Pathogenic and Non-Pathogenic Fungal Communities in Wheat Grain as Influenced by Recycled Phosphorus Fertilizers: A Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Experiment

2.2. Soil and Meteorological Conditions

2.3. Isolation of Fungi from Grain

2.4. Isolation of Fungal DNA and PCR Amplification

2.5. Illumina MiSeq Sequencing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Fungal Colony Counts on Wheat Grain

3.2. Percentage of Pathogenic and Saprotrophic Fungi Colonizing Grain on PDA

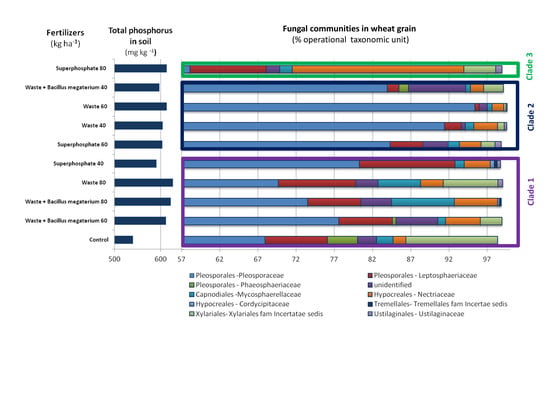

3.3. Structure and Composition of Fungal Communities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicolaisen, M.; Justesen, A.F.; Knorr, K.; Wang, J.; Pinnschmidt, H.O. Fungal communities in wheat grain show significant co-existence patterns among species. Fungal Ecol. 2014, 11, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larran, S.; Perelló, A.; Simón, M.R.; Moreno, V. The endophytic fungi from wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 23, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachowska, U.; Waśkiewicz, A.; Jedryczka, M. Using a protective treatment to reduce Fusarium pathogens and mycotoxins contaminating winter wheat grain. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 26, 2277–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Sui, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Ji, C.; Song, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, C.; Sa, R. Isolation and characterization of phosphofungi, and screening of their plant growth-promoting activities. AMB Express 2018, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassegawa, R.H.; Fonseca, H.; Fancelli, A.L.; da Silva, V.N.; Schammass, E.A.; Reis, T.A.; Corrêa, B. Influence of macro- and micronutrient fertilization on fungal contamination and fumonisin production in corn grains. Food Control 2008, 19, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachowska, U.; Stasiulewicz-Paluch, A.D.; Głowacka, K.; Mikołajczyk, W.; Kucharska, K. Response of epiphytes and endophytes isolated from winter wheat grain to biotechnological and fungicidal treatments. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2013, 22, 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Taghinasab, M.; Imani, J.; Steffens, D.; Glaeser, S.P.; Kogel, K.H. The root endophytes Trametes versicolor and Piriformospora indica increase grain yield and P content in wheat. Plant Soil 2018, 426, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzebisz, W.; Potarzycki, J.; Biber, M.; Szczepaniak, W. Reakcja roślin uprawnych na nawożenie fosforem. J. Elem. 2003, 8, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Haneklaus, S.H.; Schnug, E. Assessing the plant phosphorus status. In Phosphorus in Agriculture: 100 % Zero; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 95–125. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu, A.S.; Fageria, N.K.; Berni, R.F.; Rodrigues, F.A. Phosphorus and plant disease. In Mineral Nutrition and Plant Disease; American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2007; pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, K. Phosphorus solubilizing bacteria: Occurrence, mechanisms and their role in crop production. Resour. Environ. 2012, 2, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Weigand, H.; Bertau, M.; Hübner, W.; Bohndick, F.; Bruckert, A. RecoPhos: Full-scale fertilizer production from sewage sludge ash. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kauwenbergh, S.J.; Stewart, M.; Mikkelsen, R. World reserves of phosphate rock… a dynamic and unfolding story. Better Crops 2013, 97, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tenkorang, F.; Lowenberg-Deboer, J. Forecasting long-term global fertilizer demand. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2009, 83, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, D.; White, S. Peak phosphorus: Clarifying the key issues of a vigorous debate about long-term phosphorus security. Sustainability 2011, 3, 2027–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schroder, J.J.; Cordell, D.; Smit, A.L.; Rosemarin, A. Sustainable use of Phosphorus: EU Tender ENV. B1/ETU/2009/0025; Plant Research International: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rosemarin, A.; Jensen, L.S. The phosphorus challenge. In Proceedings of the European Sustainable Phosphorus Conference, Brussels, Belgium, 6–7 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- USGS. Mineral Commodity Summaries 2019. Phosphate Rock; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2019; pp. 122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Geissler, B.; Mew, M.C.; Steiner, G. Phosphate supply security for importing countries: Developments and the current situation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 677, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. Report on critical raw materials for the EU. European Commission. In Report of the Ad-Hoc Working Group on Defining Critical Raw Materials; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Jaskulski, D.; Jaskulska, I. Possibility of using waste from the polyvinyl chloride production process for plant fertilization. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2011, 20, 351–354. [Google Scholar]

