Different Countries, Common Support for Climate Change Mitigation: The Case of Germany and Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Climate Policy in European Union (EU)

1.3. Socioeconomic Background and Climate Policy in Germany and Poland

1.4. Factors Influencing Public Support for CC Mitigation

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Measurement of Support for CC Mitigation Policies

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Research Design

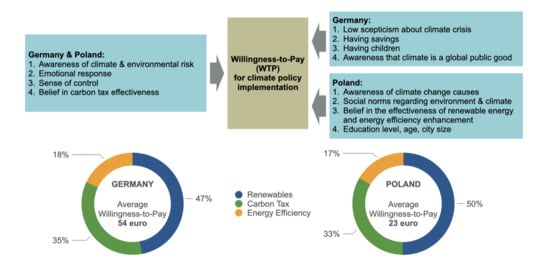

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Description of a current climate situation

- 2.

- Description of CC mitigation policies in the EU

- 3.

- Support for CC mitigation

- (a)

- Development of renewable energy sources.

- (b)

- Introduction of a carbon tax.

- (c)

- Improving energy efficiency.

References

- Poortinga, W.; Corner, A.J.; Arnold, A.; Böhm, G.; Mays, C. European Perceptions of Climate Change (EPCC): Topline Findings of a Survey Conducted in Four European Countries in 2016; Cardiff University: Cardiff, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Matczak, P. Climate change regional review: Poland. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2012, 3, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capstick, S.; Whitmarsh, L.; Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N.; Upham, P. International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century: International trends in public perceptions of climate change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2015, 6, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyselá, E.; Ščasný, M.; Zvěřinová, I. Attitudes toward climate change mitigation policies: A review of measures and a construct of policy attitudes. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 878–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S. Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: A cross-European analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 55, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Climate Action Going climate-neutral by 2050. In A Strategic Long-Term Vision for a Prosperous, Modern, Competitive and Climate-Neutral EU Economy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Delbeke, J.; Vis, P. (Eds.) EU Climate Policy Explained; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781317338123. [Google Scholar]

- Droege, S.; Fischer, C. Pricing Carbon at the Border: Key Questions for the EU. ifo DICE Rep. 2020, 18, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- World Population Prospects—Population Division—United Nations. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Mehling, M. Germany’s Ecological Tax Reform: A Retrospective. In Environmental Sustainability in Transatlantic Perspective: A Multidisciplinary Approach; Achilles, M., Elzey, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2013; pp. 91–103. ISBN 9781137334480. [Google Scholar]

- Radtke, J.; Kersting, N. (Eds.) Energiewende: Politikwissenschaftliche Perspektiven; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9783658215606. [Google Scholar]

