Appropriation of Caste Spaces in Pakistan: The Theo-Politics of Short Stories in Sindhi Progressive Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

The Harijan lives like dead soul, having accepted all the exploitation and atrocities as their destiny. They might develop a defiant attitude against these injustices but it remains confined to their minds. On the contrary, Ambedkar’s Dalit is audacious, courageous and infused with zeal and zest to fight against exploitation and live with dignity. His rebel doesn’t just imagine being one but steps into the real world.

3. Situating Short Stories in Sindhi Progressive Literature

Once, [Pishu] passed by the guest of house Raes Gul Khan. He was dying of thirst. Without caring for consequences, he entered the guest house and grabbed the glass of Raes Gul Khan. All present on the scene tried to stop him, saying, ‘Nope, Nope!; But, by that time this gentleman had drunk two-three glasses of water. Putting down the glass, [Pishu] said ‘Brother why affront!Did that glass belong to any Chuhra?’

4. The Reframing of ‘Infidel’ to Uphold Interfaith Harmony

Mukhi, the panchayat headman of Oad [Dalit] community begged in the name of holy Gita and even threw his turban at Seetal’s feet, but Seetal just didn’t care much and replied:“Mukhi! Do whatever you like, but I shall change my religion.Mukhi: But why after all you want to change your religion?Seetal: My choice, my wish simply.Mukhi: Even then?Seetal: I just don’t like my religion. That’s it.Mukhi: Alas! Why on earth don’t you like your religion?Seetal: Alright Mukhi. Tell me, who are we?Mukhi: We are Hindus.Seetal: Why then Hindus cremate the dead, whereas we bury them?Mukhi: It’s our ritual.Seetal: Alright. Why do we eat goat after butchering it (like Muslims)?Mukhi: This too is our ritual—since the times of old ancestors.Seetal: But these are the rituals of Muslims?Mukhi: These are theirs. But ours too!!Seetal: Then how can you say, we are Hindus?Mukhi: Then what the heck are we, crank?Seetal: Half Hindus-half Muslim. (We have) body of sheep, head of goat.”

One the one hand we surpass all limits of exaggeration and slogan mongering to prove that there is not caste system in Islam and on the other, in reality, we are the leading custodians of the system of untouchability and casteism.(Rasool Bux Paleejo in Memon 2002, p. 346)

I remember for sure that it was the night of 11 December 1977, when I met at Hemandas’ home. I had a chit chat with Kanji Mal (officer national bank), Ganesh Balani, Bhani Mal, Sarvan Kumar, Naraern and Heman [all Dalits of Meghwar caste]. If I remember correctly, either Ganesh Mal (or any of the friends present) put up a proposal that ‘we Meghwar are considered as lower-class Hindus, by caste Hindus. Therefore, our survival lies in converting to Islam’. There, I opposed that thinking that it is not the solution, because caste-based class discrimination also exists among Muslims. No Sayed Muslim will allow marry his daughter into any other caste, not to mention of Machi Muslim (fisherman caste considered the lower among Muslims). Although the days have much changed now, but even then, I narrated them the fiction story (based on social reality of casteism among Muslims) of Naseem Kharal.

Finally, we came to a consensus that the solution of social discriminations lies in education and only education. Today I feel proud that it is the effect of my ideas and the fiction story of Naseem Kharal narrated by me, that Ganesh Balani’s four daughters have now reached the highest educational achievement: Shabnam Rathore made Sindh famous by doing PhD from Germany in ‘Underground Saline Water’. Another Pushpa Kumari has done M.Sc. from Agricultural University Tando Jam. Third daughter Nimrita, is a lecturer in Sindh University’s microbiology department. Fourth Sushhma Devi who did M.Sc from botany and serving as lecturer in Karachi.(Taj Joyo, Preface to Hemanda Chandani’s Humerche Hoongar, p. 12)

5. Invoking Self-Pity in ‘Dust of Earth and Stars of Sky’

The emotions of the youthful age cannot be controlled by the systems of caste or religion. The people of Rohri town could not escape the gorgeous youthful spark of Bali. Her startling beautiful body could barely be hid under her tattered clothes.(Jaleel, pp. 68–69)

‘And Sisters?’ [‘What did they do?’ asked Shahu]‘They were harlots’ (p. 74)[…]‘The eldest eloped with a Punjabi rascal…and he engaged her in prostitution’‘The younger one eloped with a Baloch to Shikarpur’… ‘A few days later there was corpse of my sister lying on the river bank’. (p. 75)

‘Junior Shah! Hope you are fine’ [Teachers greeted Shahu while he having whisky]‘Fine, need your prayers’ Shahu replied coldly.

