Grafted Microparticles Based on Glycidyl Methacrylate, Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate and Sodium Hyaluronate: Synthesis, Characterization, Adsorption and Release Studies of Metronidazole

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Synthesis of Precursor Microparticles

- Aqueous phase containing a polymeric stabilizer (2 wt% mixture of PVA and gelatine) and NaCl (3 wt%);

- Organic phase is formed by GMA (70% mol), HEMA (20% mol), crosslinking agents (10% mol of EGDMA, DEGDMA or TEGDMA), BOP and butyl acetate at a dilution of D = 0.6.

2.2.2. Synthesis of Hybrid Microparticles

2.2.3. Infrared Spectroscopy

2.2.4. Epoxy Group Content

2.2.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.2.7. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

2.2.8. Dimensional Analysis of Precursor/Hybrid Microparticles

2.2.9. Specific Parameters for the Characterization of the Morphology of Porous Structure

2.2.10. Swelling Studies

2.2.11. Bach Adsorption Studies

2.2.12. Drug Release Studies

3. Results and Discussion

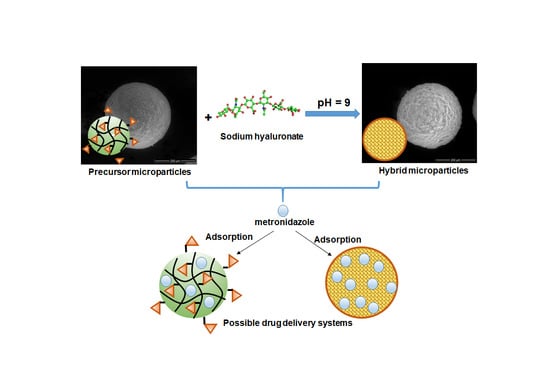

3.1. Synthesis of Precursor/Hybrid Microparticles

Optimization of the Grafting Reaction

- The amount of grafted HA increases with the concentration of the polymer solution up to a value of 0.6%, after which equilibrium is reached. This behavior is due to the fact that as the concentration of the HA solution increases, the number of hydroxyl groups that will react in a basic medium with the epoxy groups increases, leading to the formation of a covalent ether -CH2-O-HA bond. Additionally, at low concentrations, the viscosity of HA solutions is lower, ensuring a more uniform stirring and better accessibility for the epoxy groups on the surface of the precursor microparticles;

- Increasing the temperature of the reaction medium has the effect of decreasing the viscosity of the reaction medium and increasing the mobility of the polymer chains, leading to a better interaction between the -OH groups belonging to HA and the epoxy groups on the surface of the precursor microparticles, and thus to a higher amount of grafted HA. Temperature is also known to increase the reaction rate and to favor higher yields for most chemical reactions;

- Increasing the reaction time to 6 h resulted in an increase in the amount of grafted HA;

- Another important parameter of the grafting process is the pH of the reaction. In a basic medium, the epoxy ring opening reaction by the -OH group proceeds by an SN2 mechanism and the -OH group is formed at the most substituted atom in the ring. In an acidic environment, the reaction proceeds through the SN1 mechanism, leading to the formation of -OH at the methylene group of the ring, and the rest of the HA molecule, which is huge in volume, encounters significant steric hindrances, making it difficult to bind to the secondary carbon atom of the ring. Thus, the epoxide cycle opening reaction resulting in the grafting of HA to the polymer particles will be increasingly favored by the increasing pH, which intensifies the nucleophilic attack (SN2) of -OH from the polysaccharide to the epoxy ring.

3.2. Structural Characterization

3.2.1. FTIR Spectroscopy

- The values of the specific absorption band areas at the wavenumber 3450 cm−1 are higher for the hybrid microparticles (AAEHA = 46.95 cm−1, AADHA = 28.95 cm−1, AATHA = 78.00 cm−1) compared to the values of similar absorption band areas corresponding to the precursor microparticles (AAE = 20.97 cm−1, AAD = 13.73 cm−1 and AAT = 67.56 cm−1). The higher values of the absorption band of the hybrid microparticles are due to the presence of sodium hyaluronate, which has several hydroxyl groups in its structure;

- The increase in the values of the adsorption band area at 1151 cm−1 in the case of the hybrid microparticles is due to the formation of new ether bonds by grafting HA to the epoxy groups from the GMA structure;

- In the case of the hybrid microparticles, a decrease in the values of the specific areas of the absorption bands is observed from the wavenumber 907 cm−1, due to the grafting reaction of HA by the opening of the epoxy ring in a basic medium.

