Quantitative XRD Analysis of the Structural Changes of Ba-Exchanged Montmorillonite: Effect of an in Situ Hydrous Perturbation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Sample

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Investigation

2.3.1. XRD Measurements

2.3.2. Relative Humidity Sequences

2.3.3. Semi-Quantitative XRD Investigation

2.3.4. Quantitative XRD Investigation

3. Results and Discussion

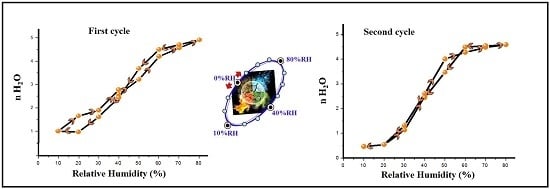

3.1. First Hydration/Dehydration Cycle

3.1.1. Qualitative XRD Analysis

3.1.2. Quantitative XRD Investigation

Evolution of the Hydration Performance

| Process | % RH | d001 (Å) | FWHM (° 2θ) | ξ, Xi | Character |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case of the First Cycle | |||||

| Hydration | 40 (Starting) | 14.94 | 1.55 | 0.97, 3 | I |

| 50 | 16.38 | 1.21 | 0.55, 3 | I | |

| 60 | 16.92 | 0.88 | 0.52, 3 | I | |

| 70 | 17.07 | 0.80 | 0.69, 3 | I | |

| 80 | 17.19 | 0.78 | 0.67, 3 | I | |

| Dehydration | 70 | 17.06 | 0.80 | 0.55, 3 | I |

| 60 | 16.8 | 0.90 | 0.50, 3 | I | |

| 50 | 16.16 | 1.55 | 0.32, 3 | I | |

| 40 | 14.74 | 1.46 | 0.68, 3 | I | |

| 30 | 14.06 | 0.89 | 0.37, 3 | H | |

| 20 | 13.94 | 0.90 | 0.39, 3 | H | |

| 10 | 13.11 | 1.12 | 0.52, 3 | I | |

| Hydration | 20 | 14.01 | 0.96 | 0.51, 3 | I |

| 30 | 14.11 | 0.99 | 0.52, 3 | I | |

| 40 (Return) | 14.89 | 0.63 | 0.37, 3 | H | |

| Case of the Second Cycle | |||||

| Dehydration | 40 (Starting) | 14.96 | 1.32 | 0.52, 3 | I |

| 30 | 13.61 | 0.77 | 0.25, 3 | H | |

| 20 | 12.45 | 0.87 | 0.23, 3 | H | |

| 10 | 12.27 | 0.89 | 0.20, 3 | H | |

| Hydration | 20 | 12.40 | 0.90 | 0.20, 3 | H |

| 30 | 13.43 | 0.78 | 0.24, 3 | H | |

| 40 | 14.79 | 1.34 | 0.66, 3 | I | |

| 50 | 15.74 | 0.94 | 0.35, 3 | H | |

| 60 | 16.13 | 0.71 | 0.22, 3 | H | |

| 70 | 16.45 | 1.30 | 0.70, 3 | I | |

| Dehydration | 80 | 16.80 | 0.90 | 0.55, 3 | I |

| 70 | 16.66 | 0.82 | 0.70, 3 | I | |

| 60 | 16.40 | 0.68 | 0.20, 3 | H | |

| 50 | 16.09 | 0.73 | 0.19, 3 | H | |

| 40 (Return) | 15.50 | 1.55 | 0.59, 3 | I | |

Evolution of the Layers Types in Structure

| Process | % RH | % of MLS | 0W/1W/2W/3W-R0//R1 | N H2O | Z H2O | n Ba | Z Ba | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0W | 0W | 0W | 0W | |||||

| 1W | 1W | 1W | 1W | |||||

| 2W | 2W | 2W | 2W | |||||

| 3W | 3W | 3W | 3W | |||||

| Hydration | 40 | 64 | 0/15/85/0–R0 | - | - | - | - | 8 |

| Start | 36 | 0/65/35/0–R1 | 1 | 10.30 | 0.15 | 10.30 | ||

| 4 | 11.40/14.60 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 50 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 45 | 0/75/25/0–R1 | 2.5 | 10.00 | 0.15 | 10.00 | |||