- Energiewende im Überblick. Available online: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/energiewende/energiewende-im-ueberblick-229564 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- International Energy Agency—Germany. Available online: https://www.iea.org/countries/germany (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Murray, L. The need to rethink German Nuclear Power. Electr. J. 2019, 32, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwała, W.; Wyrwa, A.; Olkuski, T. Trends in coal use—Global, EU and Poland. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; Volume 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoczkowski, T.; Bielecki, S.; Węglarz, A.; Włodarczak, M.; Gutowski, P. Impact assessment of climate policy on Poland’s power sector. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2018, 23, 1303–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cianciara, A.K. Contestation of EU Climate Policy in Poland: Civil Society and Politics of National Interest. Prakseologia 2017, 159, 237–264. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Linden, S. The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Harris, E.A.; Bain, P.G.; Fielding, K.S. Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunlap, R.E. Climate Change Skepticism and Denial: An Introduction. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A.A.; Maibach, E.W. Climategate, public opinion, and the loss of trust. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 818–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norgaard, K.M. “We Don’t Really Want to Know”: Environmental Justice and Socially Organized Denial of Global Warming in Norway. Organ. Environ. 2006, 19, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgaard, K.M. “People want to protect themselves a little bit”: Emotions, denial, and social movement nonparticipation. Sociol. Inq. 2006, 76, 372–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castán Broto, V.; Bulkeley, H. A survey of urban climate change experiments in 100 cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mead, E.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Rimal, R.N.; Flora, J.A.; Maibach, E.W.; Leiserowitz, A. Information Seeking about Global Climate Change among Adolescents: The Role of Risk Perceptions, Efficacy Beliefs and Parental Influences. Atl. J. Commun. 2012, 20, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeelenberg, M.; Nelissen, R.M.A.; Breugelmans, S.M.; Pieters, R. On emotion specificity in decision making: Why feeling is for doing. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2008, 3, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P. An argument for basic emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and adaptation. In Handbook of Personality; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, G. Don’t Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change; Bloomsbury USA: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781632861023. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Ecker, U.K.H.; Seifert, C.M.; Schwarz, N.; Cook, J. Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2012, 13, 106–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Ecker, U.; Lewandowsky, S. Misinformation and how to correct it. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource; Wiley Online Libray: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J.D. Risk communication on climate: Mental models and mass balance. Science 2008, 322, 532–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Malka, A.; Krosnick, J.A.; Langer, G. The association of knowledge with concern about global warming: Trusted information sources shape public thinking. Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; Maibach, E.W.; Zhao, X.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Leiserowitz, A. Support for climate policy and societal action are linked to perceptions about scientific agreement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2011, 1, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krosnick, J.A.; Holbrook, A.L.; Lowe, L.; Visser, P.S. The Origins and Consequences of democratic citizens’ Policy Agendas: A Study of Popular Concern about Global Warming. Clim. Chang. 2006, 77, 7–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons: The population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension in morality. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ansari, S.; Wijen, F.; Gray, B. Constructing a Climate Change Logic: An Institutional Perspective on the “Tragedy of the Commons”. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 1014–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunlap, R.E. Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, E.; Axsen, J.; Jaccard, M. Exploring Citizen Support for Different Types of Climate Policy. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 137, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahran, S.; Brody, S.D.; Grover, H.; Vedlitz, A. Climate Change Vulnerability and Policy Support. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 771–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Dan, A.; Shwom, R. Support for Climate Change Policy: Social Psychological and Social Structural Influences. Rural Sociol. 2007, 72, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Connor, R.E.; Bord, R.J.; Yarnal, B.; Wiefek, N. Who Wants to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions? Soc. Sci. Q. 2002, 83, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Bennett, J.; Ward, M.B. Climate Change Scepticism and Public Support for Mitigation: Evidence from an Australian Choice Experiment; Monash University, Department of Economics: Clayton, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, A.J.; Whitmarsh, L.E.; Xenias, D. Uncertainty, scepticism and attitudes towards climate change: Biased assimilation and attitude polarisation. Clim. Chang. 2012, 114, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.U.; Stern, P.C. Public understanding of climate change in the United States. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Nolan, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- March, J.G. Primer on Decision Making: How Decisions Happen; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ščasný, M.; Zvěřinová, I.; Czajkowski, M.; Kyselá, E.; Zagórska, K. Public acceptability of climate change mitigation policies: A discrete choice experiment. Clim. Policy 2017, 17, S111–S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotchen, M.J.; Boyle, K.J.; Leiserowitz, A.A. Willingness-to-pay and policy-instrument choice for climate-change policy in the United States. Energy Policy 2013, 55, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehleke, R. The role of question format for the support for national climate change mitigation policies in Germany and the determinants of WTP. Energy Econ. 2016, 55, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, F.; Kataria, M.; Krupnick, A.; Lampi, E.; Löfgren, Å.; Qin, P.; Chung, S.; Sterner, T. Paying for Mitigation: A Multiple Country Study; University of Gothenburg, Department of Economics: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, T.A. Individual option prices for climate change mitigation. J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Layton, D.F.; Brown, G. Heterogeneous Preferences Regarding Global Climate Change. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2000, 82, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.; Czajkowski, M. The Discrete Choice Experiment Approach to Environmental Contingent Valuation. In Handbook of Choice Modelling; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arrow, K.; Solow, R.; Portney, P.R.; Leamer, E.E.; Radner, R.; Schuman, H. Report of the NOAA panel on contingent valuation. Fed. Regist. 1993, 58, 4601–4614. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam, L. The contingent valuation method: A review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 89–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocera, S.; Telser, H.; Bonato, D. The Contingent Valuation Method in Health Care: An Economic Evaluation of Alzheimer’s Disease; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781441991331. [Google Scholar]

