Hominid Alluvial Corridor (HAC) of the Guadalquivir and Guadaíra River Valleys (Southern Spain): Geoarchaeological Functionality of the Middle Paleolithic Assemblages during the Upper Pleistocene

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Alluvial Geoarchaeological Hominid Corridor

2. Methods

2.1. Geoarchaeological Field Work

2.2. Lithic Industries: Techno-Typological Analysis, Traceology Protocol, and Use-Wear

2.3. Functionality Criteria of the Archaeological Sites

2.4. Chronological Framework

3. Results

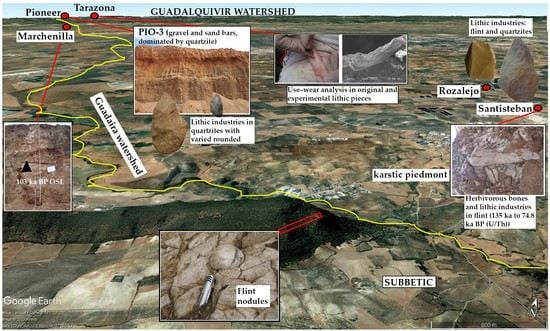

3.1. Guadaíra Watershed: Distribution of Archaeological Sites with Lithic Industries per Geomorphological Units

3.1.1. Karstic Piedmont of the Sierra de Esparteros and Cerro Santisteban

3.1.2. Guadaíra Alluvial Corridor: Three Geomorphological Transects

- Balbuan terraces: Upper Guadaíra cross-section

- (a)

- High terrace (+15 m): Eroded above, this is a conglomerate deposit with a 4 m maximum thickness, consisting of subangular to subrounded blocks, pebble, and fine-gravel, with a partially crusted carbonated matrix of medium to coarse sand and a planar structure. Lithologically, there is a predominance of sandstones and limestones, accompanied by ophites and flints. In the interior of the deposit, no lithic industries have been found, but on its geomorphological surface, some lithic elements of untumbled flint (cores and flakes) have been collected, although their scarcity and decontextualization make impossible any techno-typological characterization.

- (b)

- Lower terrace (+10 m): This terrace has also experienced erosion and exhibits a visible maximum thickness of 3 m. It comprises a deposit of pebbles and fine gravel with an abundant sandy–loam matrix. At the base, the deposit becomes more conglomeratic and channeled, while the top exhibits a planar structure. The lithology observed in this terrace is consistent with that of the upper terrace. No lithic industries have been identified within this alluvial terrace.

- (c)

- Colluvial–alluvial deposit: This deposit, with a maximum thickness of 1 m, overlays the current floodplain. It possesses a detrital nature, characterized by an abundant sandy–loam matrix. The base of the deposit shows channeling, and scattered pebbles and fine gravel can be found throughout. The lithology of this deposit is similar to that observed in the previous terraces. Some fragments of knapped flint have been recovered from the interior of this deposit.

- 2.

- Rozalejo River terraces: middle Guadaíra cross-section

- (a)

- High alluvial deposits (+15 m): These deposits consist of subangular gravel composed of limestone, sandstone, and flint, embedded in a reddish-brown sandy matrix. On the surface deposit in the Pintado Bajo area, unrounded lithic remnants made of flint and quartzite (cores and flakes) have been found. However, these remnants do not possess any specific techno-cultural characterization. It is worth noting that the presence of quartzite stones, including knapped ones and pebbles, in the Guadaíra watershed, where quartzite geological outcrops are absent, suggests deliberate human intention. This indicates that the raw material and lithic tools were brought from the Guadalquivir watershed to the Guadaíra River.

- (b)

- Alluvial deposit (+4 m): This deposit comprises gravel with similar characteristics to the previous one, but no lithic tools have been discovered.

- (c)

- Colluvial–alluvial deposit: This deposit is situated on reddish-brown sand and forms a superficial cover of gravel, which connects to the higher topographies of the stream’s right bank. Within this layer of gravel, a collection of 226 lithic artifacts was obtained, including 60 cores, 98 flakes, and 68 utensils (Figure 4). A total of 81% of these artifacts were knapped from various flint materials, 16% from quartzites, and the remaining 3% from sandstone and other raw materials. Most of the artifacts exhibit no alluvial rounding (R0) and have retained their sharp edges, except for a few instances that show slight edge softening possibly caused by water action (R1). Among the different types of cores, simple cores were the most prominent, with 32 examples, followed by centripetal cores (7), Levallois pieces (5), and a total of 7 polyhedral and prismatic pieces (with an additional 9 finished pieces).

- (d)

- A deposit of large reddish-brown sand without gravel was found in discordance with the underlying marl substratum.

- 3.

- La Barranca, Marchenilla, Membrilla, and La Liebre terraces: low Guadaíra cross-section

3.2. The Upper Pleistocene of Guadalquivir’s Terraces

3.2.1. Gravel Bars of Alluvial Deposits (T11 and T12, Pioneer and Fuente del Rey Sites)

3.2.2. Sand Bars of Alluvial Deposits with Pebble and Fine Gravels in Matrix (T11 Pioneer and Tarazona III Sites)

3.2.3. Massive Loam–Clay or Sandy–Clay Alluvial Deposits (T7 to T12: Muharra, Saltillo, Caleras, Toril, Tarazona II, Tarazona IIII, Pioneer, Aeropuerto, and Fuente del Rey sites)

3.2.4. Surface Geomorphological Deposits (T6 to T10: Pilar, Molinillos, Majapán, Cortés, Caleras, Toril, Padrecito, and Castilleja sites)

3.3. Raw Material, Lithic Industry Assemblages, and Use–Wear SEM Analyses

3.3.1. Raw Material: Significant Geographical Distribution of Archaeological Sites

3.3.2. Lithic Industry Assemblages and Techno-Typological Analysis

3.3.3. Use–Wear on the Quartzite Pieces’ Edges: SEM Analysis

- 1.