| 37.40 | 0/45/55/0–R0 | 4 | 11.20/14.70 | 0.15 | 12.00 | 8 | ||

| 17.60 | 0/0/75/25–R0 | 3.6 | 11.50/14.30/16.20 | 0.15 | 14.30 | |||

| 60 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 56 | 0/0/75/25–R1 | 2.5 | 10.20 | 0.15 | 10.20 | |||

| 30 | 0/80/20/0–R1 | 5 | 11.00/14.40 | 0.15 | 12.00 | 9 | ||

| 14 | 0/30/70/0–R1 | 5.4 | 11.50/14.70/16.20 | 0.15 | 14.70 | |||

| 70 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 61.64 | 0/0/70/30–R1 | 2 | 10.20 | 0.15 | 10.20 | |||

| 30.36 | 0/75/25/0–R1 | 5 | 11.20/14.60 | 0.15 | 12.00 | 8 | ||

| 8 | 0/0/15/85–R1 | 6 | 11.50/14.90/16.70 | 0.15 | 14.90 | |||

| 80 | 54 | 0/0/55/45–R0 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 46 | 0/60/40/0–R0 | 2.5 | 10.00 | 0.15 | 10.00 | 7 | ||

| 5.2 | 11.30/14.70 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| 7.5 | 11.30/14.80/16.60 | 0.15 | 14.80 | |||||

| Dehydration | 70 | 51 | 0/0/55/45–R1 | - | - | - | - | |

| 49 | 0/65/35/0–R1 | 2 | 10.20 | 0.15 | 10.20 | 8 | ||

| 5.2 | 11.30/14.70 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| 7.5 | 11.30/14.80/16.60 | 0.15 | 14.80 | |||||

| 60 | 42 | 0/70/30/0–R1 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 40.60 | 0/0/65/35–R1 | 1.5 | 10.50 | 0.15 | 10.50 | 8 | ||

| 17.40 | 0/25/75/0–R0 | 5 | 10.80/14.80 | 0.15 | 12.10 | |||

| 5.4 | 11.50/14.60/16.40 | 0.15 | 14.60 | |||||

| 50 | 76 | 0/60/40/0–R1 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 19 | 0/30/70/0–R1 | 2.5 | 09.80 | 0.15 | 09.80 | 7 | ||

| 5 | 0/0/70/30–R1 | 5 | 10.80/14.80 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||

| 3.6 | 10.20/14.50/16.40 | 0.15 | 14.50 | |||||

| 40 | 87 | 0/55/45/0–R1 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 13 | 0/30/70/0–R1 | 1 | 10.00 | 0.15 | 10.00 | 8 | ||

| 4 | 11.20/14.70 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 30 | 55 | 0/80/20/0–R0 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 45 | 0/55/45/0–R0 | 1 | 10.70 | 0.15 | 10.70 | 10 | ||

| 3 | 11.00/13.80 | 0.15 | 12.00 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 20 | 77 | 0/85/15/0–R0 | - | - | 0.15 | 8.90 | ||

| 23 | 45/55/0/0–R1 | 1 | 10.70 | 0.15 | 10.70 | |||

| 2 | 11.50/14.20 | 0.15 | 12.00 | 11 | ||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 10 | 80 | 15/85/0/0–R1 | - | - | 0.15 | 9.00 | ||

| 20 | 0/65/35/0–R0 | 1 | 10.70 | 0.15 | 10.70 | 11 | ||

| 2.4 | 11.00/14.50 | 0.15 | 12.00 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| Hydration | 20 | 72 | 0/65/35/0–R0 | - | - | 0.15 | 8.90 | |

| 28 | 30/70/0/0–R0 | 1 | 10.70 | 0.15 | 10.70 | 10 | ||

| 4 | 11.20/14.80 | 0.15 | 12.00 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 30 | 80 | 0/60/40/0–R0 | - | - | 0.15 | 9.00 | ||

| 20 | 25/75/0/0–R0 | 1 | 10.30 | 0.15 | 10.30 | 10 | ||

| 4 | 11.20/14.80 | 0.15 | 12.00 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 40 | 58 | 0/30/70/0–R1 | - | - | - | - | 7 | |

| 42 | 0/55/45/0–R1 | 1 | 10.50 | 0.15 | 10.50 | |||

| 4 | 11.00–14.60 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| - | - | - |

