weeks) | Gc (n = 37) | Verbal | + | G1 (49.76) < Gc (54.96 ) * | ||||

| Moderate ID area | Perceptual | + | G1 (48.88) < Gc (53.84) * | |||||

| Quantitative | 0 | G1 (45.94) = Gc (47.04) | ||||||

| Memory | 0 | G1 (46.18) = Gc (49.80) | ||||||

| Motor | + | G1 (49.06) < Gc (56.72) * | ||||||

| Li et al., China [67] | Cohort Prospective | n = 111 | 25–30 months | tT4, fT4, TSH, TPOAb at 16–20 weeks | Bayley-I | + | G1, G2 (111.1) < Gc (120.2) | 0.75 (0.34, 1.17) |

| G1 & G2 (hypothyroid) | G1 (n = 18) | |||||||

| Gc (euthyroid: TSH < 4.21 mIU/L, normal fT4 and tT4, TPOAb− or tT4 > 101.79 nmol/L, normal TSH and fT4, TPOAb−) | G2 (n = 19) | |||||||

| Iodine sufficiency area | Gc (n = 74) | |||||||

| Man et al., USA [68,69] | Cohort Prospective | n = 326 | 8 months | BEI at 12–29 weeks | Bayley-I | + | G1 (95) vs. Gc (101) | 0.40 (0.10, 0.70) |

| Hypothyroxynemic mothers inadequately treated (G1), adequately treated (G2) | G1 (n = 55) | G1 (95) < G2 (102) ** | ||||||

| Gc (euthyroid mothers: BEI = 5.5 to 10.5 μg/100 mL) | G2 (n = 29) | |||||||

| Iodine sufficiency area | Gc (n = 242) | |||||||

| G1 (n = 23) | 4 years | Stanford-Binet | + | G1 (93 ± 15.9) vs. Gc (100) | 0.47 (0.03, 0.90) | |||

| G2 (n = 22) | G1 (93 ± 15.9) < G2 (102 ± 14.7) * | |||||||

| Gc (n = 227) | ||||||||

| Murcia et al., Spain [48] | Cohort Prospective | n = 674? | 11–16 months | Iodine intake, IS at 1st and 3rd trimester | Bayley-I | 0 | G1 (100.13 ± 15) = Gc (99.6 ± 16.5) | −0.02 (−0.18, 0.15) |

| Iodine intake from multivitamin supplement (Iodine) | G1(n = 467) | UIE, fT4, TSH, in 1st trimester | ||||||

| G1 (Iodine < 150 μg/day) | Gc(n = 222) | |||||||

| Gc (Iodine ≥ 150 μg/day)? | ||||||||

| G1 (UIE < 150 μg/L) | G1 (n = 357) | 0 | G1 (100.38 ± 15)= Gc (99.10 ± 15) | −0.09 (−0.24, 0.07) | ||||

| Gc (UIE > 150 μg/L) | Gc (n = 292) | |||||||

| G1 (non-Iodized salt) | G1 (n = 251) | 0 | G1 (100.3 ± 15.0) = Gc1 (99.8 ± 15.0) | −0.03 (−0.19, 0.12) | ||||

| Gc1 (Iodized salt) | Gc1 (n = 440) | |||||||

| G1 (TSH > 4 μU/mL) | G1(n = 24) | 0 | G1 (104.0 ± 13.5) = Gc (100.0 ± 14.8) | −0.27 (−0.70, 0.17) | ||||

| Gc (TSH ≤ 4 μU/mL) | Gc (n = 624) | |||||||

| Iodine sufficient and mild deficient areas | ||||||||

| Oken et al., USA [49] | Cohort Prospective | n = 500 | 6 months? | T4, TSH, TPOAb | Visual recognition memory (VRM) | 0 | 62.9 ± 16.0 | 0.10 estimated |

| Correlations with Mother’s history of thyroid disease | ||||||||

| Iodine sufficient area | 3 years | Peabody picture vocabulary test (PPVT) | + | 106 ± 13.2 | ||||

| Pop et al., Netherlands [70] | Cohort Prospective | n = 220 | fT4, TSH, TPOAb at 12 weeks of gestation | Bayley-I | 0 | G1 (110) = Gc (115) | 0.33 (−0.11, 0.78) | |

| G1 (fT4 ≤ 10th percentile) | G1 (n = 22) | Estimated from graphs | ||||||

| Gc (fT4 > 10th percentile) | Gc (n = 198) | |||||||

| Iodine sufficient area | ||||||||

| Pop et al., Netherlands [71] | G1 (fT4 ≤ 10th percentile) | G1 (n = 57) | 2 years | Bayley-I | + | G1 (98 ± 15) < Gc (106 ± 14) * | 0.53 (0.15, 0.91) | |

| Gc (50th ≤ maternal fT4 ≤ 90th) | Gc (n = 58) | |||||||

| Iodine sufficient area | ||||||||

| G1 (fT4 ≤ 10th percentile) | G1 (n = 57) | 2 years | Bayley-I | + | G1 (98 ± 15) < Gc (106 ± 14) * | 0.53 (0.15, 0.91) | ||

