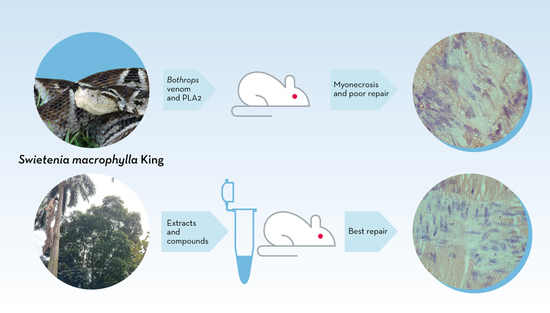

Effects of Two Fractions of Swietenia macrophylla and Catechin on Muscle Damage Induced by Bothrops Venom and PLA2

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. PLA2-Induced Necrosis and Its Neutralization by Fractions F4 and F6 and Catechin

2.2. Infiltration of Inflammatory Cells

2.3. Fibrosis

2.4. Neuromuscular Activity of B. Marmoratus Venom

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Venoms and PLA2

4.3. Extracts and Compounds of S. macrophylla

4.4. Histological Analysis

4.5. Mouse Phrenic Nerve-Diaphragm Preparation

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chippaux, J.P. Snake-bites: Appraisal of the global situation. Bull. World Health Organ. 1998, 76, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasturiratne, A.; Wickremasinghe, A.R.; De Silva, N.; Gunawardena, N.K.; Pathmeswaran, A.; Premaratna, R.; Savioli, L.; Lalloo, D.G.; De Silva, H.J. The global burden of snakebite: A literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, 1591–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, J.M.; Calvete, J.J.; Habib, A.G.; Harrison, R.A.; Williams, D.J.; Warrell, D.A. Snakebite envenoming. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León, L. Informe del Evento Accidente Ofídico; Instituto Nacional de Salud: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Warrell, D.A. Snakebites in Central and South America: Epidemiology, clinical features and clinical management. In Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere; Campbell, J.A., Lamar, W.W., Eds.; Comstock Publishing Associates/Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 709–761, ISBN-13: 978-0801441417. [Google Scholar]

- França, F.O.S.; Málaque, C.M.S. Acidente botrópico. In Animais Peçonhentos do Brasil. Biologia, Clínica e Terapêutica dos Acidentes, 2nd ed.; Cardoso, J.L.C., França, F.O.S., Wen, F.H., Málaque, C.M.S., Haddad, V., Jr., Eds.; Sarvier: São Paulo, Brazil, 2009; pp. 81–95. ISBN 9788573781946. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-Patiño, R. Snake bites in Colombia. In Clinical Toxicology in Australia, Europe and Americas; Gopalakrishnakone, P., Vogel, C.M., Seifert, S.A., Tambrougi, D.V., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media B.V.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, J.M.; Ownby, C.L. Skeletal muscle degeneration induced by venom phospholipases A2: Insights into the mechanisms of local and systemic myotoxicity. Toxicon 2003, 42, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucaretchi, F.; de Capitani, E.M.; Hyslop, S.; Mello, S.M.; Madureira, P.R.; Zanardi, V.; Ferreira, D.M.; Meirelles, G.V.; Fernandes, L.C.R. Compartment syndrome after Bothrops jararaca snakebite: Monitoring, treatment, and outcome. Clin. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, J.M.; Lomonte, B. Efectos locales en el envenenamiento ofídico en América Latina. In Animais Peçonhentos do Brasil. Biologia, Clínica e Terapêutica dos Acidentes, 2nd ed.; Cardoso, J.L.C., França, F.O.S., Wen, F.H., Málaque, C.M.S., Haddad, V., Jr., Eds.; Sarvier: São Paulo, Brazil, 2009; pp. 352–365. ISBN 9788573781946. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, R.; Cabalceta, C.; Saravia-Otten, P.; Chaves, A.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Rucavado, A. Poor regenerative outcome after skeletal muscle necrosis induced by Bothrops asper venom: Alterations in microvasculature and nerves. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B.J.; Valentine, B.A. Muscle and tendon. In Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 6th ed.; Maxie, M.G., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 164–249. [Google Scholar]