- Vossler, C.A.; Doyon, M.; Rondeau, D. Truth in Consequentiality: Theory and Field Evidence on Discrete Choice Experiments. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2012, 4, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Czajkowski, M.; Vossler, C.A.; Budziński, W.; Wiśniewska, A.; Zawojska, E. Addressing empirical challenges related to the incentive compatibility of stated preferences methods. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2017, 142, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: Dimensions, determinants and change over time. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, S. Cognitive Reflection and Decision Making. J. Econ. Perspect. 2005, 19, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brañas-Garza, P.; Kujal, P.; Lenkei, B. Cognitive reflection test: Whom, how, when. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2019, 82, 101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernauer, T.; Gampfer, R. How robust is public support for unilateral climate policy? Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 54, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannlund, R.; Persson, L. To tax, or not to tax: Preferences for climate policy attributes. Clim. Policy 2012, 12, 704–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallbekken, S.; Sælen, H. Public acceptance for environmental taxes: Self-interest, environmental and distributional concerns. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 2966–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.E. Environment and development challenges: The imperative of a carbon fee and dividend. In The Oxford Handbook of the Macroeconomics of Global Warming; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mackie, A.; Haščič, I. The Distributional Aspects of Environmental Quality and Environmental Policies: Opportunities for Individuals and Households; OECD Green Growth Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Germany Census | German Sample | Poland Census | Polish Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 50.7% | 48.7% | 49.8% | 42.6% |

| Female | 49.3% | 51.3% | 50.2% | 57.4% |

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 | 11.9% | 8.8% | 11.4% | 11.8% |

| 25–29 | 10.1% | 23.7% | 10.3% | 16.7% |

| 30–39 | 19.9% | 29.4% | 24.7% | 31.6% |

| 40–49 | 20.5% | 34.8% | 21.7% | 30.1% |

| 50–59 | 25.5% | 3.3% | 18.9% | 9.7% |

| 60–65 | 12.1% | 0% | 13.1% | 0% |

| City size | ||||

| Village | 23.7% | 15.2% | 40.4% | 35.0% |

| Up to 50 k inhabitants | 35.6% | 26.4% | 24.1% | 20.2% |

| 50–200 k inhabitants | 15.5% | 22.4% | 16.0% | 19.7% |

| 200–500 k inhabitants | 8.5% | 29.7% | 8.3% | 11.2% |

| Above 500 k inhabitants | 16.8% | 6.4% | 11.2% | 13.8% |

| Education | ||||

| Primary and lower secondary education | 37.6% | Not included | 37.6% | Not included |

| Upper secondary and post-secondary | 23.3% | 37.6% | 35.9% | 35.2% |

| Tertiary education | 39.1% | 62.4% | 26.5% | 64.7% |

| Variable | Question/Description | Hypothesized Effect on CC Mitigation Support |

|---|---|---|

| CC as a global risk | Q: Which from the following list of global problems would you include among those to be tackled first? Please select a maximum of five ->chosen item “Anthropogenic climate change” | Positive |

| CC_Impact_now CC_Impact_20 CC_Impact_50 | Q: What is the impact of climate change on the life of an average German/Pole at the moment/in 20 years/in 50 years? ->answer on a five-point scale | Positive |

| Maximum temperature increase | Q: In your opinion, what maximum increase in the average temperature on Earth, compared to the period before the industrial revolution (1850–1900), should be considered safe: ->range from +1.0 °C to +5.1 °C and more | Negative |

| Denial | Nine statements evaluated on a five-point scale estimating level of denial on four dimensions: emotions, norms, selective attention and perspectival selectivity | Negative |

| Public good | Evaluation of the awareness that the climate is a global public (common) good | Positive |

