1. Introduction

As cultural World Heritage Sites, the Forbidden City in Beijing and the Shenyang Imperial Palace are two of the best-preserved ancient palaces in China. The Forbidden City was constructed between 1406 and 1420 by Zhu Di, an emperor of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). It is the largest existing palace complex in the world. The Shenyang Imperial Palace is located in the northeast region of China and was built by the early rulers of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) in 1625, followed by continuous construction by several emperors. After the ruler of the Qing dynasty overthrew the emperor of the Ming dynasty and moved into the Forbidden City in 1644, the Shenyang Imperial Palace became the emperor’s largest holiday palace, located outside of Beijing. The architecture of the Shenyang Imperial Palace has strong Manchu ethnic characteristics. The two palaces differ in their spatial form due to differences in the builders’ ethnic and cultural backgrounds, regional conditions, and construction techniques.

Scholars have conducted studies on the architecture of the two palaces. For the Beijing Forbidden City, Yu systematically introduced the technology and art of traditional Chinese architecture and synthesized the architectural art of the Forbidden City in terms of its construction history, planning, and design ideas [

1]. Bai and Huang pointed out that the royal palaces were the sites where the monarchs lived and exercised their autocratic kingship and were also centers of state power. These authors discussed the architectural embodiment of the concept of the supremacy of the monarchy [

2]. For the Shenyang Imperial Palace, Wu studied the architectural layout and decorative art [

3], while Chen and Wang emphasized that different architectural characteristics reflected different political and economic backgrounds, highlighting the important role of the political and economic context in the formation of architecture through an analysis of the architecture of the Shenyang Imperial Palace [

4]. Luo discussed the culture of the Shenyang Imperial Palace in three different architectural developmental stages, presenting clear cultural development and describing the basic trend of development of Manchu national culture [

5]. In general, current research on the architectural spaces of the two palaces is mainly qualitative in nature and lacks quantitative analysis of the related spatial features. No study has analyzed the correspondence between palace space and use functions, which means that no previous study has accurately compared the similarities and differences between the two palace spaces.

Space syntax quantifies and evaluates the spatial form of human settlements, including buildings, cities, and even landscapes, by treating space as an independent element. This approach can analyze the relationship between spaces at different scales and reveal the internal correlation between human activity patterns and spatial structure [

6,

7], explain human behavior and social activities from the perspective of spatial configuration [

8,

9], and even make distinctive contributions to research in social and urban history [

10]. Social factors also influence the production of space, creating foreground spaces that extend beyond the local and background spaces that are more supportive of local communities [

11]. Yamu et al. provided a holistic and compact overview of the various concepts used in space syntax, from their basic elements to analytical techniques and theories [

12]. Currently, space syntax theory is widely used in quantitative studies of various types of space, such as medical space [

13], traditional village space [

14], urban underground space [

15], urban block space [

16], urban park space [

17], and historical city space [

18]. This approach has also been applied in the study of palace building space worldwide. Nevadomsky used space syntax theory to conduct a quantitative analysis of the sites within Ogiamien’s palace and the chiefdom of other Benin kingdoms and compared the results using qualitative analysis to confirm the traditional social nature of the use of space in the chiefdom of the former kingdom [

19]. Baumanova and Smejda studied the palace building space on the Gede site near the coast of Kenya and found that the configuration and use of rooms in the palace, their position in the communication network, and the social and cultural content of the space changed with time [

20]. Eyal Regev’s study of Herodian palaces explored social relationships at court and showed that social interactions in the palace were hierarchical, emphasizing the privacy of the king and his control over the interactions of potential visitors [

21]. These studies show that space syntax not only provides a scientific basis for the quantitative analysis of the intricate spatial organization within palace complexes but also allows for consideration of the interactions between the function of the architectural spaces and the social and cultural activities that occurred within these spaces. However, the spatial differences between Chinese and Western palaces make it difficult to directly apply or refer to relevant Western research results. To date, relatively little academic research uses the space syntax approach with regard to Chinese palace spaces. Only Zhu has used the space syntax method to quantitatively analyze and confirm that the Forbidden City was the highest-ranked, most enclosed, and most inaccessible part of Beijing City [

22]. However, in Zhu’s study, there is a lack of corresponding analysis of the traditional architectural and cultural differences behind the spatial features and no comparison of the spatial organization of the Beijing Forbidden City with similar domestic or foreign royal palaces.