3.2.2. Dimensional Analysis of Precursor/Hybrid Microparticles

3.2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis

3.2.4. Determination of Epoxy Groups

3.3. Morphological Characterization

3.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3.3.2. Atomic Force Microscopy

3.3.3. Specific Parameters for Characterizing the Morphology of Porous Structures

- from 314 to 238 nm for the AE–AEHA microparticle system;

- from 369 to 280 nm for the AD–ADHA microparticle system;

- and from 265 to 176 nm for the AT–ATHA microparticle system.

3.4. Swelling Capacity of Precursor/Hybrid Microparticles in Aqueous Media

- The second-order kinetic model using the equations [25]:

- 2.

- Korsmeyer–Peppas model. The linear form of the Korsmeyer–Peppas equation [27] is given as:

3.5. Metronidazole Adsorption and Release Studies

3.5.1. Adsorption Equilibrium Studies

- Two parameter isotherm models:

- Langmuir isotherm [28]:

- Freundlich isotherm [29]:

- Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm [30]:where qe is the metronidazole amount adsorbed at equilibrium (mg·g−1); qm is the maximum adsorption capacity (mg·g−1); KL is the Langmuir constant that reflects the affinity between the adsorbate and the adsorbent (L·g−1); KF is the adsorption capacity for a unit’s equilibrium concentration (L·g−1); 1/nF is a constant that suggests the favorability and capacity of the adsorbent–adsorbate system; ε is the Polanyi potential; and KD is the constant which is related to the calculated average sorption energy E (kJ·mol−1).The constant KD can give the valuable information regarding the mean energy of adsorption by the equation:

- 2.

- Three-parameter isotherm models:

- Sips isotherm [31]:

- Khan isotherm [32]:where KS is the Sips constant (L·mg−1); nS is the Sips model exponent; bK is the Khan model constant; and nK is the Khan model exponent.

- The values of the maximum adsorption capacity, qm, calculated based on the Langmuir, Dubinin–Radushkevich, Sips and Khan models, are close to the experimental values;

- With increasing temperatures, the saturation capacity increases, indicating a better accessibility to the adsorption centers on the surface of the precursor/hybrid microparticles;

- The Langmuir constant values increase with increasing temperatures, thus showing a higher metronidazole adsorption efficiency at higher temperatures;

- The highest value of KL was obtained for the ATHA microparticles;

- The values of the constant 1/nF are in the range between 0 and 1, which would indicate that the Freundlich isotherm is favorable for metronidazole adsorption on precursor/hybrid microparticles;

- The values of E are in the range of 3.47–6.97 kJ/mol, indicating that the adsorption process of metronidazole on both the precursor and hybrid microparticles is of a physical nature;

- The values of the exponents nS and nK are very close to unity, which provides a further argument that the adsorption process of metronidazole on precursor/hybrid microparticles is better suited to the Langmuir model than to the Freundlich model;

- The value of the Khan constant, bK, increases with increasing temperatures and has the highest values when using the ATHA hybrid microparticles;

- The values close to unity for the correlation coefficient R2 that are associated with low values of the χ2 test indicate that the Langmuir, Dubinin–Radushkevich, Sips and Khan isotherms apply quite well to the experimental data obtained for metronidazole adsorption on precursor/hybrid microparticles;

- Lower values of R2 and higher values of χ2 obtained from the application of the Freundlich isotherm indicate that this isotherm does not describe the experimental data well.

3.5.2. Kinetic Studies

3.5.3. Thermodynamic Studies

- ∆H values < 40 kJ·mol−1 indicate that the interactions between precursor/hybrid microparticles and metronidazole are physical in nature.

- The positive enthalpy value, ∆H, demonstrates that the adsorption process studied is endothermic.

- The negative values of ∆G indicate that the adsorption processes of metronidazole on the precursor/hybrid microparticles are spontaneous and as the temperatures increase, the negative value of the parameter increases in absolute value, which demonstrates that the adsorption of the drug is favorable at higher temperatures.

- The positive values of entropy, ΔS, suggest the affinity of precursor/hybrid microparticles for metronidazole, and this affinity increases with increasing temperatures.

3.5.4. Release Studies

- Higuchi model [41]:

- Korsmeyer–Peppas model [27]:

- Baker–Lansdale model [42]:

- In the case of precursor microparticles, the value of n < 0.43 indicates that the release mechanism of metronidazole is a Fick-type diffusion mechanism;

- In the case of hybrid microparticles, the value of n is in the range of 0.57–0.63, indicating that the release mechanism of metronidazole is a complex mechanism, controlled by both diffusion and swelling processes characteristic of an anomalous or non-Fickian diffusion;

- The values of the n parameter are less than 0.85, leading to the conclusion that the microparticles swelled but did not undergo any disintegration or erosion.