- Otero, R. Seroterapia antivenenosa. Ventajas del uso de antivenenos del tipo IgG, F(ab’)2 o Fab en picaduras de escorpiones y mordeduras de serpientes. Rev. Colomb. Pediatr. 2002, 37, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Picolo, G.; Chacur, M.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Teixeira, C.F.P.; Cury, Y. Evaluation of antivenoms in the neutralization of hyperalgesia and edema induced by Bothrops jararaca and Bothrops asper snake venoms. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2002, 35, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.Z.; Maiorano, V.A.; Marcussi, S.; Sant’Ana, C.D.; Januário, A.H.; Lourenço, M.V.; Sampaio, S.V.; França, S.C.; Pereira, P.S.; Soares, A.M. Anticoagulant and antifibrinogenolytic properties of the aqueous extract from Bauhinia forficata against snake venoms. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 98, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.; Lomonte, B.; León, G.; Rucavado, A.; Chaves, F.; Angulo, Y. Trends in snakebite envenomation therapy: Scientific, technological and public health considerations. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13, 2935–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Patiño, R.; Segura, A.; Herrera, M.; Angulo, Y.; León, G.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Barona, J.; Estrada, S.; Pereañez, A.; Quintana, J.C.; et al. Comparative study of the efficacy and safety of two polyvalent, caprylic acid fractionated [IgG and F(ab’)2] antivenoms, in Bothrops asper bites in Colombia. Toxicon 2012, 59, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifert, S.A.; Boyer, L.V. Recurrence phenomena after immunoglobulin therapy for snake envenomations: Part 1. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of immunoglobulin antivenoms and related antibodies. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2001, 37, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanhajariya, S.; Duffull, S.B.; Isbister, G.K. Pharmacokinetics of snake venom. Toxins 2018, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coe, F.G.; Anderson, G.J. Snakebite ethnopharmacopoeia of eastern Nicaragua. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 96, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.M.; Ticli, F.K.; Marcussi, S.; Lourenço, M.V.; Januário, A.H.; Sampaio, S.V.; Giglio, J.R.; Lomonte, B.; Pereira, P.S. Medicinal plants within inhibitory properties against snake venoms. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 2625–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo, Y.; Lomonte, B. Biochemistry and toxicology of toxins purified from the venom of the snake Bothrops asper. Toxicon 2009, 54, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereañez, J.A.; Lobo-Echeverri, T.; Rojano, B.; Vargas, L.; Fernandez, M.; Gaviria, C.A.; Núñez, V. Correlation of the inhibitory activity of phospholipase A2 snake venom and the antioxidant activity of Colombian plant extracts. Braz. J. Pharmacogn. 2010, 20, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage-Melim, L.I.; Sampaio, S.V.; Taft, C.A.; Silva, C.H. Phospholipase A2 inhibitors isolated from medicinal plants: Alternative treatment against snakebites. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, P.; Howes, M.J.R. Medicinal plants used to treat snakebite in Central America: Review and assessment of scientific evidence. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 199, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, M.; Tagesson, C. Flavonoids as phospholipase A2 inhibitors: Importance of their structure for selective inhibition of group II phospholipase A2. Inflammation 1997, 21, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mors, W.; Do Nascimento, M.; Pereira, B.; Pereira, N. Plant natural products active against snake bite—The molecular approach. Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pithayanukul, P.; Ruenraroengsak, P.; Bavovada, R.; Pakmanee, N.; Suttisri, R.; Saen-Oon, S. Inhibition of Naja kaouthia venom activities by plant polyphenols. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 97, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyama, D.; Marangoni, S.; Diz-Filho, E.; Oliveira, S.; Toyama, M. Effect of umbelliferone (7-hydroxycoumarin, 7-HOC) on the enzymatic, edematogenic and necrotic activities of secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) isolated from Crotalus durissus collilineatus venom. Toxicon 2009, 53, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhosh, M.S.; Hemshekhar, M.; Sunitha, K.; Thushara, R.M.; Jnaneshwari, S.; Kemparaju, K.; Girish, K.S. Snake venom induced local toxicities: Plant secondary metabolites as an auxiliary therapy. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishijima, C.M.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Silva, M.A.; Lopes-Ferreira, M.; Vilegas, W.; Hiruma-Lima, C.A. Anti-hemorrhagic activity of four Brazilian vegetable species against Bothrops jararaca venom. Molecules 2009, 14, 1072–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.M.; Félix-Silva, J.; da Cunha, L.M.; Gomes, J.A.; Siqueira, E.M.; Gimenes, L.P.; Lopes, N.P.; Soares, L.A.; Fernandes-Pedrosa, M.F.; Zucolotto, S.M. Inhibitory effects of hydroethanolic leaf extracts of Kalanchoe brasiliensis and Kalanchoe pinnata (Crassulaceae) against local effects induced by Bothrops jararaca snake venom. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, A.L.; Oliveira, A.P.; Ruppelt, B.M.; de Araújo, E.R.A.; Santos, M.G.; Caldas, G.R.; Muylaert, F.F.; Amendoeira, F.C.; Ferraris, F.K.; de Souza, C.M.V.; et al. Protective effect of Myrsine parvifolia plant extract against the inflammatory process induced by Bothrops jararaca snake venom. Toxicon 2018, 157, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preciado, L.M.; Comer, J.; Núñez, V.; Rey-Súarez, P.; Pereañez, J.A. Inhibition of a snake venom metalloproteinase by the flavonoid myricetin. Molecules 2018, 23, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachetto, A.T.A.; Rosa, J.G.; Santoro, M.L. Rutin (quercetin-3-rutinoside) modulates the hemostatic disturbances and redox imbalance induced by Bothrops jararaca snake venom in mice. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, L.H.F.; Mendes, M.M.; Fernandes, R.S.; Costa, T.R.; Hage-Melim, L.I.S.; Sousa, M.A.; Hamaguchi, A.; Homsi-Brandeburgo, M.I.; Franca, S.C.; Silva, C.H.; et al. Protective effect of Schizolobium parahyba flavonoids against snake venoms and isolated toxins. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 2566–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, U.R.; Das, N.P. Inhibitory effects of flavonoids on several venom hyaluronidases. Experientia 1991, 47, 1196–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghadamtousi, S.; Goh, B.; Chan, C.; Shabab, T.; Kadir, H. Biological activities and phytochemicals of Swietenia macrophylla King. Molecules 2013, 18, 10465–10483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ch’ng, Y.S.; Loh, Y.C.; Tan, C.S.; Ahmad, M.; Asmawi, M.Z.; Wan Omar, W.M.; Yam, M.F. Vasodilation and antihypertensive activities of Swietenia macrophylla (Mahogany) seed extract. J. Med. Food 2018, 21, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdy, G.; DeWalt, S.J.; Chávez De Michel, L.R.; Roca, A.; Deharo, E.; Muñoz, V.; Balderrama, L.; Quenevo, C.; Gimenez, A. Medicinal plants uses of the Tacana, an Amazonian Bolivian ethnic group. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 70, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preciado, L.; Pereañez, J.; Núñez, V.; Lobo-Echeverri, T. Characterization of the most promising fraction of Swietenia macrophylla active against myotoxic phospholipases A2: Identification of catechin as one of the active compounds. Vitae 2016, 23, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada Arias, S.; Rey-Suárez, P.; Pereáñez, J.A.; Acosta, C.; Rojas, M.; dos Santos, L.D.; Ferreira, R.S., Jr.; Núñez, V. Isolation and functional characterization of an acidic myotoxic phospholipase A2 from Colombian Bothrops asper venom. Toxins 2017, 9, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.M.; Rucavado, A.; Escalante, T.; Herrera, C.; Fernández, J.; Lomonte, B.; Fox, J.W. Unresolved issues in the understanding of the pathogenesis of local tissue damage induced by snake venoms. Toxicon 2018, 148, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allbook, D. Skeletal muscle regeneration. Muscle Nerve 1981, 4, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.; Faulkner, J. The regeneration of skeletal muscle fibers following injury: A review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1983, 15, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ticli, F.K.; Hage, L.I.; Cambraia, R.S.; Pereira, P.S.; Magro, A.J.; Fontes, M.R.; Stábeli, R.G.; Giglio, J.R.; França, S.C.; Soares, A.M.; et al. Rosmarinic acid, a new snake venom phospholipase A2 inhibitor from Cordia verbenacea (Boraginaceae): Antiserum action potentiation and molecular interaction. Toxicon 2005, 46, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrim, C.A.; De Oliveira, S.C.B.; Diz Filho, E.B.S.; Fonseca, F.V.; Baldissera, L., Jr.; Antunes, E.; Ximenes, R.M.; Monteiro, H.S.; Rabello, M.M.; Hernandes, M.Z.; et al. Quercetin as an inhibitor of snake venom secretory phospholipase A2. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2011, 189, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassino, A.; Czaika, M.H.G. Biología del daño y reparación muscular. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2000, 36, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.; Zamunér, S.R.; Juliani, J.P.; Fernandes, C.M.; Cruz-Höfling, M.A.; Fernandes, I.; Chavez, F.; Gutiérrez, J.M. Neutrophils do not contribute to local tissue damage, but play a key role in skeletal muscle regeneration in mice. Muscle Nerve 2003, 28, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, T.; Maley, M.; Grounds, M.; Papadimitriou, J. The role of macrophages in skeletal muscle regeneration with particular reference to chemotaxis. Exp. Cell Res. 1993, 207, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamuner, S.R.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Muscará, M.N.; Teixeira, S.A.; Teixeira, C.F.P. Bothrops asper and Bothrops jararaca snake venoms trigger microbicidal functions of peritoneal leukocytes in vivo. Toxicon 2001, 39, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaariainen, M.; Jarvinen, T.; Jarvinen, M.; Rantanen, J.; Kalimo, H. Relation between myofibers and connective tissue during muscle injury repair. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2000, 10, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanigawa, T.; Kanazawa, S.; Ichibori, R.; Fujiwara, T.; Magome, T.; Shingaki, K.; Miyata, S.; Hata, Y.; Tomita, K.; Matsuda, K.; et al. (+)-Catechin protects dermal fibroblasts against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Santos, L.F.; Stolfo, A.; Calloni, C.; Salvador, M. Catechin and epicatechin reduce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress induced by amiodarone in human lung fibroblasts. J. Arrhythm. 2017, 33, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wong, K.; Giles, A.; Jiang, J.; Lee, J.W.; Adams, A.C.; Kharitonenkov, A.; Yang, Q.; Gao, B.; Guarente, L.; et al. Hepatic SIRT1 attenuates hepatic steatosis and controls energy balance in mice by inducing fibroblast growth factor 21. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendler, L.; Zádor, E.; Ver Heyen, M.; Dux, L.; Wuytack, F. Myostatin levels in regenerating rat muscles and in myogenic cell cultures. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2000, 21, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanouchi, K.; Soeta, C.; Naito, K.; Tojo, H. Expression of myostatin gene in regenerating skeletal muscle of the rat and its localization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 270, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, K.; Badlani, N.; Usas, A.; Riano, F.; Fu, F.; Huard, J. The use of an antifibrosis agent to improve muscle recovery after laceration. Am. J. Sports Med. 2001, 29, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, R.; Carneiro, I.; Arce, V.M.; Devesa, J. Myostatin is an inhibitor of myogenic differentiation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2002, 282, C993–C999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Huard, J. Differentiation of muscle-derived cells into myofibroblasts in injured skeletal muscle. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 161, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.E.; Bhasin, S.; Artaza, J.; Byhower, F.; Azam, M.; Willard, D.H., Jr.; Kull, F.C., Jr.; Gonzalez-Cadavid, N. Myostatin inhibits cell proliferation and protein synthesis in C2C12 muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 280, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, J.I.; Cardoso, F.F.; Soares, A.M.; Dal Pai Silva, M.; Gallacci, M.; Fontes, M.R. Structural and functional studies of a bothropic myotoxin complexed to rosmarinic acid: New insights into Lys49-PLA2 inhibition. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao-Duque, A.M.; Rodríguez, B.J.; Pereañez, J.A.; Lobo-Echeverri, T.; Núñez Rangel, V. Acute oral toxicity from a fraction rich in phenolic compounds from the leaf extract of Swietenia macrophylla King in a murine model. Vitae 2017, 24, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floriano, R.; Carregari, V.; de Abreu, V.; Kenzo-Kagawa, B.; Ponce-Soto, L.; Cruz-Höfling, M.; Hyslop, S.; Marangoni, S.; Rodrigues-Simioni, L. Pharmacological study of a new Asp49 phospholipase A2 (Bbil-TX) isolated from Bothriopsis bilineata smargadina (forest viper) venom in vertebrate neuromuscular preparations. Toxicon 2013, 69, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Days Post-Injection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 7 | 14 | 28 | |