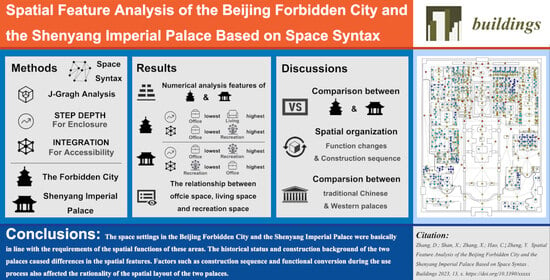

This paper aims to quantitatively analyze the spatial features of the Beijing Forbidden City and the Shenyang Imperial Palace, as well as the similarities and differences between them. First, the relational diagram method of space syntax theory is used to obtain the integration and depth values of various spaces in the two palaces in Beijing and Shenyang. Then, the differences in spatial organization characteristics reflected by these two values are compared. Finally, this study makes a spatial comparison between traditional Chinese and Western palaces to explore the role of power, the ritual system, hierarchy, and other factors in the evolution of spatial form and function. This paper uses space syntax for the analysis of these two traditional Chinese palaces, which not only expands the research object of spatial syntax and clarifies the spatial characteristics of ancient Chinese palace buildings but can also inform the design of similar modern group buildings.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison between the Two Palaces

In the office space, as shown in

Figure 7a, the average depth of the emperor’s three main office spaces in the Beijing Forbidden City (BOS-(1–3)) was 8 (the average integration value was 0.96), while the average depth of the emperor’s two main office spaces (SOS-2 and SOS-5) in the Shenyang Imperial Palace was 2.5 (the average integration value was 1.11). These results indicated that the emperor’s office space in the Forbidden City was relatively enclosed, while the emperor’s office space in the Shenyang Imperial Palace had a relatively high level of accessibility. This might be because the layout of the Beijing Forbidden City was more complex and emphasized architectural hierarchy through a higher degree of enclosure. As the Shenyang Imperial Palace was an early palace, its layout was relatively simple, and the concept of hierarchy was not prominent; rather, convenient transportation and the equal relationship between the emperor’s office space and other spaces were emphasized. Previous studies have shown that the more centrally an object is placed within a defined space, the more it contributes to the overall segregation of that particular space. A building that is placed in the middle of a central square adds greater overall segregation to the neighborhood than the same building that is placed at the edge of the square [

12]. From this perspective, compared to the Shenyang Imperial Palace, the emperor’s three main office spaces in the Forbidden City in Beijing were located more centrally, making a more prominent contribution to spatial segmentation.

In terms of the living space, as shown in

Figure 7b, in the Forbidden City, the average depth value of the emperor’s three main bedchambers (BLS-(1–3)) was 11.3 (with an average integration value of 0.94), while the average depth of the concubines’ bedchambers (BLS-(5–6)) was 12 (with an average integration value of 0.85). In the Shenyang Imperial Palace, the depths of the emperor’s main bedchamber (SLS-6) and the concubines’ bedchambers (SLS-(7–10)) were all 6 (the integration values were all 0.70), which were much lower than the values for the emperor’s three main bedchambers in the Forbidden City. These results indicate that the enclosure of the bedchambers in the Forbidden City was significantly higher than that of the corresponding bedchambers in the Shenyang Imperial Palace.

In addition, the integration value (accessibility) of the emperor’s bedchamber (SLS-6) was the same as that of the concubines’ bedchambers (SLS-(7–10)) in the Shenyang Imperial Palace, reflecting a strong level of equality. The concept of hierarchy in traditional Chinese Confucian culture was not reflected in these spaces in the Shenyang Imperial Palace. The average integration of the emperor’s bedchambers (BLS-(1–3)) was higher than that of the concubines’ bedchambers (BLS-(5–6)) in the Forbidden City, which suggests that their accessibility level was higher. These results indicate an obvious hierarchical concept between these spaces.

As shown in

Figure 7c, the average depth of the four recreation spaces in the Forbidden City was 10.8 (the average integration value was 0.94), while the average depth of the four recreation spaces in the Shenyang Imperial Palace was 8 (the average integration value was 0.63). Thus, the recreation space in the Forbidden City of Beijing had a higher degree of enclosure than the recreation space in the Shenyang Imperial Palace in terms of connection with external spaces and had greater accessibility, which showed that the internal transportation was more convenient.