‘Why are you making we ummatis [subjects of yours] sinner’. One of the teachers even pleaded before him, saying, ‘We solely rely on you for our wellbeing here and in the hereafter’.Shahu remained utterly disinterred towards teacher’s pleadings. (p. 80)

[Bali] ‘I am not even a Muslim’[Shahu], ‘I am Sayed, who truly deserves to be in paradise’. He dragged her to herself, ‘In Islam the greatest of bounty is to convert any non-Muslim to Islam. I will make you Muslim’.

… ‘I will marry you and teach you how to behave in Ashrafia family’. … ‘Leave knitting nets.’…Bali gradually slid her face on the breast of Shahu, and said ‘I will leave knitting nets’. (pp. 84–85)

[Shahu’s friend Siraj] ‘Uncountable children of the Ashrafia are begotten and brought up this way among the Bheel’. Siraj tried to console Shahu, ‘Why do you worry so much’.‘I am Sayed Siraj’ Shahu rebutted in hard accent. (p. 88)

‘Humiliation terrifies the honorable. Not to the worthless Bheel women who does not know about what dignity is’. (p. 89)

‘You, the despicable, lower caste, you are a worthless Bheel’. Shahu grabbed her from her plait and said, ‘and do you know, I am Sayed, Sayed am I’. (p. 93)‘We do not even let our ummatis [Muslim subjects] to get so close to us, and this infidel Bheel dreams of marrying a Sayed’. (p. 94)

He was consoling himself that he was killing a newborn daughter in the name of God, to save a Sayed child from wandering among the Bheels. In the afterlife, God will give him his due reward. In case it did not happen as planned, then at least he had that genealogical capital of being Sayed to intercede before God. (p. 101)

There is a specific nature of the honor and the respect of Sayeds in Sindh, whereby people confer upon them the status of Murshid (spiritual leaders), and consider them as the continuation of Prophet Muhammad’s progeny, and to themselves as ‘ummatis’ (social subjects of Sayeds) thus assigning themselves lower status. No doubt, the respect for Sayeds in its own way is justified, but there have been Sayeds in history who has taken an undue advantage of that status. After the coming of modern progressive wave, the thinking has evolved not to discriminate on the caste and race.

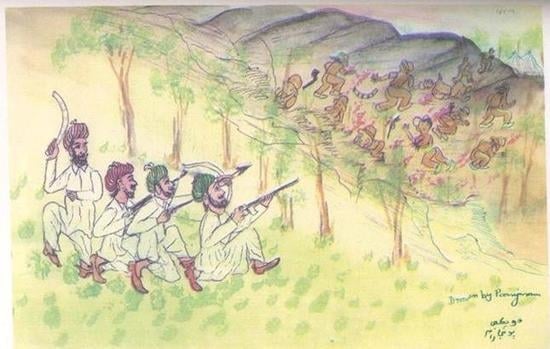

6. ‘The Prisoner of Karoonjhar’ and the Appropriation of Dalit Heroes and Spaces

As if the British canons were roaring. […] As if hearts of Samma, Soadha, Soomra, Thakur, Rabari and Kolhi women were being ripped asunder. […] Rano, Tkhakur, Khoso, Rathore, Samon, Soomro, Parmar and Kohli all had sacrificed their lives for the sake of Karoonjhar (p. 14).[…][The battle was not over yet] the English would trigger the canons because Ranas [Sodha Thakur rulers of Parkar] has not given up yet. Thousands of Kolhi, Bheel, Rathore, Samma and Khosa were roaming secretly in the valleys of Karoonjhar Mountain (pp. 14–15)[…]No sooner did that night fall, Kolhis would began attacking the pickets of the British army. […] The British did not confront such kind of rebellion in any other part of the Hindustan […]. When captain Tyrwhitt received an indictment from Sir Charles Napier, he simply sent a reply, ‘I regret. Here we are not fighting with the people but with the terrifying volcanic mountain’. The poor captain Trywhitt felt himself at his wits ends. He was unable to devise any way to control Ranas (Sodha Thakurs) and Kolhis (p. 15).[…]

That Kolhi was tall and dark brown like the Shri Kirshan Mahrarj of Hindu sacred books, and as resolved and steadfast as Arjun Maharaj (p. 15)[The British new that whom they were fighting with]‘Roopa [Rooplo Kolhi] we do not want to kill you. You just simply tell us the whereabouts of Ladhoo Singh and his accomplices. We will confer upon you the fief as per your desire’.[The writer begins reframing Rooplo as the self-motivated fighter who damn cares about Ladhoo Singh]‘This whole land is mine. Who the hell are you to give that back as a fief to me?’