| Skepticism | Result on a skepticism scale, based on 17 statements evaluated on a five-point scale | Negative |

| NEP scale | Result on a full NEP scale (15 statements) | Positive |

| CC awareness | Q: How do you assess your level of awareness of global warming (otherwise known as “climate change”)? | Positive |

| IPCC awareness | Q: How familiar are you with the IPCC? | Positive |

| CC causes | Evaluation of objective knowledge of the causes of climate change based on the answers to six questions | Positive |

| CC impacts | Evaluation of objective knowledge of the effects of climate change based on the answers to eight questions | Positive |

| Social norms | Four statements evaluating norms related to CC mitigation | Positive |

| Control | Evaluation of the feeling of control over the climate situation, based on the answers to six questions | Positive |

| Policy effectiveness | Perceived effectiveness of evaluated policies (renewable energy, carbon tax, energy efficiency) | Positive |

| Cognitive Reflection Test | Person’s cognitive ability, measured with the Cognitive Reflection Test | Positive |

| Sociodemographic variables | Gender, age, education, city size, financial situation, savings, faith in God, country |

| Dependent Variable: log(WTP) | German Sample (n = 970) R2 adj. = 0.288; Durbin–Watson = 1.930 | Polish Sample (n = 999) R2 adj. = 0.284; Durbin–Watson = 2.114 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (std) | SE | p | Beta (std) | SE | p | |

| Constant | 0.880 | 0.000 * | 0.891 | 0.000 * | ||

| CC as a global risk | 0.064 | 0.093 | 0.042 * | 0.121 | 0.095 | 0.000 * |

| IPCC awareness | 0.104 | 0.045 | 0.002 * | 0.088 | 0.055 | 0.007 * |

| Emotions (denial scale) | 0.098 | 0.072 | 0.001 * | 0.093 | 0.079 | 0.002 * |

| Control | 0.132 | 0.059 | 0.000 * | 0.156 | 0.093 | 0.000 * |

| Effectiveness of carbon tax | 0.146 | 0.044 | 0.000 * | 0.153 | 0.042 | 0.000 * |

| Causes | 0.01 | 0.109 | 0.766 | 0.095 | 0.108 | 0.002 * |

| Education | −0.009 | 0.061 | 0.748 | −0.071 | 0.061 | 0.013 * |

| CC awareness | −0.027 | 0.024 | 0.409 | −0.069 | 0.027 | 0.035 * |

| Social norms | 0.03 | 0.072 | 0.384 | 0.120 | 0.084 | 0.001 * |

| Financial situation | 0.041 | 0.065 | 0.195 | 0.063 | 0.075 | 0.044 * |

| City size | 0.037 | 0.021 | 0.192 | −0.065 | 0.02 | 0.023 * |

| Perceived effectiveness of energy efficiency | 0.059 | 0.056 | 0.102 | 0.095 | 0.058 | 0.006 * |

| Perceived effectiveness of renewables | 0.063 | 0.053 | 0.084 | −0.108 | 0.056 | 0.002 * |

| Age | −0.057 | 0.005 | 0.067 | −0.070 | 0.005 | 0.027 * |

| Public good | 0.063 | 0.072 | 0.030 * | 0.026 | 0.073 | 0.352 |

| Skepticism | −0.144 | 0.090 | 0.003 * | −0.064 | 0.098 | 0.158 |

| Savings | 0.094 | 0.098 | 0.003 * | 0.055 | 0.099 | 0.079 |

| Children | 0.065 | 0.046 | 0.034 * | 0.054 | 0.045 | 0.07 |

| Impacts | 0.009 | 0.066 | 0.808 | −0.054 | 0.072 | 0.101 |

| NEP scale | 0.022 | 0.106 | 0.580 | 0.049 | 0.124 | 0.218 |

| Perspectival selectivity (denial scale) | −0.024 | 0.050 | 0.447 | 0.043 | 0.056 | 0.159 |