The average depth and integration values between the various spaces of the two palaces are shown in

Figure 8. The degree of enclosure of the living space, the recreation space, and the office space presented a decreasing trend in sequence in the Forbidden City, while the level of accessibility showed little difference. In the Shenyang Imperial Palace, the degree of spatial enclosure of the recreation space, the living space, and the office space decreased, while the level of accessibility increased sequentially. In both palace groups, the office space had the lowest degree of enclosure, which was in line with its functional requirements. The entirety of the Forbidden City was built at the same time after unified planning sessions; thus, it is reasonable that the degree of spatial enclosure of the recreation space was lower than (accessibility was higher than) that of the living space, which necessitated relative privacy. The construction of the Shenyang Imperial Palace was divided into three phases and completed gradually. The level of importance of the recreation space was lower than that of the office and living spaces; thus, it was the last space to be built. There was a certain irrationality in the location setting, which led to the degree of spatial enclosure of the recreation space being higher than that of the living space (the level of accessibility being lower than that of the living space).

4.2. Changes in Spatial Organization and Function

Social structuring with an unfixed rank is a method of studying political organization [

27]. There is a connection between space and power levels; thus, previous research has attempted to understand both power levels in the context of space [

28,

29] and how spatial organizational practices have shaped the essence of political levels in architecture [

30,

31]. In the two Chinese traditional palace groups that emphasized imperial power, the development and changes of these spatial organizations and functions should therefore be considered.

(1) Historically, the function of many spaces in the Forbidden City changed. For example, in the late Qing dynasty, the emperor moved his bedchambers from the original palaces (BLS-(1–3)) to BLS-4 (the depth value decreased from 11.3 to 10, while the integration value increased from 0.94 to 1.00). The spatial enclosure and accessibility changed slightly. At the same time, the most important office space for the main ministers was transferred from BOS-6 to BOS-7 (while the depth was unchanged, the integration increased from 0.65 to 1.23). The original office space group of BOS-(1–3) used by the emperor and BOS-6 used by the ministers was shifted backward as a whole to form a new “administrative power center” dominated by BLS-4 and BOS-7. This change improved the accessibility of the ministers’ office space and strengthened the connection between the emperor’s living space and the ministers’ office space, which could have improved the emperor’s efficiency in handling government affairs. However, it could also have placed the emperor and ministers farther from the external environment, which might have led to a decrease in the importance attached by the rulers to the people.

In the Shenyang Imperial Palace, when the emperor’s office spaces were transferred from the East Road to the Middle Road, the average depth increased from 2 to 2.8 and the spatial enclosure was enhanced. These changes were conducive to the formation of a sense of imperial authority and dignity. At the same time, the average integration value increased from 1.03 to 1.30, the level of accessibility improved, and internal transportation connections became more convenient. In terms of increasing integration values, the conversion of office space for emperors in the Shenyang Imperial Palace was similar to the conversion of office space for emperors and ministers in the Forbidden City of Beijing, which was also very similar to the conversion of the royal office space in Seoul in the seventeenth century. The new site of the top administrative headquarters of the Joseon Dynasty, that is, the king’s palaces and government headquarters, was placed in the site that had integration values higher than those for other areas [

32].

(2) The construction sequence of the Shenyang Imperial Palace was East Road, then Middle Road, and finally West Road. The average depth values of the East Road, Middle Road, and West Road palaces were 2, 5.1 and 8, respectively, while the average integration values were 1.03, 0.88, and 0.63, respectively, indicating that the degree of spatial enclosure of the three groups gradually increased and the accessibility level gradually decreased according to the construction period.

The earliest East Road palace buildings were all office buildings, and the integration values of SOS-(6–15) and SOS-5 were all 1.03. There was no distinction with regard to accessibility, and the space reflected equality. This was likely because before the establishment of the Qing dynasty in 1644, the Manchu regime was composed of various tribes without any thought or consciousness of imperial supremacy; thus, there was no strict hierarchical concept in the architectural space. Therefore, the East Road buildings had the greatest level of accessibility and the greatest amount of open space. In the subsequent construction of the Middle Road palaces, the office space in the south and the living space in the north were symmetrically distributed around the axes formed by SOS-1, SOS-2, SLS-5, and SLS-6, which was in line with the traditional Chinese courtyard layout. The average accessibility value of the Middle Road palaces decreased compared to the East Road palaces. The last construction of the west road building was the least accessible, which was the same as the phased construction of some traditional Chinese villages, and the last construction house for non-primary surname and non-major surname families was often distributed in areas with poor accessibility [

14].

