Biomedical Applications of Plant Extract-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Synthesis of AgNPs

2.1. Green Synthesis of MNPs

2.2. AgNPs Synthesis Using Microbes

2.3. AgNPs Synthesis Using Plant Extracts

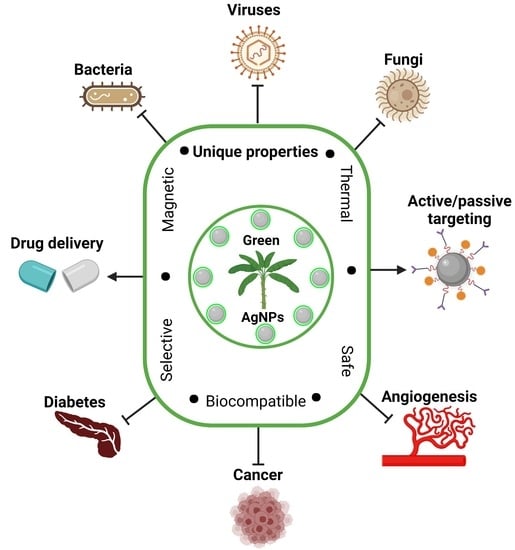

3. Biomedical Applications of Biogenic AgNPs

3.1. Anti-Microbial Applications of Biogenic AgNPs

3.1.1. Anti-Bacterial Activity

3.1.2. Anti-Fungal Activity

3.1.3. Anti-Viral Activity

3.2. Anti-Angiogenesis Activity

3.3. Anti-Cancer Activity

3.4. Anti-Diabetic Activity

3.5. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

3.6. AgNPs as Drug Delivery Agents

4. Perspectives and Concerns for Clinical Application of AgNPs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Moabelo, K.L.; Fadaka, A.O.; Meyer, S.; Onani, M.O.; Madiehe, A.M.; Meyer, M. Multifunctional Gold Nanoparticles for Improved Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications: A Review. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, S.; Singh, H.; Trivedi, R.; Soni, V. Biogenic Synthesis of AgNPs Employing Terminalia Arjuna Leaf Extract and Its Efficacy towards Catalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, P.D.; Banas, D.; Durai, R.D.; Kabanov, D.; Hosnedlova, B.; Kepinska, M.; Fernandez, C.; Ruttkay-Nedecky, B.; Nguyen, H.V.; Farid, A.; et al. Silver Nanomaterials for Wound Dressing Applications. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Jun, B.H. Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Application for Nanomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Calderón-Jiménez, B.; Johnson, M.E.; Montoro Bustos, A.R.; Murphy, K.E.; Winchester, M.R.; Baudrit, J.R.V. Silver Nanoparticles: Technological Advances, Societal Impacts, and Metrological Challenges. Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beyene, H.D.; Werkneh, A.A.; Bezabh, H.K.; Ambaye, T.G. Synthesis Paradigm and Applications of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs), a Review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2017, 13, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamkhande, P.G.; Ghule, N.W.; Bamer, A.H.; Kalaskar, M.G. Metal Nanoparticles Synthesis: An Overview on Methods of Preparation, Advantages and Disadvantages, and Applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdușel, A.C.; Gherasim, O.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Mogoantă, L.; Ficai, A.; Andronescu, E. Biomedical Applications of Silver Nanoparticles: An up-to-Date Overview. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haider, A.; Kang, I.K. Preparation of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Industrial and Biomedical Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 2015, 165257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nqakala, Z.B.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Fadaka, A.O.; Meyer, M.; Onani, M.O.; Madiehe, A.M. Advances in Nanotechnology towards Development of Silver Nanoparticle-Based Wound-Healing Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Han, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S. On the Developmental Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles. Mater. Des. 2021, 203, 109611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levard, C.; Hotze, E.M.; Lowry, G.V.; Brown, G.E. Environmental Transformations of Silver Nanoparticles: Impact on Stability and Toxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 6900–6914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortella, G.R.; Rubilar, O.; Durán, N.; Diez, M.C.; Martínez, M.; Parada, J.; Seabra, A.B. Silver Nanoparticles: Toxicity in Model Organisms as an Overview of Its Hazard for Human Health and the Environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 390, 121974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboyewa, J.A.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Meyer, M.; Oguntibeju, O.O. Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles Using Some Selected Medicinal Plants from Southern Africa and Their Biological Applications. Plants 2021, 10, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chand, K.; Cao, D.; Eldin Fouad, D.; Hussain Shah, A.; Qadeer Dayo, A.; Zhu, K.; Nazim Lakhan, M.; Mehdi, G.; Dong, S. Green Synthesis, Characterization and Photocatalytic Application of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Various Plant Extracts. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 8248–8261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Fadaka, A.O.; Meyer, M.; Madiehe, A.M.; du Preez, M.G. The Antimicrobial Activity of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized from Extracts of Red and Green European Pear Cultivars. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2021, 49, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyavambiza, C.; Elbagory, A.M.; Madiehe, A.M.; Meyer, M.; Meyer, S. The Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesised from Cotyledon Orbiculata Aqueous Extract. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majoumouo, M.S.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Tincho, M.B.; Mbekou, M.; Boyom, F.F.; Meyer, M. Enhanced Anti-Bacterial Activity of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized from Terminalia Mantaly Extracts. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 9031–9046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karmous, I.; Pandey, A.; Haj, K.; Ben; Chaoui, A. Efficiency of the Green Synthesized Nanoparticles as New Tools in Cancer Therapy: Insights on Plant-Based Bioengineered Nanoparticles, Biophysical Properties, and Anticancer Roles. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 196, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Jung, H.C.; Baek, Y.J.; Kim, B.Y.; Lee, M.W.; Kim, H.D.; Kim, S.W. Antibacterial Activity of Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Areca Catechu Extract against Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, P.; Nisha, K.M.J.; Vanitha, A.; Kiruthika, M.L.; Sindhu, P.; Elesawy, B.H.; Brindhadevi, K.; Kalimuthu, K. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Wild and Tissue Cultured Ceropegia Juncea Plants and Its Antibacterial, Anti-Angiogenesis and Cytotoxic Activities. Appl. Nanosci. 2021, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitimu, S.R.; Kirira, P.; Abdille, A.A.; Sokei, J.; Ochwang’i, D.; Mwitari, P.; Makanya, A.; Maina, N.; Kitimu, S.R.; Kirira, P.; et al. Anti-Angiogenic and Anti-Metastatic Effects of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Azadirachta Indica. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratan, Z.A.; Haidere, M.F.; Nurunnabi, M.; Shahriar, S.M.; Ahammad, A.J.S.; Shim, Y.Y.; Reaney, M.J.T.; Cho, J.Y. Green Chemistry Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Potential Anticancer Effects. Cancers 2020, 12, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sati, S.C.; Kour, G.; Bartwal, A.S.; Sati, M.D. Biosynthesis of Metal Nanoparticles from Leaves of Ficus Palmata and Evaluation of Their Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Diabetic Activities. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 3019–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saratale, R.G.; Saratale, G.D.; Ahn, S.; Shin, H.S. Grape Pomace Extracted Tannin for Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: Assessment of Their Antidiabetic, Antioxidant Potential and Antimicrobial Activity. Polymer 2021, 13, 4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdhouse, M.J.; Lalitha, P. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Its Applications. J. Nanotechnol. 2015, 2015, 829526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, P.; Ahn, S.; Kang, J.P.; Veronika, S.; Huo, Y.; Singh, H.; Chokkaligam, M.; El-Agamy Farh, M.; Aceituno, V.C.; Kim, Y.J.; et al. In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Spherical Silver Nanoparticles and Monodisperse Hexagonal Gold Nanoparticles by Fruit Extract of Prunus Serrulata: A Green Synthetic Approach. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 2022–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Natsuki, J. A Review of Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis Methods, Properties and Applications. Int. J. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2015, 4, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abbasi, B.H.; Nazir, M.; Muhammad, W.; Hashmi, S.S.; Abbasi, R.; Rahman, L.; Hano, C. A Comparative Evaluation of the Antiproliferative Activity against HepG2 Liver Carcinoma Cells of Plant-Derived Silver Nanoparticles from Basil Extracts with Contrasting Anthocyanin Contents. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hussain, I.; Singh, N.B.; Singh, A.; Singh, H.; Singh, S.C. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Its Potential Application. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, H.; Sood, D.; Chandra, I.; Tomar, V.; Dhawan, G.; Chandra, R. Role of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles in Cancer Nano-Medicine. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teimuri-mofrad, R.; Hadi, R.; Tahmasebi, B.; Farhoudian, S.; Mehravar, M.; Nasiri, R. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Plant Extract: Mini-Review. Nanochem. Res. 2017, 2, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi, B.; Bordbar, M.; Yeganeh-Faal, A.; Nasrollahzadeh, M. Green Synthesis of Ag Nanoparticles/Clinoptilolite Using Vaccinium Macrocarpon Fruit Extract and Its Excellent Catalytic Activity for Reduction of Organic Dyes. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 719, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballottin, D.; Fulaz, S.; Souza, M.L.; Corio, P.; Rodrigues, A.G.; Souza, A.O.; Gaspari, P.M.; Gomes, A.F.; Gozzo, F.; Tasic, L. Elucidating Protein Involvement in the Stabilization of the Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, P.; Li, N.; Astruc, D. State of the Art in Gold Nanoparticle Synthesis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 638–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageswari, A.; Subramanian, P.; Ravindran, V.; Yesodharan, S.; Bagavan, A.; Rahuman, A.A.; Karthikeyan, S.; Gothandam, K.M. Synthesis and Larvicidal Activity of Low-Temperature Stable Silver Nanoparticles from Psychrotolerant Pseudomonas Mandelii. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 5383–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, H.A.M.; El-Desouky, T.A. Green Synthesis of Nanosilver Particles by Aspergillus Terreus HA1N and Penicillium Expansum HA2N and Its Antifungal Activity against Mycotoxigenic Fungi. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dawadi, S.; Katuwal, S.; Gupta, A.; Lamichhane, U.; Thapa, R.; Jaisi, S.; Lamichhane, G.; Bhattarai, D.P.; Parajuli, N. Current Research on Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications. J. Nanomater. 2021, 2021, 6687290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, S.; Sardar, M.; Fatma, T. Screening of Cyanobacterial Extracts for Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 31, 1279–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomorodian, K.; Pourshahid, S.; Sadatsharifi, A.; Mehryar, P.; Pakshir, K.; Rahimi, M.J.; Arabi Monfared, A. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles by Aspergillus Species. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 5435397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahlawat, G.; Choudhury, A.R. A Review on the Biosynthesis of Metal and Metal Salt Nanoparticles by Microbes. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 12944–12967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamouda, R.A.; Hussein, M.H.; Abo-elmagd, R.A.; Bawazir, S.S. Synthesis and Biological Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles Derived from the Cyanobacterium Oscillatoria Limnetica. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aboyewa, J.A.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Meyer, M.; Oguntibeju, O.O. Gold Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Extracts of Cyclopia Intermedia, Commonly Known as Honeybush, Amplify the Cytotoxic Effects of Doxorubicin. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.; Sadaf, I.; Rafique, M.S.; Tahir, M.B. A Review on Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Applications. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 1272–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, S.A.; Preis, E.; Bakowsky, U.; Azzazy, H.M.E.S. Platinum Nanoparticles: Green Synthesis and Biomedical Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, A.A.; Raafat, D.; El-Gowelli, H.M.; El-Kamel, A.H. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Cranberry Powder Aqueous Extract: Characterization and Antimicrobial Properties. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 7207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srikar, S.K.; Giri, D.D.; Pal, D.B.; Mishra, P.K.; Upadhyay, S.N. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: A Review. Green Sustain. Chem. 2016, 6, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patel, V.; Berthold, D.; Puranik, P.; Gantar, M. Screening of Cyanobacteria and Microalgae for Their Ability to Synthesize Silver Nanoparticles with Antibacterial Activity. Biotechnol. Rep. 2015, 5, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fadaka, A.O.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Madiehe, A.M.; Meyer, M. Nanotechnology-Based Delivery Systems for Antimicrobial Peptides. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélteky, P.; Rónavári, A.; Igaz, N.; Szerencsés, B.; Tóth, I.Y.; Pfeiffer, I.; Kiricsi, M.; Kónya, Z. Silver Nanoparticles: Aggregation Behavior in Biorelevant Conditions and Its Impact on Biological Activity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailova, E.O. Silver Nanoparticles: Mechanism of Action and Probable Bio-Application. J. Funct. Biomater. 2020, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotcherlakota, R.; Das, S.; Patra, C.R. Therapeutic Applications of Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780081025796. [Google Scholar]