‘Were you not a slave of Rana Ladhoo Singh?’‘No, I would have shoot Ladhoo Singh, if I had felt that I were a slave of him’ (p. 19).

‘Roopa, I have come to see you the last time. Never ever make me the object of ridicule before Kolhi women. Never give up. Otherwise, I shall abandon you. Moving her hand over the pregnant belly I shall proclaim that this child is not begotten of Rooplo, but of someone else’ (p. 17)

‘They were Ladhoo Singh and Rooplo, from whom you had escaped to seek refuge under the tannery of Meghwars’ [p. 18]

For the first time, Trywhitt felt that no alien nation can occupy the lands of foreign nation for more than 25 years, but they might be compelled to vacate Karoonjhar probably even before 12 years.

By having a look on the overall scenario during that period, it becomes evident that it was the period during which to remain loyal to the local ruler under the given tribal system was considered as loyalty to the nation. By and large the same kind of struggles can be evidenced during Mughal era against British.

Mado Meghwar, who gave refuge to Trawat [Tyrwhitt24]. Do you know why he gave refuge to tarawat? Very few know. You must see, during that period, the poor classes… in 1800s.the first Dalit woman who wrote a letter…she only was class VIII pass. She was … Savatri Bai Phule… she writes that they were the English people who came in and freed us from clutches of the upper castes. They see the coming of the British as the precursor of emancipation. They supported the British during the 1857 war, the Sikhs allied with the British to get rid of Mughal persecution. Similarly, Meghwar like Madhu, and the people of Parkar, particularly Dalits, sided with the British as the emancipators who got them rid of the domination of Sodha Thakurs. And this [Rooplo], who was the paid mercenary of Sodha Thakurs, is now reckoned as the hero in history. But those like Madhoo Meghwar who supported the British to get rid of Sodhas persecutors are condemned as the rebels.

Thari people have unique instinct of liking and making heroes for themselves. Mughal Emperor Akbar was a legendary figure for them only second to local deities, so was General Taroot (Tyrwhitt). Despite the fact that Taroot was the one who overwhelmed Sodha Rajputs and hanged Rooplo Kolhi, he was highly praised and eulogized by Tharis in folk songs, and folklore during and after Taroot’s times.

‘To be Kolhi is the matter of pride. Civilization cannot be erected by becoming Sayed.’(Sardar Shah)

‘I will try to convince my party leadership to ensure representation of Kolhi community in the parliament.’26(Sardar Shah)

‘Rooplo Kolhi fought the battle against the British forces for the Sindh, and sacrificed his life. The youth should follow the example’.Nawab Yousaf Talpur

‘We are proud of Rooplo Kolhi. He fought the war for the survival of Sindh’.Nawab Taimur Talpur (MPA)27

‘Rooplo Kolhi memorials will be built in each major city including Karachi’.(Ibrat daily, Sindhi newspaper)

‘The Dravidians and politicians of Sindh declared immortal Rooplo Kolhi, the son of the soil.’28

The 159th anniversary of Shaheed Rooplo Kolhi was celebrated by Jeay Sindh Mahaz at Sachal village, Karachi. Chairman of Mahaz, Abdul Khaliq Junejo said that Raja Dahar, Hoshoo Sheedi and Rooplo Kolhi are our valiant heroes, and that Muhammad-bin-Qasim is historically condemned as the imperialist. He said that the anniversaries of Rooplo are being celebrated lately by the ruling elites since the last two-three years to appropriate Rooplo for their vested interests. But they must remember that the resistance of Rooplo was not simply for capturing seat in legislative assembly or to appease any specific sect, but for his land Sindh, the legacy of which rule-hungry elite cannot be the inheritors.(Ranshal Kolhi, Facebook Status, 24th August 2019)

It’s not just that simple, that democracy fascinates Dalits. Under it, they eagerly sell out their heroes to nationalists, and give away their gods to Brahmins and Lohanas; they are willing to banish all their ancestral gods to exclusively worship Ram, Krishana and Ganesha.(A Dalit activist, Personal Interview, 2016)

This was apolitical anniversary. In this anniversary there was no minister, advisor or senator. Despite that the sea of people flooded in, which proves that people have now do not accept this waderko-bhotarko (feudal) system.

