Promoting the Social Inclusion of Children with ASD: A Family-Centred Intervention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

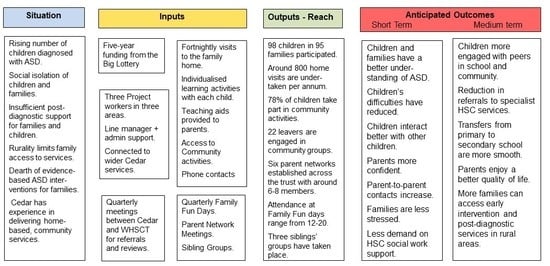

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Inputs and Activities

2.2. The Characteristics of Families and Children Involved with the Project

2.3. Evaluation of Project Outcomes

3. Results

3.1. Children’s Difficulties and Outcomes

3.2. Changes in the Children

3.3. Issues for Families and Outcomes

3.4. Outcomes for Families

3.5. Perceptions of Project Outcomes and Impact

3.5.1. The Most Successful Aspects of the Project

She had a great rapport with him, you know, she really met him at his level and he never said I don’t want her coming, never, never did. She has a fantastic rapport with him.(Mother JU)

They were very good at consulting with the parents in what we wanted and what we needed and then they would have done their plans around that.(Mother T)

They got a wee buddy system as well where he was going out with his friend, he met a wee friend a couple of days and the two of them went out together.(Mother T.)

The most successful aspect of the project is seeing families come together and be able to participate in family activities which all family members can be included in.(Project staff)

There’s brilliant relationships with us and Cedar... there’s a two-way flow of communication. When a family is known to Cedar... that family does not need to contact us. They do not seem to need us. Their issues have been dealt with it. That really allows our social workers to deal with families with even more complex needs. It’s been a real resource to us in that way: to staff as well as to the families.(Trust staff 4)

3.5.2. Improvements for the Project

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elsabbagh, M.; Divan, G.; Koh, Y.-J.; Kim, Y.S.; Kauchali, S.; Marcin, C.; Montiel-Nava, C.; Patel, V.; Paula, C.S.; Wang, C.; et al. Global Prevalence of Autism and Other Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Autism Res. 2012, 5, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vivanti, G.; Kasari, C.; Green, J.; Mandell, D.; Maye, M.; Hudry, K. Implementing and evaluating early intervention for children with autism: Where are the gaps and what should we do? Autism Res. 2017, 11, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane, L.; Chester, J.W.; Goddard, L.; Henry, L.; Hill, E. Experiences of autism diagnosis: A survey of over 1000 parents in the United Kingdom. Autism 2015, 20, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.; Weiss, J.A. Priority service needs and receipt across the lifespan for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2017, 10, 1436–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.; Falkmer, M.; Girdler, S. Community participation interventions for children and adolescents with a neurodevelopmental intellectual disability: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 37, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tint, A.; Weiss, J.A. Family wellbeing of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Autism 2015, 20, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantz, R.; Hansen, S.; Machalicek, W. Interventions to Promote Well-Being in Parents of Children with Autism: A Systematic Review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 5, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivers, C.; Jackson, J.B.; McGregor, C. Functioning Among Typically Developing Siblings of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 22, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Bremer, E.; Lloyd, M. Autism spectrum disorder: Family quality of life while waiting for intervention services. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 26, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, T.; Lord, C. A Pilot Study Promoting Participation of Families with Limited Resources in Early Autism Intervention. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2016, 2, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peacock, S.; Konrad, S.; Watson, E.; Nickel, D.; Muhajarine, N. Effectiveness of home visiting programs on child outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Public Health England. Introduction to Logic Models. 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evaluation-in-health-and-well-being-overview/introduction-to-logic-models (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robinson, L.; Bond, C.; Oldfield, J. A UK and Ireland survey of educational psychologists’ intervention practices for students with autism spectrum disorder. Educ. Psychol. Pr. 2017, 34, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, K.L.; Armitage, S.; Featherstone, J.; McQuillin, L.; Longley, S.; Pollard, N. Group-Based Parent Training Interventions for Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Literature Review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 6, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, E.A.; Fiani, T.; Stewart, J.L.; Neil, N.; McHugh, S.; Fienup, D.M. Randomized controlled trial of a sibling support group: Mental health outcomes for siblings of children with autism. Autism 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConkey, R. The rise in the numbers of school pupils with autism: A comparison of the four countries in the United Kingdom. Support Learn. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cidav, Z.; Munson, J.; Estes, A.M.; Dawson, G.; Rogers, S.; Mandell, D. Cost Offset Associated With Early Start Denver Model for Children With Autism. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Child Difficulties | Never Had a Problem | Was a Problem—Getting Better since Start of Project | Still a Problem at End of Project |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty in relating to other children and in making friends | 0 (0%) | 68 (81.0%) | 16 (19.0%) |

| Awareness of dangers, road safety | 8 (9.6%) | 58 (69.9%) | 17 (20.5%) |

| Difficulty with change | 10 (12.0%) | 56 (67.5%) | 17 (20.5%) |

| Joining in community activities | 12 (14.3%) | 59 (70.2%) | 13 (15.5%) |

| Anxious, agitated, nervous | 18 (22.8%) | 53 (64.6%) | 10 (12.7%) |

| Extreme fear and nervousness, lack of confidence, depressed | 33 (39.3%) | 45 (53.6%) | 6 (7.1%) |