- Smol, M.; Kulczycka, J.; Kowalski, Z. Sewage sludge ash (SSA) from large and small incineration plants as a potential source of phosphorus—Polish case study. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 184, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staroń, A.; Kowalski, Z.; Banach, M.; Wzorek, Z. Sposoby termicznej utylizacji odpadów z przemysłu mięsnego. Czas. Tech. Chem. 2010, 107, 323–332. [Google Scholar]

- Saeid, A.; Labuda, M.; Chojnacka, K.; Górecki, H. Use of microorganisms in the production of phosphorus fertilizers. Przem. Chem. 2012, 91, 956–958. [Google Scholar]

- Karpagam, T.; Nagalakshmi, P.K. Isolation and characterization of phosphate solubilizing microbes from agricultural soil. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 601–614. [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi, R.; Tewari, R.; Nayyar, H. Synergy between plants and P-solubilizing microbes in soils: Effects on growth and physiology of crops. Int. Res. J. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 484–503. [Google Scholar]

- El-Komy, H.M.A. Coimmobilization of Azospirillum lipoferum and Bacillus megaterium for successful phosphorus and nitrogen nutrition of wheat plants. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2005, 43, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Saeid, A.; Prochownik, E.; Dobrowolska-Iwanek, J. Phosphorus solubilization by Bacillus species. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Etesami, H.; Beattie, G.A. Mining halophytes for plant growth-promoting halotolerant bacteria to enhance the salinity tolerance of non-halophytic crops. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nesme, T.; Withers, P.J.A. Sustainable strategies towards a phosphorus circular economy. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosys. 2016, 104, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saeid, A.; Wyciszkiewicz, M.; Jastrzebska, M.; Chojnacka, K.; Gorecki, H. A concept of production of new generation of phosphorus-containing biofertilizers. BioFertP project. Przem. Chem. 2015, 94, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolewicz, M.; Rusek, P.; Borowik, K. Obtaining of granular fertilizers based on ashes from combustion of waste residues and ground bones using phosphorous solubilization by bacteria Bacillus megaterium. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 216, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, U. Growth Stages of Mono- and Dicotyledonous Plants: BBCH-Monograph; Blackwell Wissenschafts-Verlag: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 1997; p. 622. [Google Scholar]