3.2. The Second Hydration/Dehydration Cycle

3.2.1. Qualitative XRD Investigation

3.2.2. Quantitative XRD Analysis

Progress of the Heterogeneous Hydration in the Structure

| Procedure | % RH | % of MLS | 0W/1W/2W/3W-R0//R1 | n H2O | Z H2O | n Ba | Z Ba | M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0W | 0W | 0W | 0W | |||||

| 1W | 1W | 1W | 1W | |||||

| 2W | 2W | 2W | 2W | |||||

| 3W | 3W | 3W | 3W | |||||

| Dehydration | 40 | 60 | 0/60/40/0–R1 | - | - | - | - | |

| Start | 40 | 0/35/65/0–R1 | 1 | 10.70 | 0.15 | 10.70 | 9 | |

| 4 | 11.20/14.70 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 30 | 82 | 0/75/25/0–R0 | - | - | 0.15 | 9.00 | ||

| 12 | 35/65/0/0–R0 | 1 | 10.30 | 0.15 | 10.30 | 11 | ||

| 2 | 11.20/14.00 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 20 | 90 | 0/95/05/0–R0 | - | - | 0.15 | 9.00 | ||

| 10 | 35/65/0/0–R0 | 0.5 | 09.80 | 0.15 | 9.80 | 11 | ||

| 2 | 11.20/14.80 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 10 | 88 | 0/100/0/0 | - | - | 0.15 | 8.90 | ||

| 12 | 35/65/0/0–R0 | 0.5 | 9.50 | 0.15 | 9.50 | 8 | ||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| Hydration | 20 | 80 | 0/95/05/0–R0 | - | - | 0.15 | 8.90 | |

| 20 | 25/75/0/0–R0 | 0.5 | 10.20 | 0.15 | 10.20 | 8 | ||

| 2 | 10.80/14.00 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 30 | 75 | 0/75/25/0–R0 | - | - | 0.15 | 9.00 | ||

| 25 | 20/80/0/0–R0 | 1 | 10.70 | 0.15 | 10.70 | 9 | ||

| 3 | 11.00/13.80 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 40 | 62 | 0/65/35/0–R0 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 38 | 0/15/85/0–R0 | 1 | 10.70 | 0.15 | 10.70 | 8 | ||

| 4 | 11.00/13.80 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 50 | 65 | 0/55/45/0–R1 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 35 | 0/0/100/0 | 2.5 | 09.80 | 0.15 | 9.80 | 8 | ||

| 5 | 11.30/14.00 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| - | - | - | - | |||||

| 60 | - | - | - | - | 8 | |||

| 49 | 0/65/35/0–R1 | 2.5 | 09.80 | 0.15 | 9.80 | |||

| 28.05 | 0/0/75/25–R0 | 5.2 | 11.30/14.70 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||

| 22.95 | 0/35/65/0–R0 | 7.5 | 10.30/14.80/16.60 | 0.15 | 14.80 | |||

| 70 | - | - | - | - | 8 | |||

| 58 | 0/0/85/15–R0 | 2.5 | 10.20 | 0.15 | 10.20 | |||

| 42 | 0/45/55/0–R1 | 5 | 11.00/13.80 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||

| 4.5 | 10.90/14.50/16.70 | 0.15 | 14.50 | |||||

| 80 | 58 | 0/60/40/0–R1 | - | - | - | - | 8 | |

| 42 | 0/0/65/35–R1 | 2.5 | 10.50 | 0.15 | 10.50 | |||

| 5.2 | 11.00/14.90 | 0.15 | 12.20 | |||||

| 7.5 | 10.90/14.90/16.20 | 0.15 | 14.90 | |||||

| Dehydration | 70 | 62 | 0/55/45/0–R1 | - | - | - | - | |

| 38 | 0/0/70/30–R1 | 2.5 | 10.50 | 0.15 | 10.50 | |||

| 5.2 | 11.00/14.90 | 0.15 | 12.20 | 8 | ||||

| 7.5 | 10.30/14.90/16.40 | 0.15 | 14.90 | |||||

| 60 | 70 | 0/0/85/15–R0 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 30 | 0/65/35/0–R1 | 2.2 | 9.80 | 0.15 | 9.80 | |||