- Use–Wear on TARIII-4-level pieces

- 2.

- Use–Wear on TARIII-5 level pieces

- 3.

- Use–Wear on M2 Experimental carved piece

- 4.

- Use–Wear general functional interpretation

4. Discussion: Technological Strategies and Functionality in Guadaíra–Guadalquivir’s HAC

- (1)

- The first block, of relatively short duration, occurred from the end of the Middle Pleistocene to the beginning of the Upper Pleistocene (MIS6/MIS5) (>129 ka BP and <104 ka BP). During this period, there was a prevalence of notches, scrapers, and knapped pebbles in quartzite, indicating a high persistence of the archaic substratum and limited relevance of newer tendencies (TARIII-4 and 5, PION-1, 2, and 3).

- (2)

- The second block, of much longer duration, took place during the Upper Pleistocene (MIS3) (<110 ka BP and possibly even 50 ka BP). This block is characterized by lithic assemblages that exhibit a wide diversity of flake tools, including the presence of the Levallois technique and signs of bifacial tools. The influence of new techno-typological methods has become more evident, although the archaic Acheulian substratum continued to persist (TARII, TARIII-1, 2, and 3, SAL-2, CAS-1, MH4, PIO-4, AER-2, REY-1 and 3, PIL-1, MOL-1, MAJ-1, COR-1, CAL-1, TOR-3, PAD-1, BAR-1, MEM-1, LIE-1, ROZ-1, and SAN-1). Among these archaeological sites, only Santisteban and Membrilla feature industries exclusively in flint. In sites like ROZ-1, TARII, AER-2, PIO-1, 2, 3, BAR-1, and SAL-2, their assemblages have a high percentage of flint (>20%), while the rest of the archaeological sites primarily contain quartzites.

5. Conclusions

- The dispersion and geographical density of the archaeological sites throughout the study area of this study prove hominids moved during the Middle–Upper Pleistocene. The archaeological sites’ locations in the alluvial series of terraces, as well as on their surfaces, illustrate as much of an occupation of the valleys’ bottoms as of the highest terraces of the watersheds. We have characterized this geographical unity as the Guadaíra–Guadalquivir hominid alluvial corridor (HAC). It behaved as a multifunctional corridor, with three leading types of defined activities and another undefined (indeterminate site): food gathering and the distribution of raw materials (habitual or recurrent site and temporary site) and lithic knapping (lithic workshop site). Moreover, this research proposes, since an HAC has been identified, to manage its natural and cultural heritage as a protected geoarchaeological landscape.