A decade after Rooplo’s martyrdom, in 1964 when the British was still there in Parkar, the incident happened in Holi Garho in Pithapur where Thakurs of Dedhvero, and Khosas of Kabri31 attacked the Chatro Kolhi and his son (would-be groom). Thereafter, many Kolhis decided to leave Parkar migrate to Barrage area of Sindh to settle there permanently instead of returning back seasonally32.Top of Form

7. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abro, Jamal. 2015. Pishu Pasha aen Biyon Kahariyon. Kandiaro: Roshni Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, Irfan. 2003. A Different Jihad: Dalit Muslims’ Challenge to Ashraf Hegemony. Economic and Political Weekly. pp. 4886–91. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4414283 (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. 2014. Dr. Babasaheb B. Ambedkar, Writings and Speeches; Edited by Vasant Moon. New Delhi: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India, vol. 1–9. Available online: http://www.mea.gov.in (accessed on 8 March 2019)First published 1991.

- Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. 2014. Annihilation of Caste: The Annotated Critical Edition. London: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York and London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, Ali. 1994. Munhjiyoon Kahariyoon. Roshni Publication (First Edition), Digital Edition (2018) by Sindh Salamat Ghar. Available online: https://books.sindhsalamat.com/book.php?book_id=736 (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Behdad, Ali, and Dominic Thomas. 2011. A Companion to Comparative Literature. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bheel, Ganpat Rai. 2017. Journey of a Dalit Corpse. Translated by Ghulam Hussain. Rountable India. Available online: https://roundtableindia.co.in (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Buehler, Arthur F. 2012. Trends of ashrafization in India. In Sayyids and Sharifs in Muslim Societies: The Living Links to the Prophet. Edited by Morimoto Kazuo. London: Routledge, pp. 231–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chandio, Jami. 2016. Sandi Jogiyan Zaat. Karachi: Peacock Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- CIFORB. 2018. Forced Conversions & Forced Marriages in Sindh, Pakistan. Birmingham: The University of Birmingham. [Google Scholar]

- Damrosch, David. 2009. How to Read World Literature. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Eagleton, Terry. 2002. Marxism and Literary Criticism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gramsci, Antonio. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. New York: International Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Guru, Gopal, and Sundar Sarukkai. 2012. The Cracked Mirror: An Indian Debate on Experience and Theory. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guru, Gopal. 1995. Dalit women talk differently. Economic and Political Weekly 30: 2548–50. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4403327 (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Guru, Gopal. 2000. Dalits in Pursuit of Modernity. In India: Another Millennium? New Delhi: Penguin India, pp. 123–37. [Google Scholar]

