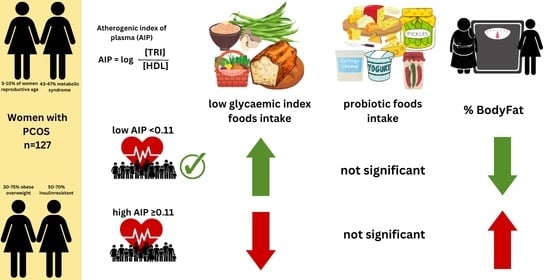

Intake of Low Glycaemic Index Foods but Not Probiotics Is Associated with Atherosclerosis Risk in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Atherogenic Markers

2.3. Food Frequency Intake and Diet Quality Indexes

- What is the usual fat content of dairy products you consume?

- Do you consume sweetened milk drinks and desserts for snacks?

- Do you consume non-sweetened milk drinks and desserts for snacks?

2.4. Body Composition

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El Hayek, S.; Bitar, L.; Hamdar, L.H.; Mirza, F.G.; Daoud, G. Poly Cystic Ovarian Syndrome: An Updated Overview. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, T. Diagnosis and Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Nurs. Stand. 2016, 94, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluzna, M.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Wachowiak-Ochmanska, K.; Moczko, J.; Kaczmarek, J.; Janicki, A.; Piatek, K.; Ruchała, M.; Ziemnicka, K. Effect of Central Obesity and Hyperandrogenism on Selected Inflammatory Markers in Patients with PCOS: A WHtR-Matched Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Chae, S.J.; Choi, Y.M.; Hwang, K.R.; Song, S.H.; Yoon, S.H.; Kim, S.M.; Ku, S.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.G.; et al. Atherogenic Changes in Low-Density Lipoprotein Particle Profiles Were Not Observed in Non-Obese Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 1354–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Himelein, M.J.; Thatcher, S.S. Depression and Body Image among Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczuko, M.; Skowronek, M.; Zapałowska-Chwyć, M.; Starczewski, A. Quantitative Assessment of Nutrition in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2016, 67, 419–426. [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi, G.; Giosuè, A.; Calabrese, I.; Vaccaro, O. Dietary Recommendations for Prevention of Atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 1188–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykowska-Derda, A.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Kaluzna, M.; Ruchala, M.; Ziemnicka, K. Diet Quality Scores in Relation to Fatness and Nutritional Knowledge in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Case–Control Study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 24, 3389–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Lonnie, M.; Wadolowska, L.; Frelich, A. “Cutting Down on Sugar” by Non-Dieting Young Women: An Impact on Diet Quality on Weekdays and the Weekend. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wanders, D.; Graff, E.C.; White, B.D.; Judd, R.L. Niacin Increases Adiponectin and Decreases Adipose Tissue Inflammation in High Fat Diet-Fed Mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suzuki, H.; Kunisawa, J. Vitamin-Mediated Immune Regulation in the Development of Inflammatory Diseases. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2015, 15, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, S.; Izadi, A.; Shirazi, S.; Parizad, M.; Pourghassem Gargari, B. The Effect of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Inflammatory and Endothelial Dysfunction Markers in Overweight/Obese Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Patients. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2021, 37, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samimi, M.; Zarezade Mehrizi, M.; Foroozanfard, F.; Akbari, H.; Jamilian, M.; Ahmadi, S.; Asemi, Z. The Effects of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Glucose Metabolism and Lipid Profiles in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin. Endocrinol. 2017, 86, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamali, M.; Gholizadeh, M. The Effects of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation on Metabolic Profiles and Parameters of Mental Health in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2022, 38, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teegarden, D.; Donkin, S.S. Vitamin D: Emerging New Roles in Insulin Sensitivity. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2009, 22, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heshmati, J.; Golab, F.; Morvaridzadeh, M.; Potter, E.; Akbari-Fakhrabadi, M.; Farsi, F.; Tanbakooei, S.; Shidfar, F. The Effects of Curcumin Supplementation on Oxidative Stress, Sirtuin-1 and Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor γ Coactivator 1α Gene Expression in Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) Patients: A Randomised Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, J.; Moini, A.; Sepidarkish, M.; Morvaridzadeh, M.; Salehi, M.; Palmowski, A.; Mojtahedi, M.F.; Shidfar, F. Effects of Curcumin Supplementation on Blood Glucose, Insulin Resistance and Androgens in Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomised Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Phytomedicine 2021, 80, 153395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio-Jiménez, C.; Martínez-Ramírez, M.J.; Gil, Á.; Gómez-Llorente, C. Effects of Probiotics on Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dong, Y.; Xu, M.; Chen, L.; Bhochhibhoya, A. Probiotic Foods and Supplements Interventions for Metabolic Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Clinical Trials. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 74, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio-Jiménez, C.; Martínez-Ramírez, M.J.; Del Castillo-Codes, I.; Arraiza-Irigoyen, C.; Tercero-Lozano, M.; Camacho, J.; Chueca, N.; García, F.; Olza, J.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; et al. Lactobacillus Reuteri V3401 Reduces Inflammatory Biomarkers and Modifies the Gastrointestinal Microbiome in Adults with Metabolic Syndrome: The PROSIR Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pei, R.; Martin, D.A.; DiMarco, D.M.; Bolling, B.W. Evidence for the Effects of Yogurt on Gut Health and Obesity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1569–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejtahed, H.S.; Mohtadi-Nia, J.; Homayouni-Rad, A.; Niafar, M.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M.; Mofid, V.; Akbarian-Moghari, A. Effect of Probiotic Yogurt Containing Lactobacillus Acidophilus and Bifidobacterium Lactis on Lipid Profile in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 3288–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakkar, P.N.; Patel, A.; Modi, H.A.; Prajapati, J.B. Hypocholesterolemic Effect of Potential Probiotic Lactobacillus Fermentum Strains Isolated from Traditional Fermented Foods in Wistar Rats. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.-T.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, Y.-Y.; Ma, Y.-T.; Xie, X. Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP): A Novel Predictive Indicator for the Coronary Artery Disease in Postmenopausal Women. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remely, M.; Tesar, I.; Hippe, B.; Gnauer, S.; Rust, P.; Haslberger, A.G. Gut Microbiota Composition Correlates with Changes in Body Fat Content Due to Weight Loss. Benef. Microbes 2015, 6, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, Y.; Santacruz, A.; Gauffin, P. Gut Microbiota in Obesity and Metabolic Disorders. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flak, M.B.; Neves, J.F.; Blumberg, R.S. Welcome to the Microgenderome. Science 2013, 339, 1044–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, Y.; Qi, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, L.; Wen, S.; Liu, Y.; Tang, L. Association between Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Gut Microbiota. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, G.E.; Lindenmayer, A.W.; McConchie, G.A.; Ryan, M.M.; Davidson, Z.E. Describing Nutrition in Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Systematic Review. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2016, 26, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qin, C.; Dong, L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, L. Whole Grain Benefit: Synergistic Effect of Oat Phenolic Compounds and β-Glucan on Hyperlipidemia via Gut Microbiota in High-Fat-Diet Mice. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12686–12696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałużna, M.; Pawlaczyk, K.; Schwermer, K.; Hoppe, K.; Człapka-Matyasik, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Sawicka-Gutaj, N.; Minczykowski, A.; Ziemnicka, K.; Oko, A.; et al. Adropin and Irisin: New Biomarkers of Cardiac Status in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease? A Preliminary Study. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 28, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivey, K.L.; Hodgson, J.M.; Kerr, D.A.; Thompson, P.L.; Stojceski, B.; Prince, R.L. The Effect of Yoghurt and Its Probiotics on Blood Pressure and Serum Lipid Profile; a Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frohlich, J.; Dobiášová, M. Fractional Esterification Rate of Cholesterol and Ratio of Triglycerides to HDL-Cholesterol Are Powerful Predictors of Positive Findings on Coronary Angiography. Clin. Chem. 2003, 49, 1873–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berneis, K.; Rizzo, M.; Hersberger, M.; Rini, G.B.; Di Fede, G.; Pepe, I.; Spinas, G.A.; Carmina, E. Atherogenic Forms of Dyslipidaemia