- World Reference Base (WRB); IUSS Working Group. World reference base for soil resources 2014. In International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2014; update 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.P. Use of acid, rose bengal, and streptomycin in the plate method for estimating soil fungi. Soil Sci. 1950, 69, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.B. Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes; CMI: Kew, UK, 1971; p. 608. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, J.F.; Summerell, B.A. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 1–388. [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Pẽa, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edgar, R.C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2460–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Larsson, K.H.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Jeppesen, T.S.; Schigel, D.; Kennedy, P.; Picard, K.; Glöckner, F.O.; Tedersoo, L.; et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: Handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D259–D264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatSoft, I. Statistica (Data Analysis Software System), Version 13; Statsoft Inc.: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, L.; Friendly, M. History corner the history of the cluster heat map. Am. Stat. 2009, 63, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, J.H., Jr. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.J.; Morgan, P.; Weightman, A.J.; Fry, J.C. Cultivation-dependent and -independent approaches for determining bacterial diversity in heavy-metal-contaminated soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 3223–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Littlefield-Wyer, J.G.; Brooks, P.; Katouli, M. Application of biochemical fingerprinting and fatty acid methyl ester profiling to assess the effect of the pesticide Atradex on aquatic microbial communities. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 153, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankina, B.; Bimšteine, G.; Neusa-Luca, I.; Roga, A.; Fridmanis, D. What influences the composition of fungi in wheat grains? Acta Agrobot. 2017, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, K.G.; Jiang, Y.M.; Li, Y.K.; Xu, Q.Q.; Niu, J.S.; Zhu, X.X.; Li, Q.Y. Identification and pathogenicity of fungal pathogens causing black point in wheat on the North China Plain. Indian J. Microbiol. 2018, 58, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suproniene, S.; Mankevičiene, A.; Kadžiene, G.; Kačergius, A.; Feiza, V.; Feiziene, D.; Semaškiene, R.; Dabkevičius, Z.; Tamošiunas, K. The impact of tillage and fertilization on Fusarium infection and mycotoxin production in wheat grains skaidre suproniene. Zemdirbyste 2012, 99, 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens, M.; Haim, K.; Lew, H.; Ruckenbauer, P. The effect of nitrogen fertilization on Fusarium head blight development and deoxynivalenol contamination in wheat. J. Phytopathol. 2004, 152, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, J.; Alikhani, H.A.; Etesami, H.; Pourbabaei, A.A. Improved phosphorus uptake by wheat plant (Triticum aestivum L.) with rhizosphere fluorescent Pseudomonads strains under water-deficit stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ervin, E.H.; Evanylo, G.K.; Haering, K.C. Impact of biosolids on hormone metabolism in drought-stressed tall fescue. Crop Sci. 2009, 49, 1893–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.S.; Riaz, M.; Shahzad, S.M.; Yasmeen, T.; Ali, S.; Akhtar, M.J. Phosphorus-mobilizing rhizobacterial strain Bacillus cereus GS6 improves symbiotic efficiency of soybean on an aridisol amended with phosphorus-enriched compost. Pedosphere 2017, 27, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S.; Zhang, W.; Guan, Y.; et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 2012, 490, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protein Database. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Proteins. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein (accessed on 7 July 2018).

- Jarolim, K.; Del Favero, G.; Pahlke, G.; Dostal, V.; Zimmermann, K.; Heiss, E.; Ellmer, D.; Stark, T.D.; Hofmann, T.; Marko, D. Activation of the Nrf2-ARE pathway by the Alternaria alternata mycotoxins altertoxin I and II. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Menzies, J.G. Virulence of isolates of Ustilago tritici collected in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, Canada, from 1999 to 2007. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 38, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajska, J.; Wachowska, U. Characterization of binucleate isolates of Rhizoctonia cerealis with respect to cereals. In Proceedings of the Symposium on New Direction in Plant Pathology, Kraków, Poland, 11–13 September 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Weidenbörner, M. Mycotoxin contamination of cereals and cereal products. In Mycotoxins in Plants and Plant Products; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–715. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan, V.; Selvaraj, G.; Bais, H.P. Functional soil microbiome: Belowground solutions to an aboveground problem. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschen, R.; Hunt, S.; Mykura, C.; Gange, A.C.; Sutton, B.C. The foliar endophytic fungal community composition in Cirsium arvense is affected by mycorrhizal colonization and soil nutrient content. Fungal Biol. 2010, 114, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellissier, L.; Oppliger, A.; Hirzel, A.H.; Savova-Bianchi, D.; Mbayo, G.; Mascher, F.; Kellenberger, S.; Niculita-Hirzel, H. Airborne and grain dust fungal community compositions are shaped regionally by plant genotypes and farming practices. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 2121–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| P-Fertilizer | P2O5 Rate, kg ha−1 | Treatment Symbol | Fertilizer Characteristics (Elemental Composition of Fertilizers) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 | C0 | No P fertilization |