- Guru, Gopal. 2011a. Liberal Democracy in India and the Dalit Critique. Social Research: An International Quarterly 78: 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guru, Gopal. 2011b. The Idea of India: ‘Derivative, Desi and Beyond’. Economic and Political Weekly 46: 36–42. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23047279 (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Hussain, Ghulam. 2018. Legitimacies of Caste Positions in Pakistan: Resolving ‘upper caste’ delimma in shared space of knowledge production and emancipation. Panjab University Reserach Journal (Arts) XLV: 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Ghulam. 2019a. Understanding Hegemony of caste in political Islam and Sufism in Sindh, Pakistan. Journal of Asian and African Studies 54: 716–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Ghulam. 2019b. ‘Dalits are in India, not in Pakistan’: Exploring the Discursive bases of the Denial of Dalitness under the Ashrafia Hegemony. Journal of Asian and African Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Ghulam. 2019c. Dalit Adab (April-May and June-July Editions). Mendeley Data, V2, [Unpublished online personal archive]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Ghulam. 2019d. Dalit Adab (Pre-prints by Ganpat Rai Bheel). Mendeley Data, V1, [Unpublished online personal archive]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Ghulam. 2019e. Articles and Books of Ganpat Rai Bheel. Mendeley Data, V1, [Unpublished online personal archive]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Fahmida. 1997. Adabi Tanqeed, Fann aen Tareekh. Karachi: Sindh Adabi Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Ilaiah, Kancha. 2010. The Weapon of the Other: Dalitbahujan Writings and the Remaking of Indian Nationalist Thought. Chennai: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel, Amar. 1998. Dil Ji Dunya. Kandiaro: Roshni Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel, Amar. 2007. Ranni Kot jo Khazano. Davao City: New Fields. [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel, Amar. 2010. Lahandar Sijj Ji Laam. Karachi: Katcho Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel, Amar. 2012. Jeejal Munhji Mau. Karachi: Kactho Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Junejo, Abdul Jabar. 2004. Sindhi Adab Ji Mukhtasir Tareekh, 1st ed. Hyderabad: Sindhi Language Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Junejo, Abdul Qadir. 2010. Dar Dar Ja Musafir. Kandiaro: Roshini Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Junejo, Faiz. 2015. “Tabqati Fikir Ja Sindhi Adab Tey Asar” [Sindhi]. Karachi: Sindh Sudhar Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kazuo, Marimoto. 2004. Toward the Formation of Sayyido-Sharifology: Questioning Accepted Fact. The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies 22: 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kolhi, Bhooro Mal. 2014. Paracheen Lok: Ekweeheen Sadi Jey Aaeeney Mein, 1st ed. Hyderabad: Himat Printers and Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kolhi, Veerji. 2011. 152nd Death Anniversary of a National Hero Defender of his Motherland, Amar Rooplo Kohli. Retrieved from Veerji Kolhi: A Social Activist. Available online: http://veerji-kolhi.blogspot.com/2011/08/152nd-death-anniversary-of-national.html (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- Kothari, Rita. 2001. Short Story in Gujarati Dalit Literature. Economic and Political Weekly 36: 4308–11. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4411356 (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Kothari, Rita. 2009. Unbordered Memories: Sindhi Stories of Partition. New Delhi: Penguine Groups. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Vivek. 2016a. Caste, Contemporaneity and Assertion. Economic and Political Weekly 51: 48–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Vivek. 2016b. How Egalitarian Is the Indian Sociology. Economic and Political Weekly 51: 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Vivek. 2018. Locating Dalit Perspective of Social Reality. International Journal of Indigenous and Marginal Affairs 4: 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kumbhojkar, Shraddha. 2012. Contesting Power, Contesting Memories: The History of the Koregaon Memorial. Economic and Political Weekly 47: 103–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, Asmita, and Shukla Maitreyee. 2017. Et Tu ‘Feminists’?: A response to the Kafila signatories. Roundtale India, Roundtable India. Retrieved October 28, 2017. Available online: https://roundtableindia.co.in (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Lata, Prabhita Madhukar. 2015. Silenced by Manu and ‘Mainstream’ Feminism: Dalit-Bahujan Women and their History. Roundtable India. Retrieved October 4, 2017. Available online: https://roundtableindia.co.in (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Levesque, Julien, and Camille Bui. 2014. Umar Marvi and the Representation of Sindh: Cinema and Modernity in the Margins. BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies 5: 119–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mal, Paru. 2000. Lok Sagar Ja Moti. Mirpurkhas: Parkari Audio Visual Project, PCDP. [Google Scholar]

- Malkani, Mangharam. 1993. Sindhi Nasar Ji Mukhtasir Tareekh. Kandiaro: Roshini Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Manik. 1992. Rujj aen Parada. Roshni Publications, Kandiaro. Available online: https://books.sindhsalamat.com/book.php?book_id=638 (accessed on 17 June 2019).

- Manik. 1967. Haveli JaaRaaz. Hyderababd: Shuni Digest. [Google Scholar]

- Margaret, M. Swathy. 2012. Dalit Feminism. Roundtable India. Available online: https://roundtableindia.co.in (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Memon, Ghafoor. 2002. ‘Sindhi Adab jo Fikri Pasmanzar’. Karachi: Shah Latif Bhittai Chair. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, Chandrashekhar Dajiba. 2010. Buddhism and Dalit: Social Philosophy and Traditions. Delhi: Kalpas Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, Danish. 2007. Naseem Kharal Joon Kahariyoon’. Kandiaro: Roshini Publications, Available online: www.sindhsalamat.com (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Nicolas, F. Gier. 2006. From Mongols to Mughals: Religious Violence in India 9th-18th Centuries. Paper presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Metting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, USA, May 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ojha, Mangharam. 1966. Puranon Parkar, 6th ed. Hyderabad: Sindhi Adabi Board. [Google Scholar]

- Paleejo, Rasool Bux. 2016. ‘Sandi Zaat Hanjan’, 1st ed. Kandiaro: Roshni Publications. First published 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Paleejo, Rasool Bux. 2012. ‘Tanqeedi ain Takhleeki Adab’. Hyderabad: Center for Peace & Civil Society (CPCS). [Google Scholar]

- Qazi, Azad. 2015. Shaheed Rooplo Kolhi. Kandiaro: Roshni Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani, Ghulam. 2016. ‘Where Are the Pasmandas in Urdu Short Stories?’ in Forward Press. Available online: https://www.forwardpress.in (accessed on 16 June 2019).