| Gc (50th ≤ maternal fT4 ≤ 90th) | Gc (n = 58) | |||||||

| Iodine sufficient area | ||||||||

| Radetti et al., Italy [72] | Cohort Prospective | n = 29 | 9 months | T4, fT4, T3, fT3, TSH, TBG, Tg, TPOAb? | Brunet-Lézine | 0 | G1 (99 ± 6.5) = Gc (98 ± 6.4) | −0.08 (0.91, 0.74) |

| G1 (treated for hypothyroidism) | G1 (n = 9) | Motor | 0 | |||||

| Gc (euthyroid: TSH < 4 mU/L with fT3 = 3.8 to 9.2 pmol/L and fT4 = 7.7 to 18 pmol/L) | Gc (n = 20) | Social dev. | 0 | |||||

| ID area | Speech | 0 | ||||||

| Eye-Hand coord | 0 | |||||||

| Smit et al., Netherlands [73] | Cohort Prospective | n = 20 | 6 months | T4, T3 and TSH at 1st, 2nd and 3rd trimester | Bayley-I | + | G1 (95.7 ± 14.7) < Gc (112.4 ± 13.2) * | 1.04 (−0.30 ,2.37) |

| G1 (hypo or subclinical hypothyroid) | G1 (n = 7) | |||||||

| G2 (hyper or subclinical hyperthyroid) | G2 (n = 7) | |||||||

| Gc (euthyroid: 1st trim: TSH = 0.3 to 2.0 mU/L; fT4 = 7.4 to 24.2 pmol/L; T3 = 2.0 to 3.6 nmol/L; 2nd trim: TSH = 0.5 to 2.3 mU/L; fT4 = 5.1 to 14.3 pmol/L; T3 = 2.2 to 3.8 nmol/L) | Gc (n = 6) | 12 months | Bayley-I | + | G1 (107.8 ± 15.3) < Gc (123.5 ± 17.8) * | 0.97 (−0.35, 2.30) | ||

| Iodine sufficient area | 24 months | Bayley-I | 0 | G1 (104.2 ± 31.0) = Gc (110.6 ± 29.6) | 0.40 (−0.85, 1.64) | |||

| Author, country | Design, groups | Sample size | Age at testing | Biological indicator | Mental development test | Outcomes | Group comparisons (mean ± SD) | Effect size d (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bongers-Schokking et al., Netherlands [74] | Cohort Prospective | n = 61 | 10–30 months | Newborn with CH (TSH, fT4, TBG,Tg) treated with thyroxine | Bayley-I | + | G1, G2, G3, G4 (106 ± 19) < G5, G6, G7, G8 (118 ± 11) *** | 0.80 (0.25, 1.33) |

| G1(severe CH early treat, high dose) | G1 (n = 7) | + | G1, G2 (112.19 ± 13) > G3, G4 (98.09 ± 21) | 0.91 (0.06, 1.76) | ||||

| G2 (severe CH early treat, low dose) | G2 (n = 9) | |||||||

| G3 (severe CH late treat, high dose)? | G3 (n = 6) | |||||||

| G4 (severe CH, late treat, low dose) | G4 (n = 5) | |||||||

| G5 (mild CH early treat, high dose) | G5 (n = 5) | |||||||

| G6 (mild CH early treat, low dose) | G6 (n = 7) | |||||||

| G7 (mild CH late treat, high dose) | G7 (n = 11) | |||||||

| G8 (mild CH, late treat, low dose) | G8 (n = 11) | |||||||

| Choudhury and Gordon, China [75] | Cohort Prospective | n = 275 | 7 months | Cord TSH | Fagan TII | 0 | G1 (58.9 ± 4.3) = Gc (59.6 ± 3.0) | 0.19 |

| G1 (TSH = 10.0–29.9 mU/L) | G1 (n = 94) | + | G2 (57.7 ± 5.6) < Gc (59.6 ± 3.0) | |||||

| G2 (TSH = 20.0–29.9 mU/L) | G2 (n = 82) | + | G3 (57.5 ± 3.1) < Gc (59.6 ± 3.0) | 0.66 (0.25, 1.08) | ||||

| G3 (TSH ≥ 30.0 mU/L) | G3 (n = 41) | |||||||

| Gc (controls: TSH < 5 mU/L) | Gc (n = 58) | |||||||

| Mild ID area | n = 135 | 13 months | Bayley-II | + | G1 (98.2 ± 8.3) < Gc (102.5 ± 8.2) * | 0.74 (0.14, 1.34) | ||

| + | G2 (98.7 ± 9.3) < Gc (102.5 ± 8.2) * | |||||||

| + | G3 (93.5 ± 11.1) < Gc (102.5 ± 8.2) * | |||||||

| Galan et al., Spain [47] | Cohort prospective | n = 61 | 37–47 months (Mean = 40) | Neonatal TSH | McCarthy | + | G1 (95.1 ± 12) < Gc (104.9) * | 0.81 (0.14, 1.5) |