| 5 | 11.20/14.80 | 0.15 | 12.10 | 8 | ||||

| 5.4 | 11.00/14.70/16.40 | 0.15 | 14.70 | |||||

| 50 | 55 | 0/0/85/15–R0 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 45 | 0/45/55/0–R1 | 1.5 | 9.90 | 0.15 | 9.90 | |||

| 4 | 11.20/14.00 | 0.15 | 12.10 | 8 | ||||

| 5.4 | 11.00/14.70/16.40 | 0.15 | 14.70 | |||||

| 40 | 40 | 0/70/30/0–R1 | - | - | - | - | 9 | |

| 39 | 0/0/100/0 | 1.5 | 10.00 | 0.15 | 10.00 | |||

| 21 | 0/40/60/0–R0 | 3 | 11.00–13.80 | 0.15 | 12.00 | |||

| - | - | - | - |

Evolution of Hydration State’s Contributions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Volzone, C.; Rinaldi, J.O.; Ortiga, J. Retention of gases by hexadecyltrimethylammonium-montmorillonite clays. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 79, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oueslati, W.; Meftah, M.; Rhaiem, H.B.; Amara, A.B.H. Cation Exchange Selectivity versus concentration of competing heavy metal cations (Pb2+, Zn2+): Case of Na-montmorillonite. Phys. Procedia 2009, 2, 1059–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monash, P.; Pugazhenthi, G. Development of Ceramic Supports Derived from Low-Cost Raw Materials for Membrane Applications and its Optimization Based on Sintering Temperature. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2011, 8, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.S.K.; Ramachandran, R.; Kalidhasan, S.; Rajesh, V.; Rajesh, N. Potential application of dodecylamine modified sodium montmorillonite as an effective adsorbent for hexavalent chromium. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 211–212, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Dai, Y.; Long, H.; Zhu, N.; Li, P.; Wu, J.; Dang, Z. Characterization of organo-montmorillonites and comparison for Sr(II) removal: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 191, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciela, P.Z.; Rikke, G.O.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Bjarne, W.S. Adsorption of the disinfectant benzalkonium chloride on montmorillonite. Synergistic effect in mixture of molecules with different chain lengths. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 128, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Košak, A.; Lobnik, A.; Bauman, M. Adsorption of Mercury(II); Lead(II), Cadmium(II) and Zinc(II) from Aqueous Solutions using Mercapto-Modified Silica Particles. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2013, 12, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijagbeni, C.O.; Baek, M.-H.; Kim, D.-S. Montmorillonite surface properties and sorption characteristics for heavy metal removal from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 166, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kailas, L.W.; Pradeep, K.; Shri, C.; Bina, N.P.; Tjoon, T.T. Adsorption of Cadmium Ions from Aqueous Solution Using Granular Activated Carbon and Activated Clay. Clean Soil Air Water 2010, 38, 649–656. [Google Scholar]