| Superphosphate | 40 | SP40 | FosdarTM40 commercial superphosphate fertilizer (P2O5 40%; CaO 10%; SO3 5%; trace presence: Fe, Zn, Cu, B, Co, Mn, Mo) 1 |

| 60 | SP60 | ||

| 80 | SP80 | ||

| Recycled fertilizer | 40 | Rec40 | Granular fertilizer made from ash from the incineration of biological sewage sludge (third level of treatment), and dried animal blood (P2O5 19.9%; N 2.89%; K2O 1.31%; CaO 18.71%; MgO 2.56%; SO3 1.40%; C 13.92%, Fe 27 g kg−1; Al 23.8 g kg−1; Zn 3.14 g kg−1; As 31.39 mg kg−1; Cd < LD; Cu 777.7 mg kg−1; Ni 54.78 mg kg−1, Pb 19.91 mg kg−1; B 71.27 mg kg−1; Ba 349.6 mg kg−1; Co 14.02 mg kg−1; Mn 561.7 mg kg−1; Mo 35.31 mg kg−1) 2 |

| 60 | Rec60 | ||

| 80 | Rec80 | ||

| Recycled biofertilizer | 40 | Bio40 | Granular biofertilizer made from sewage sludge ash (as above), dried animal blood, and cultured Baccilus megaterium (P2O5 21.9%C; N 2.87%; K2O 1.40%; CaO 20.51%; MgO 2.82%; SO3 1.40%; C 13.92%; Fe 29.0 g kg−1; Al 25.5 g kg−1; Zn 3.29 g kg−1; As 19.99 mg kg−1; Cd 0.345 mg kg−1; Cu 850.1 mg kg−1; Ni 62.65 mg kg−1. Pb 21.76 mg kg−1; B 74.12 mg kg−1; Ba 381.5 mg kg−1. Co 16.19 mg kg−1; Mn 609.4 mg kg−1; Mo 23.75 mg kg−1)2 |

| 60 | Bio60 | ||

| 80 | Bio80 |

| Pesticide Type | Trade Name (Manufacturer) | Active Ingredient (g dm−3) | Rate (dm3 ha−3) | Application Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herbicides | Mustang 309 SE (Dow AgroSciences 1) | Florasulam (6.25) + 2,4-D (300) | 0.5 | Flag leaf stage (BBCH 39; 29 May) |

| Fungicides | Yamato 303 SE (Sumi Agro 1) | Thiophanate-methyl (233) + Tetraconazole (70) | 1.5 | Early boot stage (BBCH 41; 9 June) |

| Amistar 250 SC (Syngenta 1) | Azoxystrobin (250) | 0.8 | End of flowering (BBCH 69; 8 July) | |

| Insecticides | Karate Zeon 050 CS (Syngenta 1) | Lambda-cyhalothrin (50) | 0.1 | Early boot stage (BBCH 41; 6 June) |

| P-Treatment | Total P, mg kg−1 |

|---|---|

| C0 | 540.3 ± 5.9 |

| SP40 | 590.7 ± 18.1 |

| SP60 | 603.1 ± 9.7 |

| SP80 | 612.9 ± 23.9 |

| Rec40 | 604.3 ± 4.7 |

| Rec60 | 613.2 ± 11.9 |

| Rec80 | 626.3 ± 36.6 |

| Bio40 | 597.4 ± 17.7 |

| Bio60 | 611.2 ± 16.4 |

| Bio80 | 621.5 ± 13.7 |

| P-Treatment | Alternaria spp. | Fusarium culmorum | Fusarium poae | Fusarium graminearum | Fusarium avenaceum | Fusarium solani Species Complex | Other 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log (CFU + 1) per 1 g of grain | |||||||