| G1 (TSH ≥ 5 mU/L) | G1 (n = 12) | Verbal | + | G1 (49.2 ± 7.4) < Gc (56.9) * | 1.04 | |||

| Gc (TSH < 5 mU/L) | Gc (n = 49) | Perceptual | + | G1 (48.6 ± 8.7) < Gc (54.2) * | 0.64 | |||

| Moderate ID area | Quantitative | 0 | G1 (43.7 ± 7.2) = Gc (47.3) | 0.5 | ||||

| Memory | + | G1 (43.3 ± 8.1) < Gc (50.1) * | 0.84 | |||||

| Motor | 0 | G1 (50.9 ± 9.9) = Gc (55.1) | 0.42 | |||||

| Murcia et al., Spain [48] | Cohort Prospective | n = 680 | 11–16 months | Neonate TSH | Bayley-I | 0 | G1 (96.2 ± 17.0) = Gc (100.2 ± 14.9) | 0.27 (™0.11, 0.65) |

| G1 (TSH > 4 μU/mL) | G1 (n = 28) | |||||||

| Gc (TSH ≤ 4 μU/mL) | Gc (n = 652) | |||||||

| Iodine sufficient and mild deficient areas | ||||||||

| Oken et al., USA [49] | Cohort Prospective | n = 500 | 6 months? | Newborn T4 | Visual recognition memory (VRM) | 0 | 62.9 ± 16.0 | 0.10 estimated |

| Used newborn T4 as continuous variable | ||||||||

| Iodine sufficient area | 3 years | Peabody picture vocabulary test | 0 | 106.0 ± 13.2 | 0.10 estimated | |||

| Fine Motor | ||||||||

| 0 | 99.8 ± 11.8 | 0.00 estimated | ||||||

| Rovet et al., Canada [76] | Cohort Prospective | n = 80 | 12 months | All Newborn with CH -TSH; Bone age used to determine Iodine sufficiency as a fetus | Griffiths | 0 | G1 (110.5 ± 10.3) = Gc (113.3 ± 10.4) | 0.23 (™0.22, 0.68) |

| G1 (delayed skeletal maturity (fetal hypothyroidism) | G1 (n = 45) | Reynell language | 0 | No group means given | 0 | |||

| Gc (non-delayed skeletal maturity, i.e., likely iodine sufficient as a fetus) | Gc (n = 35) | |||||||

| All treated at birth | G1 (n = 31) | 2 years | Griffiths | + | G1 (109.0 ± 11.2) < Gc (118.9 ± 11.8) * | 0.81 (0.19, 1.43) | ||

| Gc (n = 18) | Reynell language | 0 | No group means given | 0 | ||||

| G1 (n = 28) | 3 years | Griffiths | + | G1 (111.9 ± 13.1) < Gc (121.0 ± 10.5) * | 0.75 (0.14, 1.36) | |||

| Gc (n = 20) | Reynell language | 0 | No group means given | 0 | ||||

| Beery-Buktenica fine motor | + | G1 (58.0 ± 5.1) < Gc (76.4 ± 4.0) * | 4 | |||||

| McCarthy percept | + | G (53.4 ± 2.2) < Gc (59.6 ± 2.0) * | 2.95 | |||||

| G1 (n = 20) | 4 years | McCarthy | + | G1 (103.1 ± 14.7) < Gc (114.6 ± 11.1) * | 0.80 (0.11, 1.5) | |||

| Gc (n = 17) | Reynell RecLang | + | G1 (™0.058 ± 1.2) < Gc (0.868 ± 0.8) ** | 0.93 | ||||

| Reynell ExpLang | + | G1 (™0.032 ± 1.0) < Gc (0.713 ± 1.0) * | 1.5 | |||||

| Beery-Buktenica fine motor | 0 | No group means given | 0 | |||||

| G1 (n = 18) | 5 years | WPPSI-I | + | G1 (97.8±15) < Gc (109.2±13.1) * | 0.74 (0.02,1.47) | |||

| Gc (n = 16) | Reynell RecLang | 0 | No group means given | 0 | ||||

| Reynell ExpLang | + | G1 (-0.233±1.2) < Gc (0.692±0.5) * | 0.93 | |||||

| Beery-Buktenica fine motor | + | G1 (42.3±5.6) < Gc (62.4±6.2) * | 3.35 | |||||

| Rovet et al., Canada [77], Study 1 | Cohort Prospective | G1 (n = 108) | 12–18 months | Newborn with CH (TSH) | Griffiths | 0 | G1 (111.0) = Gc (109.4) | ™0.11 (™0.41, 0.20) |

| G1(CH treated with 8–10 μg/kg l-thyroxine) | Gc (n = 71) | Bayley-I | + | G1 (106.4) < Gc (113.3) | 0.46 (0.15, 0.76) | |||