in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2009, 63, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowski, K.C.; Skowrońska-Jóźwiak, E.; Łukasiak, K.; Gałuszko, K.; Dukowicz, A.; Cedro, M.; Lewiński, A. How Much Insulin Resistance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome? Comparison of HOMA-IR and Insulin Resistance (Belfiore) Index Models. Arch. Med. Sci. 2019, 15, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobiásová, M. AIP—Atherogenic index of plasma as a significant predictor of cardiovascular risk: From research to practice. Vnitr. Lek. 2006, 52, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kowalkowska, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Czarnocinska, J.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Galinski, G.; Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Bronkowska, M.; Dlugosz, A.; Loboda, D.; Wyka, J. Reproducibility of a Questionnaire for Dietary Habits, Lifestyle and Nutrition Knowledge Assessment (KomPAN) in Polish Adolescents and Adults. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kowalkowska, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Czarnocinska, J.; Galinski, G.; Dlugosz, A.; Loboda, D.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M. Data-Driven Dietary Patterns and Diet Quality Scores: Reproducibility and Consistency in Sex and Age Subgroups of Poles Aged 15–65 Years. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobas, K.; Wadolowska, L.; Slowinska, M.A.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Wuenstel, J.; Niedzwiedzka, E. Like Mother, Like Daughter? Dietary and Non-Dietary Bone Fracture Risk Factors in Mothers and Their Daughters. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadolowska, L.; Ulewicz, N.; Sobas, K.; Wuenstel, J.W.; Slowinska, M.A.; Niedzwiedzka, E.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M. Dairy-Related Dietary Patterns, Dietary Calcium, Body Weight and Composition: A Study of Obesity in Polish Mothers and Daughters, the MODAF Project. Nutrients 2018, 10, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cleghorn, C.L.; Harrison, R.A.; Ransley, J.K.; Wilkinson, S.; Thomas, J.; Cade, J.E. Can a Dietary Quality Score Derived from a Short-Form FFQ Assess Dietary Quality in UK Adult Population Surveys? Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2915–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). WHO|Waist Circumference and Waist–Hip Ratio. Report of a WHO Expert Consultation; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Saadati, K.; Chaboksavar, F.; Jahangasht Ghoozlu, K.; Shamsalinia, A.; Kordbageri, M.R.; Ghadimi, R.; Porasgari, Z.; Ghaffari, F. Evaluation of Psychometric Properties of Dietary Habits, Lifestyle, Food Frequency Consumption, and Nutritional Beliefs (KomPAN) Questionnaire in Iranian Adults. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1049909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudacher, H.M.; Scholz, M.; Lomer, M.C.; Ralph, F.S.; Irving, P.M.; Lindsay, J.O.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.; Whelan, K. Gut Microbiota Associations with Diet in Irritable Bowel Syndrome and the Effect of Low FODMAP Diet and Probiotics. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudacher, H.M.; Lomer, M.C.E.; Farquharson, F.M.; Louis, P.; Fava, F.; Franciosi, E.; Scholz, M.; Tuohy, K.M.; Lindsay, J.O.; Irving, P.M.; et al. A Diet Low in FODMAPs Reduces Symptoms in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome and A Probiotic Restores Bifidobacterium Species: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Karakula-Juchnowicz, H.; Rog, J.; Juchnowicz, D.; Łoniewski, I.; Skonieczna-Ydecka, K.; Krukow, P.; Futyma-Jedrzejewska, M.; Kaczmarczyk, M. The Study Evaluating the Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on the Mental Status, Inflammation, and Intestinal Barrier in Major Depressive Disorder Patients Using Gluten-Free or Gluten-Containing Diet (SANGUT Study): A 12-Week, Randomized, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Clinical Study Protocol. Nutr. J. 2019, 18, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wasilewski, A.; Zielińska, M.; Storr, M.; Fichna, J. Beneficial Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics, and Psychobiotics in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 1674–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on evaluation of Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food includig Power Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria. In Probiotics in Food Health and Nutritional Properties and Guidelines for Evaluation FAO Food and Nutrition Paper; WHO/FAO: Cordoba, Argentina, 2001.

