A Systematic Review of Intracellular Microorganisms within Acanthamoeba to Understand Potential Impact for Infection

Abstract

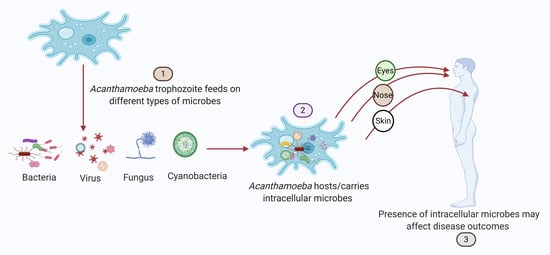

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Results of the Search

2.2. Included Studies

2.3. Laboratory Techniques Used for the Isolation and Identification of Intracellular Microbes in Acanthamoeba spp.

2.4. Culture Techniques Used to Isolate and Identify Acanthamoeba

2.5. Species and Genotypes of Acanthamoeba spp.

2.6. The Types of Microorganisms Commonly Found Inside Acanthamoeba spp.

2.7. Differences between the Intracellular Prokaryotes Found in Environmental and Clinical Isolates of Acanthamoeba

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Search Strategy and Data Sources

4.2. Inclusion Criteria

4.3. Exclusion Criteria

4.4. Data Abstraction, Quality Assessment, and Appraise Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

4.5. Outcome Measurements

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARMs | Amoeba-resistant microorganisms |

| ARB | Amoeba-resistant bacteria |

| CPE | Cytopathic effect |

| FLA | Free living amoeba |

| HAdV | Human adenovirus |

| PYG | Peptone-yeast-glucose medium |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| MATE | Multidrug and toxin extrusion |

| MBP | Mannose-binding protein |

| NOS | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

| NNA | Non-nutrient agar |

| NTM | Nontuberculous Mycobacterium |

| PYG | Peptone-yeast-glucose |

| SCGYE | Serum-casein glucose yeast extract |

| TSB | Tryptic soy-yeast extract broth |

| VBMC | Viable but non-culturable |

| WoS | Web of Science |

References

- Neelam, S.; Niederkorn, J.Y. Pathobiology and immunobiology of Acanthamoeba keratitis: Insights from animal models. Yale J. Biol. 2017, 90, 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt, P.; Degorge, S.; Saint-Jean, C.; Year, H.; Zekhnini, F.; Batellier, L.; Laroche, L.; Chaumeil, C. Resistance of Acanthamoeba to classic DNA extraction methods used for the diagnosis of corneal infections. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 92, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Torno, M.S., Jr.; Babapour, R.; Gurevitch, A.; Witt, M.D. Cutaneous acanthamoebiasis in AIDS. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000, 42, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunand, V.A.; Hammer, S.M.; Rossi, R.; Poulin, M.; Mary, A.; Doweiko, J.P.; DeGirolami, P.C.; Coakley, E.; Piessens, E.; Wanke, C.A. Parasitic sinusitis and otitis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: Report of five cases and review. J Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997, 25, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayamajhee, B.; Subedi, D.; Won, S.; Kim, J.J.Y.; Vijay, A.; Tan, J.; Henriquez, F.L.; Willcox, M.; Carnt, N.A.J.W. Investigating Domestic Shower Settings as a Risk Factor for Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Water 2020, 12, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, L.R.; Raphael, S.A.; Deutsch, E.S.; Johal, J.; Martyn, L.J.; Visvesvara, G.S.; Lischner, H.W. Disseminated Acanthamoeba infection in a child with symptomatic human immunodeficiency virus infection. Paediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1992, 11, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvesvara, G.S.; Moura, H.; Schuster, F.L. Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebae: Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia diploidea. FEMS. Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 50, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuster, F.L. Cultivation of pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebas. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 15, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases (DFWED). Parasites—Acanthamoeba—Granulomatous Amoebic Encephalitis (GAE); Keratitis. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/acanthamoeba/pathogen.html (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Siddiqui, R.; Khan, N.A. Biology and pathogenesis of Acanthamoeba. Parasites Vectors 2012, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xuan, Y.; Shen, Y.; Ge, Y.; Yan, G.; Zheng, S. Isolation and identification of Acanthamoeba strains from soil and tap water in Yanji, China. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2017, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corsaro, D.; Walochnik, J.; Köhsler, M.; Rott, M.B. Acanthamoeba misidentification and multiple labels: Redefining genotypes T16, T19, and T20 and proposal for Acanthamoeba micheli sp. nov. (genotype T19). Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 2481–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Sun, S.; Zhao, J.; Xie, L.J. Genotyping of Acanthamoeba isolates and clinical characteristics of patients with Acanthamoeba keratitis in China. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 59, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taher, E.E.; Méabed, E.M.; Abdallah, I.; Wahed, W. Acanthamoeba keratitis in noncompliant soft contact lenses users: Genotyping and risk factors, a study from Cairo, Egypt. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano-Cabral, F.; Cabral, G. Acanthamoeba spp. as agents of disease in humans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16, 273–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henriquez, F.L.; Mooney, R.; Bandel, T.; Giammarini, E.; Zeroual, M.; Fiori, P.L.; Margarita, V.; Rappelli, P.; Dessì, D. Paradigms of protist/bacteria symbiosis affecting human health: Acanthamoeba species and Trichomonas vaginalis. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 3380. [Google Scholar]