- Two episodes with different durations have been identified: The first one, of short duration, occurred during the Late Middle Pleistocene and Early Upper Pleistocene (MIS6/MIS5) (>129 ka BP and <104 ka BP), and is characterized by notches, scrapers, and knapped pebbles, indicating the persistence of an archaic substratum. The second episode, which lasted much longer, took place during the Upper Pleistocene (MIS3) (<110 ka BP and possibly as recently as 50 ka BP). This episode showcases a wide diversity of flake tools, the presence of the Levallois technique, and bifacial tools.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wohl, E.; Brierley, G.; Cadol, D.; Coulthard, T.J.; Covino, T.; Fryirs, K.A.; Grant, G.; Hilton, R.G.; Lane, S.N.; Magilligan, F.J.; et al. Connectivity as an emergent property of geomorphic systems. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2019, 44, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexartza-Artza, I.; Wainwright, J. Hydrological connectivity: Linking concepts with practical implications. Catena 2009, 79, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremier, A.K.; Seo, J.I.; Nakamura, F. Watershed controls on the export of large wood from stream corridors. Geomorphology 2010, 117, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, L.J.; Wainwright, J.; Ali, G.A.; Tetzlaff, D.; Smith, M.W.; Reaney, S.M.; Roy, A.G. Concepts of Hydrological Connectivity: Research Approaches, Pathways and Future Agendas. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2013, 119, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, C.; Gourichon, L.; Blasco, R.; Carbonell, E.; Chacón, G.; Galván, B.; Hernández-Gómez, C.M.; Rosell, J.; Saladié, P.; Soler, J.; et al. High-resolution Neanderthal settlements in mediterranean Iberian Peninsula: A matter of altitude? Quat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 247, 106523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchionna, M.; Di Febbraro, M.; Carotenuto, F.; Rook, L.; Mondanaro, A.; Castiglione, S.; Serio, C.; Vero, A.V.; Tesone, G.; Piccolo, M.; et al. Fragmentation of Neanderthals’ pre-extinction distribution by climate change. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018, 496, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, J.A.; Aguirre, E.; Giles, F.; Gracia, J.; Santiago, A.; Mata, E.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Díaz del Olmo, F.; Baena, R.; Borja, F. Evolución del Pleistoceno en la Cuenca Baja del Miño, Sector La Guardia-Tuy. Secuencia de los Primeros Poblamientos Humanos y Registro Arqueológico. In Cuaternario Ibérico; Rodríguez Vidal, J., Ed.; AEQUA: Sevilla, Spain, 1997; pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, C.L.; Wilson, L. Resource selection of lithic raw materials in the Middle Paleolithic. J. Hum. Evol. 2011, 61, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruxelles, L.; Jarry, M. Climatic conditions, settlement patterns and cultures in the Paleolithic: The example of the Garonne Valley (southwest France). J. Hum. Evol. 2011, 61, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncel, M.H.; Moigne, A.M.; Combier, J. Towards the Middle Palaeolithic in Western Europe: The case of Orgnac 3 (southeastern France). J. Hum. Evol. 2012, 63, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turq, A.; Roebroeks, W.; Bourguignon, L.; Faivre, J.P. The fragmented character of Middle Palaeolithic stone tool technology. J. Hum. Evol. 2013, 65, 641–655. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047248413001899 (accessed on 30 January 2021). [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons, K.E.; Iovita, R.; Sprafke, T.; Glantz, M.; Talamo, S.; Horton, K.; Beeton, T.; Alipova, S.; Bekseitov, G.; Ospanov, Y.; et al. A chronological framework connecting the early Upper Palaeolithic across the Central Asian piedmont. J. Hum. Evol. 2017, 113, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Quintas, E.; Santonja, M.; Pérez-González, A.; Arnold, J.; Demuro, M.; Duval, M. A multidisciplinary overview of the Lower Mino River Terrace 1 system (NW Iberian Peninsula). Quat. Int. 2020, 566–567, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz del Olmo, F.; Vallespí, E.; Baena, R.; Recio, J.M. Terrazas Pleistocenas del Guadalquivir Occidental: Geomorfología, Suelos, Paleosuelos y Secuencia Cultural. In El Cuaternario en Andalucía Occidental; AEQUA: Sevilla, Spain, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Baena, R.; Díaz del Olmo, F. Cuaternario aluvial de la depresión del Guadalquivir: Episodios geomorfológicos y cronología paleomagnética. Geogaceta 1994, 15, 102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Vallespí, E. Las industrias achelenses en Andalucía: Ordenación y comentarios. Spal 1992, 1, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallespí, E. Comentario al Paleolítico Ibérico: Continuidad, etapas y perduraciones del proceso tecnocultural. Spal 1999, 9, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgland, D.R.; Antoine, P.; Limondin-Lozouet, N.; Santisteban, J.I.; Westaway, R.; White, M.J. The Palaeolithic occupation of Europe as revealed by evidence from the rivers: Data from IGCP 449. J. Quat. Sci. 2006, 21, 437–455. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jqs.1042 (accessed on 5 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Vallespí, E.; Fernández, J.J.; Caro, J.A. Las claves secuenciales del Paleolítico Inferior de Andalucía. Caesaraugusta 2007, 78, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, J.A. Evolución de Las Industrias Achelenses en Las Terrazas Fluviales del Bajo Guadalquivir (780.000–40.000 B.P.): Episodios Geomorfológicos y Secuencia Paleolítica. Spal 2000, 9, 189–207. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=625246 (accessed on 5 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Caro, J.A. Yacimientos e Industrias Achelenses en Las Terrazas Fluviales de la Depresión del Bajo Guadalquivir (Andalucía, España). Secuencia Estratigráfica, Caracterización Tecnocultural y Cronología. Carel Carmona Rev. Estud. Locales 2006, 4, 1423–1605. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/16632019/Yacimientos_e_industrias_achelenses_en_las_terrazas_fluviales_de_la_depresi%C3%B3n_del_bajo_Guadalquivir_Andaluc%C3%ADa_Espa%C3%B1a_._Secuencia_estratigr%C3%A1fica_caracterizaci%C3%B3n_tecnocultural_y_cronolog%C3%Ada (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Caro, J.A.; Díaz del Olmo, F.; Cámara, R.; Recio, J.M.; Borja, C. Geoarchaeological alluvial terrace system in Tarazona: Chronostratigraphical transition of Mode 2 to Mode 3 during the middle-upper pleistocene in the Guadalquivir Rivervalley (Seville, Spain). Quat. Int. 2011, 243, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, J.A.; Díaz del Olmo, F.; Barba, L.; Garrido, J.M.; Borja, C.; Recio, J.M. Paleolítico Medio Antiguo del valle del Guadalquivir: Las industrias de pequeñas lascas del yacimiento de Tarazona III (Sevilla, España). Spal 2021, 30.1, 9–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, R.; Fernández, J.J.; Guerrero, I.C.; Posada, J.C. La Terraza Compleja del río Guadalquivir en “Las Jarillas” (La Rinconada, Sevilla. SW de España): Cronoestratigrafía, industria lítica y macro-fauna asociada. Cuatern. Geomorfol. 2014, 28, 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz del Olmo, F.; Vallespí, E.; Baena, R. Bajo Guadalquivir y Afluentes Secundarios: Terrazas Fluviales y Secuencia Paleolítica. In Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía. Actividades Sistemáticas 1990; Junta de Andalucía: Sevilla, Spain, 1993; pp. 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Soil Survey England and Wales. Soil Survey Laboratory Methods; Technical monographs; Rothamsted Experimental Station: Harpenden, UK, 1974; 83p. [Google Scholar]

- Duchaufour, P. Manual de Edafología; Masson, T., Ed.; Publisher: Barcelona, Spain, 1975; 476p. [Google Scholar]

