Sites and Indicators of MAR as a Successful Tool to Mitigate Climate Change Effects in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

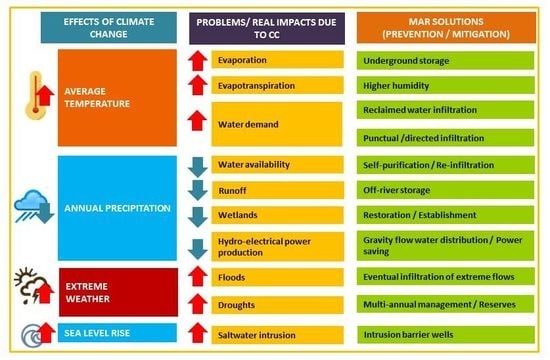

- Examples of technological solutions to palliate rising temperatures (Section 3.1).

- Examples of technological solutions to palliate decreasing annual precipitation rates (Section 3.2).

- Examples of technological solutions to manage extreme phenomena (Section 3.3).

- Examples of technological solutions to reduce the rising of the sea level and saline water intrusion (Section 3.4).

3.1. Examples of Technological Solutions to Palliate Rising Temperatures

3.1.1. Underground Water Storage. Canal del Guadiana, Castilla-La Mancha (1 in Figure 2)

3.1.2. Temperature Reduction. Parc Bit, Palma de Mallorca, I. Balears (2)

3.1.3. Increase in Soil Humidity. Gomezserracín, Castilla y León (3)

3.1.4. Reclaimed Water Infiltration. Alcazarén, Castilla y León (4)

3.1.5. Punctual Infiltration. Canal de Isabel II, Madrid (5)

3.2. Examples of Technological Solutions to Palliate Decreasing Annual Precipitation Rates

3.2.1. Self-Purification by Natural Biofilters and Nature Based Solutions. Santiuste, Castilla y León (6)

3.2.2. Wetlands Restoration. Santiuste, Castilla y León (6)

3.2.3. Gravity Flow Water Distribution. El Carracillo, Castilla y León (7)

3.2.4. Energy Efficiency Increase through Managed Aquifer Recharge (El Carracillo, Castilla y León)

3.3. Examples of Technological Solutions to Manage Extreme Phenomena

3.3.1. Infiltration of Extreme Flows. Lliria, Valencia (8)

3.3.2. Forested watersheds. Neila, Castilla y León (9)

3.3.3. Multi-Annual Management. Santiuste Basin (CyL) (6)

3.4. Examples of Technological Solutions to Reduce Sea Level Rise

Positive Hydraulic Barrier. El Prat de Llobregat, Barcelona (10)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AW | Artificial Wetlands |

| MAR | Managed Aquifer Recharge |

| CC | Climate Change |

| NBS | Nature Based Solutions |

| SUDS | Sustainable Drainage Urban Systems |

| UHI | Urban Heat Island |

| WWTP | Waste Water Treatment Plant |

| MSCA | Marie Sklodowska Curie Action |

References

- Taylor, R.G.; Scanlon, B.; Döll, P.; Rodell, M.; Van Beek, R.; Wada, Y.; Longuevergne, L.; Leblanc, M.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Edmunds, M.; et al. Ground water and climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimikou, M.A.; Baltas, E.; Varanou, E.; Pantazis, K. Regional impacts of climate change on water resources quantity and quality indicators. J. Hydrol. 2000, 234, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EU Water Framework Directive—Integrated River Basin Management for Europe. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/water-framework/index_en.html (accessed on 9 March 2019).