| Gc (Control siblings) | 2 years | Griffiths | 0 | G1 (112.8) = Gc (114.1) | 0.09 (™0.22, 0.39) | |||

| 3 years | Griffiths | 0 | G1 (114.8) = Gc (115.6) | 0.05 (™0.25, 0.36) | ||||

| Reynell Language | No group means given | |||||||

| 4 years | McCarthy | 0 | G1 (109.3) = Gc (114.0) | 0.31 (0.01, 0.62) | ||||

| Reynell Language | No group means given | |||||||

| 5 years | WPPSI | + | G1 (105.7) < Gc (114.5) * | 0.58 (0.28, 0.89) | ||||

| Reynell language | ||||||||

| Rovet et al., Canada [77] Study 2 | Cohort Prospective | n = 108 | 12 months | Newborn with CH (TSH) | Griffiths | 0 | G1 (110.9 ± 15) = Gc (112.7) | 0.12 |

| G1 (delayed skeletal maturity (fetal hypothyroidism)) | Bone age | |||||||

| Gc (non-delayed skeletal maturity) | 18 months | Bayley-I | + | G1 (102.5 ± 15) < Gc (116.3) * | 0.92 | |||

| 2 years | Griffiths | + | G1 (110.8 ± 15) < Gc (117.3) * | 0.43 | ||||

| 3 years | Griffiths | + | G1 (112.1 ± 15) < Gc (119.6) ** | 0.5 | ||||

| 4 years | McCarthy | + | G1 (107.3 ± 15) < Gc (114.7) * | 0.49 | ||||

| 5 years | WPPSI-I | + | G1 (104.0 ± 15) < Gc (109.8) * | 0.39 | ||||

| Tillotson et al., UK [78] | Cohort Prospective | n = 676 | 5 years | Newborn with CH treated vs. control | WPPSI | G1 (106.4 ± 15) = Gc (113.2) | 0.45 (0.30, 0.61) | |

| G1 (Congenital hypothyroid, treated) | G1 (n = 361) | |||||||

| Gc (Control) | Gc (n = 315) | |||||||

3.4.1. Intervention RCT

3.4.2. Intervention Non-RCT

3.4.3. Observational Cohort Prospective Studies Stratified by Maternal Iodine Status

3.4.4. Observational Cohort Prospective Studies Stratified by Newborn Iodine Status

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Bernal, J.; Pekonen, F. Ontogenesis of the nuclear 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine receptor in the human fetal brain. Endocrinology 1984, 114, 677–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J. Thyroid hormones and brain development. Vitam. Horm. 2005, 71, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.S. Principles of Nutritional Assessment, 2nd ed; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; p. 908. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer, J.H.; Schwartz, H.L.; Mariash, C.N.; Kinlaw, W.B.; Wong, N.C.; Freake, H.C. Advances in our understanding of thyroid hormone action at the cellular level. Endocr. Rev. 1987, 8, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, J.; Bernal, J.; Morte, B. Influence of thyroid hormones on maturation of rat cerebellar astrocytes. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2007, 25, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pedraza, P.E.; Obregon, M.J.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F.; del Rey, F.E.; de Escobar, G.M. Mechanisms of adaptation to iodine deficiency in rats: Thyroid status is tissue specific. Its relevance for man. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 2098–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregon, M.J.; Escobar del Rey, F.; Morreale de Escobar, G. The effects of iodine deficiency on thyroid hormone deiodination. Thyroid 2005, 15, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, R.M.; Ingbar, S.H. The effect of acute iodide depletion on thyroid function in man. J. Clin. Invest. 1965, 44, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeije, R.; Vanhaelst, L.; Golstein, J. Pituitary-thyroid axis during short term, mild and severe, iodine depletion in the rat. Horm. Metab. Res. 1978, 10, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, G.R.; Stanbury, J.B.; Fierro-Benitez, R. Neurological signs in congenital iodine-deficiency disorder (endemic cretinism). Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 1985, 27, 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Pharoah, P.O.; Buttfield, I.H.; Hetzel, B.S. Neurological damage to the fetus resulting from severe iodine deficiency during pregnancy. Lancet 1971, 1, 308–310. [Google Scholar]