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ficai, D.; Sandulescu, M.; Ficai, A.; Andronescu, E.; Yetmez, M.; Agrali, O.B.; Elemek, E.; Gunduz, O.; Sahin, Y.M.; Oktar, F.N. Drug Delivery Systems for Dental Applications. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kina, J.R.; Suzuki, T.Y.U.; Kina, E.F.U.; Kina, J.; Kina, M. Non-Inflammatory Destructive Periodontal Disease. Open Dent. J. 2016, 10, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sopi, M.; Kocani, F.; Bardhoshi, M.; Meqa, K. Clinical and Biochemical Evaluation of the Effect of Diode Laser Treatment Compared to the Non-surgical and Surgical Treatment of Periodontal Diseases. Open Dent. J. 2020, 14, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, G.K.; Oliveira, W.P. Manufacturing Drug Loaded Chitosan Microspheres by Spray Drying: Development, Characterization and Potential Use in Dentristry. Dry. Technol. 2007, 25, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.J.; Havaldar, V.D.; Ghorpade, V.S.; Mali, K.K.; Gailwad, V.K.; Kumbhar, D.M. Development and Evaluation of In-Situ Gel Containing Ornidazole LoadedMicrospheres for Treatment of Periodontitis. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 6, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scholz, M.; Reske, T.; Bohmer, F.; Hornung, A.; Grabow, N.; Lang, H. In vitro chlorhexidine release from alginate based microbeads for periodontal therapy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185562. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; Cui, X.; Hou, J.; Yu, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Tong, L. Hyaluronic Acid Modified Nanostructured Lipid Carrier for Targeting Delivery of Kaempferol to NSCLC: Preparation, Optimization, Characterization and Performance Evaluation In Vitro. Molecules 2022, 27, 4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghost, S.; Dutta, S.; Sarkar, A.; Kundu, M.; Sil, P.C. Targeted delivery of curcumin in breast cancer cells via hyaluronic acid modified mesoporous silica nanoparticle to enhance anticancer efficiency. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 197, 111404. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khateeb, R.; Olszewska-Czyz, I. Biological molecules in dental applications: Hyaluronic acid as a companion biomaterial for diverse dental applications. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, D.C.; Ocampo, B.R.Y.; Chirino, C.A.E. Use of hyaluronic acid as an alternative for reconstruction of interdental papilla. Rev. Odontol. Mex. 2017, 21, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Peng, X.; Zhou, X.; Zou, J.; Chen, L. Emerging Applications of Drug Delivery Systems in Oral Infectious Diseases Prevention and Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joshi, D.; Garg, T.; Goyal, A.K.; Rath, G. Advanced drug delivery approaches against periodontitis. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, S.; Lungan, M.A.; Gugoasa, I.; Drobota, M.; Popa, M.; Mihai, M.; Racovita, S. Design of Porous Microparticles Based on Chitosan and Methacrylic Monomers. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 9331–9338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigu, T.A.; Vasiliu, S.; Racovita, S.; Lionte, C.; Sunel, V.; Popa, M.; Cheptea, C. Adsorption and release studies of new cephalosporin from chitosan-g-poly(glycidyl methacrylate) microparticles. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 82, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, S.; Lungan, M.A.; Racovita, S.; Popa, M. Pourous microparticles based on methacrylic copolymers and gellan as drug delivery systems. Polym. Int. 2020, 69, 1066–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, M.; Moffa, A.; Vella, P.; Sabatino, L.; Capuano, F.; Salvinelli, B.; Lopez, M.A.; Carinci, F.; Salvinelli, F. Hyaluronic acid: Pespectives in dentistry. A systematic review. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2016, 29, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, P.; Kamal, P. Hyaluronic acid: A boon in periodontal therapy. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 5, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barde, M.; Adhikari, S.; Via, B.K.; Auad, M.L. Synthesis and characterization of epoxy resin from fast pyrolysis bio-oil. Green Mater. 2018, 6, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lungan, M.A.; Popa, M.; Racovita, S.; Hitruc, G.; Doroftei, F.; Desbrieres, J.; Vasiliu, S. Surface characterization and drug release from porous microparticles based on methacrylic monomers and xanthan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 125, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, C.D.; Vasiliu, S. Crosslinking polymerization of polyfunctional monomers by free radical mechanism. Polimery 2010, 55, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, E.P.; Mintova, S. Nanoporous materials with enhanced hydrophilicity and high water sorption capacity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 114, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanovici, E.; Segal, E. New formal relationship to describe the kinetics of crystallization. Thermochim. Acta 1990, 171, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, E.C.T.; Dumont, M.R.; Martins, P.S.; Drumond, R.M.; Martins da Cruz, M.P.; Vieira, V.F. Investigation of the effects of skewness Rsk and Kurtosis Rku on tribological behavior in a pin-on-disc test of surfaces machined by conventional milling and turning processes. Mater. Res. 2021, 24, e20200435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcu Puscas, T.; Signorini, M.; Molinari, A.; Straffelini, G. Image analysis investigation of the effect of the process variables on the porosity of sintered chromium steels. Mater. Charact. 2003, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauro, S.A.; Vishalakshi, B. Amphoteric gellan gum-based terpolymer-montmorillonite composite: Synthesis, swelling and dye adsorption studies. Int. J. Ind. Chem. 2017, 8, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atta, S.; Khaliq, S.; Islam, A.; Javeria, I.; Jamil, T.; Athar, M.M.; Shafiq, M.I.; Gaffar, A. Injectable biopolymer based hydrogels fordrug delivery applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 80, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsmeyer, R.W.; Gurny, R.; Doelker, E.; Buri, P.; Peppas, N.A. Mechanisms of solute release from porous hydrophilic polymers. Int. J. Pharm. 1983, 15, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freundlich, H.M.F. Over the adsorption in solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1906, 57, 385–470. [Google Scholar]