| CC impact in 20 years | −0.019 | 0.076 | 0.683 | −0.042 | 0.086 | 0.432 |

| Gender | 0.023 | 0.086 | 0.423 | 0.038 | 0.098 | 0.219 |

| CC impact now | −0.020 | 0.043 | 0.537 | 0.031 | 0.045 | 0.368 |

| CC impact in 50 years | 0.054 | 0.075 | 0.244 | 0.080 | 0.076 | 0.092 |

| Faith in God | 0.012 | 0.031 | 0.683 | 0.012 | 0.038 | 0.684 |

| Maximum temperature | 0.021 | 0.025 | 0.48 | 0.011 | 0.02 | 0.687 |

| Cognitive Reflection Test | −0.014 | 0.039 | 0.635 | −0.003 | 0.046 | 0.913 |

| Norms (denial scale) | −0.045 | 0.058 | 0.131 | −0.014 | 0.067 | 0.638 |

| Selective attention (denial scale) | −0.047 | 0.053 | 0.165 | 0.002 | 0.058 | 0.962 |

| Rotated Component Matrix | German Sample (n = 970) | Polish Sample (n = 999) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| % of Variance: | 18.9% | 16.4% | 11.5% | 10.2% | 9.0% | 17.4% | 17.3% | 12.3% | 9.4% | 8.6% |

| Impacts | −0.813 | −0.663 | ||||||||

| Causes | −0.776 | −0.683 | ||||||||

| NEP scale | −0.727 | −0.618 | ||||||||

| Skepticism | 0.620 | −0.540 | 0.564 | −0.563 | ||||||

| Selective attention (denial scale) | −0.683 | −0.615 | ||||||||

| Norms (denial scale) | −0.669 | |||||||||

| Social norms | 0.626 | 0.735 | ||||||||

| Control | 0.619 | 0.812 | ||||||||

| CC awareness | 0.853 | 0.840 | ||||||||

| IPCC awareness | 0.838 | 0.837 | ||||||||

| Perspectival selectivity (denial scale) | −0.774 | 0.556 | ||||||||

| Public good | −0.627 | −0.761 | ||||||||

| Emotions (denial scale) | 0.923 | 0.940 | ||||||||

| Dependent Variable: log(WTP) | German Sample (n = 970) R2 adj. = 0.221; Durbin–Watson = 1.888 | Polish Sample (n = 999) R2 adj. = 0.195; Durbin–Watson = 2.059 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (std) | SE | p | Beta (std) | SE | p | |

| (Constant) | 0.42 | 0.000 * | ||||

| Component 1 (Germany) | −0.160 | 0.42 | 0.000 * | |||

| Component 2 (Germany) | 0.332 | 0.42 | 0.000 * | |||

| Component 3 (Germany) | −0.118 | 0.42 | 0.000 * | |||

| Component 4 (Germany) | −0.092 | 0.42 | 0.001 * | |||

| Component 5 (Germany) | −0.259 | 0.42 | 0.000 * | |||

| (Constant) | 0.45 | 0.000 * | ||||

| Component 1 (Poland) | −0.123 | 0.45 | 0.000 * | |||

| Component 2 (Poland) | −0.361 | 0.45 | 0.000 * | |||

| Component 3 (Poland) | 0.064 | 0.45 | 0.025 * | |||

| Component 4 (Poland) | −0.037 | 0.45 | 0.195 | |||

| Component 5 (Poland) | −0.221 | 0.45 | 0.000 * | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bohdanowicz, Z. Different Countries, Common Support for Climate Change Mitigation: The Case of Germany and Poland. Climate 2021, 9, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli9020027

Bohdanowicz Z. Different Countries, Common Support for Climate Change Mitigation: The Case of Germany and Poland. Climate. 2021; 9(2):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli9020027

Chicago/Turabian StyleBohdanowicz, Zbigniew. 2021. "Different Countries, Common Support for Climate Change Mitigation: The Case of Germany and Poland" Climate 9, no. 2: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli9020027

APA StyleBohdanowicz, Z. (2021). Different Countries, Common Support for Climate Change Mitigation: The Case of Germany and Poland. Climate, 9(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli9020027