- Özkahraman, B.; Acar, I.; Emik, S. Removal of Cu2+ and Pb2+ Ions Using CMC Based Thermoresponsive Nanocomposite Hydrogel. Clean Soil Air Water 2011, 39, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, A.; Bradley, L.; Ray, M.; Eugene, Z.; Aleksey, V. Adsorption of heavy metal ions on mesoporous silica-modified montmorillonite containing a grafted chelate ligand. Appl. Clay Sci. 2012, 59–60, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.M.F.; Oliveira, M.M.; Avelino, M.C.; Fonseca, M.G.; Almeida, R.K.S.; Silva Filho, E.C. Adsorption of an industrial anionic dye by modified-KSF-montmorillonite: Evaluation of the kinetic, thermodynamic and equilibrium data. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 203, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, R.; Ray, S. K. Removal of congo red and methyl violet from water using nano clay filled composite hydrogels of poly acrylic acid and polyethylene glycol. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 260, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.; Salem, A.; Babaei, A.A. Preparation and characterization of nano porous bentonite for regeneration of semi-treated waste engine oil: Applied aspects for enhanced recovery. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 260, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iucolano, F.; Caputo, D.; Colella, C. Permanent and safe storage of Ba2+ in hardened phillipsite-rich tuff/cement pastes. Appl. Clay Sci. 2005, 28, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.C.; Brady, P.V.; Arthur, S.E.; Zhou, W.Q.; Sawyer, D.; Hesterberg, D.A. Adsorption of barium(II) on montmorillonite: An EXAFS study. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2001, 190, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, M.; Oueslati, W.; Rhaiem, H.B.; Amara, A.B.H. Effect of the hydration sequence orientation on the structural properties of Hg exchanged montmorillonite: Quantitative XRD analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1604–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, M.L.; Pablo, L.; García, T.A. Adsorption of Ba2+ by Ca-exchange clinoptilolite tuff and montmorillonite clay. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 175, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaeser, R.; Méring, J. Isothermes d’hydratation des montmorillonites biioniques (Ca, Na). Clay Mineral. Bull. 1954, 2, 188–193. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harward, M.E.; Brindley, G.W. Swelling properties of synthetic smectites in relation to lattice substitutions. Clays Clay Miner. 1965, 13, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harward, M.E.; Carstea, D.D.; Sayegh, A.H. Properties of vermiculites and smectites: Expansion and collapse. Clays Clay Miner. 1969, 16, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Sato, T. Expansion characteristics of montmorillonite and saponite under various relative humidity conditions. Clay Sci. 1988, 7, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T.; Watanabe, T.; Otsuka, R. Effects of layer charge, charge location, and energy change on expansion properties of dioctahedral smectites. Clays Clay Miner. 1992, 40, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, H.; Nakazawa, H.; Hashizume, H.; Shimomura, S.; Watanabe, T. Hydration behavior of Na-smectite crystals synthetised at high pressure and high temperature. Clays Clay Miner. 1994, 42, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, D.A. Influence of layer charge on swelling of smectites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2006, 34, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Murakami, T.; Watanabe, T. Change in layer charge of smectites and smectite layers in illite/smectite during diagenetic alteration. Clays Clay Miner. 1996, 44, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueslati, W.; Rhaiem, H.B.; Amara, A.B.H. Effect of relative humidity constraint on the metal exchanged montmorillonite performance: An XRD profile modeling approach. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 261, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, W.F. Baseline studies of the clay minerals society source clays: Geological Origin. Clays Clay Miner. 2001, 49, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mermut, A.R.; Cano, A.F. Baseline studies of the clay minerals society source clays: Chemical analyses of major elements. Clay Clay Miner. 2001, 49, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, D.; Giese, R.F. Baseline studies of the clay minerals society source clays: Cation exchange capacity measurements by the ammonia-electrode method. Clay Clay Miner. 2001, 49, 444–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srodon, J.; Morgan, D.J.; Eslinger, E.V.; Eberl, D.D.; Karlinger, M.R. Chemistry of illite/smectite and end-member illite. Clays Clay Miner. 1986, 34, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.W. Nomenclature for regular interstratifications. Am. Mineral. 1982, 67, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrage, E.; Lanson, B.; Sakharov, B.A.; Geoffroy, N.; Jacquot, E.; Drits, V.A. Investigation of smectite hydration properties by modeling of X-ray diffraction profiles. Part 2. Influence of layer charge and charge location. Am. Mineral. 2007, 92, 1731–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrage, E.; Lanson, B.; Michot, L.; Robert, J.L. Hydration properties and interlayer organization of water and ions in synthetic Na-smectite with tetrahedral layer charge. Part 1. Results from X-ray diffraction profile modeling. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 4515–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oueslati, W.; Rhaiem, H.B.; Amara, A.B.H. XRD investigations of hydrated homoionic montmorillonite saturated by several heavy metal cations. Desalination 2011, 271, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drits, V.A.; Tchoubar, C. X-ray Diffraction by Disordered Lamellar Structures: Theory and Applications to Microdivided Silicates and Carbons; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1990; p. 371. [Google Scholar]