- Dubinin, M.M.; Zaverina, E.D.; Radushkevich, L.V. Sorption and structure of active carbons. I. Adsorption of organic vapors. Zhurnal Fizicheskoi Khimii 1947, 21, 1351–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Sips, R. On structure of a catalyst surface. J. Chem. Phy. 1948, 16, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Ataullah, R.; Al-Haddad, A. Equilibrium adsorption studies of some aromatic polluants from dilute aqueous solutions on active carbon at different temperature. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 194, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S.; Porter, J.F.; McKay, G. Equilibrium Isotherm Studies for the Sorption of Divalent Metal Ions onto Peat: Copper, Nickel and Lead Single Component Systems. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2002, 141, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, S. About the theory of so-called adsorption of soluble substance. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar 1898, 24, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. The kinetics of sorption of basic dyes from aqueous solutions by Sphagnum moss peat. Can.J. Chem. Eng. 1998, 76, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, B.H.; Tan, I.A.W.; Ahmad, A.L. Adsorption isotherm, kinetic modeling and mechanism of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol on count husk- based activated carbon. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 144, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarici-Ozdemir, C.; Onal, Y. Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic adsorption of the environmental pollutant tannic acid onto activated carbon. Desalination 2010, 251, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriquez, A.; Garcia, J.; Ovejero, G.; Mestanza, M. Adsorption of anionic and cationic dyes on activated carbon from aqueous solutions: Equilibrium and kinetics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefne, J.A.; Mekhemer, W.K.; Alandis, N.M.; Aldayel, O.A.; Alajyan, T. Kinetic and thermodynamic study of the adsorption of Pb (II) from aqueous solution to the naturel and treated bentonite. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2008, 3, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Zhuang, Y.Y.; Wang, Z.H.; Qui, M.Q. Adsorption of water-soluble dyes onto modified resin. Chemosphere 2004, 54, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, T. Diffusional models useful in biopharmaceutics drug release rate processes. J. Pharm. Sci. 1967, 56, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Sousa Lobo, J.M. Modeling and comparison of dissolution profiles. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 13, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadke, K.V.; Manjeshwar, L.S.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Microspheres of Gelatin and Poly(ethylene glycol) Coated with Ethyl Cellulose for Controlled Release of Metronidazole. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 6575–6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupancic, S.; Potrc, T.; Baumgartner, S.; Kocbek, P.; Kristl, J. Formulation and evaluation of chitosan/polyethylene oxide nanofibers loaded with metronidazole for local infections. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 95, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Code | GMA (% mol) | HEMA (% mol) | EGDMA (% mol) | DEGDMA (% mol) | TEGDMA (% mol) | Porogenic Agent | Dilution | Reaction Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | 70 | 20 | 10 | - | - | butyl acetate | 0.6 | 93 |

| AD | 70 | 20 | - | 10 | - | butyl acetate | 0.6 | 90 |

| AT | 70 | 20 | - | - | 10 | butyl acetate | 0.6 | 96 |

| AE | AEHA | AD | ADHA | AT | ATHA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dm (μm) | 124 | 135 | 165 | 173 | 184 | 194 |

| Sample Code | Decomposition Temperature | Residual Mass (%) | Ea (kJ·mol−1) | n | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti (°C) | Tm (°C) | Tf (°C) | |||||