| BaColPLA2 vs Saline | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| BaColPLA2 vs F4 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| BaColPLA2 vs F6 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| BaColPLA2 vs Cat | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| BaColPLA2 vs BaColPLA2+F4 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.01 |

| BaColPLA2 vs BaColPLA2+F6 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| BaColPLA2 vs BaColPLA2+Cat | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

| BaColPLA2+F4 vs BaColPLA2+F6 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ns | ns |

| BaColPLA2+F4 vs BaColPLA2+Cat | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ns | ns |

| BaColPLA2+F6 vs BaColPLA2+Cat | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.01 | ns |

| Treatment | Days Post-Injection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 7 | 14 | 28 | |

| BaColPLA2 vs Saline | p < 0.001 | ns | p < 0.05 | ns |

| BaColPLA2 vs F4 | p < 0.001 | ns | p < 0.05 | ns |

| BaColPLA2 vs F6 | p < 0.001 | ns | ns | ns |

| BaColPLA2 vs Cat | p < 0.001 | ns | ns | ns |

| BaColPLA2 vs BaColPLA2+F4 | p < 0.01 | ns | ns | ns |

| BaColPLA2 vs BaColPLA2+F6 | p < 0.01 | ns | ns | ns |

| BaColPLA2 vs BaColPLA2+Cat | p < 0.001 | ns | p < 0.05 | ns |

| BaColPLA2+F4 vsBaColPLA2+F6 | p < 0.05 | ns | ns | ns |

| BaColPLA2+F4 vs BaColPLA2+Cat | p < 0.01 | ns | ns | ns |

| BaColPLA2+F6 vs BaColPLA2+Cat | p < 0.001 | ns | ns | ns |

| Score | Extent of Fibrosis | Interpretation of Findings |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Absent | No collagen deposition |

| 2 | Focal, 15% of tissue affected | Medium fibrosis |

| 3 | Focal, 15–35% of tissue affected | Medium to moderate fibrosis |

| 4 | Multifocal, 35–50% of tissue affected | Moderate fibrosis |

| 5 | Multifocal, 50–85% of tissue affected | Moderate to severe fibrosis |

| 6 | Extensive, diffuse, 85–100% of tissue affected | Severe fibrosis |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arias, S.P.; de Jesús Rodríguez, B.; Lobo-Echeverri, T.; Ramos, R.S.; Hyslop, S.; Rangel, V.N. Effects of Two Fractions of Swietenia macrophylla and Catechin on Muscle Damage Induced by Bothrops Venom and PLA2. Toxins 2019, 11, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11010040

Arias SP, de Jesús Rodríguez B, Lobo-Echeverri T, Ramos RS, Hyslop S, Rangel VN. Effects of Two Fractions of Swietenia macrophylla and Catechin on Muscle Damage Induced by Bothrops Venom and PLA2. Toxins. 2019; 11(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleArias, Silvia Posada, Berardo de Jesús Rodríguez, Tatiana Lobo-Echeverri, Raphael Shezaro Ramos, Stephen Hyslop, and Vitelbina Núñez Rangel. 2019. "Effects of Two Fractions of Swietenia macrophylla and Catechin on Muscle Damage Induced by Bothrops Venom and PLA2" Toxins 11, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11010040

APA StyleArias, S. P., de Jesús Rodríguez, B., Lobo-Echeverri, T., Ramos, R. S., Hyslop, S., & Rangel, V. N. (2019). Effects of Two Fractions of Swietenia macrophylla and Catechin on Muscle Damage Induced by Bothrops Venom and PLA2. Toxins, 11(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11010040