- Scheid, P.; Schwarzenberger, R. Acanthamoeba spp. as vehicle and reservoir of adenoviruses. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 111, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimaraes, A.J.; Gomes, K.X.; Cortines, J.R.; Peralta, J.M.; Peralta, R.H. Acanthamoeba spp. as a universal host for pathogenic microorganisms: One bridge from environment to host virulence. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 193, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Lohan, A.J.; Liu, B.; Lagkouvardos, I.; Roy, S.; Zafar, N.; Bertelli, C.; Schilde, C.; Kianianmomeni, A.; Bürglin, T.R.; et al. Genome of Acanthamoeba castellanii highlights extensive lateral gene transfer and early evolution of tyrosine kinase signaling. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fritsche, T.; Gautom, R.; Seyedirashti, S.; Bergeron, D.; Lindquist, T.D. Occurrence of bacterial endosymbionts in Acanthamoeba spp. isolated from corneal and environmental specimens and contact lenses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993, 31, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iovieno, A.; Ledee, D.R.; Miller, D.; Alfonso, E.C. Detection of bacterial endosymbionts in clinical Acanthamoeba isolates. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 445–452.e443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müller, A.; Walochnik, J.; Wagner, M.; Schmitz-Esser, S. A clinical Acanthamoeba isolate harboring two distinct bacterial endosymbionts. Eur. J. Protistol. 2016, 56, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchner, P. Endosymbiosis of Animals with Plant Microorganisms; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Scheid, P. Relevance of free-living amoebae as hosts for phylogenetically diverse microorganisms. Parasitol. Res. 2014, 113, 2407–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheid, P.; Hauröder, B.; Michel, R. Investigations of an extraordinary endocytobiont in Acanthamoeba sp.: Development and replication. Parasitol. Res. 2010, 106, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German, N.; Doyscher, D.; Rensing, C. Bacterial killing in macrophages and amoeba: Do they all use a brass dagger? Future Microbiol. 2013, 8, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declerck, P.; Behets, J.; De Keersmaecker, B.; Ollevier, F. Receptor-mediated uptake of Legionella pneumophila by Acanthamoeba castellanii and Naegleria lovaniensis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 103, 2697–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matz, C.; Nouri, B.; McCarter, L.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Acquired type III secretion system determines environmental fitness of epidemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus in the interaction with bacterivorous protists. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, R.; Malik, H.; Sagheer, M.; Jung, S.-Y.; Khan, N.A. The type III secretion system is involved in Escherichia coli K1 interactions with Acanthamoeba. Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 128, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.-Y.; Matin, A.; Kim, K.S.; Khan, N.A. The capsule plays an important role in Escherichia coli K1 interactions with Acanthamoeba. Int. J. Parasitol. 2007, 37, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molmeret, M.; Horn, M.; Wagner, M.; Santic, M.; Kwaik, Y.A. Amoebae as training grounds for intracellular bacterial pathogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greub, G.; Raoult, D. Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmitz-Esser, S.; Toenshoff, E.R.; Haider, S.; Heinz, E.; Hoenninger, V.M.; Wagner, M.; Horn, M. Diversity of bacterial endosymbionts of environmental Acanthamoeba isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 5822–5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Espinoza-Vergara, G.; Hoque, M.M.; McDougald, D.; Noorian, P. The Impact of Protozoan Predation on the Pathogenicity of Vibrio cholerae. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maumus, F.; Blanc, G. Study of gene trafficking between Acanthamoeba and giant viruses suggests an undiscovered family of amoeba-infecting viruses. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 3351–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hervet, E.; Charpentier, X.; Vianney, A.; Lazzaroni, J.-C.; Gilbert, C.; Atlan, D.; Doublet, P. Protein kinase LegK2 is a type IV secretion system effector involved in endoplasmic reticulum recruitment and intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 1936–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomas, V.; McDonnell, G.; Denyer, S.P.; Maillard, J.-Y.J. Free-living amoebae and their intracellular pathogenic microorganisms: Risks for water quality. FEMS. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fritsche, T.R.; Sobek, D.; Gautom, R.K. Enhancement of in vitro cytopathogenicity by Acanthamoeba spp. following acquisition of bacterial endosymbionts. FEMS. Microbiol. Lett. 1998, 166, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bozue, J.A.; Johnson, W. Interaction of Legionella pneumophila with Acanthamoeba castellanii: Uptake by coiling phagocytosis and inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion. Infect. Immun. 1996, 64, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yagita, K.; Matias, R.; Yasuda, T.; Natividad, F.; Enriquez, G.; Endo, T. Acanthamoeba sp. from the Philippines: Electron microscopy studies on naturally occurring bacterial symbionts. Parasitol. Res. 1995, 81, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, D.I.; Kong, H.H.; Kim, T.H.; Hwang, M.Y.; Yu, H.S.; Yun, H.C.; Seol, S.Y. Bacterial endosymbiosis within the cytoplasm of Acanthamoeba lugdunensis isolated from a contact lens storage case. Korean J. Parasitol. 1997, 35, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, R.; Springer, N.; Schönhuber, W.; Ludwig, W.; Schmid, E.N.; Müller, K.; Michel, R. microbiology, e. Obligate intracellular bacterial parasites of acanthamoebae related to Chlamydia spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michel, R.; Hauröder, B. Isolation of an Acanthamoeba strain with intracellular Burkholderia pickettii infection. Int. J. Med Microbiol. 1997, 285, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, R.; Müller, K.-D.; Amann, R.; Schmid, E.N. Legionella-like slender rods multiplying within a strain of Acanthamoeba sp. isolated from drinking water. Parasitol. Res. 1997, 84, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, R.; Michel, R.; Muller, K.-D.; Schmid, E.N. Archaea like endocytobiotic organisms isolated from Acanthamoeba SP (GR II). Endocytobiosis Cell Res. 1998, 12, 185–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mölled, K.-D.; Schmid, E.N.; Michel, R. Intracellular Bacteria of Acanthamoebae Resembling Legionella spp. Turned Out to be Cytophaga sp. Int. J. Med Microbiol. 1999, 289, 389–397. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, M.; Fritsche, T.R.; Gautom, R.K.; Schleifer, K.H.; Wagner, M. Novel bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba spp. related to the Paramecium caudatum symbiont Caedibacter caryophilus. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 1, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, T.R.; Horn, M.; Seyedirashti, S.; Gautom, R.K.; Schleifer, K.-H.; Wagner, M. In situ detection of novel bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba spp. phylogenetically related to members of the order Rickettsiales. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fritsche, T.R.; Horn, M.; Wagner, M.; Herwig, R.P.; Schleifer, K.-H.; Gautom, R.K. Phylogenetic diversity among geographically dispersed Chlamydiales endosymbionts recovered from clinical and environmental isolates of Acanthamoeba spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 2613–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collingro, A.; Toenshoff, E.R.; Taylor, M.W.; Fritsche, T.R.; Wagner, M.; Horn, M. ‘Candidatus Protochlamydia amoebophila’, an endosymbiont of Acanthamoeba spp. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1863–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtles, R.; Rowbotham, T.; Michel, R.; Pitcher, D.; Lascola, B.; Alexiou-Daniel, S.; Raoult, D. ‘Candidatus Odyssella thessalonicensis’ gen. nov., sp. nov., an obligate intracellular parasite of Acanthamoeba species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000, 50, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horn, M.; Harzenetter, M.D.; Linner, T.; Schmid, E.N.; Müller, K.D.; Michel, R.; Wagner, M. Members of the Cytophaga–Flavobacterium–Bacteroides phylum as intracellular bacteria of acanthamoebae: Proposal of ‘Candidatus Amoebophilus asiaticus’. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 3, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, M.; Fritsche, T.R.; Linner, T.; Gautom, R.K.; Harzenetter, M.D.; Wagner, M. Obligate bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba spp. related to the beta-Proteobacteria: Proposal of ’Candidatus Procabacter acanthamoebae’gen. nov., sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Scola, B.; Audic, S.; Robert, C.; Jungang, L.; de Lamballerie, X.; Drancourt, M.; Birtles, R.; Claverie, J.-M.; Raoult, D. A giant virus in amoebae. Science 2003, 299, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.S.; Jeong, H.J.; Hong, Y.-C.; Seol, S.-Y.; Chung, D.-I.; Kong, H.H. Natural occurrence of Mycobacterium as an endosymbiont of Acanthamoeba isolated from a contact lens storage case. Korean J. Parasitol. 2007, 45, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, Y.-H.; Yu, H.S.; Jeong, H.J.; Seol, S.-Y.; Chung, D.-I.; Kong, H.H. Molecular characterization of bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba isolates from infected corneas of Korean patients. Korean J. Parasitol. 2007, 45, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, E.; Kolarov, I.; Kästner, C.; Toenshoff, E.R.; Wagner, M.; Horn, M. An Acanthamoeba sp. containing two phylogenetically different bacterial endosymbionts. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1604–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorenzo-Morales, J.; Coronado-Álvarez, N.; Martínez-Carretero, E.; Maciver, S.K.; Valladares, B. Detection of four adenovirus serotypes within water-isolated strains of Acanthamoeba in the Canary Islands, Spain. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 77, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheid, P.; Zöller, L.; Pressmar, S.; Richard, G.; Michel, R. An extraordinary endocytobiont in Acanthamoeba sp. isolated from a patient with keratitis. Parasitol. Res. 2008, 102, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antwerpen, M.; Georgi, E.; Zoeller, L.; Woelfel, R.; Stoecker, K.; Scheid, P. Whole-genome sequencing of a pandoravirus isolated from keratitis-inducing acanthamoeba. Genome Announc. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, S.H.; Cho, M.K.; Ahn, S.C.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, D.-H.; Xuan, Y.-H.; Hong, Y.C.; Kong, H.H.; Chung, D.I.; et al. Endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba isolated from domestic tap water in Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2009, 47, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, J.; Kawaguchi, K.; Nakamura, S.; Hayashi, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Takahashi, K.; Mizutani, Y.; Yao, T.; Yamaguchi, H. Survival and transfer ability of phylogenetically diverse bacterial endosymbionts in environmental Acanthamoeba isolates. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2010, 2, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okude, M.; Matsuo, J.; Nakamura, S.; Kawaguchi, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Sakai, H.; Yoshida, M.; Takahashi, K.; Yamaguchi, H. Environmental chlamydiae alter the growth speed and motility of host acanthamoebae. Microbes Environ. 2012, 27, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Corsaro, D.; Pages, G.S.; Catalan, V.; Loret, J.-F.; Greub, G. Biodiversity of amoebae and amoeba-associated bacteria in water treatment plants. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2010, 213, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, G.; Hoffart, L.; La Scola, B.; Raoult, D.; Drancourt, M. Ameba-associated keratitis, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, K.C.; Hetrick, N.D.; Molestina, R.E. Evidence for a Previously Unrecognized Mycobacterial Endosymbiont in Acanthamoeba castellanii Strain Ma (ATCC® 50370™). J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2011, 58, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaze, W.H.; Morgan, G.; Zhang, L.; Wellington, E.M. Mimivirus-like particles in acanthamoebae from Sewage Sludge. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsaro, D.; Müller, K.-D.; Michel, R. Molecular characterization and ultrastructure of a new amoeba endoparasite belonging to the Stenotrophomonas maltophilia complex. Exp. Parasitol. 2013, 133, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampo, A.; Matsuo, J.; Yamane, C.; Yagita, K.; Nakamura, S.; Shouji, N.; Hayashi, Y.; Yamazaki, T.; Yoshida, M.; Kobayashi, M.; et al. High-temperature adapted primitive Protochlamydia found in Acanthamoeba isolated from a hot spring can grow in immortalized human epithelial HEp-2 cells. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagkouvardos, I.; Shen, J.; Horn, M. Improved axenization method reveals complexity of symbiotic associations between bacteria and acanthamoebae. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2014, 6, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschio, V.J.; Corção, G.; Bücker, F.; Caumo, K.; Rott, M.B. Identification of Paenibacillus as a Symbiont in Acanthamoeba. Curr. Microbiol. 2015, 71, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José Maschio, V.; Corção, G.; Rott, M.B. Identification of Pseudomonas spp. as amoeba-resistant microorganisms in isolates of Acanthamoeba. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 2015, 57, 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, H.; Hattori, T.; Koike, N.; Ehara, T.; Fujita, K.; Takahashi, H.; Kumakura, S.; Kuroda, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Goto, H. Investigation of the role of bacteria in the development of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea 2015, 34, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyyati, M.; Mahyar, M.; Haghighi, A.; Vala, M.H. Occurrence of Potentially Pathogenic Bacterial-Endosymbionts in Acanthamoeba spp. J. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2015, 10, 181. [Google Scholar]