| AE | 180 | 240 | 260 | 5.181 | 121 | 1.7 | 0.992 |

| 270 | 332 | 375 | 179 | 1.8 | 0.992 | ||

| 380 | 411 | 430 | 327 | 1.3 | 0.998 | ||

| AD | 188 | 209 | 222 | 1.57 | 149 | 1.7 | 0.996 |

| 249 | 321 | 349 | 171 | 1.8 | 0.994 | ||

| 349 | 417 | 439 | 223 | 1.8 | 0.994 | ||

| AT | 142 | 150 | 154 | 22.88 | 114 | 1.9 | 0.996 |

| 212 | 242 | 308 | 173 | 1.8 | 0.992 | ||

| 381 | 410 | 442 | 192 | 1.7 | 0.993 | ||

| AEHA | 180 | 231 | 240 | 14.68 | 133 | 1.4 | 0.991 |

| 280 | 341 | 360 | 194 | 1.7 | 0.992 | ||

| 380 | 416 | 460 | 425 | 2.6 | 0.994 | ||

| ADHA | 185 | 199 | 252 | 1.38 | 159 | 1.7 | 0.993 |

| 252 | 291 | 342 | 174 | 1.9 | 0.994 | ||

| 342 | 411 | 432 | 256 | 1.7 | 0.994 | ||

| ATHA | 72 | 94 | 115 | 36.30 | 87 | 1.7 | 0.997 |

| 213 | 253 | 273 | 239 | 1.8 | 0.996 | ||

| 292 | 299 | 321 | 323 | 1.8 | 0.997 | ||

| 361 | 407 | 434 | 476 | 1.8 | 0.996 | ||

| HA | 65 | 102 | 135 | 34.82 | 62 | 1.4 | 0.993 |

| 225 | 263 | 309 | 127 | 1.7 | 0.997 | ||

| 309 | 411 | 510 | 310 | 1.9 | 0.997 | ||

| Sample Code | Epoxy Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | Experimental | |||

| mmol·g−1 | % | mmol·g−1 | % | |

| AE | 4.80 | 20.71 | 2.82 | 12.17 |

| AD | 4.67 | 20.10 | 2.55 | 10.98 |

| AT | 4.54 | 19.52 | 3.22 | 13.86 |

| AEHA | 1.01 | 4.32 | ||

| ADHA | 1.56 | 6.71 | ||

| ATHA | 0.30 | 1.30 | ||

| Sample Code | Sa (nm) | Sq (nm) | Ssk | Sku | dmed (nm) | fshape | felongation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | 124.2 | 131.3 | −0.686 | 0.310 | 314 | 0.363 | 0.485 |

| AD | 143.3 | 156.1 | −0.423 | 0.486 | 369 | 0.391 | 0.426 |

| AT | 156.8 | 172.5 | −0.143 | 0.532 | 265 | 0.426 | 0.375 |

| AEHA | 95.4 | 110.2 | −0.514 | 0.195 | 238 | 0.174 | 0.228 |

| ADHA | 112.9 | 129.9 | −0.365 | 0.371 | 280 | 0.248 | 0.269 |

| ATHA | 126.6 | 143.7 | −0.089 | 0.498 | 176 | 0.323 | 0.280 |

| Sample Code | VP (mL·g−1) | P (%) | Ssp (m2·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AE | 0.7073 | 45 | 78 |

| AD | 0.5076 | 37 | 54 |

| AT | 0.9363 | 52 | 92 |

| AEHA | 0.6004 | 41 | 120 |

| ADHA | 0.4461 | 34 | 86 |

| ATHA | 0.7668 | 47 | 160 |

| Sample Code | Second-Order Model | Korsmeyer–Peppas Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexp (g·g−1) | KS (g·g−1) | Seq (g·g−1) | R2 | K | n | R2 | |

| pH = 1.2 | |||||||

| AE | 1.86 | 0.0033 | 2.07 | 0.997 | 0.282 | 0.172 | 0.999 |

| AD | 1.58 | 0.0026 | 1.73 | 0.998 | 0.212 | 0.164 | 0.998 |

| AT | 2.51 | 0.0045 | 2.80 | 0.997 | 0.315 | 0.225 | 0.998 |

| AEHA | 2.73 | 0.0035 | 2.93 | 0.997 | 0.302 | 0.145 | 0.998 |

| ADHA | 2.46 | 0.0030 | 2.61 | 0.997 | 0.216 | 0.141 | 0.999 |

| ATHA | 3.45 | 0.0050 | 3.69 | 0.997 | 0.325 | 0.239 | 0.999 |

| pH = 5.5 | |||||||

| AE | 1.92 | 0.0028 | 2.09 | 0.997 | 0.234 | 0.200 | 0.997 |

| AD | 1.64 | 0.0025 | 1.77 | 0.997 | 0.205 | 0.195 | 0.999 |

| AT | 2.60 | 0.0030 | 2.84 | 0.998 | 0.266 | 0.237 | 0.998 |

| AEHA | 3.12 | 0.0039 | 3.35 | 0.997 | 0.248 | 0.188 | 0.997 |

| ADHA | 3.08 | 0.0030 | 2.86 | 0.997 | 0.209 | 0.174 | 0.997 |

| ATHA | 3.93 | 0.0054 | 4.19 | 0.998 | 0.294 | 0.242 | 0.998 |

| Isotherm Model | Parameter | AE | AD | AT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | ||