- Raikes, Stanley Napier. 2009. Memoir on the Thurr and Parkur Districts of Sind: Selections from the Records of the Bomnbay Government. Lawndale: Sani Hussain Panhwar. First published 1856. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, Shalini. 2004. ‘Poisoned Bread’: Protest in Dalit Short Stories. Race & Class 45: 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, Ghulam Murtaza. 1952. Paigham-i-Latif. (the Online Translated Book). Available online: http://www.gmsyed.org/latif/book4-chap10.html (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- Sayed, Ghulam Murtaza. 1974. Sindh Ja Soorma. Naen Sindh Academy, Karachi. Available online: https://books.sindhsalamat.com/book.php?book_id=472 (accessed on 6 June 2019).

- Sayed, Ghulam Murtaza. 2013. Sindhu Desh. Lawndale: Sani Hussain Panhwar. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Noorulhuda. 2007a. Rin aen Rujj jo Itehas. Kandiaro: Roshini Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Noorulhuda. 2007b. Jalawatan. Kandiaro: Roshni Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Siraj. 2009. Sindhi Language. Hyderbad: Sindhi Langage Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Sripathi, Apoorva. 2017. Shit Has Hit the Fan with Raya Sarkar’s Post on Sexual Harassers in Indian Academia. But Will It Just Stop There? Available online: http://theladiesfinger.com (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Trivedi, Harish. 2017. The Urdu Premchand and the Hindi Premchand. Revista Brasileira de Literatura Comparada 19: 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, Shashi Bhushan. 2002. Representing the Underdogs: Dalits in the Literature of Premchand. Studies in History 18: 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, Shashi Bhushan. 2011. Premchand and the Moral Economy of Peasantry in Colonial North India. Modern Asian Studies 45: 1227–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velaskar, Padma. 2012. Education for Liberation: Ambedkar’s Thought and Dalit Women’s Perspectives. Contemporary Education Dialogue 9: 245–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajid, Muhammad. 2017. Forced Religious Conversion of Hindus in Sindh (Myth or Reality): A Case Study of Shahdadpur City. M.Phil. Thesis, International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan. [Google Scholar]

- Zelliot, Eleanor. 2011. Connected peoples: Pilgrimage in the structure of the Ambedkar movement. Contemporary Voice of Dalit 4: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Sindh is a province of Pakistan having about 47.89 million population (Source: Bureau of Census Pakistan), and is located at 25.8943° N, 68.5247° E coordinates on the world map. |

| 2 | Locally known as ‘Darawar’ (darāwaṛ) and Scheduled Castes, there live estimated 2–6 million Dalits. Kolhi, Bheel, and Meghwar are three major Dalit castes that live in Sindh (see Hussain 2019a). |

| 3 | Ashrafia class, i.e., Sayeds or the descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, and the castes claiming to be of Arab and Central Asian descent (see Hussain 2019a; Ahmad 2003; Kazuo 2004; Buehler 2012). |

| 4 | The bulk of the Sindhi literature is published in the form of books, magazines, and newspapers. To have an idea of the literature being produced in Sindhi language, see the following online libraries and Publishing houses: Sindhi Salamat. URL: https://books.sindhsalamat.com/ (accessed on 6 June 2019). Sindhi Adabi Borad. URL: http://www.sindhiadabiboard.org/Index.html (accessed on 6 June 2019). Sindhi Language Authority. URL: http://www.library.sindhila.org/home (accessed on 6 June 2019). Roshini Publications.URL: https://www.roshnipublication.com/. Sindhika Academy. URL: http://www.sindhica.net/English.htm (accessed on 6 June 2019). |

| 5 | Dalit worldview and their fundamental conceptions of self and society are essentially framed, for instance, in Gujarati or Parakari, Dhatki, or Rajasathani and Marvari or Kacthi languages. Therefore, they cannot express their deepest emotions and experiences in Sindhi language which they have adopted as the medium of communication under the ‘hegemonic’ influence of Ashrafia-Savarna culture. |