- Munsell Color. Munsell Soil Color Chart; Koll Morgen Instruments Corporation: Trapelo Road Waltham, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bordes, F. Typologie du Paléolithique Ancien et Moyen; DELMAS, Ed.; Publisher: Bordeaux, France, 1961; Volume 2, p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Tixier, J. Les Hacheraux dans L’Acheléen Nord-Africain. Notes Typologiques; Etrait du congrés Préhistorique du France. Compteredue de la XVª sossión Poitiers-Angouleme 15-22 juaillet; Société Préhistorique Française: Paris, France, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G. World Prehistory in New Perspective; Cambridge UniversityPress: Cambridge, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Boëda, E.; Geneste, J.M.; Meignen, L. Identification de chaînes opératoires lithiques du Paléolithique ancien et moyen. Paléo 1990, 2, 43–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boëda, E.; Kervazo, B.; Mercier, N.; Valladas, H. Barbas C’3 base (Dordogne). Une industrie bifaciale contemporaine des industries du Moustérien ancien: Une variabilité attendue. Quat. Nova 1996, VI, 465–504. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, J.A. Los Triedros del Yacimiento Achelense de El Caudal (Carmona, Sevilla): Ensayo de una Clasificación Tecnomorfológica. In Cuaternario Ibérico; Rodríguez Vidal, J., Ed.; AEQUA: Huelva, Spain, 1997; pp. 322–325. [Google Scholar]

- Santonja, M.; Pérez-González, A. (Eds.) Las Industrias Paleolíticas de La Maya I en su Ámbito Regional; Excavaciones Arqueológicas en España; Ministerio de Cultura: Madrid, Spain, 1984; Volume 135. [Google Scholar]

- Boëda, E. Le débitage discoïde et le débitage Levallois récurrent centripète. Bull. Société Préhistorique Française 1993, 90, 340–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boëda, E. Determination des Unités Techno-Fonctionnelles de Pièces Bifaciales Provenant de la Couche Acheuléenne C’3 Base du Site de Barbas I. In Les Industries à Outils Bifaciaux du Paléolithique Moyen d’Europe Occidentale; Cliquet, D., Ed.; ERAUL 98: Liège, Belgium, 2001; pp. 51–75. [Google Scholar]

- Inizan, M.L.; Reduron, M.; Roche, H.; Tixier, J. Technologie de la Pierre Taillée. Préhistoire de la Pierre Taillée 4; Cercle de Recherches et d’Etudes Préhistoriques (CREPS)/Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (C.N.R.S.): París, France; Meudon, France, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell, E.; Mosquera, M.; Ollé, A.; Rodríguez, X.P.; Sahnouni, M.; Sala, R.; Vergès, J.M. Structure morphotechnique de l’industrie lithique du Pléistocène inférieur et moyen d’Atupuerca (Burgos, Espagne). L’anthropologie 2001, 105, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turq, A. Réflexions sur le Biface Dans Quelques Sites du Paléolithique Ancien-Moyen en Grotte ou Abri du Nord-Est du Bassin Aquitain. In Les Industries à Outils Bifaciaux du Paléolithique Moyen d’Europe Occidentale; Cliquet, D., Ed.; ERAUL 98: Liège, Belgium, 2001; pp. 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, L.; Faivre, J.P.; Turq, A. Ramification des chaînes opératoires: Une spécificité du Moustérien? Paleo 2004, 16, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Geribàs, N.; Mosquera, M.; Vergès, J.M. What novice knappershave to learn to become expert stone toolmakers. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 2857–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soressi, M.; Geneste, J.M. The History and Efficacy of the Chaîne Opératoire Approach to Lithic Analysis: Studying Techniques to Reveal Past Societies in an Evolutionary Perspective. Paleoanthropology 2011, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegrin, J. Las Experimentaciones Aplicadas a la Tecnología Lítica. In La Investigación Experimental Aplicada a la Arqueología; Morgado, A., Baena, J., García, D., Eds.; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2013; pp. 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gibaja, J.F.; Clemente, I.; Mir, A. Análisis Funcional en Instrumentos de Cuarcita: El Yacimiento del Paleolítico Superior de la Cueva de la Fuente del Trucho (Colungo, Huesca). In Análisis Funcional. Su Aplicación al Estudio de Sociedades Prehistóricas; Clemente, I., Risch, R., Gibaja, J.F., Eds.; British Archaeological Reports, International Series; Hadrian Books Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2002; Volume 1073, pp. 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Reynard, J.; Henshilwood, C.S. Subsistence strategies during the later Middle Stone Age in thesouthern Cape of South Africa: Comparing the Still Bay of Blombos Cave with the Howiesons Poort of Klipdrift Shelter. J. Hum. Evol. 2017, 108, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditti, F.; Nunziante-Cesaro, S.; Parush, Y.; Gopher, A.; Barkai, R. Recycling for a purpose in the late Lower Paleolithic Levant: Use-wear and residue analyses of small sharp flint items indicate a planned and integrated subsistence behavior at Qesem Cave (Israel). J. Hum. Evol. 2019, 131, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.M.; Ruebens, K.; Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S.; Steele, T.E. Subsistence strategies throughout the African Middle Pleistocene: Faunal evidence for behavioral change and continuity across the Earlier to Middle Stone Age transition. J. Hum. Evol. 2019, 127, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmernman, D.W. Thermoluminescence Dating Using Fine Grain from Pottery. Archaeometry 1971, 13, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S.J. Thermoluminescen Dating Refinement of Quartz inclusion Method. Archaeometry 1970, 12, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambi, K.S.V.; Aitken, M.J. Annual dose conversion factors for TL and ESR dating. Archaeometry 1986, 28, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, M.J. TL Dating; Academy Press: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas, J.G.; Millán, A.; Sibilia, E.; Calderón, T. Factores que afectan a la determinación del error asociado a la datación absoluta por TL: Fabrica de ladrillos. Bol. Soc. Es. Min. 1990, 13, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Caro, J.J. El musteriense clásico de la paleocavidad del cerro de Santisteban (Morón de la Frontera, Sevilla). Spal 2003, 12, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, J.; Polo, J.; Bárez, S.; Cuartero, F.; Roca, M.; Lázaro, A.; Nebot, A.; Pérez-González, A.; Pérez, T.; Rus, I.; et al. Tecnología musteriense en la región madrileña: Un discurso enfrentado entre valles y páramos de la Meseta sur. Treb. D’arqueologia 2008, 14, 249–278. [Google Scholar]