| Langmuir | qm (mg·g−1) | 72.93 | 94.66 | 112.25 | 55.56 | 66.23 | 92.22 | 84.89 | 103.02 | 128.43 |

| KL (L·g−1) | 5.24 | 5.98 | 6.79 | 4.07 | 4.64 | 5.17 | 6.31 | 7.63 | 9.24 | |

| R2 | 0.997 | 0.996 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.997 | 0.996 | 0.995 | 0.998 | 0.999 | |

| χ2 | 0.143 | 0.566 | 0.163 | 0.025 | 0.218 | 0.356 | 0.891 | 0.360 | 0.161 | |

| Freundlich | KF (L·g−1) | 60.70 | 80.25 | 101.08 | 43.16 | 62.32 | 87.65 | 70.28 | 95.68 | 122.57 |

| 1/nF | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.20 | |

| R2 | 0.949 | 0.947 | 0.952 | 0.972 | 0.969 | 0.968 | 0.941 | 0.956 | 0.941 | |

| χ2 | 52.148 | 83.909 | 64.88 | 14.212 | 25.898 | 36.104 | 79.554 | 101.484 | 107.284 | |

| Dubinin-Radushkevich | qm (mg·g−1) | 65.39 | 85.82 | 106.01 | 47.16 | 66.23 | 92.28 | 75.73 | 103.02 | 128.43 |

| E (kJ·mol−1) | 3.80 | 4.06 | 4.86 | 3.47 | 3.91 | 4.67 | 3.86 | 4.12 | 4.97 | |

| R2 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.996 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.999 | |

| χ2 | 0.293 | 0.285 | 0.252 | 0.257 | 0.186 | 0.162 | 0.335 | 0.064 | 0.061 | |

| Sips | qm (mg·g−1) | 67.14 | 87.98 | 108.98 | 55.18 | 72.91 | 100.08 | 75.82 | 108.28 | 129.30 |

| KS (L·mg−1) | 5.31 | 6.03 | 7.17 | 4.25 | 4.88 | 5.25 | 7.30 | 8.94 | 10.30 | |

| nS | 1.15 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 1.15 | 1.16 | 1.14 | |

| R2 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.997 | 0.999 | 0.997 | 0.998 | |

| χ2 | 0.393 | 0.209 | 0.094 | 0.214 | 0.275 | 0.239 | 0.250 | 0.619 | 0.154 | |

| Khan | qm (mg·g−1) | 85.51 | 100.91 | 120.95 | 57.11 | 71.42 | 95.51 | 94.88 | 113.90 | 144.25 |

| bK | 2.11 | 3.17 | 4.38 | 1.05 | 2.46 | 3.41 | 2.66 | 3.03 | 5.88 | |

| nK | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.08 | |

| R2 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.997 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.997 | |

| χ2 | 0.143 | 0.097 | 0.168 | 0.177 | 0.043 | 0.125 | 0.037 | 0.142 | 0.166 | |

| Isotherm Model | Parameter | AEHA | ADHA | ATHA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | ||

| Langmuir | qm (mg·g−1) | 227.75 | 237.60 | 250.99 | 221.75 | 230.22 | 238.39 | 233.79 | 251.62 | 262.05 |

| KL (L·g−1) | 21.20 | 24.71 | 29.17 | 12.98 | 14.68 | 16.74 | 23.08 | 28.32 | 34.58 | |

| R2 | 0.995 | 0.996 | 0.998 | 0.995 | 0.996 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.998 | |

| χ2 | 0.721 | 0.579 | 0.369 | 0.608 | 0.256 | 0.149 | 0.142 | 0.134 | 0.156 | |

| Freundlich | KF (L·g−1) | 216.32 | 225.40 | 237.72 | 209.33 | 218.16 | 225.80 | 223.80 | 240.63 | 251.10 |

| 1/nF | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | |

| R2 | 0.934 | 0.927 | 0.923 | 0.923 | 0.929 | 0.930 | 0.950 | 0.920 | 0.947 | |

| χ2 | 153.564 | 181.197 | 228.701 | 180.312 | 166.542 | 190.317 | 92.568 | 171.073 | 123.686 | |

| Dubinin-Radushkevich | qm (mg·g−1) | 282.36 | 300.36 | 312.01 | 256.49 | 279.21 | 295.56 | 296.41 | 311.17 | 320.38 |

