Application of a Pharmacogenetics-Based Precision Medicine Model (5SPM) to Psychotic Patients That Presented Poor Response to Neuroleptic Therapy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

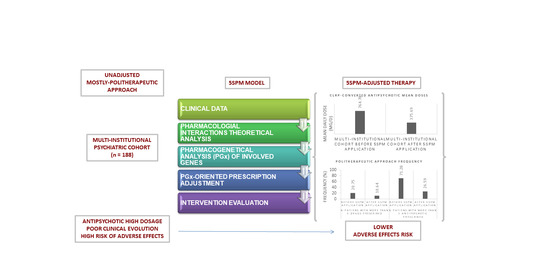

Step Precision Medicine

2.2. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Pharmacological Interactions

3.3. Drug-Gene Conflicts

3.4. Clinical Impact

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turner, T. Chlorpromazine: Unlocking psychosis. BMJ 2007, 334 (Suppl. 1), s7. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/334/suppl_1/s7 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieters, T.; Majerus, B. The introduction of chlorpromazine in Belgium and the Netherlands (1951–1968); tango between old and new treatment features. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. Part C Stud. Hist. Philos. Biol. Biomed. Sci. 2011, 42, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naber, D.; Haasen, C.; Perro, C. Clozapine: The first atypical antipsychotic. In Atypical Antipsychotics; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 145–162. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-0348-8448-8_8 (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Lally, J.; MacCabe, J.H. Antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: A review. Br. Med. Bull. 2015, 114, 169–179. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25957394/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heuvel, L.L.V.D. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific basis and practical applications (4th edition). J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2014, 26, 157–158. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2989/17280583.2014.914944 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, S.; Amrtavarshini, R.; Bhandary, R.P.; Praharaj, S.K. Frequency, reasons, and factors associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy in Schizophrenia: A retrospective chart review in a tertiary hospital in India. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102022. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1876201820301337 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.K. Antipsychotic Polypharmacy: A Dirty Little Secret or a Fashion? Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 23, 125–131. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ijnp/article/23/2/125/5684986 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamanouchi, Y.; Sukegawa, T.; Inagaki, A.; Inada, T.; Yoshio, T.; Yoshimura, R.; Iwata, N. Evaluation of the individual safe correction of antipsychotic agent polypharmacy in Japanese patients with chronic schizophrenia: Validation of safe corrections for antipsychotic polypharmacy and the high-dose method. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014, 18. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25522380/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamei, H.; Yamada, H.; Hatano, M.; Hanya, M.; Yamada, S.; Iwata, N. Effectiveness in Switching from Antipsychotic Polypharmacy to Monotherapy in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Case Series. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2020, 18, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasteridis, P.; Ride, J.; Gutacker, N.; Aylott, L.; Dare, C.; Doran, T.; Gilbody, S.; Goddard, M.; Gravelle, H.; Kendrick, T.; et al. Association Between Antipsychotic Polypharmacy and Outcomes for People With Serious Mental Illness in England. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 650–656. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31109263/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- König, I.R.; Fuchs, O.; Hansen, G.; Von Mutius, E.; Kopp, M.V. What is precision medicine? Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrasco-Ramiro, F.; Peiró-Pastor, R.; Aguado, B. Human genomics projects and precision medicine. Gene Ther. 2017, 24, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckmann, J.S.; Lew, D. Reconciling evidence-based medicine and precision medicine in the era of big data: Challenges and opportunities. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 1–11. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27993174/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liperoti, R.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Managing Antipsychotic Medications in Schizophrenia: Comprehensive Assessment and Personalized Care to Improve Clinical Outcomes and Reduce Costs. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 76, e1159–e1160. Available online: http://www.psychiatrist.com/jcp/article/pages/2015/v76n09/v76n0922.aspx (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Osmanova, D.Z.; Freidin, M.B.; Fedorenko, O.Y.; Pozhidaev, I.V.; Boiko, A.S.; Vyalova, N.M.; Tiguntsev, V.V.; Кoрнетoва, Е.; Loonen, A.J.M.; Semke, A.V.; et al. A pharmacogenetic study of patients with schizophrenia from West Siberia gets insight into dopaminergic mechanisms of antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia. BMC Med. Genet. 2019, 20, 35–44. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30967134/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, B.S.; McIntyre, R.S.; Gentle, J.E.; Park, N.S.; Chiriboga, D.A.; Lee, Y.; Singh, S.; McPherson, M.A. A computational algorithm for personalized medicine in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 192, 131–136. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28495491/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Cao, T.; Wu, X.; Tang, M.; Xiang, D.; Cai, H. Progress in genetic polymorphisms related to lipid disturbances induced by atypical antipsychotic drugs. Front. Pharmacol. Front. Media 2020, 10. Available online: /pmc/articles/PMC7011106/?report=abstract (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urichuk, L.; Prior, T.I.; Dursun, S.; Baker, G. Metabolism of Atypical Antipsychotics: Involvement of Cytochrome P450 Enzymes and Relevance for Drug-Drug Interactions. Curr. Drug Metab. 2008, 9, 410–418. Available online: http://www.eurekaselect.com/openurl/content.php?genre=article&issn=1389-2002&volume=9&issue=5&spage=410 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Herbild, L.; Andersen, S.E.; Rasmussen, H.B.; Jürgens, G.; Werge, T. Does Pharmacogenetic Testing for CYP450 2D6 and 2C19 Among Patients with Diagnoses within the Schizophrenic Spectrum Reduce Treatment Costs? Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 113, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.F.; Goldstein, D.B.; Angrist, M.; Cavalleri, G. Personalized medicine and human genetic diversity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Med. 2014, 4. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25059740/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pina-Camacho, L.; Díaz-Caneja, C.M.; Saiz, P.A.; Bobes, J.; Corripio, I.; Grasa, E. Estudio farmacogenético del tratamiento a largo plazo con antipsicóticos de segunda generación y sus efectos adversos metabólicos (Estudio SLiM): Justificación, objetivos, diseño y descripción de la muestra. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud. Ment. 2014, 7, 166–178. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25440735/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ravyn, D.; Ravyn, V.; Lowney, R.; Nasrallah, H.A. CYP450 Pharmacogenetic treatment strategies for antipsychotics: A review of the evidence. Schizophr. Res. 2013, 149, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, J.I. Clinical pharmacokinetics of antipsychotics. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1994, 34, 286–295. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7911807/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moons, T.; De Roo, M.; Claes, S.; Dom, G. Relationship between P-glycoprotein and second-generation antipsychotics. Pharmacogenomics 2011, 12, 1193–1211. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21843066/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zivković, M.; Mihaljević-Peles, A.; Bozina, N.; Sagud, M.; Nikolac-Perkovic, M.; Vuksan-Cusa, B.; Muck-Seler, D. The Association Study of Polymorphisms in DAT, DRD2, and COMT Genes and Acute Extrapyramidal Adverse Effects in Male Schizophrenic Patients Treated With Haloperidol. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 33, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassó, P.; Mas, S.; Bernardo, M.; Alvarez, S.; Parellada, E.; Lafuente, A. A common variant in DRD3 gene is associated with risperidone-induced extrapyramidal symptoms. Pharm. J. 2009, 9, 404–410. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19506579 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, R.R.; Smith, R.L. Addressing phenoconversion: The Achilles’ heel of personalized medicine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 79, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isidoro-García, M.; Sanchez-Martin, A.; Garcia-Berrocal, B. Impact of New Technologies on Pharmacogenomics. Curr. Pharm. Pers. Med. 2017, 14, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PharmGKB. Available online: https://www.pharmgkb.org/ (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Hoffmann, M.F.; Preissner, S.C.; Nickel, J.; Dunkel, M.; Preissner, R.; Preissner, S. The Transformer database: Biotransformation of xenobiotics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D1113–D1117. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24334957/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaedigk, A.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Miller, N.A.; Leeder, J.S.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Klein, T.E.; the PharmVar Steering Committee. The Pharmacogene Variation (PharmVar) Consortium: Incorporation of the Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Database. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 103, 399–401. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29134625 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Leon, J.; Susce, M.T.; Murray-Carmichael, E. The AmpliChipTM CYP450 Genotyping Test. Mol. Diagn Ther. 2012, 10, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, R.H. Cytochrome P450: Genotype to phenotype. Xenobiotica 2020, 50, 9–18. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31411087/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samer, C.; Lorenzini, K.I.; Rollason, V.; Daali, Y.; Desmeules, J.A. Applications of CYP450 Testing in the Clinical Setting. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2013, 17, 165–184. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s40291-013-0028-5 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venkatasubramanian, G.; Danivas, V. Current perspectives on chlorpromazine equivalents: Comparing apples and oranges! Indian J. Psychiatry 2013, 55, 207–208. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3696254/ (accessed on 12 October 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, Y.L.; Jin, H.; Zhang, W.; Qiang, E.; Shekhtman, D.; Shao, D.; Revoe, R.; Villamarin, E.; Ivanchenko, M.; Kimura, Z.Y.; et al. ALFA: Allele Frequency Aggregator; National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, U.S.: Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD, USA, 2020. Available online: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/docs/gsr/alfa/ (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Sheehan, J.J.; Sliwa, J.; Amatniek, J.; Grinspan, A.; Canuso, C. Atypical Antipsychotic Metabolism and Excretion. Curr. Drug Metab. 2010, 11, 516–525. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20540690/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samara, M.T.; Klupp, E.; Helfer, B.; Rothe, P.H.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Leucht, S. Increasing antipsychotic dose for non response in schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 5, CD011883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffman, J.C.; Chang, T.E.; Durham, L.E.; Weiss, A.P. Antipsychotic polytherapy on an inpatient psychiatric unit: How does clinical practice coincide with Joint Commission guidelines? Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2011, 33, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söderberg, M.M.; Haslemo, T.; Molden, E.; Dahl, M.-L. Influence of CYP1A1/CYP1A2 and AHR polymorphisms on systemic olanzapine exposure. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2013, 23, 279–285. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23492908 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kohlrausch, F.B.; Gama, C.S.; Lobato, M.I.; Belmontedeabreu, P.S.; Gesteira, A.; Barros-Angueira, F.; Carracedo, Á.; Hutz, M.H. Molecular diversity at theCYP2D6locus in healthy and schizophrenic southern Brazilians. Pharmacogenomics 2009, 10, 1457–1466. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19761369 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.U.; Citrome, L.; Haddad, P.M.; Lauriello, J.; Olfson, M.; Calloway, S.M. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in Schizophrenia: Evaluating the evidence. J. Clin. Psychiatry Physicians 2020, 77, 3–24. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27732772/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belmonte, C.; Ochoa, D.; Román, M.; Saiz-Rodríguez, M.; Wojnicz, A.; Gómez-Sánchez, C.I.; Martin-Vilchez, S.; Abad-Santos, F. Influence of CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5 and ABCB1 Polymorphisms on Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Aripiprazole in Healthy Volunteers. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 122, 596–605. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29325225/ (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Novalbos, J.; López-Rodríguez, R.; Roman, M.; Gallego-Sandín, S.; Ochoa, D.; Abad-Santos, F. Effects of CYP2D6 Genotype on the Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Safety of Risperidone in Healthy Volunteers. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 30, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, G.; Mihara, K.; Nakamura, A.; Suzuki, T.; Nemoto, K.; Kagawa, S. Prolactin concentrations during aripiprazole treatment in relation to sex, plasma drugs concentrations and genetic polymorphisms of dopamine D2 receptor and cytochrome P450 2D6 in Japanese patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 66, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patteet, L.; Vincent, H.; Kristof, M.; Bernard, S.; Manuel, M.; Hugo, N. Genotype and co-medication dependent CYP2D6 metabolic activity: Effects on serum concentrations of aripiprazole, haloperidol, risperidone, paliperidone and zuclopenthixol. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 72, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukic, M.M.; Smith, R.L.; Haslemo, T.; Molden, E.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. Effect of CYP2D6 genotype on exposure and efficacy of risperidone and aripiprazole: A retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 418–426. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31000417 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, K.; Mihara, K.; Nakamura, A.; Nagai, G.; Kagawa, S.; Suzuki, T.; Kondo, T. Effects of escitalopram on plasma concentrations of aripiprazole and its active metabolite, dehydroaripiprazole, in Japanese patients. Pharmacopsychiatry 2014, 47, 101–104. Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/321/CN-01051321/frame.html (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van der Weide, K.; van der Weide, J. The Influence of the CYP3A4*22 Polymorphism on Serum Concentration of Quetiapine in Psychiatric Patients. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 34, 256–260. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24525658 (accessed on 4 November 2020). [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| PATIENTS | |