- Magnet, A.; Peralta, R.; Gomes, T.; Izquierdo, F.; Fernandez-Vadillo, C.; Galvan, A.; Pozuelo, M.; Pelaz, C.; Fenoy, S.; Del Águila, C. Vectorial role of Acanthamoeba in Legionella propagation in water for human use. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 505, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukumoto, T.; Matsuo, J.; Okubo, T.; Nakamura, S.; Miyamoto, K.; Oka, K.; Takahashi, M.; Akizawa, K.; Shibuya, H.; Shimizu, C.; et al. Acanthamoeba containing endosymbiotic chlamydia isolated from hospital environments and its potential role in inflammatory exacerbation. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheikl, U.; Tsao, H.-F.; Horn, M.; Indra, A.; Walochnik, J. Free-living amoebae and their associated bacteria in Austrian cooling towers: A 1-year routine screening. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 3365–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Purssell, A.; Lau, R.; Boggild, A.K. Azithromycin and doxycycline attenuation of Acanthamoeba virulence in a human corneal tissue model. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 1303–1311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Faizah, M.; Anisah, N.; Yusof, S.; Noraina, A.; Adibah, M.R. Molecular detection of bacterial endosymbionts in Acanthamoeba spp.: A preliminary study. Med Health 2017, 12, 286–292. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, L.L.; Mak, J.W.; Ambu, S.; Chong, P.Y. Identification and ultrastructural characterization of Acanthamoeba bacterial endocytobionts belonging to the Alphaproteobacteria class. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hajialilo, E.; Rezaeian, M.; Niyyati, M.; Pourmand, M.R.; Mohebali, M.; Norouzi, M.; Pashabeyg, K.R.; Rezaie, S.; Khodavaisy, S. Molecular characterization of bacterial, viral and fungal endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba isolates in keratitis patients of Iran. Exp. Parasitol. 2019, 200, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, T.; Barnes, W.G.; Meyers, D. Axenic cultivation of large populations of Acanthamoeba castellanii (JBM). J. Parasitol. 1970, 56, 904–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, J.; Alfieri, S.C. Growth, encystment and survival of Acanthamoeba castellanii grazing on different bacteria. FEMS. Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 66, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lacerda, A.G.; Lira, M. Acanthamoeba keratitis: A review of biology, pathophysiology and epidemiology. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2021, 41, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, R.J. Mechanisms of purifying amoebae by migration on agar surfaces. J. Protozool. 1958, 5, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.J. Purification, axenic cultivation, and description of a soil amoeba, Acanthamoeba sp. J. Protozool. 1957, 4, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyyati, M.; Abedkhojasteh, H.; Salehi, M.; Farnia, S.; Rezaeian, M. Axenic cultivation and pathogenic assays of acanthamoeba strains using physical parameters. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2013, 8, 186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.A. Acanthamoeba: Biology and increasing importance in human health. FEMS. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 30, 564–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilvington, S.; Larkin, D.; White, D.; Beeching, J.R. Laboratory investigation of Acanthamoeba keratitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990, 28, 2722–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eroğlu, F.; Evyapan, G.; Koltaş, İ.S. The cultivation of Acanthamoeba using with different axenic and monoxenic media. Middle Black Sea J. Health Sci. 2015, 1, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huws, S.A.; Morley, R.J.; Jones, M.V.; Brown, M.R.; Smith, A.W. Interactions of some common pathogenic bacteria with Acanthamoeba polyphaga. FEMS. Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 282, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Todd, C.D.; Reyes-Batlle, M.; Martín-Navarro, C.M.; Dorta-Gorrín, A.; López-Arencibia, A.; Martínez-Carretero, E.; Piñero, J.E.; Valladares, B.; Lindo, J.F.; Lorenzo-Morales, J. Isolation and genotyping of Acanthamoeba strains from soil sources from Jamaica, West Indies. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2015, 62, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnier, I.; Raoult, D.; La Scola, B. Isolation and identification of amoeba-resisting bacteria from water in human environment by using an Acanthamoeba polyphaga co-culture procedure. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collingro, A.; Poppert, S.; Heinz, E.; Schmitz-Esser, S.; Essig, A.; Schweikert, M.; Wagner, M.; Horn, M. Recovery of an environmental chlamydia strain from activated sludge by co-cultivation with Acanthamoeba sp. Microbiology 2005, 151, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, V.; Casson, N.; Greub, G. Criblamydia sequanensis, a new intracellular Chlamydiales isolated from Seine river water using amoebal co-culture. J. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 8, 2125–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Abd, H.; Edvinsson, B.; Sandström, G. Acanthamoeba castellanii an environmental host for Shigella dysenteriae and Shigella sonnei. Arch. Microbiol. 2009, 191, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson-Olsson, D.; Waldenström, J.; Broman, T.; Olsen, B.; Holmberg, M. Protozoan Acanthamoeba polyphaga as a potential reservoir for Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Steinert, M.; Emödy, L.; Amann, R.; Hacker, J.; Microbiology, E. Resuscitation of viable but nonculturable Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia JR32 by Acanthamoeba castellanii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 2047–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Axelsson-Olsson, D.; Ellström, P.; Waldenström, J.; Haemig, P.D.; Brudin, L.; Olsen, B. Acanthamoeba-Campylobacter coculture as a novel method for enrichment of Campylobacter species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 6864–6869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dey, R.; Rieger, A.M.; Stephens, C.; Ashbolt, N.J. Interactions of pseudomonas aeruginosa with Acanthamoeba polyphaga observed by imaging flow cytometry. Cytom. A 2019, 95, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd, H.; Johansson, T.; Golovliov, I.; Sandström, G.; Forsman, M. Survival and growth of Francisella tularensis in Acanthamoeba castellanii. J Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van der Henst, C.; Scrignari, T.; Maclachlan, C.; Blokesch, M. An intracellular replication niche for Vibrio cholerae in the amoeba Acanthamoeba castellanii. ISME J. 2016, 10, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Etr, S.H.; Margolis, J.J.; Monack, D.; Robison, R.A.; Cohen, M.; Moore, E.; Rasley, A. Francisella tularensis type A strains cause the rapid encystment of Acanthamoeba castellanii and survive in amoebal cysts for three weeks postinfection. J. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7488–7500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hojo, F.; Osaki, T.; Yonezawa, H.; Hanawa, T.; Kurata, S.; Kamiya, S. Acanthamoeba castellanii supports extracellular survival of Helicobacter pylori in co-culture. J. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 26, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.; Hoffman, P.S.; Glomski, I.J. Germination and amplification of anthrax spores by soil-dwelling amoebas. J. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 8075–8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Steenbergen, J.N.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Malliaris, S.D.; Casadevall, A. Interaction of Blastomyces dermatitidis, Sporothrix schenckii, and Histoplasma capsulatum with Acanthamoeba castellanii. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 3478–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Steenbergen, J.; Shuman, H.; Casadevall, A. Cryptococcus neoformans interactions with amoebae suggest an explanation for its virulence and intracellular pathogenic strategy in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 15245–15250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunes, T.E.T.; Brazil, N.T.; Fuentefria, A.M.; Rott, M.B. Acanthamoeba and Fusarium interactions: A possible problem in keratitis. Acta Trop. 2016, 157, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattana, A.; Serra, C.; Mariotti, E.; Delogu, G.; Fiori, P.L.; Cappuccinelli, P. Acanthamoeba castellanii promotion of in vitro survival and transmission of coxsackie b3 viruses. Eukaryot. Cell 2006, 5, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Matsuo, J.; Yamazaki, T.; Ishida, K.; Yagita, K. Draft genome sequence of high-temperature-adapted Protochlamydia sp. HS-T3, an amoebal endosymbiotic bacterium found in Acanthamoeba Isolated from a hot spring in Japan. Genome Announc. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, M. Complete genome sequence of the endosymbiont of Acanthamoeba strain UWC8, an amoeba endosymbiont belonging to the “Candidatus Midichloriaceae” family in Rickettsiales. Genome Announc. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsia, Y.C.; Leal, S.M., Jr.; Booton, G.C.; Joslin, C.E.; Cianciotto, N.P.; Tu, E.Y.; Pearlman, E. Acanthamoeba Keratitis Is Exacerbated In The Presence Of Intracellular Legionella Pneumophila. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 5794. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, S.P.; Sriram, R.; Qvarnstrom, Y.; Roy, S.; Verani, J.; Yoder, J.; Lorick, S.; Roberts, J.; Beach, M.J.; Visvesvara, G. Resistance of Acanthamoeba cysts to disinfection in multiple contact lens solutions. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 2040–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verani, J.R.; Lorick, S.A.; Yoder, J.S.; Beach, M.J.; Braden, C.R.; Roberts, J.M.; Conover, C.S.; Chen, S.; McConnell, K.A.; Chang, D.C.; et al. National outbreak of Acanthamoeba keratitis associated with use of a contact lens solution, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnt, N.; Hoffman, J.J.; Verma, S.; Hau, S.; Radford, C.F.; Minassian, D.C.; Dart, J.K. Acanthamoeba keratitis: Confirmation of the UK outbreak and a prospective case-control study identifying contributing risk factors. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheikl, U.; Sommer, R.; Kirschner, A.; Rameder, A.; Schrammel, B.; Zweimüller, I.; Wesner, W.; Hinker, M.; Walochnik, J. Free-living amoebae (FLA) co-occurring with legionellae in industrial waters. Eur. J. Protistol. 2014, 50, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albert-Weissenberger, C.; Cazalet, C.; Buchrieser, C. Legionella pneumophila—A human pathogen that co-evolved with freshwater protozoa. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.; Brown, M.R.W. Trojan horses of the microbial world: Protozoa and the survival of bacterial pathogens in the environment. Microbiology 1994, 140, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koltas, I.S.; Eroglu, F.; Erdem, E.; Yagmur, M.; Tanır, F. The role of domestic tap water on Acanthamoeba keratitis in non-contact lens wearers and validation of laboratory methods. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 3283–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, A.B.; Richdale, K.; Mitchell, G.L.; Kinoshita, B.T.; Lam, D.Y.; Wagner, H.; Sorbara, L.; Chalmers, R.L.; Collier, S.A.; Cope, J.R. Water exposure is a common risk behavior among soft and gas-permeable contact lens wearers. Cornea 2017, 36, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilvington, S.; Gray, T.; Dart, J.; Morlet, N.; Beeching, J.R.; Frazer, D.G.; Matheson, M. Acanthamoeba keratitis: The role of domestic tap water contamination in the United Kingdom. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeong, H.J.; Yu, H.S. The role of domestic tap water in Acanthamoeba contamination in contact lens storage cases in Korea. Korean J. Parasitol. 2005, 43, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mura, M.; Bull, T.J.; Evans, H.; Sidi-Boumedine, K.; McMinn, L.; Rhodes, G.; Pickup, R.; Hermon-Taylor, J. Replication and long-term persistence of bovine and human strains of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis within Acanthamoeba polyphaga. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berk, S.G.; Ting, R.S.; Turner, G.W.; Ashburn, R.J.; Microbiology, E. Production of Respirable Vesicles Containing LiveLegionella pneumophila Cells by Two Acanthamoeba spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chekabab, S.M.; Daigle, F.; Charette, S.J.; Dozois, C.M.; Harel, J. Shiga toxins decrease enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli survival within Acanthamoeba castellanii. FEMS. Microbiol. Letters. 2013, 344, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmitz-Esser, S.; Linka, N.; Collingro, A.; Beier, C.L.; Neuhaus, H.E.; Wagner, M.; Horn, M. ATP/ADP translocases: A common feature of obligate intracellular amoebal symbionts related to Chlamydiae and Rickettsiae. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Siddiqui, R.; Khan, N.A. War of the microbial worlds: Who is the beneficiary in Acanthamoeba–bacterial interactions? Exp. Parasitol. 2012, 130, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, G.; Shuman, H.A. Legionella pneumophila utilizes the same genes to multiply within Acanthamoeba castellanii and human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 2117–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Best, A.; Price, C.; Ozanic, M.; Santic, M.; Jones, S.; Kwaik, Y.A. A Legionella pneumophila amylase is essential for intracellular replication in human macrophages and amoebae. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, H.; La Scola, B.; Audic, S.; Renesto, P.; Blanc, G.; Robert, C.; Fournier, P.-E.; Claverie, J.-M.; Raoult, D. Genome sequence of Rickettsia bellii illuminates the role of amoebae in gene exchanges between intracellular pathogens. PLoS Genet. 2006, 2, e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. J. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Ye, C.; Liao, L.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Deng, C.; Liu, L. Adjuvant β-lactam therapy combined with vancomycin or daptomycin for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country, Date of Study | Analysed Sample (Clinical/Environmental) | Laboratory Investigation | Positive Samples for Intracellular Microbes | Species and Genotypes of Acanthamoeba | Identified Intracellular Microbes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA, 1993 [20] | Clinical (corneal-19, and contact lens-4), environmental specimens (soil, forest detritus, lake and stream sediments, pond water, tree bark, potting soil, 25), and ATCC strains (9) | Culture, electron microscopy, staining | 14 of 57 | ATCC strains: A. culbertsoni 30886, 30011, and 30868 A. rhysodes 30973, A. polyphaga 30871 and 30461 A. astronyxis 30137, A. hatchetti 30730, A. palestinensis 30870, Acanthamoeba strain 30173 | Gram-negative rods and cocci and non-acid fast non-motile bacteria |