- Hetzel, B.S. Iodine deficiency disorders (IDD) and their eradication. Lancet 1983, 2, 1126–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delange, F. The disorders induced by iodine deficiency. Thyroid 1994, 4, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B. The adverse effects of mild-to-moderate iodine deficiency during pregnancy and childhood: A review. Thyroid 2007, 17, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R.C.; Rose, M.C.; Skeaff, S.A.; Gray, A.R.; Morgan, K.M.; Ruffman, T. Iodine supplementation improves cognition in mildly iodine-deficient children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantham-McGregor, S.; Cheung, Y.B.; Cueto, S.; Glewwe, P.; Richter, L.; Strupp, B. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet 2007, 369, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S.P.; Wachs, T.D.; Gardner, J.M.; Lozoff, B.; Wasserman, G.A.; Pollitt, E.; Carter, J.A. Child development: Risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet 2007, 369, 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Untoro, J. Use of Oral Iodized Oil to Control Iodine Deficiency in Indonesia; Wageningen Agricultural University: Wageningen, Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Huda, S.N.; Grantham-McGregor, S.M.; Tomkins, A. Cognitive and motor functions of iodine-deficient but euthyroid children in Bangladesh do not benefit from iodized poppy seed oil (Lipiodol). J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista, A.; Barker, P.A.; Dunn, J.T.; Sanchez, M.; Kaiser, D.L. The effects of oral iodized oil on intelligence, thyroid status, and somatic growth in school-age children from an area of endemic goiter. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1982, 35, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, M.B.; Connolly, K.; Bozo, M.; Bridson, J.; Rohner, F.; Grimci, L. Iodine supplementation improves cognition in iodine-deficient schoolchildren in Albania: A randomized, controlled, double-blind study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, R.M. Effect of Iodine and Iron Supplementation on Physical, Psychomotor and Mental Development in Primary School Children in Malawi; Wageningen Agricultural University: Wageningen, Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pharoah, P.O.; Connolly, K.J. Effects of maternal iodine supplementation during pregnancy. Arch. Dis. Child. 1991, 66, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleichrodt, N.; Born, P.M. A Meta-Analysis of Research on Iodine and Its Relationship to Cognitive Development. In The Damaged Brain of Iodine Deficiency: Cognitive, Behavioral, Neuromotor and Educative Aspects; Stanbury, J.B., Ed.; Cognizant Communication Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef, H.; West, C.E.; Bleichrodt, N.; Dekker, P.H.; Born, M.P. Effects of Micronutrients During Pregnancy and Early Infancy on Mental and Psychomotor Development. In Micronutrient Deficiencies in the First Months of Life; Delange, F., West, J.K.P., Eds.; S. Karger AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2003; pp. 327–357. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, M.; Wang, D.; Watkins, W.E.; Gebski, V.; Yan, Y.Q.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.P. The effects of iodine on intelligence in children: A meta-analysis of studies conducted in China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 14, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald, L. Iodine Deficiency and Mental Development in Children. In Nutrition, Health, and Child Development: Research Advances and Policy Recommendations; Stationary Office Books: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 234–255. [Google Scholar]

- Melse-Boonstra, A.; Jaiswal, N. Iodine deficiency in pregnancy, infancy and childhood and its consequences for brain development. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 24, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.B. The effects of iodine deficiency in pregnancy and infancy. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2012, 26, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, W.J.; Verloove-Vanhorick, S.P.; Brand, R.; van den Brande, J.L. Transient hypothyroxinaemia associated with developmental delay in very preterm infants. Arch. Dis. Child. 1992, 67, 944–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuss, M.L.; Paneth, N.; Pinto-Martin, J.A.; Lorenz, J.M.; Susser, M. The relation of transient hypothyroxinemia in preterm infants to neurologic development at two years of age. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.; Rennie, J.; Baker, B.A.; Morley, R. Low plasma triiodothyronine concentrations and outcome in preterm infants. Arch. Dis. Child. 1988, 63, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Ouden, A.L.; Kok, J.H.; Verkerk, P.H.; Brand, R.; Verloove-Vanhorick, S.P. The relation between neonatal thyroxine levels and neurodevelopmental outcome at age 5 and 9 years in a national cohort of very preterm and/or very low birth weight infants. Pediatr. Res. 1996, 39, 142–145. [Google Scholar]

- Samsonova, L.; Ivakhnenko, V.; Ibragimova, G.; Ryabykh, A.; Naumenko, L.; Evdokimova, Y. Gestational hypothyroxinemia and cognitive function in offspring. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 2006, 36, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharoah, P.O.; Buttfield, I.H.; Hetzel, B.S. The effect of iodine prophylaxis on the incidence of endemic cretinism. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1972, 30, 201–221. [Google Scholar]

- Bleichrodt, N.; Escobar del Rey, F.; Morreale de Escobar, G.; Garcia, I.; Rubio, C. Iodine Deficiency, Implication for Mental and Psychomotor Development in Children. In Iodine and the Brain; DeLong, G.R., Robbins, J., Condliffe, P.G., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 269–287. [Google Scholar]

- Bogale, A.; Abebe, Y.; Stoecker, B.J.; Abuye, C.; Ketema, K.; Hambidge, K.M. Iodine status and cognitive function of women and their five year-old children in rural Sidama, southern Ethiopia. East Afr. J. Public Health 2009, 6, 296–299. [Google Scholar]