- Eixea, A.; Villaverde, V.; Zilhão, J. Aproximación al aprovisionamiento de materias primas líticas en el yacimiento del Paleolítico medio del Abrigo de la Quebrada (Chelva, Valencia). Trab. Prehist. 2011, 68, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, F.; Moncel, M.H.; Nenzioni, G.; Onorevoli, G.; Peretto, C.; Combier, J. Widespread diffusion of technical innovations around 300,000 years ago in Europe as a reflection of anthropological and social transformations? New comparative data from the western Mediterranean sites of Orgnac (France) and Cave dall’Olio (Italy). J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2013, 32, 478–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goval, E.; Herisson, D.; Locht, J.L.; Coudenneau, A. Levallois points and triangular flakes during the Middle Palaeolithic in northwestern Europe: Considerations on the status of these pieces in the Neanderthal hunting toolkit in northern France. Quat. Int. 2016, 411, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meignen, L.; Bar-Yosef, O. Acheulo-Yabrudian and Early Middle Paleolithic at Hayonim Cave (Western Galilee, Israel): Continuity or break? J. Hum. Evol. 2020, 139, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.P.; Trinkaus, E. Isotopic evidence for the diets of European Neandertals and early modern humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 16034–16039. Available online: http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0305-4403(15)00113-2/sref48 (accessed on 28 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Rots, V. Insights into early Middle Palaeolithic tool use and hafting in Western Europe. The functional analysis of level IIa of the early Middle Palaeolithic site of Biache-Saint-Vaast (France). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruebens, K. Regional behaviour among late Neanderthal groups in Western Europe: A comparative assessment of late Middle Palaeolithic bifacial tool variability. J. Hum. Evol. 2013, 65, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amick, D.S. The recycling of material culture today and during the Paleolithic. Quat. Int. 2015, 361, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, C.; Alonso, R.; Bengoechea, A.; Colina, A.; Jordé, F.J.; Navazo, M.; Ortiz, J.E.; Pérez, S.; Torres, T. El Paleolítico Medio en el valle del Arlanza (Burgos). Los sitios de la Ermita, Millán y la Mina. Cuatern. Geomorfol. 2008, 22, 135–157. Available online: http://tierra.rediris.es/CuaternarioyGeomorfologia/images/vol22_3_4/08_Diez%20Alonso.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Baena, J.; Ortiz, I.; Torres, C.; Bárez, S. Recycling in abundance: Re-use and recycling processes in the Lower and Middle Paleolithic contexts of the central Iberian peninsula. Quat. Int. 2015, 361, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordá, J.F.; Baena, F.; Cabral, P.; García-Guinea, J.; Correcher, V.; Yravedra, J. Procesos sedimentarios y diagenéticos en el registro arqueológico del yacimiento pleistoceno de la cueva de El Esquilleu (Picos de Europa, norte de España). Cuatern. Gomorfología 2008, 22, 31–46. Available online: http://tierra.rediris.es/CuaternarioyGeomorfologia/images/vol22_3_4/02_Jorda%20Baena.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Cuartero, F.; Alcaraz-Castaño, M.; López-Recio, M.; Carrión-Santafé, E.; Baena-Preysler, J. Recycling economy in the Mousterian of the Iberian Peninsula: The case of study of El Esquilleu. Quat. Int. 2015, 361, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemorini, C.; Stiner, M.C.; Gopher, A.; Shimelmitz, R.; Barkai, R. Use-wear analysis of an Amudian laminar assemblage from the Acheuleo-Yabrudian of Qesem Cave, Israel. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2006, 33, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viallet, C. Macrotraces of Middle Pleistocene bifaces from two Mediterranean sites: Structural and functional analysis. Quat. Int. 2016, 411, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agam, A.; Zupancich, A. Interpreting the Quina and demi-Quina scrapers from Acheulo-YabrudianQesem Cave, Israel: Results of raw materials and functional analyses. J. Hum. Evol. 2020, 144, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Muñoz, J.; Bernal-Casasola, D.; Barrena-Tocino, A.; Domínguez-Bella, S.; Clemente-Conte, I.; Vijande-Vile, E.; Cantillo-Duarte, J.J.; Almisas-Cruz, S. Middle Palaeolithic Mode 3 lithic technology in the rock-shelter of Benzú (North Africa) and its immediate environmental relationships. Quat. Int. 2016, 413, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, P.; Coutard, S.; Guerin, G.; Deschodt, L.; Goval, E.; Locht, J.-L. Upper Pleistocene loess-palaeosols records from Northern France in the European context: Environmental background and dating of the Middle Palaeolithic. Quat. Int. 2016, 411, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hérisson, D.; Brenet, M.; Cliquet, D.; Moncel, M.H.; Richter, J.; Scott, B.; Van Baelen, A.; Di Modica, K.; De Loecker, D.; Ashton, N.; et al. The emergence of the Middle Palaeolithic in northwestern Europe and its southern fringes. Quat. Int. 2016, 411, 233–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Archaeological Site | Terrace Level | Deposit | Pieces nº | Raw Material (%) | Rounded | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qt | F | Qz | O | R0 | R1 | R2 | R3 | |||||