| Total number of patients included: | 188 |

| - Average age | 47 (±13) |

| - Male: Female (%) | 59.58:37.77 |

| DIAGNOSTIC | |

| DSM-V * | n (%) |

| F03—Dementia | 1 (0.53) |

| F19—Substance-Related Disorder | 12 (6.38) |

| F20—Schizophrenia | 126 (67.02) |

| F22—Persistent Delusional Disorder | 2 (1.06) |

| F23—Brief and Acute Psychotic Disorder | 1 (0.53) |

| F25—Schizoaffective Disorder | 13 (6.92) |

| F31—Bipolar Disorder | 25 (13.30) |

| F33—Major Depressive Disorder | 1 (0.53) |

| F60—Specific Personality Disorders | 2 (1.06) |

| F61—Mixed Personality Disorder | 1 (0.53) |

| F79—Intellectual Disability | 2 (1.06) |

| Antipsychotic | Presentation | |

|---|---|---|

| Oral (n Before/After PGx) | IM (n Before/After PGx) | |

| Amisulpride | 14/7 | |

| Aripiprazole | 38/21 | 13/26 |

| Asenapine | 20/16 | |

| Olanzapine | 56/40 | |

| Paliperidone | 18/12 | 23 */66 * |

| Quetiapine | 71/20 | |

| Risperidone | 44/2 | 5/0 |

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| DRUG PRESCRIPTIONS (Pre-PGx Testing/Post-PGx Testing) | |

| Total Number of drugs (n): | 635/478 |

| - Average drugs | 3.67/3.11 |

| - Average Antipsychotics | 1.82/1.27 |

| - More than 5 drugs prescribed (% of total) | 20.75/10.64 |

| - More than 1 antipsychotic prescribed (% of total) | 71.28/26.60 |

| - Average Within-Patient Drug Variation (%) | −14.55 |

| - Average Within-Patient Antipsychotic Variation (%) | −23.63 |

| Medication classes (% of total) | |

| A. Digestive system and metabolic | 7.24/8.55 |

| B. Blood and hematopoietic organs | 0.32/0.00 |

| C. Cardiovascular system | 0.95/2.14 |

| D. Dermatologic medications | 0.00/0.00 |

| E. Genitourinary apparatus and sex hormones | 0.63/0.43 |

| H. Systemic hormone preparations excluded hormones | 2.68/4.06 |

| J. Anti-infectious in general for systemic use | 0.00/0.00 |

| L. Antineoplastic and immunomodulatory agents | 0.16/0.21 |

| M. Skeletal muscle | 0.00/0.00 |

| N. Nervous system (Total) | 87.72/86.74 |

| N1. Antipsychotics | 54.02/51.06 |

| P. antiparasitic products, insecticides, and repellents | 0.00/0.00 |

| R. respiratory system | 0.00/0.00 |

| S. organs of the senses | 0.00/0.00 |

| V. various | 0.32/0.00 |

| Pre-PGx (%) | Post-PGx (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Amisulpride (<400 mg) | 14 | 86 |

| Aripiprazole (<10 mg) | 16 | 4 |

| Asenapine (<5 mg) | 0 | 0 |

| Olanzapine (<10 mg) | 11 | 45 |

| Paliperidone (<6 mg) | 46 | 72 |

| Quetiapine (<400 mg) | 66 | 95 |

| Risperidone (<2 mg) | 6 | 0 |

| Gene | Alleles |

|---|---|

| 1A2 | *1F |

| 2B6 | *6 |

| 2C9 | *1 (WT), *2, *3 |

| 2C19 | *1 (WT), *2, *4, *17 |

| 2D6 | *1 (WT), *2, *3, *4, *5, *6, *7, *8, *9, *10, *12, *14, *17, *29, *41, *46 |

| 3A4 | *1B |

| 3A5 | *3C |

| n | PM | IM | EM | UM | HI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | 179 | - | - | 13.97% (n = 25) | 86.03% (n = 154) | |

| CYP2B6 | 166 | 9.04% (n = 15) | 40.96% (n = 68) | 50% (n = 83) | - | |

| CYP2C9 | 183 | 7.10% (n = 13) | 35.52% (n = 65) | 57.38% (n = 105) | - | |

| CYP2C19 | 186 | 3.23% (n = 6) | 20.43% (n = 38) | 47.85% (n = 89) | 27.96% (n = 52) | |

| CYP2D6 | 183 | 3.78% (n = 7) | 5.95% (n = 11) | 85.95% (n = 159) | 3. 24% (n = 6) | |