- Pholkern, K.; Saraphirom, P.; Srisuk, K. Potential impact of climate change on groundwater resources in the Central Huai Luang Basin, Northeast Thailand. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 1518–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Menéndez, O.; Morell, I.; Ballesteros, B.J.; Renau-Prunonosa, A.; Renau-Llorens, A.; Esteller, M.V. Spatial characterization of the seawater upconing process in a coastal Mediterranean aquifer (Plana de Castellón, Spain): Evolution and controls. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrocicco, M.; Busico, G.; Colombani, N.; Vigliotti, M.; Ruberti, D. Modelling Actual and Future Seawater Intrusion in the Variconi Coastal Wetland (Italy) Due to Climate and Landscape Changes. Water 2019, 11, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.; Tyson, G. Climate-Change Adaptation & Groundwater, IAH Strategic Overview Series. 2019. Available online: https://iah.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/IAH_Climate-ChangeAdaptationGdwtr.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- IPCC. Resumen para responsables de políticas. In Cambio Climático 2013: Bases Físicas. Contribución del Grupo de trabajo I al Quinto Informe de Evaluación del Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático; Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex y, V., Midgley, P.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Valores Climatológicos Extremos Medidos en Siguientes Periodos. Temperatura: 955 a 2010. Temperatura Máxima Absoluta (°C). Available online: http://www.castillalamancha.es/sites/default/files/clima_valores_extremos.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- DINAMAR. La Gestión de la Recarga Artificial de Acuíferos en el Marco del Desarrollo Sostenible. Desarrollo Tecnológico. Coord. Enrique Fernández-Escalante. Serie Hidrogeología Hoy, No 6. Método Gráfico. 2010. Available online: http://goo.gl/6lp4m (accessed on 2 June 2019).

- Zhou, Q. A Review of Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems Considering the Climate Change and Urbanization Impacts. Water 2014, 6, 976–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIAE. The Comprehensive Management of Rainwater in Built-up Areas; Legal Deposit M-9957-2015; Tragsa Group: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MARSOL; Fernández Escalante, E.; Calero Gil, R.; Villanueva Lago, M.; San Sebastián Sauto, J.; Martínez Tejero, O.; Valiente Blázquez, J.A. Appropriate MAR Methodology and Tested Know-How for the General Rural Development; MARSOL deliverable 5-3; MARSOL: Darmstadt, Germany, 2016; Available online: http://marsol.eu/35-0-Results.html (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- IMTA. Manejo de la Recarga de Acuíferos: Un enfoque hacia Latinoamérica; IMTA: Progreso, México, 2017; p. 977. Available online: https://www.imta.gob.mx/biblioteca/libros_html/manejo-recarga-acuiferos-ehl.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- López-Camacho, B.; Iglesias, J.A.; Muñoz, A.; Sánchez, E.; Cabrera, E. Gestión sostenible de los recursos hídricos en el sistema de abastecimiento de la Comunidad de Madrid. Equip. Serv. Munic. 2007, 133, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, B.C.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Wu, S.; Palutikof, J.P. (Eds.) El Cambio Climático y el Agua. In Documento Técnico del Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos Sobre el Cambio Climático; Secretaría del IPCC: Ginebra, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Escalante, E. 2002–2012, una década de recarga gestionada. In Acuífero de la Cubeta de Santiuste (Castilla y León); Tragsa, Ed.; Tragsa Group: Madrid, Spain, 2014; ISBN 84-616-8910-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Escalante, E. Mecanismos de “detención-infiltración” para la recarga intencionada de los acuíferos como estrategia de adaptación al cambio climático. In Revista IDiAgua, Número 1, Junio de 2018 Fenómenos Extremos y Cambio Climático; Plataforma Tecnológica Española del Agua: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- San Sebastián Sauto, J.; Fernández Escalante, E.; González Herrarte, F.D.B. La Recarga Gestionada en Santiuste: 13 Años de Usos y Servicios Múltiples para la Comunidad Rural. Rev. Tierras 2015, 234, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- CETaqua, Centro Tecnológico del Agua. Enhancement of Soil Aquifer Treatment to Improve the Quality of Recharge Water in the Llobregat River Delta Aquifer Life+ ENSAT project 2010–2012 Layman’s Report; CETaqua, Centro Tecnológico del Agua: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Del Barrio, V. The activity seen from the Duero river basin and the RBMP. In Proceedings of the MAR4FARM Training Workshop Presentation, Gomezserracín, Segovia, Spain, 29–30 October 2014; Available online: http://www.dina-mar.es/post/2014/11/17/mar4farm-presentaciones-presentations-available-freely-on-the-internet.aspx (accessed on 15 August 2019).