| Philippines, 1995 [40] | Pond | Culture, PCR, electronic microscopy | 1 of 1 | Acanthamoeba sps | Gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria, 1.3 × 0.43 µm in size |

| South Korea, 1997 [41] | Contact lens storage | PCR, TEM | 1 of 1 | A. lugdunesis | Rod-shaped bacteria, 1.38 × 0.5µm in size |

| Germany, 1997 [42] | Nasal mucosa of humans | Culture, electron microscopy, in situ hybridization | 2 of 2 | Acanthamoeba spp. and A. mauritaniensis | Coccoid shaped related to Chlamydia spp.; Ca. Parachlamydia acanthamoebae (proposed name for strain Bn9) |

| Germany, 1997 [43] | Wet area of a physiotherapy unit | Culture, light, and electron microscopy, biochemical tests | 1 of 2 | Acanthamoeba spp. Group II | Burkholderia pickettii (biovar 2) |

| Germany, 1998 [44] | Cold water tap of a hospital plumbing system | Culture, electron microscopy, gas-liquid chromatography | 1 of 1 | Acanthamoeba spp. Group II (K62) | Legionella-like slender rods |

| Germany, 1998 [45] | Potable water reservoir | Culture, electron microscopy | 1 of 1 | Acanthamoeba sps Group II | Archaea like (short rod shaped, 1–1.5 μm length) endoparasite |

| Germany, 1999 [46] | Drinking water system of a hospital | Culture, phase contrast and electron microscopy, gas-liquid chromatography, Gram staining, biochemical tests | 1 of 1 | Acanthamoeba spp. Group II | Cytophaga spp. (K69i) |

| Germany, 1999 [47] | Two clinical isolates (HN-3 and UWC9) and one environmental isolate (UWE39) | Culture, PCR, Gram and Giemsa staining, sequencing, electron microscopy, FISH, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) | 3 of 3 | Acanthamoeba spp. (UWC9 and UWE39); A. polyphaga (HN-3) [20] | Ca. Caedibacter acanthamoebae (proposed name); Ca. Paracaedibacter acanthamoebae (proposed name); Ca. Paracaedibacter symbiosus (proposed name) |

| USA, 1999 [48] | Corneal scraping | Culture, Gram and Giemsa staining, confocal laser-scanning microscopy, PCR amplification, sequencing of 16S rRNA gene, EM | 2 of 2 | Acanthamoeba species (UWC8 and UWC36) | Phylogenetically related to members of the order Rickettsiales branch of the alpha subdivision of the Proteobacteria (99.6% sequence similarity to each other), Ca. Midichloriaceae family in Rickettsiales |