| CYP3A4 | 188 | 1.06% (n = 2) | 7.45% (n = 14) | 91.49% (n = 172) | - | |

| CYP3A5 | 187 | 87.85% (n = 159) | 13.81% (n = 25) | 1.66% (n = 3) | - |

| Major Metabolizer | Minor Metabolizer | Product | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olanzapine ^ | CYP1A2 | CYP2D6 *,# | Inactive |

| Aripiprazole | CYP2D6 #,‡, CYP3A4 | CYP3A5 * | Active |

| Risperidone | CYP2D6 # | CYP3A4 # | Active (Paliperidone) |

| Amisulpride | NO CYP | ||

| Clozapine | CYP1A2 #, CYP3A4 #,‡ | CYP2C19 *,#, CYP2C9 *,#, CYP2D6 #, CYP3A5 *,# | Reduced Activity, Inactive (CYP1A2/CYP3A4) |

| Paliperidone | NO CYP | ||

| Quetiapine | CYP3A4 | CYP3A5 *, CYP2D6 *,# | Inactive |

| Asenapine | CYP1A2 | CYP2D6 † | Inactive |

| Levomepromazine | CYP3A4 # | CYP1A2 | Inactive |

| n before PGx/ n after PGx (%) | 1A2 HI | 2D6 PM | 2D6 IM | 2D6 UM | 3A4 PM | 3A4 IM | 3A5 PM | 3A5 IM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole | - | 1 (14.3)/ 1 (14.3) | 1 (9.1)/ 2 (18.2) | 1 (16.7)/ 0 (0) | 1 (50)/0 (0) | 7 (50)/ 3 (21.4) | 42 (26.4)/ 42 (26.4) | 8 (32)/ 5 (20) |

| Asenapine | 11 (7.1)/ 11 (7.1) | 1 (14.3)/ 1 (14.3) | 2 (18.2)/ 2 (18.2) | 0 (0)/0 (0) | - | - | - | - |

| Clozapine | 34 (22.1)/ 21 (13.6) | 1 (14.3)/ 2 (28.6) | 1 (9.1)/ 1 (9.1) | 2 (33.3)/ 1 (16.7) | 0 (0)/ 1 (50) | 4 (28.6)/ 2 (14.3) | 31 (19.5)/ 21 (13.2) | 7 (28)/ 4 (16) |

| Olanzapine | 51 (33.1)/ 31 (20.1) | 3 (42.9)/ 3 (42.9) | 4 (36.4)/ 4 (36.4) | 1 (16.7)/ 1 (16.7) | - | - | - | - |

| Quetiapine | - | 2 (28.6)/ 0 (0) | 2 (18.2)/ 1 (9.1) | 3 (50)/ 1 (16.7) | 1 (50)/ 0 (0) | 5 (35.7)/ 1 (7.1) | 59 (37.1)/ 16 (10.1) | 11 (44)/ 4 (16) |

| Risperidone | - | 2 (28.6)/ 0 (0) | 2 (18.2)/ 0 (0) | 3 (50)/ 0 (0) | 0 (0)/ 0 (0) | 0 (0)/0 (0) | - | - |

| Pre-PGx | Post-PGx | Variation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Dose (mg/d) | Min Dose (mg/d) | Max Dose (mg/d) | Mean Dose (mg/d) | Min Dose (mg/d) | Max Dose (mg/d) | Mean Dose (mg/d) | Min Dose (mg/d) | Max Dose (mg/d) | |

| Olanzapine | 16.38 | 2.5 | 45 | 10.5 | 2.5 | 40 | −0.36 | 0 | −0.11 |

| Aripiprazole | 14.79 | 3 | 30 | 14.06 | 3 | 30 | −0.05 | 0 | 0 |

| Risperidone | 5.39 | 1 | 28.33 | 5.5 | 5 | 6 | 0.02 | 4 | −0.79 |

| Amisulpride | 514.29 | 100 | 1000 | 224.57 | 100 | 400 | −0.56 | 0 | −0.6 |

| Clozapine | 325 | 100 | 700 | 253.85 | 100 | 400 | −0.22 | 0 | −0.43 |

| Paliperidone | 7.08 | 3 | 14 | 5.89 | 3 | 9 | −0.17 | 0 | −0.36 |

| Quetiapine | 304.01 | 10 | 1200 | 199.5 | 40 | 600 | −0.34 | 3 | −0.5 |

| Asenapine | 11.75 | 5 | 20 | 10 | 5 | 20 | −0.15 | 0 | 0 |

| % Prescriptions | PrePGx | PostPGx | Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olanzapine | 29.8 | 21.3 | −28.6 |