- Dakal, T.C.; Kumar, A.; Majumdar, R.S.; Yadav, V. Mechanistic Basis of Antimicrobial Actions of Silver Nanoparticles. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Forde, B.M.; Kidd, T.J.; Harris, P.N.A.; Schembri, M.A.; Beatson, S.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Walker, M.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00181-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, F.; Anywar, G.; Tang, H.; Chassagne, F.; Lyles, J.T.; Garbe, L.A.; Quave, C.L. Targeting ESKAPE Pathogens with Anti-Infective Medicinal Plants from the Greater Mpigi Region in Uganda. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsammarraie, F.K.; Wang, W.; Zhou, P.; Mustapha, A.; Lin, M. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Turmeric Extracts and Investigation of Their Antibacterial Activities. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 171, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, P.; Meyer, S.; Madiehe, A.; Meyer, M. Antibacterial Activity of Biogenic Silver and Gold Nanoparticles Synthesized from Salvia Africana-Lutea and Sutherlandia Frutescens. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 505607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi Lan Huong, V.; Nguyen, N.T. Green Synthesis, Characterization and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Using Sapindus Mukorossi Fruit Pericarp Extract. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 42, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsène, M.M.J.; Podoprigora, I.V.; Davares, A.K.L.; Razan, M.; Das, M.S.; Senyagin, A.N. Antibacterial Activity of Grapefruit Peel Extracts and Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Vet. World 2021, 14, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Hoque, S.M.; Hossain, K.F.B.; Siddique, M.A.B.; Uddin, M.K.; Rahman, M.M. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Ipomoea Aquatica Leaf Extract and Its Cytotoxicity and Antibacterial Activity Assay. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2020, 13, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aadil, K.R.; Pandey, N.; Mussatto, S.I.; Jha, H. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Acacia Lignin, Their Cytotoxicity, Catalytic, Metal Ion Sensing Capability and Antibacterial Activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, I.; Aftrid, Z.H.V.I. Characteristics and Antibacterial Activity of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Red Spinach (Amaranthus tricolor L.) Leaf Extract. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2019, 12, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, S.; Munir, S.; Zeb, N.; Ullah, A.; Khan, B.; Ali, J.; Bilal, M.; Omer, M.; Alamzeb, M.; Salman, S.M.; et al. Green Nanotechnology: A Review on Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles—An Ecofriendly Approach. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Savithramma, N.; Rao, M.; Rukmini, K.; Suvarnalatha-Devi, P. Antimicrobial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Using Medicinal Plants. Int.J. ChemTech Res. 2011, 3, 1394–1402. [Google Scholar]