| USA, 2000 [49] | Clinical (corneal tissues—1), and environmental isolates (soil samples from the USA—1, and sewage sludge from Germany—1) | Culture, Giemsa staining, FISH, electron microscopy, PCR, sequencing | 4 of 4 | Acanthamoeba spp. | Gram-negative cocci, may represent distinct species of Parachlamydiaceae Ca. Protochlamydia amoebophila (UWE25) [50] |

| Greece, 2000 [51] | Water sample collected from the drip-tray of the air conditioning unit of a hospital | Culture, Gimenez Staining, microscopy, PCR, 16S rRNA sequencing | 1 of 1 | Acanthamoeba sps | Ca. Odyssella thessalonicensis’ gen. nov., sp. nov. [gram negative, rod, and motile] (proposed name); Note: The phylogenetic position, inferred from comparison of the 16S rRNA gene sequence, is within the α-Proteobacteria. |

| Germany, 2001 [52] | Drinking water in a hospital, corneal scrapings of a keratitis patients (Germany) and eutrophic lake sediment (Malaysia) | Culture, phase contrast and electron microscopy, PCR, 16S rRNA sequencing | 3 of 3 | Acanthamoeba spp. T4 | Flavobacterium succinicans (99% 16S rRNA sequence similarity) or Flavobacterium johnsoniae (98% 16S rRNA sequence similarity); Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides (CFB) phylum (<82% 16S rRNA sequence similarity); Ca. Amoebophilus asiaticus (proposed name) |

| Germany, 2002 [53] | Clinical and environmental isolates from the USA and Malaysia | Culture, Gram, Giemsa and DAPI staining, electron microscopy, FISH, PCR, 16S and 23S rDNA-based sequencing | 6 of 6 | A. polyphaga strain Page 23 and Acanthamoeba spp. | Rod-shaped Gram-negative obligate bacterial endosymbionts, related to the β-Proteobacteria: Ca. Procabacter acanthamoebae’ gen. nov., sp. nov. (proposed name) |

| France, 2003 [54] | Water of cooling tower | Gram staining, electronic microscopy, genome sequencing | 1 of 1 | A. polyphaga | Mimivirus |

| South Korea, 2007 [55] | Contact lens storage case | Culture, MtDNA RFLP analysis, TEM, PCR, sequencing, AFB, and fluorescent staining | 1 of 1 | A. lugdunensis | Mycobacterium spp. |

| South Korea, 2007 [56] | From the infected corneas of Korean patients | Culture, orcein staining, RFLP, TEM, PCR, sequence analysis of 16S rDNA of endosymbiontsand 18S rDNA of Acanthamoeba | 4 of 4 | Strains of Acanthamoeba spp. belonging to the A. castellanii complex T4 | Caedibacter caryophilus (proposed name); Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides (CFB) phylum |

| Austria, 2007 [57] | Lake | Culture, FISH, TEM, PCR, 16S rRNA sequences | 1 of 1 | Acanthamoeba sps T4 | Ca. procabacter sp. OEW1 (proposed name); Parachlamydia acanthamoebae Bn9 |

| Spain, 2007 [58] | Tap water samples | Culture, PCR | 34 of 236 | Acanthamoeba spp. T2; T3; T4; T6 and T7 | Human adenoviruses (HadV); serotypes HadV-1, 2, 8, and 37 |

| Germany, 2008 [59] | Contact lens and storage case fluid | Culture, light and electron microscopy | 1 of 1 | 1. A. triangularis 2. Not yet determined, with polygonal cysts | Pandoravirus inopinatum [60] |

| Austria, 2008 [33] | Soil and lake sediment samples from Austria, Tunisia, and Dominica (N=10) | Culture, TEM and confocal laser scanning microscopy, PCR, genotyping, sequencing | 8 of 10 | Acanthamoeba spp. (isolates EI1, EI2, EI3, 5a2, EIDS3, and EI6) = T4 and (isolates EI4 and EI5) = T2 | Parachlamydia sp. isolate Hall’s coccus; Protochlamydia amoebophila UWE25; Ca. Paracaedibacter acanthamoebae (proposed name); Ca. Amoebophilus asiaticus TUMSJ-321 (proposed name); Ca. Procabacter acanthamoebae Page23 (proposed name); Parachlamydia sp. isolate UV-7 |

| South Korea, 2009 [61] | Tap water | Culture, TEM and phase-contrast light microscopy, PCR, 16S r DNA sequencing | 5 of 17 | Acanthamoeba spp. | Ca. Amoebophilus asiaticus (proposed name); Ca. Odyssella thessalonicensis (α-Proteobacteria) (proposed name); Methylophilus spp. |

| Japan, 2010 [62] | Environmental samples (41 soil samples: 19 river water samples, 4 lake water samples and 2 pond water samples) | Culture, PCR, sequencing, FISH, TEM | 5 of 41 | Acanthamoeba spp. T2;T4; T6 and T13 | Rod-shaped belonging to α- and β-Proteobacteria phyla; sphere/crescent-shaped belonging to the order chlamydiales Protochlamydia; Neochlamydia [63] |

| USA, 2010 [21] | Acanthamoeba isolates (N=37) recovered from the cornea and contact lens paraphernalia of 23 patients, 1 environmental (water) isolate | Culture, PCR, sequencing, FISH, TEM | 22 of 38 | Acanthamoeba spp. | Legionella sp.; Pseudomonas sp.; Mycobacterium sp.; Chlamydia sp. |

| Spain, 2010 [64] | Three different water treatment plants | Axenic culture, sequencing a portion of the 18S rRNA gene for amoeba and specific 16S rRNA gene PCR for endosymbionts | 5 of 9 | Acanthamoeba T4 strain | Chlamydiae; Legionellae |

| France, 2011 [65] | Corneal scraping of AK patient, contact lens storage case liquid | Culture, slit-lamp examination, PCR, sequencing, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry | 1 of 1 | A. polyphaga | Ca. Babela massiliensis/ Deltaproteobacterium (proposed name); Alphaproteobacterium bacillus; mimivirus strain Lentille; virophage Sputnik 2 |

| USA, 2011 [66] | Eye infection, A. castellanii strain Ma (ATCC 50370), culture collection | Culture, light microscopy, PCR, sequencing | 1 of 1 | A. castellanii (ATCC 50370) | Species of Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) (M. timonense; M. marseillense and M. chimaera). |

| UK, 2011 [67] | Sewage sludge | Culture, PCR, sequencing of Amoeba only | 1 of 1 | A. palestinensis (22/25 clones) within the T6 clade | Mimivirus-like particles |