| C0 | 0 d | 0 c | 1.28 a | 0.35 bc | 0 c | 0 | 0 b |

| SP40 | 1.23 abc | 0.84 abc | 0 b | 0.94 ab | 0.35 bc | 0 | 0 b |

| SP60 | 0.44 cd | 0 c | 1.42 a | 1.19 a | 0 c | 0 | 0 b |

| SP80 | 1.38 abc | 1.57 a | 0 b | 0.35 bc | 0 c | 0 | 0 b |

| Rec40 | 1.23 abc | 1.04 ab | 0 b | 0 c | 0 c | 0 | 0 b |

| Rec60 | 0.35 d | 0.69 abc | 0 b | 0 c | 0 c | 0 | 0 b |

| Rec80 | 0.44 cd | 0.35 bc | 0 b | 1.43 a | 0 c | 0.44 | 0 b |

| Bio40 | 1.64 a | 0.88 abc | 0 b | 1.49 a | 0.69 ab | 0 | 0 b |

| Bio60 | 1.03 abc | 1.19 ab | 0 b | 1.33 a | 0 c | 0 | 0 b |

| Bio80 | 1.48 a | 0.35 bc | 0 b | 1.40 a | 1.04 a | 0 | 1.14 a |

| P-Treatment | Yeasts | Mycosphaerella tassiana | Acremonium spp. | Mucor spp. | Aspergillus spp. | Penicillium spp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log (CFU + 1) per 1 g of grain | ||||||

| C0 | 2.58 ab | 2.41 abc | 1.55 abc | 0 | 0.44 ab | 0 b |

| SP40 | 2.55 ab | 2.56 abc | 1.76 abc | 0.34 | 1.04 a | 0 b |

| SP60 | 2.64 ab | 2.33 c | 1.84 abc | 0 | 0.35 b | 0 b |

| SP80 | 2.34 b | 2.05 c | 0.94 c | 0 | 0 b | 2.21 a |

| Rec40 | 2.75 ab | 2.20 c | 1.97 ab | 0 | 0 b | 0 b |

| Rec60 | 2.62 ab | 2.71 a | 1.38 abc | 0 | 0 b | 0 b |

| Rec80 | 2.79 ab | 2.35 c | 2.33 a | 0 | 0 b | 0 b |

| Bio40 | 2.84 a | 2.56 abc | 1.18 bc | 0 | 0 b | 0 b |

| Bio60 | 2.79 ab | 2.64 ab | 2.34 a | 0 | 0 b | 0 b |

| Bio80 | 2.87 a | 2.54 abc | 1.92 ab | 0 | 0.35 b | 0 b |

| P-Treatment | Alternaria spp. | Fusarium avenaceum | Fusarium graminearum | Fusarium poae | Fusarium sporotrichioides | Epicoccum nigrum | Botrytis cinerea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0 | 20.37 | 5.56 | 1.85 | 5.56 | 1.85 | 1.85 | 0 |

| SP40 | 16.67 | 5.56 | 0 | 1.85 | 7.41 | 0 | 1.85 |

| SP60 | 24.07 | 1.85 | 0 | 3.70 | 7.41 | 0 | 0 |

| SP80 | 14.81 | 3.70 | 3.70 | 5.56 | 0 | 1.85 | 1.85 |

| Rec40 | 14.81 | 1.85 | 0 | 5.57 | 1.85 | 3.70 | 0 |

| Rec60 | 25.93 | 3.70 | 0 | 0 | 3.70 | 0 | 0 |

| Rec80 | 27.78 | 0 | 1.85 | 3.70 | 1.85 | 0 | 0 |

| Bio40 | 25.93 | 0 | 0 | 1.85 | 3.70 | 0 | 0 |

| Bio60 | 22.22 | 0 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 | 5.56 | 0 |