- MARSOL; Fernández Escalante, E.; Calero Gil, R.; González Herrarte, B.; San Sebastián Sauto, J.; Del Pozo Campos, E. Los Arenales Demonstration Site Characterization. Report on the Los Arenales Pilot Site Improvements; MARSOL deliverable 5-1; MARSOL: Darmstadt, Germany, 2015; Available online: http://marsol.eu/35-0-Results.html (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- IWMI en GRIPP; Escalante, E.F.; San Sebastián Sauto, J. The Alcazarén-Pedrajas MAR scheme in Central Spain. 2018. Available online: https://bit.ly/2LnLXzT (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- Ebi, K.; Lim, B.; Aguilar, I. Scoping and Designing an Adaptation Project in Adaptation Policy Frameworks for Climate Change: Developing Strategies, Policies and Measures; Lim, B., Spanger-Siegfried, E., Eds.; United Nations Development Programme; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; pp. 33–47. ISBN 0 521 61760 X. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, J.; Estrela, T. Regionalisation and identification of droughts in Mediterranean countries of Europe. In Tools for Drought Mitigation in Mediterranean Regions, Water Science and Technology Library Volume 44; Rossi, G., Cancelliere, A., Pereira, L.S., Oweis, T., Shatanawi, M., Zairi, A., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 123–146. ISBN 1-4020-1140-7. [Google Scholar]

| MAR SITE (*) | CC IMPACT | INDICATOR/S |

|---|---|---|

| Guadiana Canal, Castilla-La Mancha (1) | PALLIATE RISING TEMPERATURE | Capability to recharge peak flows: Intermittent underground water storage. Total recharge in 48 supplementary hm3/year |

| Parc Bit Majorca Island (2) | Palliate rising temperature | Lower surface temperature according to thermographic photographs |

| Gomezserracín, Castilla y León (3) | Palliate rising temperature | Increase in soil humidity during MAR cycles |

| Alcazarén, Castilla y León (4) | Strategic water storage/Palliate rising temperature | Increases of 0.4 hm3 per year recharging reclaimed water |

| CYII Madrid (5) | Strategic water storage/Palliate rising temperature | Capability to recharge peak flows: Increases up to 5 hm3 per year by recharging potable water excess |

| Santiuste, Castilla y León (6) | PALLIATE DECREASING PRECIPITATION RATES | Strategic reserve for drought periods +/−12–53% in water physical and chemical parameters |

| Santiuste, Castilla y León (6) | Wetlands Restoration | 5% recharge volume dedicated to alkaline lake restoration |

| El Carracillo, Castilla y León (7) | Gravity flow water distribution | Transport length without pumpage: 40.7 km of pipes and channels by gravity. Supplied irrigated area: 3500 ha |

| El Carracillo, Castilla y León (7) | Energy efficiency through Managed Aquifer Recharge | Saving in terms of kW-h is between 12 and 36% thanks to water level rise |

| Arnachos, Valencia (8) | MANAGE EXTREME CC PHENOMENA | Reduce precipitation peak thank to a high recharge capacity borehole (up to 1000 L/s) |

| Neila, Castilla y León (9) | Forested watersheds | Forest is capable of retaining and channelling 15%–40% of the volume of surface runoff |

| Santiuste, Castilla y León (5) | Multiannual management by means of Off-river storage | 2.62 hm3/year stored out of Voltoya River would allow groundwater extractions for irrigation during 3 years with no rain |

| El Prat de Llobregat, Cataluña (10) | REDUCE SEA LEVEL RISE AND SALINE WATER INTRUSION | Evolution of seawater intrusion by iso-chlorides lines evolution |

| MAR SOLUTIONS | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|

| Underground water storage | Water recharge can help to restore wetlands associated with overexploited aquifers, especially when winter extraordinary flows are used as a recharging source. | Run-off abstraction can change recharge into negative impact, considering downstream ecosystems |

| Temperature reduction | Broad array of possibilities in SDUS, from parking lots to roofs, from rain storage to high evaporation systems | Risk of accidental pollution through run off on contaminated areas |

| Soil humidity increase | Maintenance of micro-flora and fauna in the soil, increase in fertility, low infiltration with small investment and good purification | High soil humidity can facilitate flooding by water table rising or freezing in cold climates. Balance between unsaturated and saturated areas should be searched |