- Gibson, G.R.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary Modulation of the Human Colonic Microbiota: Introducing the Concept of Prebiotics. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, X. Dietary Polyphenols: Regulate the Advanced Glycation End Products-RAGE Axis and the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis to Prevent Neurodegenerative Diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, A.; Mancin, L.; Giacona, M.C.; Bianco, A.; Caprio, M. Effects of a Ketogenic Diet in Overweight Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bai, W.-P.; Jiang, B.; Bai, L.-R.; Gu, B.; Yan, S.-X.; Li, F.-Y.; Huang, B. Ketogenic Diet in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Liver Dysfunction Who Are Obese: A Randomised, Open-Label, Parallel-Group, Controlled Pilot Trial. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2021, 47, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincione, R.I.; Losavio, F.; Ciolli, F.; Valenzano, A.; Cibelli, G.; Messina, G.; Polito, R. Effects of Mixed of a Ketogenic Diet in Overweight and Obese Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graff, S.K.; Mário, F.M.; Alves, B.C.; Spritzer, P.M. Dietary Glycemic Index Is Associated with Less Favorable Anthropometric and Metabolic Profiles in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Women with Different Phenotypes. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Hadi, A.; Pierson, R.A.; Lujan, M.E.; Zello, G.A.; Chilibeck, P.D. Effects of Dietary Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load on Cardiometabolic and Reproductive Profiles in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panjeshahin, A.; Salehi-Abargouei, A.; Anari, A.G.; Mohammadi, M.; Hosseinzadeh, M. Association between Empirically Derived Dietary Patterns and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. Nutrition 2020, 79–80, 110987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahdadian, F.; Ghiasvand, R.; Abbasi, B.; Feizi, A.; Saneei, P.; Shahshahan, Z. Association between Major Dietary Patterns and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Evidence from a Case-Control Study. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 44, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czlapka-Matyasik, M.; Gramza-Michalowska, A. The Total Dietary Antioxidant Capacity, Its Seasonal Variability, and Dietary Sources in Cardiovascular Patients. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Człapka-Matyasik, M.; Ast, K. Total Antioxidant Capacity and Its Dietary Sources and Seasonal Variability in Diets of Women with Different Physical Activity Levels. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2014, 64, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samimi, M.; Dadkhah, A.; Haddad Kashani, H.; Tajabadi-Ebrahimi, M.; Seyed Hosseini, E.; Asemi, Z. The Effects of Synbiotic Supplementation on Metabolic Status in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomised Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Cho, Y.K.; Kim, Y.-J.; Jung, C.H.; Lee, W.J.; Park, J.-Y.; Huh, J.H.; Kang, J.G.; Lee, S.J.; Ihm, S.-H. Association of the Atherogenic Index of Plasma with Cardiovascular Risk beyond the Traditional Risk Factors: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.; Rosner, B.; Willett, W.W.; Sacks, F.M. Cholesterol-Lowering Effects of Dietary Fiber: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ooi, L.G.; Liong, M.T. Cholesterol-Lowering Effects of Probiotics and Prebiotics: A Review of in Vivo and in Vitro Findings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2499–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Janiszewska, J.; Ostrowska, J.; Szostak-Węgierek, D. Milk and Dairy Products and Their Impact on Carbohydrate Metabolism and Fertility-A Potential Role in the Diet of Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phy, J.L.; Pohlmeier, A.M.; Cooper, J.A.; Watkins, P.; Spallholz, J.; Harris, K.S.; Berenson, A.B.; Boylan, M. Low Starch/Low Dairy Diet Results in Successful Treatment of Obesity and Co-Morbidities Linked to Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) HHS Public Access. J. Obes. Weight. Loss Ther. 2015, 5, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, K.A.; Cromer, G.; Burhans, M.S.; Kuzma, J.N.; Hagman, D.K.; Fernando, I.; Murray, M.; Utzschneider, K.M.; Holte, S.; Kraft, J.; et al. Impact of Low-Fat and Full-Fat Dairy Foods on Fasting Lipid Profile and Blood Pressure: Exploratory Endpoints of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Food Group | Products Included |