| Bio80 | 20.37 | 0 | 0 | 3.70 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P-Treatment | Alternaria spp. | Fusarium avenaceum | Fusarium graminearum | Fusarium oxysporum | Fusarium poae | Fusarium solani Species Complex | Fusarium sporotrichioides | Epicoccum nigrum | Botrytis cinerea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0 | 27.78 | 0 | 3.70 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 | 0 b | 1.85 | 0 |

| SP40 | 24.07 | 1.85 | 1.85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.85 ab | 1.85 | 1.85 |

| SP60 | 18.52 | 0 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 b | 0 | 1.85 |

| SP80 | 22.22 | 3.70 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 | 0 | 0 b | 0 | 0 |

| Rec40 | 31.48 | 3.70 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 b | 0 | 0 |

| Rec60 | 29.63 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.70 | 0 | 0 b | 0 | 0 |

| Rec80 | 29.63 | 1.85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.85 ab | 0 | 0 |

| Bio40 | 18.52 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.56 a | 1.85 | 0 |

| Bio60 | 25.93 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 | 0 b | 0 | 0 |

| Bio80 | 24.07 | 1.85 | 1.85 | 0 | 1.85 | 0 | 1.85 ab | 0 | 0 |

| Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genus | C0 * | SP40 | SP60 | SP80 | Rec40 | Rec60 | Rec80 | Bio40 | Bio60 | Bio80 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomycota | Dothideomycetes | Pleosporales | Pleosporaceae | Alternaria | 67.58 | 78.49 | 83.75 | 49.99 | 89.68 | 95.35 | 66.21 | 81.5 | 70.61 | 71.05 |

| Pyrenophora | 0.33 | 0 | 0.54 | 2.59 | 1.73 | 0 | 3.33 | 2.41 | 5.89 | 2.46 | ||||

| Bipolaris | 0 | 1,7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Stemphylium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Capnodiales | Mycosphaerellaceae | Mycosphaerella | 2.15 | 1.22 | 1.49 | 1.64 | 1.11 | 0.61 | 5.58 | 0.66 | 1.01 | 8.23 | ||

| Sordariomycetes | Xylariales | Amphisphaeriaceae | Monographella | 11.97 | 0 | 1.82 | 4.17 | 0.88 | 0.27 | 7.14 | 2.57 | 2.85 | 0 | |

| Hypocreales | Nectriaceae | Gibberella | 1.6 | 1.22 | 0.94 | 4.5 | 3.06 | 0.62 | 2.9 | 0.62 | 4.45 | 5.49 | ||

| Fusarium | 0 | 0.56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.76 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Cordycipitaceae | Lecanicillium | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.23 | |||

| Leotiomycetes | Helotiales | Sclerotiniaceae | Botrytis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Basidiomycota | Tremellomycetes | Filobasidiales | Filobasidiaceae | Filobasidium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.19 |

| Ustilaginomycetes | Ustilaginales | Ustilaginaceae | Ustilago | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Anthracocystis | 0.76 | 0 | 0.72 | 0 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jastrzębska, M.; Wachowska, U.; Kostrzewska, M.K. Pathogenic and Non-Pathogenic Fungal Communities in Wheat Grain as Influenced by Recycled Phosphorus Fertilizers: A Case Study. Agriculture 2020, 10, 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10060239

Jastrzębska M, Wachowska U, Kostrzewska MK. Pathogenic and Non-Pathogenic Fungal Communities in Wheat Grain as Influenced by Recycled Phosphorus Fertilizers: A Case Study. Agriculture. 2020; 10(6):239. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10060239

Chicago/Turabian StyleJastrzębska, Magdalena, Urszula Wachowska, and Marta K. Kostrzewska. 2020. "Pathogenic and Non-Pathogenic Fungal Communities in Wheat Grain as Influenced by Recycled Phosphorus Fertilizers: A Case Study" Agriculture 10, no. 6: 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10060239

APA StyleJastrzębska, M., Wachowska, U., & Kostrzewska, M. K. (2020). Pathogenic and Non-Pathogenic Fungal Communities in Wheat Grain as Influenced by Recycled Phosphorus Fertilizers: A Case Study. Agriculture, 10(6), 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10060239