| Aripiprazole (Oral) | 20.2 | 11.2 | −44.7 |

| Aripiprazole (IM) | 6.9 | 13.8 | +100.0 |

| Risperidone | 23.4 | 1.1 | −95.5 |

| Risperidone (IM) | 2.7 | 0 | −100.0 |

| Clozapine | 20.2 | 13.8 | −31.6 |

| Quetiapine | 37.8 | 10.6 | −71.8 |

| Asenapine | 10.6 | 8.5 | −20.0 |

| Amisulpride | 7.4 | 3.7 | −50.0 |

| Paliperidone (Oral) | 9.6 | 6.4 | −33.3 |

| Paliperidone (IM) | 12.2 | 35.1 | +186.9 |

| Excluding Therapy Switches | Including Therapy Switches | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotic | Mean Variation (%) (CI 95%) | Standard Deviation | Mean Variation (%) (CI 95%) | Standard Deviation |

| Olanzapine | −30.69 (−35.34, −26.04) | 32.54 | −30.75 (−42.43, −19.07) | 81.71 |

| Aripiprazole | 6.37 (−0.24, 12.98) | 46.22 | −3.22 (−15.19, 8.75) | 83.76 |

| Risperidone | 0 | 0 | −94 (−98.44, −89.56) | 31.05 |

| Amisulpride | −25 (−28.57, −21.43) | 25 | −39.48 (−51.88, −27.08) | 86.73 |

| Clozapine | −23.6 (−27.51, −19.69) | 27.33 | −27.54 (−39.87, −15.21) | 86.24 |

| Paliperidone | −3.7 (−8.32, 0.92) | 32.3 | 40.33 (29.86, 50.79) | 73.21 |

| Quetiapine | −24.38 (−30.38, −18.38) | 41.95 | −73.2 (−81.04, −65.36) | 54.87 |

| Asenapine | −13.89 (−16.78, −10.99) | 20.23 | −16.12 (−28.79, −3.44) | 88.67 |

| Mean Variation (%) (CI 95%) | Standard Deviation | |||

| Chlorpromazine Conversion | −36.4 (−42.12, −30.68) | 40.02 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carrascal-Laso, L.; Franco-Martín, M.Á.; García-Berrocal, M.B.; Marcos-Vadillo, E.; Sánchez-Iglesias, S.; Lorenzo, C.; Sánchez-Martín, A.; Ramos-Gallego, I.; García-Salgado, M.J.; Isidoro-García, M. Application of a Pharmacogenetics-Based Precision Medicine Model (5SPM) to Psychotic Patients That Presented Poor Response to Neuroleptic Therapy. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10040289

Carrascal-Laso L, Franco-Martín MÁ, García-Berrocal MB, Marcos-Vadillo E, Sánchez-Iglesias S, Lorenzo C, Sánchez-Martín A, Ramos-Gallego I, García-Salgado MJ, Isidoro-García M. Application of a Pharmacogenetics-Based Precision Medicine Model (5SPM) to Psychotic Patients That Presented Poor Response to Neuroleptic Therapy. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2020; 10(4):289. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10040289

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrascal-Laso, Lorena, Manuel Ángel Franco-Martín, María Belén García-Berrocal, Elena Marcos-Vadillo, Santiago Sánchez-Iglesias, Carolina Lorenzo, Almudena Sánchez-Martín, Ignacio Ramos-Gallego, M Jesús García-Salgado, and María Isidoro-García. 2020. "Application of a Pharmacogenetics-Based Precision Medicine Model (5SPM) to Psychotic Patients That Presented Poor Response to Neuroleptic Therapy" Journal of Personalized Medicine 10, no. 4: 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10040289

APA StyleCarrascal-Laso, L., Franco-Martín, M. Á., García-Berrocal, M. B., Marcos-Vadillo, E., Sánchez-Iglesias, S., Lorenzo, C., Sánchez-Martín, A., Ramos-Gallego, I., García-Salgado, M. J., & Isidoro-García, M. (2020). Application of a Pharmacogenetics-Based Precision Medicine Model (5SPM) to Psychotic Patients That Presented Poor Response to Neuroleptic Therapy. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 10(4), 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10040289