| E (kJ·mol−1) | 6.24 | 6.31 | 6.38 | 6.00 | 6.27 | 6.33 | 6.71 | 6.77 | 6.97 | |

| R2 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.997 | 0.998 | |

| χ2 | 0.087 | 0.603 | 0.207 | 0.066 | 0.289 | 0.125 | 0.212 | 0.209 | 0.057 | |

| Sips | qm (mg·g−1) | 222.61 | 230.17 | 242.42 | 213.49 | 223.37 | 232.16 | 233.96 | 244.28 | 260.19 |

| KS (L·mg−1) | 22.67 | 26.47 | 30.10 | 12.09 | 14.23 | 17.39 | 23.75 | 29.90 | 35.34 | |

| nS | 1.14 | 1.22 | 1.15 | 1.17 | 1.19 | 1.14 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 1.07 | |

| R2 | 0.997 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.997 | |

| χ2 | 0.348 | 0.130 | 0.267 | 0.072 | 0.182 | 0.391 | 0.254 | 0.186 | 0.172 | |

| Khan | qm (mg·g−1) | 233.19 | 240.25 | 254.73 | 227.07 | 232.27 | 241.19 | 241.44 | 257.32 | 269.98 |

| bK | 2.53 | 3.86 | 4.92 | 1.76 | 2.90 | 3.84 | 3.79 | 4.52 | 6.95 | |

| nK | 1.03 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.01 | |

| R2 | 0.997 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.997 | |

| χ2 | 0.323 | 0.136 | 0.191 | 0.137 | 0.074 | 0.185 | 0.126 | 0.153 | 0.167 | |

| AE | AD | AT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | |

| qe,exp (mg·g−1) | 59.00 | 78.00 | 99.00 | 42.00 | 61.00 | 86.00 | 68.00 | 93.00 | 120.00 |

| Lagergren model | |||||||||

| qe,calc (mg·g−1) | 57.97 | 76.99 | 97.92 | 41.78 | 60.44 | 84.60 | 67.28 | 91.68 | 118.53 |

| k1 × 102 (min−1) | 0.953 | 0.989 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 1.13 | 1.23 |

| R2 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.999 |

| χ2 | 1.228 | 1.317 | 1.257 | 1.248 | 1.209 | 1.228 | 0.656 | 0.311 | 0.431 |

| Ho model | |||||||||

| qe,calc (mg·g−1) | 66.53 | 89.09 | 113.94 | 48.65 | 72.01 | 98.64 | 76.47 | 106.10 | 139.07 |

| k2 × 105 (g·mg−1·min−1) | 10.88 | 12.01 | 22.68 | 9.54 | 10.84 | 19.51 | 7.16 | 13.01 | 18.92 |

| R2 | 0.991 | 0.995 | 0.994 | 0.989 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.987 | 0.995 | 0.995 |

| χ2 | 4.629 | 4.128 | 4.554 | 9.230 | 4.201 | 6.215 | 9.396 | 6.081 | 9.206 |

| Elovich model | |||||||||

| α (mg·g−1·min−1) | 1.37 | 1.62 | 1.93 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 1.62 | 1.83 | 1.93 | 2.11 |

| β (g·mg−1) | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| R2 | 0.964 | 0.975 | 0.974 | 0.963 | 0.981 | 0.977 | 0.953 | 0.975 | 0.979 |

| χ2 | 59.661 | 24.428 | 40.029 | 50.971 | 11.864 | 27.106 | 34.217 | 33.678 | 46.254 |

| Weber–Morris intraparticle diffusion model | |||||||||

| kid (mg·g−1·min-0.5) | 1.10 | 1.18 | 1.27 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 1.42 | 1.49 | 1.65 |

| Ci2 | 25.10 | 36.30 | 44.37 | 22.62 | 33.21 | 40.90 | 29.03 | 39.94 | 48.96 |

| R2 | 0.994 | 0.995 | 0.996 | 0.993 | 0.994 | 0.994 | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.996 |

| AEHA | ADHA | ATHA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | |

| qe,exp (mg·g−1) | 213.00 | 222.00 | 234.00 | 206.00 | 215.00 | 221.00 | 221.00 | 237.00 | 248.00 |

| Lagergren model | |||||||||

| qe,calc (mg·g−1) | 212.67 | 221.74 | 230.96 | 207.12 | 213.36 | 220.58 | 218.68 | 234.06 | 244.72 |

| k1 × 102 (min−1) | 1.16 | 1.28 | 1.34 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 1.10 | 1.35 | 1.38 | 1.43 |