| 6 | Ashrafia class, i.e., Sayeds or the descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, and the castes claiming to be of Arab and Central Asian descent (see Hussain 2019a; Ahmad 2003; Kazuo 2004). |

| 7 | Amar Jaleel received the Kamal-i-Fun award, which is the highest award in Pakistan in the field of literature. Apart from that he also received Pride of Performance (Pakistan) and Akhil Bharat Sindhi Sahat Sabha National Award of India. |

| 8 | Karoonjhar is an isolated mountain about 7 km in length at the center of Parkar, the hiding place for the rebels during the British occupation of Tharparkar. |

| 9 | Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical guidelines recommended by the Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. The permission was sought, where required, from the concerned persons to reproduce any picture, graph, table, or piece of information. |

| 10 | To have an idea of how local Dalit activists in Sindh connect themselves with the Dalits and Amedkarites in India or elsewhere and problematize politics, culture, society and the literature, read the literature on Dalits in Sindhi written by local Ambedkarites made available by me on Mendely, the online database (see Bheel 2017; Hussain 2019c, 2019d, 2019e). |

| 11 | To have a comprehensive understanding of what I mean by Ambedkarian or Dalitbahujan perspective, read paper draft on ‘Mainstreaming Dalitbahujan perspective in Pakistan’ (2017). doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.23455.87200, URL: https://www.researchgate.net. |

| 12 | Noorul Huda Shah is one of the most celebrated Sindhi short story writer, Pakistani playwright and former caretaker provincial minister of Sindh Government in 2013. See: https://www.dawn.com/news/799025 (accessed on 6 June 2019). To have an idea of Noorul Huda Shah’s literary-political approach read her statements related to the literary production during General Zia’s regime, the period during which she wrote several drama serials for state-sponsored TV channel PTV. Further read in DAWN, URL: https://images.dawn.com/news/1178036 (accessed on 7 June 2019). |

| 13 | See Haveli JaaRaaz, (Manik 1967), first published in Sindhi digest ‘Shuni’. |

| 14 | Manik’s wife, however, maintains that Manik died of heart attack. Some of Manik’s close friends argue that although Manik was bitterly criticized for his writings, particular for his purportedly ‘sexually explicit’ depiction of patriarchal social reality and Sayedism, his circumstance of death has not much to do with it. |

| 15 | Source: ‘Naseem Kharal Joon Kahariyoon’ (2007), a compilation of short stories in Sindhi language by Danish Nawaz. Roshini Publications, Kandiaro. URL: www.sindhsalamat.com. This story was written in the 1960s by Naseem Kharal, the renowned upper caste landlord (wadero), and one of the leading Sindhi progressive writers of the 1960s and 1970s. |

| 16 | |

| 17 | Unlike her writings on Indian society and culture, which are quite critical of casteism and Dalit oppression (see for instance, her article on ‘Short Story in Gujarati Dalit Literature’ (Kothari 2001)). In it Kothari frames the society of Sindh primarily from Sindhi Savarna-Ashrafia lens. See also her blog post ‘Of Men, Women, Caste and Cinema’ at https://kafila.online, in which she assuming the feminist standpoint problematizes the misogyny of the producer while criticizing the deliberate absence of caste in Hindu cinema and the pretension ‘that the upper-caste characters are casteless.’ |

| 18 | Listen her lecture online, 18 | Prof. Rita Kothari | Sufism in Sindh | 18 April, (28 Aug 2017) published by IIT Gandhinagar. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J0sg_F6bZW0 (accessed on 8 September 2019). |

| 19 | See online blog written by Sufi Ghulam Hussain (me) on 9 December 2017 titled Why Dalits in Pakistan are reluctant to convert to Islam en masse! URL: http://roundtableindia.co.in/ (accessed on 19 March 2019). |

| 20 | The book by Heman Das Chandani titled Humerche Hoongar (Sindhi) was published in 2017. |

| 21 | The cry against forced conversions in Pakistan raised by the Savarna-Ashrafia Sindhi nationalists and the Christian elite in July 2019 made to the Congress of the United States. See: The Pioneer (21 July 201910 US Congressmen ask Trump to raise issue of Sindh with Pak PM Imran. URL: https://www.dailypioneer.com (accessed on 9 June 2019). See also India Today (22 July 2019) URL: https://www.indiatoday.in (accessed on 9 June 2019). |

