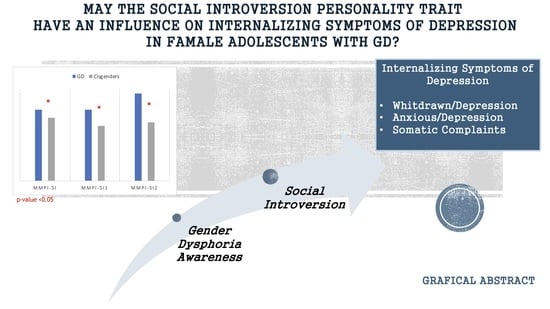

Social Introversion Personality Trait as Predictor of Internalizing Symptoms in Female Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Psychometric Assessment

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strenght and Limitations

4.2. Future Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roberts, B.W. Back to the Future: Personality and Assessment and Personality Development. J. Res. Pers. 2009, 43, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuovinen, S.; Tang, X.; Salmela-Aro, K. Introversion and Social Engagement: Scale Validation, Their Interaction, and Positive Association with Self-Esteem. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 590748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, J.A.; MacQueen, G. Neurobiological Factors Linking Personality Traits and Major Depression. Can. J. Psychiatry 2008, 53, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, I.; de Lima, M.P.; Matos, M.; Figueiredo, C. Personality and Subjective Well-Being: What Hides behind Global Analyses? Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 105, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jylhä, P.; Melartin, T.; Rytsälä, H.; Isometsä, E. Neuroticism, Introversion, and Major Depressive Disorder—Traits, States, or Scars? Depress. Anxiety 2009, 26, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jylhä, P.; Melartin, T.; Isometsä, E. Relationships of Neuroticism and Extraversion with Axis I and II Comorbidity among Patients with DSM-IV Major Depressive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 114, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton-Howes, G.; Horwood, J.; Mulder, R. Personality Characteristics in Childhood and Outcomes in Adulthood: Findings from a 30 Year Longitudinal Study. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.S.H.; Chua, J.; Tay, G.W.N. The Diagnostic and Predictive Potential of Personality Traits and Coping Styles in Major Depressive Disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erić, A.P.; Erić, I.; Ćurković, M.; Dodig-Ćurković, K.; Kralik, K.; Kovač, V.; Filaković, P. The Temperament and Character Traits in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Affective Disorder with and without Suicide Attempt. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017, 29, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowsky, D.S. Introversion and Extroversion: Implications for Depression and Suicidality. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2001, 3, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostacoli, L.; Zuffranieri, M.; Cavallo, M.; Zennaro, A.; Rainero, I.; Pinessi, L.; Pacchiana Parravicini, M.V.; Ladisa, E.; Furlan, P.M.; Picci, R.L. Age of Onset of Mood Disorders and Complexity of Personality Traits. ISRN Psychiatry 2013, 2013, 246358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, M.-H.; Chen, H.-C.; Lu, M.-L.; Feng, J.; Chen, I.-M.; Wu, C.-S.; Chang, S.-W.; Kuo, P.-H. Risk Profiles of Personality Traits for Suicidality among Mood Disorder Patients and Community Controls. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 137, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, B.; Liao, J.; Li, Y.; Jia, G.; Yang, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Luo, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Personality Characteristics, Defense Styles, Borderline Symptoms, and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in First-Episode Major Depressive Disorder. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 989711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Sulley, S.; Ndanga, M.; Mensah, N. Pediatric and Adolescent Mood Disorders: An Analysis of Factors That Influence Inpatient Presentation in the United States. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2022, 9, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, L.; Majmudar, I.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Tollit, M.A.; Pang, K.C. Assessment of Quality of Life of Transgender and Gender-Diverse Children and Adolescents in Melbourne, Australia, 2017–2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2254292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikummoon, P.; Oonarom, A.; Manojai, N.; Maneeton, B.; Maneeton, N.; Wiriyacosol, P.; Chiawkhun, P.; Kawilapat, S.; Homkham, N.; Traisathit, P. Experiences of Being Bullied and the Quality of Life of Transgender Women in Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. Transgend. Health 2023, 8, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puckett, J.A.; Dyar, C.; Maroney, M.R.; Mustanski, B.; Newcomb, M.E. Daily Experiences of Minority Stress and Mental Health in Transgender and Gender-Diverse Individuals. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 2023; advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.J.; Ybarra, M.L.; Goodman, K.L.; Strøm, I.F. Polyvictimization Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, F. Shifts in Assigned Sex Ratios at Gender Identity Clinics Likely Reflect Changes in Referral Patterns. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 948–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, K.J.; VanderLaan, D.P.; Aitken, M. The Contemporary Sex Ratio of Transgender Youth That Favors Assigned Females at Birth Is a Robust Phenomenon: A Response to the Letter to the Editor Re: “Shifts in Assigned Sex Ratios at Gender Identity Clinics Likely Reflect Change in Referral Patterns". J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 949–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, M.; Steensma, T.D.; Blanchard, R.; VanderLaan, D.P.; Wood, H.; Fuentes, A.; Spegg, C.; Wasserman, L.; Ames, M.; Fitzsimmons, C.L.; et al. Evidence for an Altered Sex Ratio in Clinic-Referred Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianchetti, C.; Fancello, G.S. SAFA: Scale Psichiatriche di Autosomministrazione per Fanciulli e Adolescenti: Manuale; O.S.: Florence, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cianchetti, C.; Bianchi, E.; Guerrini, R.; Baglietto, M.G.; Briguglio, M.; Cappelletti, S.; Casellato, S.; Crichiutti, G.; Lualdi, R.; Margari, L.; et al. Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression and Family’s Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018, 79, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacinovich, R.; Gadda, S.; Maserati, E.; Bomba, M.; Neri, F. Preadolescent Anxiety: An Epidemiological Study Concerning an Italian Sample of 3,479 Nine-Year-Old Pupils. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2012, 43, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sighinolfi, C.; Norcini Pala, A.; Chiri, L.; Marchetti, I.; Sica, C. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS): Traduzione e Adattamento Italiano. Psicoter. Cogn. Comport. 2010, 16, 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Giromini, L.; Velotti, P.; de Campora, G.; Bonalume, L.; Cesare Zavattini, G. Cultural Adaptation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale: Reliability and Validity of an Italian Version. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 68, 989–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritschel, L.A.; Tone, E.B.; Schoemann, A.M.; Lim, N.E. Psychometric Properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale across Demographic Groups. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Simón, I.; Penelo, E.; de la Osa, N. Factor Structure and Measurement Invariance of the Difficulties Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) in Spanish Adolescents. Psicothema 2014, 26, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orbach, I.; Mikulincer, M. The Body Investment Scale: Construction and Validation of a Body Experience Scale. Psychol. Assess. 1998, 10, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, J.H.; Perpiñá, C.; Roncero, M.; Botella, C. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire-Appearance Scales in Early Adolescents. Body Image 2017, 21, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.I.; Fernandes, J.; Machado, P.P.P.; Gonçalves, S. The Portuguese Version of the Body Investment Scale: Psychometric Properties and Relationships with Disordered Eating and Emotion Dysregulation. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbach, I.; Stein, D.; Shani-Sela, M.; Har-Even, D. Body Attitudes and Body Experiences in Suicidal Adoelscents. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2001, 31, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.; Gutierrez, P.M.; Schweers, R.; Fang, Q.; Holguin-Mills, R.L.; Cashin, M. Psychometric Evaluation of the Body Investment Scale for Use with Adolescents. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 66, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butcher, J.N. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-470-47921-6. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Craig, E. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and Profile; Thomas, M., Ed.; Child Behavior Checklist: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, P.; Kwong, S.; Tang, C.; Ho, T.; Hung, S.; Lee, C.; Hong, S.; Chiu, C.; Liu, W. Test-Retest Reliability and Criterion Validity of the Chinese Version of CBCL, TRF, and YSR. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2006, 47, 970–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBM. SPSS Statistics 28 Documentation. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/ibm-spss-statistics-28-documentation (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Frigerio, A.; Cattaneo, C.; Cataldo, M.; Schiatti, A.; Molteni, M.; Battaglia, M. Behavioral and Emotional Problems Among Italian Children and Adolescents Aged 4 to 18 Years as Reported by Parents and Teachers. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2004, 20, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). DSM-5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, M.N.; Boulton, K.A.; Kozlowska, K.; McClure, G.; Guastella, A.J. The Co-Occurrence of Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Gender Dysphoria: Characteristics within a Paediatric Treatment-Seeking Cohort and Factors That Predict Distress Pertaining to Gender. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 149, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.X.; Roslan, N.S.; Izhar, L.I.; Abdul Rahman, M.; Faye, I.; Ho, E.T.W. Conversational Task Increases Heart Rate Variability of Individuals Susceptible to Perceived Social Isolation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.; Butler, C.; Cooper, K. Gender Minority Stress in Trans and Gender Diverse Adolescents and Young People. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1182–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, M.-T.; Hinds, D.A.; Tung, J.Y.; Franz, C.; Fan, C.-C.; Wang, Y.; Smeland, O.B.; Schork, A.; Holland, D.; Kauppi, K.; et al. Genome-Wide Analyses for Personality Traits Identify Six Genomic Loci and Show Correlations with Psychiatric Disorders. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzy, J.; Brunelle, J.; Cohen, D.; Condat, A. Transidentities and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 323, 115176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallitsounaki, A.; Williams, D.M. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Gender Dysphoria/Incongruence. A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2022; Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrier, V.; Greenberg, D.M.; Weir, E.; Buckingham, C.; Smith, P.; Lai, M.-C.; Allison, C.; Baron-Cohen, S. Elevated Rates of Autism, Other Neurodevelopmental and Psychiatric Diagnoses, and Autistic Traits in Transgender and Gender-Diverse Individuals. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, O.; Wei, Y.; Warrier, V.; Richards, G. Autistic Traits, Empathizing-Systemizing, and Gender Diversity. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 2077–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakowski, A. Balanced Sex Ratios and the Autism Continuum. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 92, e35–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Cohen, S. The Extreme Male Brain Theory of Autism. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2002, 6, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Q.; Yu, B. Gender Differences in the Influence of Social Isolation and Loneliness on Depressive Symptoms in College Students: A Longitudinal Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qian, X.; Gong, J.; Dong, H.; Chai, X.; Chao, H.; Yang, X. Previous School Bullying-Associated Depression in Chinese College Students: The Mediation of Personality. Behav. Sci. 2022, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witvliet, M.; Brendgen, M.; van Lier, P.A.C.; Koot, H.M.; Vitaro, F. Early Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: Prediction from Clique Isolation, Loneliness, and Perceived Social Acceptance. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armiya’u, A.; Yıldırım, M.; Muhammad, A.; Tanhan, A.; Young, J. Mental Health Facilitators and Barriers during COVID-19 in Nigeria. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2022; Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyumgaç, I.; Tanhan, A.; Kiymaz, M.S. Understanding the Most Important Facilitators and Barriers for Online Education during COVID-19 through Online Photovoice Methodology. Int. J. High. Educ. 2021, 10, 166–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic and Clinical Features | GD (n = 33) | Cisgender (n = 36) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median (IQR)) | 16 (3) | 15 (3) | 0.11 b |