| R2 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.998 | 0.998 |

| χ2 | 1.057 | 1.287 | 1.268 | 1.146 | 1.131 | 1.164 | 1.391 | 1.379 | 1.354 |

| Ho model | |||||||||

| qe,calc (mg·g−1) | 253.13 | 256.88 | 262.92 | 246.05 | 251.24 | 253.98 | 249.82 | 266.95 | 276.84 |

| k2 × 105 (g·mg−1·min−1) | 4.11 | 5.12 | 6.16 | 4.09 | 4.88 | 5.82 | 5.89 | 6.21 | 6.89 |

| R2 | 0.990 | 0.989 | 0.990 | 0.991 | 0.988 | 0.988 | 0.987 | 0.993 | 0.993 |

| χ2 | 76.336 | 89.173 | 79.617 | 62.628 | 92.856 | 88.002 | 93.383 | 63.624 | 59.873 |

| Elovich model | |||||||||

| α (mg·g−1·min−1) | 3.77 | 5.22 | 7.27 | 3.55 | 4.61 | 6.14 | 6.44 | 7.12 | 8.58 |

| β (g·mg−1) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| R2 | 0.967 | 0.960 | 0.958 | 0.971 | 0.959 | 0.957 | 0.954 | 0.962 | 0.964 |

| χ2 | 247.758 | 325.663 | 347.937 | 212.145 | 312.975 | 338.627 | 352.700 | 319.802 | 331.668 |

| Weber-Morris intraparticle diffusion model | |||||||||

| kid (mg·g−1·min−0.5) | 1.36 | 1.41 | 1.56 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.86 | 1.63 | 1.73 | 1.81 |

| Ci2 | 34.60 | 49.61 | 52.27 | 31.29 | 46.44 | 51.45 | 40.37 | 52.30 | 57.03 |

| R2 | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.994 | 0.994 | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.996 |

| Sample Code | ΔH (kJ·mol−1) | ΔS (J·mol−1) | ΔG (kJ·mol−1) | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | ||||

| AE | 19.81 | 80.28 | −4.10 | −4.50 | −4.90 | 0.999 |

| AD | 18.36 | 73.31 | −3.48 | −3.85 | −4.21 | 0.997 |

| AT | 29.17 | 113.21 | −4.56 | −5.12 | −5.69 | 0.999 |

| AEHA | 24.34 | 107.07 | −7.56 | −8.09 | −8.63 | 0.997 |

| ADHA | 19.40 | 86.42 | −6.34 | −6.77 | −7.21 | 0.998 |

| ATHA | 30.82 | 129.53 | −7.77 | −8.42 | −9.07 | 0.999 |

| Sample Code | Higuchi Model | Korsmeyer–Peppas Model | Baker–Lansdale Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kH (min-0.5) | R2 | kr (min-n) | n | R2 | KBL | R2 | |

| AE | 4.101 | 0.991 | 0.082 | 0.40 | 0.998 | 0.047 | 0.990 |

| AD | 3.879 | 0.990 | 0.075 | 0.35 | 0.997 | 0.040 | 0.991 |

| AT | 4.258 | 0.994 | 0.087 | 0.42 | 0.998 | 0.051 | 0.989 |

| AEHA | 3.052 | 0.989 | 0.062 | 0.61 | 0.997 | 0.041 | 0.989 |

| ADHA | 2.736 | 0.990 | 0.037 | 0.57 | 0.998 | 0.034 | 0.988 |

| ATHA | 3.208 | 0.989 | 0.075 | 0.63 | 0.999 | 0.046 | 0.989 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gugoasa, A.I.; Racovita, S.; Vasiliu, S.; Popa, M. Grafted Microparticles Based on Glycidyl Methacrylate, Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate and Sodium Hyaluronate: Synthesis, Characterization, Adsorption and Release Studies of Metronidazole. Polymers 2022, 14, 4151. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14194151

Gugoasa AI, Racovita S, Vasiliu S, Popa M. Grafted Microparticles Based on Glycidyl Methacrylate, Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate and Sodium Hyaluronate: Synthesis, Characterization, Adsorption and Release Studies of Metronidazole. Polymers. 2022; 14(19):4151. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14194151

Chicago/Turabian StyleGugoasa, Aurica Ionela, Stefania Racovita, Silvia Vasiliu, and Marcel Popa. 2022. "Grafted Microparticles Based on Glycidyl Methacrylate, Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate and Sodium Hyaluronate: Synthesis, Characterization, Adsorption and Release Studies of Metronidazole" Polymers 14, no. 19: 4151. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14194151

APA StyleGugoasa, A. I., Racovita, S., Vasiliu, S., & Popa, M. (2022). Grafted Microparticles Based on Glycidyl Methacrylate, Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate and Sodium Hyaluronate: Synthesis, Characterization, Adsorption and Release Studies of Metronidazole. Polymers, 14(19), 4151. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14194151