4.3. Comparison between Traditional Chinese Palaces and Western Palaces

In the Forbidden City and Shenyang Imperial Palace, the office space was generally located near the main entrance of the palace groups in the south, while the living space was located in the north. The accessibility of the office space was higher than that of the living space. The Topkapu Palace in the Ottoman Empire also had a spatial pattern similar to that of “office space in the front and living space in the rear”. This palace placed the center of accessibility in the front office space. However, the spatial development of the Topkapu Palace differed from that of Chinese palaces in regard to improving the accessibility of the backyard and strengthening the rights of women [

33]. In three palaces built at different locations in three stages of Herod’s empire, the average depth of the palace built in the first stage was between 4 and 5. The king placed great emphasis on the status of the royal family and had limited contact with outside visitors. The average depth of the palace built in the second stage was reduced to between 2 and 3, which strengthened the level of communication and interaction between the king and officials. Finally, the average depth of the palace in the third stage increased to between 6 and 7, reemphasizing the uniqueness of the king’s space [

21]. These depth changes repeated in different stages did not appear in the development of the two above-mentioned Chinese palaces. In addition, Algeria’s Khdewedj El Amia Palace had an open gallery space, or “sqifa”, which divided the palace into internal and external parts, giving the interior space strong control over the entry of outside visitors [

34]. In this respect, the methods used in the Forbidden City were similar, as shown in

Figure 1b and

Figure 5. Qianqingmen Square, with a high integration value (1.4952), was used to separate the office space from the living space, thus reducing the accessibility of the living space. Additionally, using space syntax, an analysis of the Palace at Gede in Kenya showed that its rooms were organized in seven levels of depth [

17,

18], while there were 19 levels of depth in the Beijing Forbidden City and 9 levels of depth in the Shenyang Imperial Palace. Generally, the greater the level of depth of space, the stronger the enclosure of the space and the weaker the external connectivity. This indicates that the two palaces in China, especially the Beijing Forbidden City, have significantly higher spatial enclosures than the Palace at Gede.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the spatial features of the Beijing Forbidden City and the Shenyang Imperial Palace by using the relational diagram approach of the space syntax method. First, the depth value and integration value of each space were calculated by means of diagrams. Then, the results were compared and analyzed to reveal the similarities and differences among the office space, the living space, and the recreation space in these two palaces in terms of spatial enclosure and accessibility, as well as to reveal possible underlying reasons for these similarities and differences. The specific conclusions are as follows.

- (1)

The space settings in the Beijing Forbidden City and the Shenyang Imperial Palace were basically in line with the requirements of the spatial functions of these areas. The office space had the lowest degree of spatial enclosure, while the living space and the recreation space had relatively high degrees of enclosure. This layout was conducive to improving the convenience of using the office space and protecting the personal privacy of the emperor and his relatives.

- (2)

The historical status and construction background of the two palaces caused differences in the spatial features. A comparison of the same functional spaces in the two palaces showed that the office space in the Beijing Forbidden City was more enclosed than that in the Shenyang Imperial Palace, while the office space in the Shenyang Imperial Palace was more accessible than that in the Beijing Forbidden City. The spatial enclosure and accessibility of the emperor’s bedchambers were significantly higher in the Forbidden City than in the Shenyang Imperial Palace, while the accessibility of the recreation space was significantly lower in the Shenyang Imperial Palace than in the Forbidden City.

- (3)

Factors such as construction sequence and functional conversion during the use process also affected the rationality of the spatial layout of the two palaces. The construction of the Shenyang Imperial Palace was gradually completed in three phases. The recreation space was the last to be built, and its location was somewhat unreasonable, resulting in the spatial enclosure of the recreation space being higher than (accessibility being lower than) the living space. In the process of using Beijing Forbidden City, the transfer of functional space improved the accessibility of the office space, facilitated the connection between the emperor’s living space and the ministers’ office space, and improved the emperor’s efficiency in handling government affairs. Compared with traditional palaces in other countries, the various spaces found in the two Chinese palaces embodied a more pronounced sense of imperial power and ritual hierarchy.

The results of this paper have implications for the contemporary design of group combination buildings with different functions. First, the space syntax can be considered to calculate the degree of integration and depth values of different types of buildings in the architectural scheme stage, compare these values with building functions, and adjust the location of individual buildings accordingly. Second, in the process of functional adjustment between different buildings in the existing building group, the method of space syntax can also be used to analyze and determine whether the adjustment is reasonable. Finally, with the help of the model relationship diagram of space, it can avoid the unreasonable location of a single building due to phased construction and other reasons. In addition, by studying the spatial characteristics of these two traditional palace groups, this paper found that the scale of the building group should be accounted for in the process of building the J-graph using space syntax. If the spatial scale of the building group is large and there are many single buildings, the model relationship diagram should not be overly complicated or cumbersome. Otherwise, it might have a negative impact on the analysis of the relationship between different functional spaces.