| GUADALQUIVIR RIVER | TAR-II | T11 | Loam-clay | 2885 | 72 | 25 | 2 | 1 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| TARIII-1 | T11 | Gravel bars | 264 | 92 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 99 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| TARIII-2 | T11 | Loam-clay | 118 | 94 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| TARIII-3 | T11 | Gravel and sand bars | 727 | 95 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| TARIII-4 | T11 | Gravel bars | 1275 | 85 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 60 | 30 | 9 | 1 | |

| TARIII-5 | T11 | Floating gravels | 25 | 84 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| MUH-4 | T7 | Loam-clay | 273 | 92 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 96 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| SAL-2 | T10 | Loam-clay | 312 | 78 | 20 | 0 | 2 | 81 | 17 | 2 | 0 | |

| CAS-1 | T10 | Geomorph. surface | 330 | 89 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 85 | 14 | 1 | 0 | |

| PIO-1 | T12 | Gravel bars | 62 | 70 | 25 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 27 | 51 | 11 | |

| PIO-2 | T12 | Gravel and sand bars | 222 | 74 | 22 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 37 | 38 | 18 | |

| PIO-3 | T12 | Gravel and sand bars | 108 | 48 | 50 | 0 | 2 | 17 | 43 | 31 | 9 | |

| PIO-4 | T12 | Loam-clay | 54 | 92 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 4 | 6 | 0 | |

| AER-2 | T12 | Loam-clay | 45 | 78 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 84 | 0 | 0 | |

| REY-1 | T12 | Gravel bars | 27 | 99 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 27 | 64 | |

| REY-3 | T12 | Loam-clay | 128 | 90 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 58 | 40 | 2 | 0 | |

| PIL-1 | T9 | Geomorph. surface | 590 | 91 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 91 | 8 | 1 | 0 | |

| MOL-1 | T9 | Geomorph. surface | 2159 | 94 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 92 | 4 | 0 | |

| MAJ-1 | T6 | Geomorph. surface | 195 | 99 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 58 | 37 | 5 | |

| COR-1 | T6 | Geomorph. surface | 222 | 98 | 1,5 | 0 | 0,5 | 0 | 54 | 44 | 2 | |

| CAL-1 | T8 | Geomorph. surface | 91 | 90 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 79 | 1 | 0 | |

| TOR-3 | T7 | Geomorph. surface | 190 | 85 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 94 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| PAD-1 | T7 | Geomorph. surface | 950 | 93 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 51 | 28 | 7 | |

| GUADAIRA RIVER | BAR-1 | Geomorph. surface | 44 | 75 | 23 | 2 | 0 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |

| MEM-1 | T (+10) | Gravels and fine grav. | 3 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| LIE-1 | Geomorph. surface | 45 | 96 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ROZ-1 | Coll/alluv | Geomorph. surface | 208 | 18 | 80 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| KARSTIC PIEDMONT | SAN-1 | Karst detrial fill | 1656 | 2 | 92 | 0 | 6 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Site | Stratigraphical Levels and Processes | Particle Size Distribution Blue: Sands Red: Silt-Clay | Munsell Colour | C0=3 % | Lithology | Chronology U/Th | Industry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerro Santisteban: karstic piedmond | 5.- Pedogenesis |  | 10YR 5/3 7.5YR 4/4 7.5YR 4/6 | - | |||

| 4.- Palustrine carbonates. |  | 7.5YR 7/6 | 76 | 69.8 ± 2.7 ka 71.7 ± 3.7 ka | |||

| Karstification espisode | |||||||

| 3.- Breccia (clast and stone block) | |||||||

| 2.2.- Detrital fill (brecciated conglomerate, clast; herbivorous teeth and bones) |  | 10YR 4/3 10YR 4/4 | 50 0 | Limestone Flint | 74.8 ± 13.2 ka 78.2 ± 5.5 ka 87.3 ± 3.9 ka 88.9 ± 5.9 ka 99.9 ± 21.2 ka 100.9 ± 15.3 ka 114.2 ± 10.5 ka 123.6 ± 7.1 ka 135.5 ± 9.9 ka 136.4 ± 18.1 ka | Middle Palaeolithic | |

| 2.1.- Detrital fill (silt, sand and limestone and flint clasts). |  | 10YR 6/2 7.5YR 8/4 | 56 90 | Limestone Flint | |||

| 1.- Substrate outcrop |

| Sample | 238U | 234U | 234U/238U | 230Th | 230Th/234U | 230Th/232Th | T (ky) | 234U/238U |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G2.1-1 | 15.36 ± 0.32 | 17.23 ± 0.34 | 1.122 ± 0.025 | 9.64 ± 0.21 | 0.559 ± 0.017 | 80 ± 12 | 87.3 ± 3.9 | 1.155 ± 0.033 |

| G2.1-2 | 13.03 ± 0.35 | 14.55 ± 0.38 | 1.117 ± 0.036 | 8.23 ± 0.29 | 0.566 ± 0.025 | 56.7 ± 11.3 | 88.9 ± 5.9 | 1.149 ± 0.046 |

| G2.2-1 | 14.49 ± 0.31 | 17.25 ± 0.34 | 1.191 ± 0.028 | 12.02 ± 0.30 | 0.697 ± 0.022 | 89 ± 17 | 123.6 ± 7.1 | 1.270 ± 0.040 |