- Pop, V.J.; de Vries, E.; van Baar, A.L.; Waelkens, J.J.; de Rooy, H.A.; Horsten, M.; Donkers, M.M.; Komproe, I.H.; van Son, M.M.; Vader, H.L. Maternal thyroid peroxidase antibodies during pregnancy: A marker of impaired child development? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995, 80, 3561–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development; The Psychological Corp.: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley, N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development II; The Psychological Corp.: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, O.; Lézine, I.; Josse, D. Brunet-Lézine Revised: Psychomotor Scale of Early Childhood Development; (in French). Psychological Editions and Applications: Issy-les-Moulineaux, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Terman, L.; Merrill, M. Stanford-Binet: Intelligence Scale, Manual for the Third Revision, Form L–M; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Gesell, A. Gesell Development Schedules; Psychological Corp.: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, D. McCarthy Scales of Childrens Abilities; Psychological Association: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R. The Abilities of Young Children: A Comprehensive System of Mental Measurement for the First Eight Years of Life; Child Development Research Centre: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, I.; Fierro-Benitez, R.; Estrella, E.; Gomez, A.; Jaramillo, C.; Hermida, C.; Moncayo, F. The results of prophylaxis of endemic cretinism with iodized oil in rural Andean Ecuador. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1972, 30, 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Riano Galan, I.; Sanchez Martinez, P.; Pilar Mosteiro Diaz, M.; Rivas Crespo, M.F. Psycho-intellectual development of 3 year-old children with early gestational iodine deficiency. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 18, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Murcia, M.; Rebagliato, M.; Iniguez, C.; Lopez-Espinosa, M.J.; Estarlich, M.; Plaza, B.; Barona-Vilar, C.; Espada, M.; Vioque, J.; Ballester, F. Effect of iodine supplementation during pregnancy on infant neurodevelopment at 1 year of age. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 173, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oken, E.; Braverman, L.E.; Platek, D.; Mitchell, M.L.; Lee, S.L.; Pearce, E.N. Neonatal thyroxine, maternal thyroid function, and child cognition. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretell, E.A.; Torres, T.; Zenteno, V.; Cornejo, M. Prophylaxis of endemic goiter with iodized oil in rural Peru. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1972, 30, 249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Pretell, E.A.; Caceres, A. Impairment of Mental Development by Iodine Deficiency and its Correction. A Retrospective View of Studies in Peru. In The Damaged Brain of Iodine Deficiency: Cognitive, Behavioral, Neuromotor and Educative Aspects; Stanbury, J.B., Ed.; Cognizant Communication Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Thilly, C.H.; Roger, G.; Lagasse, R.; Tshibangu, D.; Vanderpas, J.B.; Berquist, H.; Nelson, G.; Ermans, A.M.; Delange, F. Fetomaternal Relationship, Fetal Hypothyroidism, and Psychomotor Retardation. In Role of Cassava in the Etiology of Endemic Goitre and Cretinism; Ermans, A.M., Mbulamoko, N.M., Delange, F., Ahluwalia, R., Eds.; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, Canada, 1980; pp. 111–182. [Google Scholar]

- Thilly, C.H.; Lagasse, R.; Roger, G.; Bourdoux, P.; Ermans, A.M. Impaired Fetal and Postanal Development and High Perinatal Death in a Severe Iodine Deficient Area. In Thyroid Research VIII: Proceedings of the Eighth International Thyroid Congress, Sydney, Australia, 3–8 February, 1980; Stockigt, J.R., Nagataki, S., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Thilly, C.H. Psychomotor Development in Regions with Endemic Goiter. In Fetal Brain Disorders: Recent Approaches to the Problem of Mental Deficiency; Hetzel, B.S., Smith, R.M., Eds.; Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 265–282. [Google Scholar]