|---|---|

| proDI-4 1 | (1) Fermented milk drinks, (2) Pickled vegetables, (3) Fresh cheese-curd products, (4) Cheese |

| lGIDI-4 2 | (1) Wholemeal bread, (2) Buckwheat, oats, whole-grain pasta or other coarse-ground grains, (3) Legume-based foods, (4) Vegetables |

| pHDI-10 3 | (1) Wholemeal bread, (2) Buckwheat, oats, whole-wheat pasta, (3) Milk, (4) Fermented milk drinks, (5) Fresh cheese-curd products, (6) White meat, (7) Fish, (8) Legume-based foods, (9) Fruits, (10) Vegetables |

| nHDI-14 4 | (1) White bread, (2) White rice, pasta, fine-ground grains (3) Fast food, (4) Fried dishes, (5) Butter, (6) Lard, (7) Cheese, (8) Cold meats, smoked sausages, hot dogs, (9) Red meat dishes, (10) Sweets, (11) Tinned meats, (12) Sweetened carbonated and non-carbonated drinks, (13) Energy drinks, (14) Alcoholic beverages |

| Variable | Low AIP (n = 68) | High AIP (n = 59) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median (CI95%) | Mean ± SD | Median (CI95%) | p | |

| Age (y) | 26 ± 5 | 25 (4; 6) | 26 ± 6 | 25 (5; 7) | 0.74 |

| Body mass (kg) | 66.4 ± 11.2 | 63.6 (11.2; 9.6) | 75.3 ± 16.1 | 72.7 (13.6; 19.7) | 0.00 * |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.5 ± 3.3 | 22.9 (2.9; 4.0) | 27.4 ± 5.7 | 26.8 (4.8; 7.0) | 0.00 * |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 77.3 ± 9.9 | 76.0 (8.4; 11.9) | 86.5 ± 14.3 | 88.0 (12; 18) | 0.00 * |

| WHR (-) | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 0.78 (0.05; 0.07) | 0.84 ± 0.10 | 0.80 (0.09; 0.12) | 0.00 * |

| FM (%) | 37.2 ± 22.9 | 33.0 (19.5; 27.7) | 45.8 ± 25.8 | 41.1 (21.8; 31.6) | 0.05 |

| FFM (%) | 70.5 ± 16.9 | 68.2 (14.4; 20.5) | 66.9 ± 21.2 | 60.5 (17.9; 26.1) | 0.30 |

| T. Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 170.6 ± 29.2 | 168.5 (25.0; 35.2) | 187.4 ± 32.0 | 185.0 (27.1; 39.2) | 0.00 * |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 75 ± 14 | 73.0 (12.0; 16.9) | 55 ± 11 | 55.0 (9.0; 13.0) | 0.00 * |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 84 ± 25 | 83.0 (21.5; 30.3) | 108 ± 30 | 110.4 (25.7; 37.1) | 0.00 * |

| TG (mg/dL) | 55 ± 15 | 53.0 (12.7; 17.9) | 123 ± 67 | 103 (56; 81) | 0.00 * |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 87 ± 7 | 88 (6; 9) | 91 ± 7 | 90 (5.6; 8.0) | 0.00 * |

| Fasting insulin (uU/mL) | 8.10 ± 3.63 | 7.35 (3.10; 4.37) | 14.59 ± 8.58 | 12.4 (7.3; 10.5 | 0.00 * |

| HOMA-IR (-) | 1.79 ± 0.89 | 1.58 (0.76; 1.07) | 3.37 ± 2.19 | 2.9 (1.8; 2.7) | 0.00 * |

| AIP 1 (-) | −0.33 ± 0.29 | −0.35 (0.25; 0.36) | 0.73 ± 0.55 | 0.59 (0.47; 0.67) | 0.00 * |

| proDI-4 2 (%) | 13.85 ± 8.75 | 14.12 (7.48; 10.53) | 14.84 ± 8.26 | 14.00 (6.99; 10.10) | 0.52 |

| lGIDI-4 3 (%) | 30.47 ± 16.19 | 27.50 (13.85; 19.48) | 25.27 ± 14.29 | 26.75 (12.09; 17.46) | 0.05 * |

| pHDI-10 4 (%) | 27.50 ± 11.04 | 26.10 (9.44; 13.29) | 23.99 ± 10.72 | 20.3 (9.07; 13.10) | 0.07 |

| nHDI-14 5 (%) | 13.63 ± 7.83 | 11.39 (6.70; 9.43) | 13.92 ± 8.03 | 11.86 (6.80; 9.82) | 0.83 |