| G2.2-2 | 13.22 ± 0.29 | 15.75 ± 0.33 | 1.192 ± 0.028 | 11.53 ± 0.37 | 0.733 ± 0.028 | 26.1 ± 3.6 | 135.5 ± 9.9 | 1.280 ± 0.041 |

| G2.3-1 | 2.567 ± 0.071 | 3.147 ± 0.081 | 1.226 ± 0.042 | 1.939 ± 0.252 | 0.616 ± 0.082 | 20.7 ± 9.6 | 99.9 ± 21.2 | 1.299 ± 0.056 |

| G2.3-2 | 2.560 ± 0.072 | 3.108 ± 0.081 | 1.214 ± 0.041 | 2.290 ± 0.147 | 0.737 ± 0.051 | 12.7 ± 2.5 | 136.4 ± 18.1 | 1.313 ± 0.060 |

| G2.4-1 | 2.005 ± 0.047 | 2.478 ± 0.053 | 1.236 ± 0.034 | 1.658 ± 0.082 | 0.669 ± 0.036 | 13.1 ± 2.2 | 114.2 ± 10.5 | 1.324 ± 0.047 |

| G2.4-thooth | 1.147 ± 0.040 | 1.402 ± 0.044 | 1.223 ± 0.054 | 0.869 ± 0.078 | 0.620 ± 0.059 | 96.1 ± 56.1 | 100.9 ± 15.3 | 1.296 ± 0.072 |

| G2.5-1 | 3.478 ± 0.083 | 3.942 ± 0.089 | 1.133 ± 0.033 | 1.986 ± 0.241 | 0.504 ± 0.062 | 23.7 ± 10.9 | 74.8 ± 13.2 | 1.164 ± 0.040 |

| G2.5-2 | 2.875 ± 0.061 | 3.434 ± 0.069 | 1.194 ± 0.029 | 1.793 ± 0.081 | 0.522 ± 0.026 | 15.2 ± 2.5 | 78.2 ± 5.5 | 1.242 ± 0.036 |

| W1.CR2-1 | 2.387 ± 0.045 | 2.825 ± 0.052 | 1.184 ± 0.014 | 1.360 ± 0.029 | 0.481 ± 0.014 | 25.8 ± 1.7 | 69.8 ± 2.7 | 1.223 ± 0.017 |

| W1.CR2-2 | 2.464 ± 0.047 | 2.879 ± 0.054 | 1.168 ± 0.014 | 1.411 ± 0.044 | 0.490 ± 0.018 | 24.2 ± 2.2 | 71.7 ± 3.7 | 1.206 ± 0.017 |

| Field Samples | LDR * Samples | Level | Grain Size (µ) | Radionuclide Concentrations | Equivalent Dose (Gy) | Annual Doce (mGy/year) | Factor K | Age (BP) | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U (ppm) | Th (ppm) | K2O (%) | H2O (%) | H2O Sat (%) | |||||||||

| GUA-II | MAD-145SDA | Level 5 | 2–10 | 0.93 | 1.811 | 0.05 | 9.21 | - | 80.69 | 0.78 | 0.05 | 10,3448 ± 7984 | |

| TG1-C | MAD-5791rBIN | Level 1 | 2–10 | 0.82 | 2.63 | 0.03 | 8.42 | - | 56.19 | 1.15 | 0.11 | 48,860 ± 3168 | |

| TCR-1 | MAD-5756rBIN | Level 4 | 2–10 | 1.53 | 9.51 | 0.13 | 13.09 | 13.09 | 155.39 | 1.48 | 0.10 | 104,993 ± 8415 | Caro et al., 2011 [22] |

| TCR-2 | MAD-5757rBIN | Level 6 | 2–10 | 2.02 | 7.47 | 0.73 | 8.60 | 8.60 | 195.25 | 1.77 | 0.08 | 110,310 ± 10,290 | Caro et al., 2011 [22] |

| TCR-3 | MAD-5763rBIN | Level 8 | 2–10 | 2.71 | 6.19 | 1.22 | 8.12 | 8.12 | 283.50 | 2.33 | 0.09 | 121,673 ± 9837 | Caro et al., 2011 [22] |

| TCR-4 | MAD-5761rBIN | Level 8 | 2–10 | 2.36 | 6.64 | 0.48 | 8.41 | 8.41 | 207.38 | 1.60 | 0.07 | 129,612 ± 13,312 | Caro et al., 2011 [22] |

| TCR-5 | MAD-5762rBIN | Level 9 | 2–10 | 2.19 | 8.23 | 1.19 | 11.99 | 11.99 | 287.91 | 2.08 | 0.08 | 138,418 ± 11,673 | Caro et al., 2011 [22] |

| Archaeological Site | Terrace Level | Deposit | Pieces nº | Retouched Tools (%) | Tecnical Balance | Raw Material (%) | Rounded Industry (%) | Funtionality Site | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QUARTZITE | Flint | Other | R0 | R1 | R2 | ≥R3 | HS | TS | LW | IN | ||||||

| TARIII-4 | T11 | Gravel bars | 1275 | 31 | 0.34 | 85 | 2 | 13 | 60 | 30 | 9 | 1 | yes | |||

| TAR-II | T11 | Loam-clay | 2885 | 30 | 0.47 | 72 | 25 | 3 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 0 | yes | |||

| CAS-1 | T10 | Geomorph. surface | 330 | 30 | 0.96 | 89 | 10 | 1 | 85 | 14 | 1 | 0 | yes | |||

| SAL-2 | T10 | Loam-clay | 312 | 33 | 1 | 78 | 20 | 2 | 81 | 17 | 2 | 0 | yes | |||