- Thilly, C.H.; Swennen, B.; Moreno-Reyes, R.; Hindlet, J.Y.; Bourdoux, P.; Vanderpas, J.B. Maternal, Fetal, and Juvenile Hypothyroidism, Birth Weight and Infant Mortality in the Ethiopathogenesis of the Idd Spectra in Zaire And Malawi. In The Damaged Brain of Iodine Deficiency: Cognitive, Behavioral, Neuromotor and Educative Aspects; Stanbury, J.B., Ed.; Cognizant Communication Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Berbel, P.; Mestre, J.L.; Santamaria, A.; Palazon, I.; Franco, A.; Graells, M.; Gonzalez-Torga, A.; de Escobar, G.M. Delayed neurobehavioral development in children born to pregnant women with mild hypothyroxinemia during the first month of gestation: The importance of early iodine supplementation. Thyroid 2009, 19, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.Y.; Jiang, X.M.; Dou, Z.H.; Rakeman, M.A.; Zhang, M.L.; O’Donnell, K.; Ma, T.; Amette, K.; DeLong, N.; DeLong, G.R. Timing of vulnerability of the brain to iodine deficiency in endemic cretinism. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 1739–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro-Benitez, R.; Ramirez, I.; Suarez, J. Effect of iodine correction early in fetal life on intelligence quotient. A preliminary report. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1972, 30, 239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro-Benitez, R.; Ramirez, I.; Estrella, E.; Jaramillo, C.; Diaz, C.; Urresta, J. Iodized Oil in the Prevention of Endemic Goiter and Associated Defects in the Andean Region of Ecuador. I. Program Design, Effects on Goiter Prevalence, Thyroid Function, and Iodine Excretion. In Endemic Goiter; Report of the Meeting of the PAHO Scientific Group on Research in Endemic Goiter; Stanbury, J.B., Ed.; Pan American Health Organization, Pan American Sanitary Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 1968; pp. 306–340. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro-Benitez, R.; Ramirez, I.; Estrella, E.; Stanbury, J.B. The Role of Iodine in Intellectual Development in an Area of Endemic Goiter. In Endemic Goiter and Cretinism: Continuing Threats to World Health. Report of the IV Meeting of the PAHO Technical Group on Endemic Goiter; Dunn, J.T., Medeiros-Neto, G.A., Eds.; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 1974; pp. 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, I.; Fierro-Benitez, R.; Estrella, E.; Jaramillo, C.; Diaz, C.; Urresta, J. Iodized Oil in the Prevention of Endemic Goiter and Associated Defects in the Andean Region of Ecuador. II. Effects on Neuro-Motor Development and Somatic Growth in Children before Two Years. In Endemic Goiter; Report of the Meeting of the PAHO Scientific Group on Research in Endemic Goiter; Stanbury, J.B., Ed.; Pan American Health Organization, Pan American Sanitary Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 1968; pp. 341–359. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, L.S. A Retrospective View of Iodine Deficiency, Brain Development, and Behavior from Studies in Ecuador. In The Damaged Brain of Iodine Deficiency: Cognitive, Behavioral, Neuromotor and Educative Aspects; Stanbury, J.B., Ed.; Cognizant Communication Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Trowbridge, F.L. Intellectual assessment in primitive societies, with a preliminary report of a study of the effects of early iodine supplementation on intelligence. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1972, 30, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Pretell, E.A.; Moncloa, F.; Salinas, R.; Kawano, A.; Guerra-Garcia, R.; Gutierrez, L.; Beteta, L.; Pretell, J.; Wan, M. Prophylaxis and Treatment of Endemic Goiter in Peru with Iodized Oil. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1969, 29, 1586–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, I.; Carreira, M.; Santiago, P.; Muela, J.A.; Garcia-Fuentes, E.; Sanchez-Munoz, B.; Garriga, M.J.; Gonzalez-Fernandez, M.C.; Rodriguez, A.; Caballero, F.F.; et al. Effect of iodine prophylaxis during pregnancy on neurocognitive development of children during the first two years of life. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 3234–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costeira, M.J.; Oliveira, P.; Santos, N.C.; Ares, S.; Saenz-Rico, B.; de Escobar, G.M.; Palha, J.A. Psychomotor development of children from an iodine-deficient region. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Shan, Z.; Teng, W.; Yu, X.; Fan, C.; Teng, X.; Guo, R.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. Abnormalities of maternal thyroid function during pregnancy affect neuropsychological development of their children at 25–30 months. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 2010, 72, 825–829. [Google Scholar]

- Man, E.B. Thyroid function in pregnancy and infancy. Maternal hypothyroxinemia and retardation of progeny. CRC Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1972, 3, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, E.B.; Brown, J.F.; Serunian, S.A. Maternal hypothyroxinemia: Psychoneurological deficits of progeny. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1991, 21, 227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Pop, V.J.; Kuijpens, J.L.; van Baar, A.L.; Verkerk, G.; van Son, M.M.; de Vijlder, J.J.; Vulsma, T.; Wiersinga, W.M.; Drexhage, H.A.; Vader, H.L. Low maternal free thyroxine concentrations during early pregnancy are associated with impaired psychomotor development in infancy. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 1999, 50, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Pop, V.J.; Brouwers, E.P.; Vader, H.L.; Vulsma, T.; van Baar, A.L.; de Vijlder, J.J. Maternal hypothyroxinaemia during early pregnancy and subsequent child development: A 3-year follow-up study. Clin. Endocrinol. 2003, 59, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radetti, G.; Gentili, L.; Paganini, C.; Oberhofer, R.; Deluggi, I.; Delucca, A. Psychomotor and audiological assessment of infants born to mothers with subclinical thyroid dysfunction in early pregnancy. Minerva Pediatr. 2000, 52, 691–698. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, B.J.; Kok, J.H.; Vulsma, T.; Briet, J.M.; Boer, K.; Wiersinga, W.M. Neurologic development of the newborn and young child in relation to maternal thyroid function. Acta Paediatr. 2000, 89, 291–295. [Google Scholar]

- Bongers-Schokking, J.J.; Koot, H.M.; Wiersma, D.; Verkerk, P.H.; de Muinck Keizer-Schrama, S.M. Influence of timing and dose of thyroid hormone replacement on development in infants with congenital hypothyroidism. J. Pediatr. 2000, 136, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, N.; Gorman, K.S. Subclinical prenatal iodine deficiency negatively affects infant development in Northern China. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3162–3165. [Google Scholar]