- Oueslati, W.; Meftah, M.; Chalghaf, R.; Rhaiem, H.B.; Amara, A.B.H. XRD investigation of selective exchange process for di-octahedral smectite: Case of solution saturated by Cu2+ and Co2+ cation. Z. Kristallogr. Proc. 2011, 1, 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Oueslati, W.; Rhaiem, H.B.; Lanson, B.; Amara, A.B.H. Selectivity of Na–montmorillonite in relation with the concentration of bivalent cation (Cu2+, Ca2+, Ni2+) by quantitative analysis of XRD patterns. Appl. Clay Sci. 2009, 43, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, M.; Oueslati, W.; Rhaiem, H.B.; Amara, A.B.H. XRD profile modeling approach tools to investigate the effect of charge location on hydration behavior in the case of metal exchanged smectite. Powder Diffr. 2013, 28, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammarm, M.; Oueslatim, W.; Rhaiemm, H.B.; Amara, A.B.H. Quantitative XRD analysis of the dehydration–hydration performance of (Na+, Cs+) exchanged smectite. Desalination Water Treat. 2014, 52, 4314–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atun, J.G.; Bascetin, E. Adsorption of barium on kaolinite, illite and montmorillonite at various ionic strengths. Radiochim. Acta 2004, 91, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérend, I.; Cases, J.M.; François, M.; Uriot, J.P.; Michot, L.J.; Masion, A.; Thomas, F. Mechanism of adsorption and desorption of water vapour by homoionic montmorillonites: The Li+, Na+, K+, Rb+ and Cs+ exchanged forms. Clays Clay Miner. 1995, 43, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greathouse, J.; Johnson, K.; Greenwell, H. Interaction of Natural Organic Matter with Layered Minerals: Recent Developments in Computational Methods at the Nanoscale. Minerals 2014, 4, 519–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cases, J.M.; Bérend, I.; François, M.; Uriot, J.P.; Michot, L.J.; Thomas, F. Mechanism of adsorption and desorption of water vapour by homoionic montmorillonite: The Mg2+, Ca2+, Sr2+ and Ba2+ exchanged forms. Clays Clay Miner. 1997, 45, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrage, E.; Lanson, B.; Sakharov, B.A.; Drits, V.A. Investigation of smectite hydration properties by modeling of X-ray diffraction profiles. Part 1. Montmorillonite hydration properties. Am. Miner. 2005, 90, 1358–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calarge, L.; Lanson, B.; Meunier, A.; Formoso, M.L. The smectiticminerals in a bentonite deposit from Melo (Uruguay). Clay Miner. 2003, 38, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meunier, A.; Lanson, B.; Velde, B. Composition variation of illitevermiculite-smectite mixed-layer minerals in a bentonite bed from charente. Clay Miner. 2004, 39, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oueslati, W.; Karmous, M.S.; Rhaiem, H.B.; Lanson, B.; Amara, A.B.H. Effect of interlayer cation and relative humidity on the hydration properties of a dioctahedral smectite. Z. Kristallogr. Suppl. 2007, 26, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oueslati, W.; Ammar, M.; Chorfi, N. Quantitative XRD Analysis of the Structural Changes of Ba-Exchanged Montmorillonite: Effect of an in Situ Hydrous Perturbation. Minerals 2015, 5, 507-526. https://doi.org/10.3390/min5030507

Oueslati W, Ammar M, Chorfi N. Quantitative XRD Analysis of the Structural Changes of Ba-Exchanged Montmorillonite: Effect of an in Situ Hydrous Perturbation. Minerals. 2015; 5(3):507-526. https://doi.org/10.3390/min5030507

Chicago/Turabian StyleOueslati, Walid, Marwa Ammar, and Nejmeddine Chorfi. 2015. "Quantitative XRD Analysis of the Structural Changes of Ba-Exchanged Montmorillonite: Effect of an in Situ Hydrous Perturbation" Minerals 5, no. 3: 507-526. https://doi.org/10.3390/min5030507

APA StyleOueslati, W., Ammar, M., & Chorfi, N. (2015). Quantitative XRD Analysis of the Structural Changes of Ba-Exchanged Montmorillonite: Effect of an in Situ Hydrous Perturbation. Minerals, 5(3), 507-526. https://doi.org/10.3390/min5030507