| Reclaimed water infiltration | Decreasing offer of primary sources (rain and run-off) and increasing offer of secondary ones (WWTP, desalination, storm reservoirs). Chance to change a split into a resource | Reclaimed water involves unbalance between recharging water quality and receptor aquifer quality, clogging during infiltration and legal limits to recharge (EIA) or to use (authorization) |

| Punctual infiltration | High potential to manage peak flows in constrained areas with filtering systems and possibility of deep recharge as a safety measure in open aquifers | Decantation processes can get clogged. Forced refill can reduce the availability of extreme flows from unexpected storms |

| Self-purification | Possibility of design according to characteristics of the spillage parameters, combining depth or development of vegetation that allow the development of physical, chemical and biological phenomena depending on draft, type of background, speed of flow, entry of light. Manageable characteristics also to accommodate different types of habitats | The mixture with poor quality waters can affect the infiltrating capacity of the aquifer by either clogging the unsaturated zone or compromising the possibilities and authorizations to use the final mixture. The development of certain vegetation can favour a greater infiltration through the roots or, on the contrary, encourage surface clogging by the formation of bacterial biofilms |

| Restoration | Slow infiltration into areas where sufficient surface is available for infiltration ponds allows temporary wetlands permanence requiring only a fraction of the total rechargeable volume and, at the same time, fulfils relevant ecosystem functions as a refuge for wild fauna and flora | The establishment of free water sheets may limit the use of reclaimed water due to possible health risks |

| Gravity flow water distribution | The greater the knowledge of the aquifer is, the greater is the established systems that take advantage of the hydraulic characteristics of the terrain | Detailed hydrology and geotechnics knowledge play a fundamental role in order to take advantage of the potential distribution of water along the aquifer by simple gravity. Precise studies are essential |

| Savings/Lower emissions | In this context, new lines of action are being considered to improve energy efficiency, such as the replacement of diesel engines by electric motors, the use of alternative energies to reduce pumping costs, such as solar panels, wind energy, and greater use of biomass | The improvement of the economic conditions allowing energy consumption can become a dangerous stimulus for the excessive increase in agricultural demand, thus, it is necessary to establish regulations for general resources management |

| Infiltration of a part of extreme flows | High capacity to manage overfloods and peak flows in reduced spaces with the application of measures that decrease solid load. Ability to redirect flows to deep aquifers to avoid flooding in certain sectors of unconfined aquifers | Overfloods must be previously laminated to be partially infiltrated. The enhanced infiltration in the aquifer might reduce the soil capacity to absorb extreme precipitation by infiltration |

| Forested watersheds | Watersheds erosion control and promotion of forest hydrological restoration thanks to detention/retention devices to form soil and reduce slope. Development of deep soil botanical species with greater terrain stability (the retention of solids allows to increase the useful life of dams) | Water retention in the heading of the basin reduces downstream runoff, enhances soil formation and has a direct effect on associated wetlands |

| Multiannual management | Underground reserves do not require certain precautionary measures such as winter water releases, but might need to divert certain volumes to deep aquifers for exploitation in emergencies | Multi-year management implies a very good organization of uses with a great cohesive spirit among stakeholders. Despite their advantages over dams, they also require precautions against water table excessive rises |

| Intrusion barrier wells | Acceptable use of low-quality sources (high NaCl or NO3 concentration) carefully combined for MAR | Collateral effects of pollutants in the recharged volumes on the aquifer’s potential storage |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Escalante, E.F.; Sauto, J.S.S.; Gil, R.C. Sites and Indicators of MAR as a Successful Tool to Mitigate Climate Change Effects in Spain. Water 2019, 11, 1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11091943

Escalante EF, Sauto JSS, Gil RC. Sites and Indicators of MAR as a Successful Tool to Mitigate Climate Change Effects in Spain. Water. 2019; 11(9):1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11091943

Chicago/Turabian StyleEscalante, Enrique Fernández, Jon San Sebastián Sauto, and Rodrigo Calero Gil. 2019. "Sites and Indicators of MAR as a Successful Tool to Mitigate Climate Change Effects in Spain" Water 11, no. 9: 1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11091943

APA StyleEscalante, E. F., Sauto, J. S. S., & Gil, R. C. (2019). Sites and Indicators of MAR as a Successful Tool to Mitigate Climate Change Effects in Spain. Water, 11(9), 1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11091943