| 22 | The reinvigorated literary assertion of Sindhi nationalists during the 1950s that reframed the narrative of Marvi was also noticed by Levesque and Bui (2014) in their cinematographic study of first Sindhi movie ‘Umar-Marvi’ made in 1956. They argued that the movie ‘contributed to the construction of a modern national imaginary for Sindhis in post-Partition Pakistan’ (see Levesque and Bui 2014, pp. 119–21). |

| 23 | Karoonjhar is an isolated mountain about 7 km in length at the center of Parkar, the hiding place for the rebels during the British occupation of Tharparkar. |

| 24 | Trywhitt was a British appointed captain and administrator at Parkar and was assigned the task to subdue Sodha Thakurs. |

| 25 | During the conversational interviews, Dalit activists were told that Satram Das of Atran Mori claimed that Rooplo is his grandfather. Comrade Bhagat Padhmon Kolhi of Sindhin-jo-wāndyo filed a case to get 50 acres of land of Parkar based on his claim that he was grandson of Rooplo. Veerji Kolhi (advisor to minister) and Krishna Kolhi (senator) claimed to have descended from Rooplo Kolhi. Lately, a team of local progressive-minded researchers led by Mir Hasan Arisar, Tahir Mari, Nawaz Kumbhar, Muhib Bheel, Sadam Dars and Ranshal Das attempted to locate the true ancestors of Rooplo Kolhi. According to their findings, Rooplo had a son called ‘Harkho’, and that Kheto Mal and Gulab Rai were the true grand-grandsons of ‘Shaheed Rooplo’. |

| 26 | Source: Daily Ibrat (Sindhi newspaper, Dated, 28th August, 2017. URL: http://www.dailyibrat.com/beta/pages/jpp_28082017015347.jpg (accessed on 8 July 2019). |

| 27 | Source: Sindh Express (daily), Monday, August, 28, 2017. URL: http://sindhexpress.com.pk/epaper/PoPupwindow.aspx?newsID=130546486&Issue=NP_HYD&Date=20170828 (accessed 8 on July 2019). |

| 28 | Source: Daily Sobh (Sindhi newspaper), Dated, 28th August, 2017. URL: http://www.dailysobh.com/beta/epaper/news/news.php?news_id=236 (accessed on 8 July 2019). |

| 29 | Some historiographers depict Dahar as an unpopular Brahmin king that ruled over Buddhist majority, and Chach, Dahar’s father is believed to be the usurper of Buddhist Rai Dynasty (see Nicolas 2006; Naik 2010, p. 32.) |

| 30 | The Battle of Bhima Koregaon Documentary Film Official Release | Director—Somnath Waghamare, Published by Roundtable India on 20 Aug 2017, Direction and Camera—Somnath Waghmare, Editor -Deepu (Pradeep K P), URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDw43hJf_IY&feature=share (accessed on 8 July 2019). |

| 31 | Holi Garho is small village in Pithapur which is union council of Nangarparkar. Dedhvero and Kabri are also villages of Nangarparkar that were dominated by the Thakur (Savarna) and Khosa (Baloh Ashrafia) caste groups. |

| 32 | Transhumance has been a common migratory practice among Parkaris, who used to migrate from Parkar to the plains of Indus (locally known as ‘barrage area’). Before Partition of the Sub-continent and the sealing of borders, they used to migrate to Kutch and Malwa in Maharshtra (see Mal 2000). |

| 33 | To read online some notable short stories of Premchand, see: URL: https://www.rekhta.org/stories/eidgah-premchand-stories?lang=ur (accessed on 6 June 2019). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hussain, G. Appropriation of Caste Spaces in Pakistan: The Theo-Politics of Short Stories in Sindhi Progressive Literature. Religions 2019, 10, 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10110627

Hussain G. Appropriation of Caste Spaces in Pakistan: The Theo-Politics of Short Stories in Sindhi Progressive Literature. Religions. 2019; 10(11):627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10110627

Chicago/Turabian StyleHussain, Ghulam. 2019. "Appropriation of Caste Spaces in Pakistan: The Theo-Politics of Short Stories in Sindhi Progressive Literature" Religions 10, no. 11: 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10110627

APA StyleHussain, G. (2019). Appropriation of Caste Spaces in Pakistan: The Theo-Politics of Short Stories in Sindhi Progressive Literature. Religions, 10(11), 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10110627