| Anger, temper tantrums, meltdowns | 34 (40.5%) | 40 (47.65%) | 10 (11.9%) |

| Problem with following instructions | 36 (42.9%) | 38 (45.2%) | 10 (11.9%) |

| Personal care (toileting, dressing) | 50 (59.5%) | 23 (27.4%) | 11 (13.1%) |

| Difficulties in communication: speech and/or language | 51 (62.2%) | 21 (25.6%) | 10 (12.2%) |

| Issues with school, homework, etc. | 53 (63.1%) | 25 (29.8%) | 6 (7.1%) |

| Problem with bedtime, sleeping | 58 (69.0%) | 15 (17.9%) | 11 (13.1%) |

| Unusual interest in toys or objects | 66 (78.6%) | 10 (11.9%) | 8 (9.5%) |

| Problems with play, keeping self-occupied | 67 (79.8%) | 14 (16.7%) | 3 (3.6%) |

| Eating | 69 (82.1%) | 5 (6.0%) | 10 (11.9%) |

| Unusual response to something new | 69 (83.1%) | 13 (15.7%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Issues Families Can Face | Issues that were NOT a Concern | Project Helped and No Longer an Issue | Project Gave Some Help but Still an Issue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowing what services and supports are available to parents and children | 3 (3.5%) | 70 (82.4%) | 11 (12.9%) |

| Managing the child’s behaviour, temper tantrums, and meltdowns | 23 (27.7%) | 38 (45.8%) | 22 (26.5%) |

| Having time to spend with my other children | 25 (29.1%) | 50 (58.1%) | 11 (12.8%) |

| Taking the child out of the house, joining in community activities | 28 (32.6%) | 40 (46.5%) | 17 (19.8%) |

| Communicating with schools | 36 (41.9%) | 41 (47.7%) | 9 (10.5%) |

| Relationships with siblings (or other children) | 36 (42.9%) | 32 (38.1%) | 16 (19.0%) |

| Finding activities all the families can join in | 37 (43.0%) | 34 (39.5%) | 15 (17.4%) |

| Worries about the child’s future | 41 (47.7%) | 7 (8.1%) | 37 (43.0%) |

| Lack of confidence in how to manage my child | 46 (47.9%) | 20 (23.8%) | 18 (21.4%) |

| Meeting other parents and sharing experiences | 44 (51.2%) | 38 (44.2%) | 4 (4.7%) |

| Understanding what it means to have Autism/ASD | 51 (59.3%) | 29 (33.7%) | 6 (7.0%) |

| Family quality of life | 65 (79.3%) | 12 (14.6%) | 5 (6.1%) |

| Main caregiver often feels anxious or depressed | 70 (81.4%) | 3 (3.5%) | 13 (15.1%) |

| Main caregiver has people to turn to if s/he has a problem | 74 (86.0%) | 7 (8.1%) | 5 (5.8%) |

| Main Themes | Subthemes | Supporting Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Impact on the children | Social Interaction | N is an only child and his social skills were lacking. But whenever she would have taken him out and interacted him with other children as well, we could see a very big change in the social skills (Mother S). |

| Improved behaviour | He was very frustrated, would have lashed out a lot, he would have cried and screamed a lot. So over time, she built up taking him out for like for a half an hour at one of the wee local centres … where anybody could come in with their children. And he actually started interacting with the kids. (Mother TR) | |

| Acquisition of new skills | The project helped my child to understand a lot of topics including personal safety, peer pressure, and safe strangers (Mother TA) | |

| Impact on families | New learning for parents | The project was a massive help to my son and our whole family, to help us understand his condition and work together as a family to help him. (Mother DH) |

| Increased confidence | They give us the confidence to think that you’re not doing a bad job … you’re doing your best. They were able to make people feel more confident in themselves that ‘I can do this’. (Mother H). | |

| Free time | I have a little six-year-old too. It’s very difficult for her when you have a little autistic child so, it gave me a bit of time with her. And she also went out too with the Cedar person at times, which also gave me a bit of time to do things about the house or go and do a bit of shopping and stuff like that. (Father). | |

| Meeting other parents | There was a family day and then a thing at Halloween and … you’re meeting other parents there as well with children who are similar, you know, so that’s quite good so it is. (Mother JO). |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McConkey, R.; Cassin, M.-T.; McNaughton, R. Promoting the Social Inclusion of Children with ASD: A Family-Centred Intervention. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10050318

McConkey R, Cassin M-T, McNaughton R. Promoting the Social Inclusion of Children with ASD: A Family-Centred Intervention. Brain Sciences. 2020; 10(5):318. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10050318

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcConkey, Roy, Marie-Therese Cassin, and Rosie McNaughton. 2020. "Promoting the Social Inclusion of Children with ASD: A Family-Centred Intervention" Brain Sciences 10, no. 5: 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10050318

APA StyleMcConkey, R., Cassin, M. -T., & McNaughton, R. (2020). Promoting the Social Inclusion of Children with ASD: A Family-Centred Intervention. Brain Sciences, 10(5), 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10050318