| Germany, 2013 [68] | From biofilm of a flushing cistern in a lavatory | Culture, PCR, sequencing, electron microscopy | 1 of 1 | Acanthamoeba spp. | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia complex (96.5% sequence similarity) |

| Japan, 2014 [69] | Hot Spring in Japan | Culture, FISH, TEM, confocal laser and phase-contrast microscopy, PCR, sequencing | 1 of 1 | Acanthamoeba spp. T5 | Protochlamydia |

| Austria, 2014 [70] | Three environmental samples | Axenic culture, PCR, FISH, sequencing | 7 of 10 | Acanthamoeba spp. (closely related to A. castellanii Neff GenBank Acc. U07416, A. polyphaga) | Paraceadibacter; Neochlamydia; Protochlamydia; Procabacter; Rickettsiales; Amoebophilus |

| Brazil, 2015 [71] | Seven samples from air-condition units, and five from contact lens cases | Culture, FISH, semi nested-PCR, DGGE, sequencing | 3 of 12 | Acanthamoeba spp. T3; T4 and T5 | Paenibacillus spp., Ca. Protochlamydia amoebophila, (uncultured γ-Proteobacterium) (prposed name) |

| Brazil, 2015 [72] | Seven samples from air-condition units, and five from contact lens cases | Axenic culture, conventional PCR, amplicon sequencing | 12 of 12 | Acanthamoeba spp. T3; T4 and T5 | Pseudomonas spp. |

| Japan, 2015 [73] | Isolated from a patient with AK | Culture, Gram staining, MicroScan autoSCAN-4 system, PCR | 1 of 1 | Acanthamoeba strain T4 | E. coli |

| Iran, 2015 [74] | Recreational water sources | Axenic culture, staining, PCR, genotyping, microscopy | 5 of 16 | Acanthamoeba spp. T4 and T5 | P. aeruginosa; Agrobacterium tumefaciens |

| Spain, 2015 [75] | Seventy water samples (three DWTP, three wastewater treatment plants and five natural pools) | Culture, PCR, genotyping, sequencing | 43 of 54 | Acanthamoeba T3, T4 and T11 | Legionella spp. |

| Japan, 2016 [76] | Smear samples from University Hospital | Culture, PCR, sequencing | 3 of 21 | Acanthamoeba spp. T4 | Protochlamydia spp.; Neochlamydia spp. |

| Austria, 2016 [22] | Corneal scraping of AK patient | Axenic culture, PCR, sequencing, FISH, TEM | 1 of 1 | A. hatchetti, T4 | Parachlamydia acanthamoebae; Candidatus Paracaedibacter acanthamoebae (proposed name) |

| Austria, 2016 [77] | Seventy-eight water samples (66 cooling tower water: 2 cooling towers of hospital, 1 cooling tower of company, and 12 tap water) | Culture, FISH, real-time PCR, genotyping, and sequencing | 3 of 53 | Acanthamoeba spp. T4 | Paracaedibacter acanthamoebae; Rickettsiales; L. pneumophila |

| Canada, 2017 [78] | Five clinical isolates (human cornea, nasal swab, monkey kidney tissue Culture) and four environmental isolates (lake sediment, soil, and water reservoir); all ATCC strains | Axenic culture, amplifying and sequencing of bacterial 16S DNA | 3 of 9 | A. polyphaga ATCC 30173 and 50495; Acanthamoeba spp. PRA-220 | Holosporaceae (Rickettsiales); Mycobacterium spp.; Parachlamydia spp.; Ca. procabacter sp. (proposed name) |

| Malaysia, 2017 [79] | Isolates from air-conditioning outlets in wards and operating theatres (dust particles) | Axenic culture, PCR, genotyping, sequencing | 29 of 36 | Acanthamoeba spp. | Mycobacterium spp. (M. fortuitum, M. massiliense, M. abscessus, M. vanbaalenii, M. senegalense, M. trivial and M. vaccae); Legionella spp. (L. longbeachae, L. wadwaorthii, L. monrovica, L. massiliensis and L. feeleii); Pseudomonas spp. (P. stutzeri; P. aeruginosa; P. denitrificans; P. chlororaphis and P. knackmussi) |

| Malaysia, 2018 [80] | Air-condition (11 isolates), and keratitis isolates (2) | Axenic culture, PCR, sequencing, FISH (double), TEM | 6 of 13 | Acanthamoeba spp. T3; T4 and T5 | Ca. Caedibacter acanthamoebae/Ca. Paracaedimonas acanthamoeba and Ca. Jidaibacter acanthamoeba (proposed name) |

| Iran, 2019 [81] | Corneal scrapes and contact lenses isolate of keratitis patients | Culture, light microscopy, gram staining, PCR, sequencing | 7 of 15 | Acanthamoeba spp. T4 | E. coli; Achromobacter sps; P. aeruginosa; Aspergillus sp.; Mastadenovirus sp.; Microbacterium sp.; Stenotrophomonas maltophilia; Brevundimonas vesicularis and Brevibacillus sp. |

| Culture Type | Source of Acanthamoeba | Identified Intracellular Organism in Acanthamoeba | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axenic culture on PYG, KCM agar, NNA (n= 12) | Clinical isolates | Mycobacterium avium complex | [66] |

| Escherichia coli | [73] | ||

| Parachlamydia acanthamoebae and Ca. Paracaedibacter acanthamoebae | [22] | ||

| Environmental isolates | Candidatus spp. | [51] | |

| Protochlamydia | [69] | ||

| Burkholderia pickettii (biovar 2) | [43] | ||

| Cytophaga spp. | [46] | ||

| Mycobacterium spp. | [55] | ||

| P. aeruginosa and Agrobacterium tumefaciens | [74] | ||

| Mycobacterium spp. and Pseudomonas spp. | [79] | ||

| Clinical and environmental (both) isolates | Rickettsiales; Mycobacterium spp.; Parachlamydia spp. and Ca. procabacter sp. | [78] | |

| Candidatus spp. | [80] | ||

| Axenic culture in presence of antibiotics (n = 3) | Environmental isolates | Human adenoviruses | [58] |

| Paenibacillus spp.; Ca. Protochlamydia amoebophila; γ-Proteobacterium | [71] | ||

| Pseudomonas spp. | [72] | ||

| NNA with live/inactivated/killed bacteria (n= 18) | Clinical isolates | E. coli; Achromobacter sps; P. aeruginosa; Aspergillus sps; Mastadenovirus; Microbacterium sps; Stenotrophomonas maltophilia; Brevibacillus sps and Brevundimonas vesicularis | [81] |

| Caedibacter caryophilus and Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides | [56] | ||

| Environmental isolates | Ca. Babela massiliensis, Alphaproteobacterium bacillus, Mimivirus (Lentille), Virophage (Sputnik 2) | [65] | |

| Mimivirus-like particles | [67] | ||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia complex | [68] | ||