| SAN-1 | Karst detrial fill | 1656 | 36 | 5.5 | 2 | 92 | 6 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | yes | ||||

| MAJ-1 | T6 | Geomorph. surface | 195 | 33 | 0.22 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 58 | 37 | 5 | yes? | yes? | |||

| TARIII-2 | T11 | Loam-clay | 118 | 31 | 0.67 | 94 | 2 | 4 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 0 | yes | |||

| TOR-3 | T7 | Geomorph. surface | 190 | 31 | 0.67 | 12 | 3 | 94 | 6 | 0 | 0 | yes | ||||

| PIO-4 | T12 | Loam-clay | 54 | 48 | 1 | 92 | 8 | 0 | 90 | 4 | 6 | 0 | yes? | |||

| REY-3 | T12 | Loam-clay | 128 | 24 | 1 | 90 | 9 | 1 | 58 | 40 | 2 | 0 | yes? | |||

| LIE-1 | Geomorph. surface | 45 | 29 | 0.2 | 96 | 2 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | yes? | ||||

| BAR-1 | Geomorph. surface | 44 | 38 | 0.47 | 75 | 23 | 2 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | yes? | ||||

| COR-1 | T6 | Geomorph. surface | 222 | 25 | 0.25 | 1,5 | 0.5 | 0 | 54 | 44 | 2 | yes? | ||||

| CAL-1 | T8 | Geomorph. surface | 91 | 31 | 0.42 | 9 | 1 | 20 | 79 | 1 | 0 | yes? | ||||

| AER-2 | T12 | Loam-clay | 45 | 22 | 1.13 | 78 | 22 | 0 | 16 | 84 | 0 | 0 | yes? | yes? | ||

| PAD-1 | T7 | Geomorph. surface | 950 | 22 | 0.5 | 6 | 1 | 14 | 51 | 28 | 7 | yes? | yes? | |||

| PIL-1 | T9 | Geomorph. surface | 590 | 19 | 0.75 | 7 | 2 | 91 | 8 | 1 | 0 | yes? | yes? | |||

| ROZ-1 | Geomorph. surface | 228 | 16 | 0,7 | 15 | 83 | 2 | 68 | 26 | 5 | 1 | yes? | yes? | |||

| MUH-4 | T7 | Loam-clay | 273 | 18 | 1 | 92 | 7 | 1 | 96 | 4 | 0 | 0 | yes? | yes | ||

| TARIII-3 | T11 | Gravel and sand bars | 727 | 17 | 0.5 | 95 | 3 | 2 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 0 | yes | |||

| MOL-1 | T9 | Geomorph. surface | 2159 | 14 | 0.38 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 92 | 4 | 0 | yes | ||||

| TARIII-1 | T11 | Gravel bars | 264 | 20 | 0.67 | 92 | 5 | 3 | 99 | 1 | 0 | 0 | yes? | |||

| TARIII-5 | T11 | Gravels bars | 25 | 16 | 0,2 | 84 | 4 | 12 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 0 | yes | |||

| PIO-1 | T12 | Gravels and sand bars | 62 | 21 | 0.33 | 70 | 25 | 5 | 11 | 27 | 51 | 11 | yes | |||

| PIO-2 | T12 | Gravels and sand bars | 222 | 17 | 0.35 | 74 | 22 | 4 | 7 | 37 | 38 | 18 | yes | |||

| PIO-3 | T12 | Gravels bars | 108 | 19 | 1.53 | 48 | 50 | 2 | 17 | 43 | 31 | 9 | yes | |||

| REY-1 | T12 | Gravels and sand bars | 27 | 4 | 0.2 | 99 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 27 | 64 | yes | |||

| MEM-1 | T (+12m) | Gravels and fine gravels | 3 | 0 | - | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | yes | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Díaz del Olmo, F.; Caro Gómez, J.A.; Borja Barrera, C.; Recio Espejo, J.M.; Cámara Artigas, R.; Martínez Aguirre, A. Hominid Alluvial Corridor (HAC) of the Guadalquivir and Guadaíra River Valleys (Southern Spain): Geoarchaeological Functionality of the Middle Paleolithic Assemblages during the Upper Pleistocene. Geosciences 2023, 13, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences13070206

Díaz del Olmo F, Caro Gómez JA, Borja Barrera C, Recio Espejo JM, Cámara Artigas R, Martínez Aguirre A. Hominid Alluvial Corridor (HAC) of the Guadalquivir and Guadaíra River Valleys (Southern Spain): Geoarchaeological Functionality of the Middle Paleolithic Assemblages during the Upper Pleistocene. Geosciences. 2023; 13(7):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences13070206

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíaz del Olmo, Fernando, José A. Caro Gómez, César Borja Barrera, José M. Recio Espejo, Rafael Cámara Artigas, and Aránzazu Martínez Aguirre. 2023. "Hominid Alluvial Corridor (HAC) of the Guadalquivir and Guadaíra River Valleys (Southern Spain): Geoarchaeological Functionality of the Middle Paleolithic Assemblages during the Upper Pleistocene" Geosciences 13, no. 7: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences13070206

APA StyleDíaz del Olmo, F., Caro Gómez, J. A., Borja Barrera, C., Recio Espejo, J. M., Cámara Artigas, R., & Martínez Aguirre, A. (2023). Hominid Alluvial Corridor (HAC) of the Guadalquivir and Guadaíra River Valleys (Southern Spain): Geoarchaeological Functionality of the Middle Paleolithic Assemblages during the Upper Pleistocene. Geosciences, 13(7), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences13070206