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Unsweetened milk drinks as a snack | 25 | 20 | 21 | 17 | 0.89 |

| Sweetened milk drinks as a snack | 12 | 9 | 18 | 14 | 0.08 |

| Milk and milk drinks | 0.68 | ||||

| Whole fat | 27 | 21 | 27 | 21 | |

| Low fat | 30 | 24 | 27 | 21 | |

| Non-fat | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| No dairy | 9 | 7 | 4 | 3 | |

| Food Groups | Atherogenic Index of Plasma ≥ 0.11 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Occurrence (%)/n | Crude OR (CI 95%) | OR Adjusted for BMI and Age (CI 95%) | |

| Wholemeal (brown) bread/bread rolls | |||

| ≥once a day | (13)/16 | 1.21 (0.54; 2.72); p = 0.64 | 1.18 (0.48; 2.89); p = 0.71 |

| Buckwheat, oats, whole-grain pasta or other coarse-ground grains | |||

| ≥two times a week | (16)/20 | 0.38 (0.18; 0.79); p = 0.01 * | 0.35 (0.16; 0.78); p = 0.01 * |

| Pickled vegetables | |||

| ≥two times a week | (7)/9 | 1.35 (0.48; 3.80); p = 0.57 | 0.82 (0.24; 2.84); p = 0.76 |

| Milk (including flavoured milk, hot chocolate, or latte) | |||

| ≥once a day | (16)/19 | 0.64 (0.31; 1.33); p = 0.23 | 0.51 (0.22; 1.18); p = 0.11 |

| Fermented milk drinks, e.g., yoghurts, kefir (natural or flavoured) | |||

| ≥once a day | (8)/10 | 1.18 (0.45; 3.11); p = 0.73 | 0.96 (0.32; 2.85); p = 0.94 |

| Fresh cheese-curd products, e.g., cottage cheese, cream cheese, cheese-based puddings | |||

| ≥once a day | (2)/2 | 1.16 (0.16; 8.66); p = 0.86 | 1.03 (0.10; 10.4); p = 0.98 |

| White meat, e.g., chicken, turkey, rabbit | |||

| ≥two times a week | (35)/45 | 1.25 (0.56; 2.80); p = 0.59 | 1.25 (0.56; 2.80); p = 0.59 |

| Fish | |||

| ≥two times a week | (4)/5 | 0.61 (0.19; 1.95); p = 0.40 | 0.47 (0.13; 1.78); p = 0.26 |

| Legume-based foods, e.g., beans, peas, soybeans, lentils | |||

| ≥once a week | (16)/19 | 0.72 (0.35; 1.51); p = 0.38 | 0.60 (0.26; 1.37); p = 0.22 |

| ≥two times a week | (6)/7 | 0.60 (0.21; 1.55); p = 0.27 | 0.50 (0.16; 1.54); p = 0.22 |

| Fruits | |||

| ≥two times a day | (9)/12 | 0.66 (0.29; 1.52); p = 0.32 | 0.59 (0.23; 1.51); p = 0.27 |

| Vegetables | |||

| ≥two times a day | (17)/22 | 1.16 (0.56; 2.43); p = 0.68 | 1.21 (0.54; 2.70); p = 0.64 |

| White bread and bakery products, e.g., wheat bread, rye bread, wheat-rye bread, toast bread, bread rolls | |||

| ≥once a day | (14)/18 | 0.71 (0.34; 1.50); p = 0.36 | 0.98 (0.43; 2.26); p = 0.97 |

| White rice, white pasta, fine-ground groats, e.g., semolina, couscous | |||

| ≥two times a week | (12)/15 | 0.55 (0.26; 1.19); p = 0.13 | 0.67 (0.29; 1.56); p = 0.35 |