| Legionella spp. | [75] | ||

| Ca. procabacter sp. and Parachlamydia acanthamoebae | [57] | ||

| Protochlamydia spp. and Neochlamydia spp. | [76] | ||

| Paracaedibacter acanthamoebae; Rickettsiales; L. pneumophila | [77] | ||

| Pandoravirus | [59] | ||

| Parachlamydia sp.; Protochlamydia amoebophila; Candidatus spp. | [33] | ||

| Candidatus spp. | [61] | ||

| α- and β-Proteobacteria and chlamydiales | [62] | ||

| Chlamydiae; Legionellae | [64] | ||

| Clinical and environmental (both) isolates | Gram-negative; rods and coccus; non-acid fast; non-motile | [20] | |

| Parachlamydiaceae and Ca. Protochlamydia amoebophila | [49] | ||

| Ca. Procabacter acanthamoebae’ gen. nov., sp. nov. (proposed) | [53] | ||

| Legionella; Pseudomonas; Mycobacterium; Chlamydia | [21] | ||

| Live/inactivated/killed bacteria on NNA/SCGYE/TSB/PYG with antibiotics (n= 7) | Clinical isolates | Chlamydia spp. and Ca. Parachlamydia acanthamoebae | [42] |

| Rickettsiales spp. | [48] | ||

| Environmental isolates | Archaea like organism | [45] | |

| Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria | [40] | ||

| Paraceadibacter; Neochlamydia; Protochlamydia; Procabacter; Rickettsiales; Amoebophilus | [70] | ||

| Clinical and environmental (both) isolates | Candidatus spp. | [47] | |

| Flavobacterium spp. and Ca. Amoebophilus asiaticus | [52] |

| S.N. | Microorganisms | Interaction with Acanthamoeba spp. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Fungi | ||

| Histoplasma capsulatum | Co-culture with A. castellanii (ATCC 30324), cell lysis | [106] | |

| C. neoformans | Intracellular multiplication in A. castellanii strain 30324 | [107] | |

| Sporothrix schenckii | Co-culture with A. castellanii (ATCC 30324), cell lysis | [106] | |

| Fusarium conidia | Co-culture with different strains of A. castellanii (ATCC 30010, 50492), germinate in amoebal cells | [108] | |

| 2. | Viruses | ||

| HAdV | Co-culture with different isolates of Acanthamoeba, intracellular survival | [58] | |

| Coxsackie virus | Intracyst and intracellular survival in a clinical isolate of A. castellanii | [109] | |

| Mimivirus | Intracellular multiplication in A. polyphaga isolated from the water sample of a cooling tower | [54] | |

| Sample Type | Analysed Sample | Amoebal Host | Identified Intracellular Pathogenic Microbes in Acanthamoeba spp. | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical specimens | Corneal specimens | Acanthamoeba spp. | Legionella, Pseudomonas; Mycobacterium; Chlamydia | [21] |

| A. castellanii (ATCC 50370) | Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) | [66] | ||

| A. polyphaga (ATCC 50495) | Mycobacterium spp. | [78] | ||

| Acanthamoeba spp. | Rickettsiales | [48,111] | ||

| Acanthamoeba spp. T4 | P. aeruginosa; Aspergillus spp.; Mastadenovirus spp. | [81] | ||

| A. castellanii T4 | Caedibacter caryophilus; Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides (CFB) | [56] | ||

| A. hatchetti T4 | Parachlamydia acanthamoebae | [22] | ||

| Acanthamoeba T4 | E. coli | [73,81] | ||

| Human nasal mucosa | Acanthamoeba spp. | Chlamydia sps; Candidatus Parachlamydia acanthamoebae | [42] | |

| A. polyphaga (ATCC 30173) | Rickettsiales | [78] | ||

| Contact lens and fluid | Acanthamoeba spp. (A. triangularis) | Pandoravirus inopinatum | [59,60] | |

| Environmental samples | Tap water | Acanthamoeba (T2, T3, T4, T6, and T7) | Human adenoviruses | [58] |

| Recreational water sources | Acanthamoeba (T4, T5) | P. aeruginosa; A. tumefaciens | [74] | |

| Water treatment plant, natural pools | Acanthamoeba (T3, T4, T11) | Legionella spp. | [64,75] | |

| Sewage sludge and cooling tower water | A. palestinensis; A. polyphaga | Mimivirus | [54,67] | |

| Contact lens storage case/liquid | A. lugdunensis | Mycobacterium spp. | [55] | |

| A. polyphaga | Deltaproteobacterium; Mimivirus Lentille; Virophage Sputnik 2; Alphaproteobacterium bacillus | [65] | ||

| Soil and lake sediment | A. castellanii and A. royreba T4; A. pustulosa and A. polyphaga T2 | Parachlamydia sp.; Protochlamydia amoebophila; Ca. Paracaedibacter acanthamoebae; Ca. Amoebophilus asiaticus, Ca. Procabacter acanthamoebae | [33] | |

| Biofilm of a flushing cistern in a lavatory | Acanthamoeba spp. | Stenotrophomonas spp. | [68] | |

| Hot Spring | Acanthamoeba spp. T5 | Protochlamydia | [69] | |

| Hospital environment | Acanthamoeba spp. T4 | Protochlamydia spp.; Neochlamydia spp. | [76] | |

| Tap water | Acanthamoeba spp. | Ca. Amoebophilus asiaticus; α-Proteobacteria; Methylophilus sps | [61] | |

| Recreational water sources | Acanthamoeba spp. T4 and T5 | P. aeruginosa and Agrobacterium tumefaciens | [74] | |

| Lake water | Acanthamoeba sps T4 | Parachlamydia acanthamoebae; Ca. procabacter sp. | [57] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rayamajhee, B.; Subedi, D.; Peguda, H.K.; Willcox, M.D.; Henriquez, F.L.; Carnt, N. A Systematic Review of Intracellular Microorganisms within Acanthamoeba to Understand Potential Impact for Infection. Pathogens 2021, 10, 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10020225

Rayamajhee B, Subedi D, Peguda HK, Willcox MD, Henriquez FL, Carnt N. A Systematic Review of Intracellular Microorganisms within Acanthamoeba to Understand Potential Impact for Infection. Pathogens. 2021; 10(2):225. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10020225

Chicago/Turabian StyleRayamajhee, Binod, Dinesh Subedi, Hari Kumar Peguda, Mark Duncan Willcox, Fiona L. Henriquez, and Nicole Carnt. 2021. "A Systematic Review of Intracellular Microorganisms within Acanthamoeba to Understand Potential Impact for Infection" Pathogens 10, no. 2: 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10020225

APA StyleRayamajhee, B., Subedi, D., Peguda, H. K., Willcox, M. D., Henriquez, F. L., & Carnt, N. (2021). A Systematic Review of Intracellular Microorganisms within Acanthamoeba to Understand Potential Impact for Infection. Pathogens, 10(2), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10020225