| Personal and family history of psychiatric disorders | |||

| Family History of psychiatric disorders n (%) | 16 (45.7%) | 22 (62.9%) | 0.23 a |

| Anxiety n (%) Depression n (%) Bipolar Disorder n (%) Psychosis n (%) | 9 (27.3%) 11 (33.3%) 2 (6.1%) 5 (15.2%) | 11 (31.4%) 11 (31.4%) 7 (20%) 3 (8.6%) | 0.71 a 0.87 a 0.09 a 0.40 a |

| Bullying suffered n (%) | 16 (48.5%) | 11 (30.6%) | 0.13 a |

| NSSI and Suicidal behavior | |||

| NSSI behavior n (%) Suicidal ideation n (%) Suicidal acting n (%) | 20 (60.6%) 19 (57.6%) 8 (24.2%) | 15 (41.7%) 19 (52.8%) 9 (25%) | 0.17 a 0.69 a 0.94 a |

| GD Sample | Cisgender | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-5 Diagnosis | n (%) | n (%) | p-Value | ||

| MDD | 10 (30.3%) | 12 (33.3%) | 0.78 a | ||

| PDD | 11 (33.3%) | 7 (19.4%) | 0.19 a | ||

| DMDD | 4 (12.1%) | 5 (13.9%) | 0.83 a | ||

| OSD | 8 (24.2%) | 12 (33.3%) | 0.40 a | ||

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | p-value | |

| D-TOT | 108.27 (1.54) | 15 (3) | 100.91 (29.15) | 109 (42) | 0.290 |

| BIS-C | 15.78 (3.61) | 16 (5) | 17.00 (5.02) | 17 (6) | 0.28 |

| BIS-T | 16.84 (5.44) | 18 (9) | 18.84 (5.68) | 19 (8) | 0.16 |

| BIS-P | 20.22 (5.20) | 21 (6) | 21.16 (6.12) | 22 (10) | 0.57 b |

| BIS-I | 13.59 (3.60) | 14 (5) | 21.23 (7.73) | 23 (11) | <0.01 * |

| MMPI-SI | 62.46 (13.54) | 62 (23) | 54.54 (9.61) | 55 (16) | 0.02 * |

| MMPI-SI 1 | 58.21 (12.91) | 62 (20) | 49.15 (10.66) | 48 (20) | 0.01 * |

| MMPI-SI 2 | 67.29 (14.01) | 76 (25) | 55.81 (11.79) | 51 (16) | 0.01 *b |

| MMPI-SI 3 | 45.54 (10.75) | 45 (20) | 45.46 (8.38) | 45 (11) | 0.98 |

| YSR-Anx/Depr | 68.73 (14.14) | 67 (20) | 65.59 (12.61) | 61 (13) | 0.34 b |

| YSR-Withdr/Depr | 68.93 (12.80) | 66 (26) | 64.04 (10.09) | 64 (14) | 0.17 b |

| YSR-Som Comp | 61.10 (9.47) | 63 (16) | 60.89 (9.85) | 57 (16) | 0.98 b |

| GD Sample | ||||||||

| YSR-Whitdrawn/Depression (Cut-Off > 65: n = 16) | ||||||||

| B | S.E. | Wald | gl | Sign. | Exp(B) | C.I. Inf. | C.I. Sup | |

| MMPI-SI | 0.19 | 0.07 | 6.77 | 1 | 0.01 | 1.21 | 1.05 | 1.40 |

| Constant | −12.34 | 4.73 | 6.82 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.00 | ||

| MMPI-SI1 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 5.43 | 1 | 0.02 | 1.12 | 1.02 | 1.24 |

| Constant | −7.18 | 3.09 | 5.41 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||

| MMPI-SI2 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 5.55 | 1 | 0.02 | 1.13 | 1.02 | 1.25 |

| Constant | −8.58 | 3.72 | 5.30 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.00 | ||

| YSR-Anxious/Depression (Cut-Off > 65: n = 18) | ||||||||

| B | S.E. | Wald | gl | Sign. | Exp(B) | C.I. Inf. | C.I. Sup | |

| MMPI-SI | 0.09 | 0.04 | 4.81 | 1 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.18 |

| Constant | −4.98 | 2.46 | 4.10 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.01 | ||

| MMPI-SI1 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.78 | 1 | 0.18 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.12 |

| Constant | −2.26 | 2.03 | 1.24 | 1 | 0.27 | 0.104 | ||

| MMPI-SI2 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 6.19 | 1 | 0.01 | 1.10 | 1.02 | 1.18 |

| Constant | −5.69 | 2.50 | 5.19 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||

| YSR-Somatic Complaints (Cut-Off > 65: n = 11) | ||||||||

| B | S.E. | Wald | gl | Sign. | Exp(B) | C.I. Inf. | C.I. Sup | |

| MMPI-SI | 0.28 | 0.12 | 5.62 | 1 | 0.02 | 1.32 | 1.05 | 1.67 |

| Constant | −18.47 | 7.72 | 5.72 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.00 | ||