- Rovet, J.; Ehrlich, R.; Sorbara, D. Intellectual outcome in children with fetal hypothyroidism. J. Pediatr. 1987, 110, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovet, J.F.; Ehrlich, R.M.; Sorbara, D.L. Neurodevelopment in infants and preschool children with congenital hypothyroidism: etiological and treatment factors affecting outcome. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 1992, 17, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillotson, S.L.; Fuggle, P.W.; Smith, I.; Ades, A.E.; Grant, D.B. Relation between biochemical severity and intelligence in early treated congenital hypothyroidism: a threshold effect. BMJ 1994, 309, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, S.N.; Grantham-McGregor, S.M.; Rahman, K.M.; Tomkins, A. Biochemical hypothyroidism secondary to iodine deficiency is associated with poor school achievement and cognition in Bangladeshi children. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 980–987. [Google Scholar]

- Vierhaus, M.; Lohaus, A.; Kolling, T.; Teubert, M.; Keller, H.; Fassbender, I.; Freitag, C.; Goertz, C.; Graf, F.; Lamm, B.; et al. The development of 3- to 9-month-old infants in two cultural contexts: Bayley longitudinal results for Cameroonian and German infants. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 8, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.-F.; Aihaiti; Zhao, H.-X.; Lin, J.; Jiang, J.-Y.; Maimaiti; Aiken. The relationship of a low-iodine and high-fluoride environment to subclinical cretinism in Xinjiang. Iodine Defic. Disord. Newsl. 1991, 7, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, K.J.; Rakeman, M.A.; Zhi-Hong, D.; Xue-Yi, C.; Mei, Z.Y.; DeLong, N.; Brenner, G.; Tai, M.; Dong, W.; DeLong, G.R. Effects of iodine supplementation during pregnancy on child growth and development at school age. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2002, 44, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Briel, T.; West, C.E.; Bleichrodt, N.; van de Vijver, F.J.; Ategbo, E.A.; Hautvast, J.G. Improved iodine status is associated with improved mental performance of schoolchildren in Benin. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, K.J.; Pharoah, P.O.; Hetzel, B.S. Fetal iodine deficiency and motor performance during childhood. Lancet 1979, 2, 1149–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development III; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cleare, A.J.; McGregor, A.; O’Keane, V. Neuroendocrine evidence for an association between hypothyroidism, reduced central 5-HT activity and depression. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 1995, 43, 713–719. [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty, J.J., Jr.; Prange, A.J., Jr. Borderline hypothyroidism and depression. Annu. Rev. Med. 1995, 46, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.H.; Corwyn, R.F. Caring for children around the world: A view from HOME. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2005, 29, 468–478. [Google Scholar]

- Harpham, T.; Huttly, S.; de Silva, M.J.; Abramsky, T. Maternal mental health and child nutritional status in four developing countries. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 1060–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servili, C.; Medhin, G.; Hanlon, C.; Tomlinson, M.; Worku, B.; Baheretibeb, Y.; Dewey, M.; Alem, A.; Prince, M. Maternal common mental disorders and infant development in Ethiopia: The P-MaMiE Birth Cohort. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund; World Summit for Children—Mid Decade Goal: Iodine Deficiency Disorders (IDD); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994; p. 12.

- Andersson, M.; de Benoist, B.; Rogers, L. Epidemiology of iodine deficiency: Salt iodisation and iodine status. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleti, M.; Lo Presti, V.P.; Campolo, M.C.; Mattina, F.; Galletti, M.; Mandolfino, M.; Violi, M.A.; Giorgianni, G.; de Domenico, D.; Trimarchi, F.; et al. Iodine prophylaxis using iodized salt and risk of maternal thyroid failure in conditions of mild iodine deficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 2616–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untoro, J.; Mangasaryan, N.; de Benoist, B.; Darnton-Hill, I. Reaching optimal iodine nutrition in pregnant and lactating women and young children: Programmatic recommendations. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 1527–1529. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Bougma, K.; Aboud, F.E.; Harding, K.B.; Marquis, G.S. Iodine and Mental Development of Children 5 Years Old and Under: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1384-1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5041384

Bougma K, Aboud FE, Harding KB, Marquis GS. Iodine and Mental Development of Children 5 Years Old and Under: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2013; 5(4):1384-1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5041384

Chicago/Turabian StyleBougma, Karim, Frances E. Aboud, Kimberly B. Harding, and Grace S. Marquis. 2013. "Iodine and Mental Development of Children 5 Years Old and Under: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 5, no. 4: 1384-1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5041384

APA StyleBougma, K., Aboud, F. E., Harding, K. B., & Marquis, G. S. (2013). Iodine and Mental Development of Children 5 Years Old and Under: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 5(4), 1384-1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5041384