| Fast foods, e.g., potato chips/French fries, hamburgers, pizza, hot dogs | |||

| ≥once a week | (9)/11 | 0.81 (0.34; 1.95); p = 0.64 | 1.03 (0.40; 2.67); p = 0.95 |

| Fried foods (e.g., meat or flour-based foods such as dumplings, pancakes, etc.) | |||

| ≥two times a week | (20)/26 | 1.12 (0.52; 2.43); p = 0.77 | 1.12 (0.52; 2.43); p = 0.77 |

| Butter as a bread spread or as an addition to your meals/for frying/for baking, etc. | |||

| ≥once a day | (15)/19 | 1.06 (0.50; 2.27); p = 0.87 | 0.85 (0.36; 1.98); p = 0.70 |

| Lard as a bread spread, or as an addition to your meals/for frying/for baking, etc. | |||

| ≥once a week | (1)/1 | 0.28 (0.03; 2.60); p = 0.26 | 0.25 (0.02; 3.09); p = 0.27 |

| Cheese (including processed cheese and blue cheese) | |||

| ≥two times a week | (24)/30 | 1.10 (0.54; 2.22); p = 0.80 | 1.34 (0.61; 2.94); p = 0.46 |

| Cured meat, smoked sausages, hot dogs | |||

| ≥two times a week | (26)/33 | 1.35 (0.66; 2.73); p = 0.41 | 1.45 (0.66; 3.17); p = 0.35 |

| Red meat, e.g., pork, beef, veal, lamb, game | |||

| ≥two times a week | (16)/20 | 1.98 (0.88; 4.43); p = 0.10 | 1.81 (0.75; 4.36); p = 0.18 |

| Sweets, e.g., confectionery, biscuits, cakes, chocolate bars, cereal bars, etc. | |||

| ≥two times a week | (31)/39 | 1.06 (0.51; 2.23); p = 0.87 | 1.25 (0.55; 2.85); p = 0.59 |

| Tinned (jar) meats | |||

| ≥1–3 times a month | (9)/12 | 1.32 (0.53; 3.30); p = 0.54 | 0.94 (0.33; 2.67); p = 0.91 |

| Sweetened carbonated or still drinks | |||

| ≥two times a week | (6)/8 | 1.18 (0.41; 3.39); p = 0.76 | 0.92 (0.27; 3.08); p = 0.89 |

| Energy drinks | |||

| ≥once a week | (2)/2 | 0.76 (0.12; 4.80); p = 0.77 | 1.01 (0.14; 7.61); p = 0.99 |

| Alcoholic beverages | |||

| ≥once a week | (10)/13 | 0.79 (0.34; 1.79); p = 0.56 | 0.79 (0.32; 1.97); p = 0.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bykowska-Derda, A.; Kałużna, M.; Garbacz, A.; Ziemnicka, K.; Ruchała, M.; Czlapka-Matyasik, M. Intake of Low Glycaemic Index Foods but Not Probiotics Is Associated with Atherosclerosis Risk in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Life 2023, 13, 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13030799

Bykowska-Derda A, Kałużna M, Garbacz A, Ziemnicka K, Ruchała M, Czlapka-Matyasik M. Intake of Low Glycaemic Index Foods but Not Probiotics Is Associated with Atherosclerosis Risk in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Life. 2023; 13(3):799. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13030799

Chicago/Turabian StyleBykowska-Derda, Aleksandra, Małgorzata Kałużna, Agnieszka Garbacz, Katarzyna Ziemnicka, Marek Ruchała, and Magdalena Czlapka-Matyasik. 2023. "Intake of Low Glycaemic Index Foods but Not Probiotics Is Associated with Atherosclerosis Risk in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome" Life 13, no. 3: 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13030799

APA StyleBykowska-Derda, A., Kałużna, M., Garbacz, A., Ziemnicka, K., Ruchała, M., & Czlapka-Matyasik, M. (2023). Intake of Low Glycaemic Index Foods but Not Probiotics Is Associated with Atherosclerosis Risk in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Life, 13(3), 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13030799