| MMPI-SI1 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 5.73 | 1 | 0.02 | 1.16 | 1.03 | 1.31 |

| Constant | −9.51 | 3.96 | 5.77 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.00 | ||

| MMPI-SI2 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 4.97 | 1 | 0.03 | 1.13 | 1.02 | 1.27 |

| Constant | −9.08 | 4.11 | 4.88 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.00 | ||

| Cisgender Sample | ||||||||

| YSR-Whitdrawn/Depression (Cut-Off > 65: n = 12) | ||||||||

| B | S.E. | Wald | gl | Sign. | Exp(B) | C.I. Inf. | C.I. Sup | |

| MMPI-SI | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.21 | 1 | 0.27 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 1.18 |

| Constant | −3.62 | 3.08 | 1.38 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.03 | ||

| MMPI-SI1 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 1 | 0.75 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 1.10 |

| Constant | −0.95 | 2.16 | 0.20 | 1 | 0.66 | 0.39 | ||

| MMPI-SI2 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 1.93 | 1.08 |

| Constant | −0.41 | 2.23 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.85 | 0.66 | ||

| YSR-Anxious/Depression (Cut-Off > 65: n = 14) | ||||||||

| B | S.E. | Wald | gl | Sign. | Exp(B) | C.I. Inf. | C.I. Sup | |

| MMPI-SI | 0.07 | 0.06 | 1.31 | 1 | 0.25 | 1.07 | 0.95 | 1.20 |

| Constant | −4.47 | 3.39 | 1.74 | 1 | 0.19 | 0.01 | ||

| MMPI-SI1 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.41 | 1 | 0.52 | 1.03 | 0.94 | 1.12 |

| Constant | −2.13 | 2.32 | 0.85 | 1 | 0.36 | 0.12 | ||

| MMPI-SI2 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.44 | 1 | 0.23 | 1.05 | 0.97 | 1.15 |

| Constant | −3.57 | 2.47 | 2.09 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.03 | ||

| YSR-Somatic Complaints (Cut-Off > 65: n = 8) | ||||||||

| B | S.E. | Wald | gl | Sign. | Exp(B) | C.I. Inf. | C.I. Sup | |

| MMPI-SI | 0.11 | 0.07 | 2.83 | 1 | 0.09 | 1.11 | 0.98 | 1.27 |

| Constant | −6.57 | 3.71 | 3.15 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.00 | ||

| MMPI-SI1 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 2.23 | 1 | 0.14 | 1.07 | 0.98 | 1.18 |

| Constant | −4.14 | 2.53 | 2.68 | 1 | 0.10 | 0.02 | ||

| MMPI-SI2 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 2.35 | 1 | 0.13 | 1.07 | 0.98 | 1.17 |

| Constant | −4.39 | 2.60 | 2.85 | 1 | 0.10 | 0.01 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Furente, F.; Matera, E.; Margari, L.; Lavorato, E.; Annecchini, F.; Scarascia Mugnozza, F.; Colacicco, G.; Gabellone, A.; Petruzzelli, M.G. Social Introversion Personality Trait as Predictor of Internalizing Symptoms in Female Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093236

Furente F, Matera E, Margari L, Lavorato E, Annecchini F, Scarascia Mugnozza F, Colacicco G, Gabellone A, Petruzzelli MG. Social Introversion Personality Trait as Predictor of Internalizing Symptoms in Female Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(9):3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093236

Chicago/Turabian StyleFurente, Flora, Emilia Matera, Lucia Margari, Elisabetta Lavorato, Federica Annecchini, Francesca Scarascia Mugnozza, Giuseppe Colacicco, Alessandra Gabellone, and Maria Giuseppina Petruzzelli. 2023. "Social Introversion Personality Trait as Predictor of Internalizing Symptoms in Female Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 9: 3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093236

APA StyleFurente, F., Matera, E., Margari, L., Lavorato, E., Annecchini, F., Scarascia Mugnozza, F., Colacicco, G., Gabellone, A., & Petruzzelli, M. G. (2023). Social Introversion Personality Trait as Predictor of Internalizing Symptoms in Female Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(9), 3236. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093236