- Ghojavand, S.; Madani, M.; Karimi, J. Green Synthesis, Characterization and Antifungal Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Using Stems and Flowers of Felty Germander. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 2987–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami-Teimoori, B.; Nikparast, Y.; Hojatianfar, M.; Akhlaghi, M.; Ghorbani, R.; Pourianfar, H.R. Characterisation and Antifungal Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Biologically Synthesised by Amaranthus Retroflexus Leaf Extract. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2017, 12, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, M.; Khan, A.U.; Bogdanchikova, N.; Garibo, D. Antibacterial and Antifungal Studies of Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles against Plant Parasitic Nematode Meloidogyne Incognita, Plant Pathogens Ralstonia Solanacearum and Fusarium Oxysporum. Molecules 2021, 26, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, A.; Naomi, R.; Utami, N.D.; Mohammad, A.W.; Mahmoudi, E.; Mustafa, N.; Fauzi, M.B. The Potential of Silver Nanoparticles for Antiviral and Antibacterial Applications: A Mechanism of Action. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, M.; Kon, K.; Ingle, A.; Duran, N.; Galdiero, S.; Galdiero, M. Broad-Spectrum Bioactivities of Silver Nanoparticles: The Emerging Trends and Future Prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 1951–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Munoz, R.; Lopez-Ribot, J. Nanotechnology as an Alternative to Reduce the Spread of COVID-19. Challenges 2020, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gusseme, B.; Sintubin, L.; Baert, L.; Thibo, E.; Hennebel, T.; Vermeulen, G.; Uyttendaele, M.; Verstraete, W.; Boon, N. Biogenic Silver for Disinfection of Water Contaminated with Viruses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Narasimha, G. Antiviral Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Fungal Strain Aspergillus Niger. Nano Sci. Nano Technol. Indian J. 2012, 6, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, H.H.; Ixtepan-Turrent, L.; Garza-Treviño, E.N.; Rodriguez-Padilla, C. PVP-Coated Silver Nanoparticles Block the Transmission of Cell-Free and Cell-Associated HIV-1 in Human Cervical Culture. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speshock, J.L.; Murdock, R.C.; Braydich-Stolle, L.K.; Schrand, A.M.; Hussain, S.M. Interaction of Silver Nanoparticles with Tacaribe Virus. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trefry, J.C.; Wooley, D.P. Silver Nanoparticles Inhibit Vaccinia Virus Infection by Preventing Viral Entry through a Macropinocytosis-Dependent Mechanism. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2013, 9, 1624–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Zaidi, N. us S.S.; Amraiz, D.; Afzal, F. In Vitro Antiviral Activity of Cinnamomum Cassia and Its Nanoparticles Against H7N3 Influenza A Virus. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 26, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Kaushik, S.; Pandit, P.; Dhull, D.; Yadav, J.P.; Kaushik, S. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Medicinal Plants and Evaluation of Their Antiviral Potential against Chikungunya Virus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggag, E.G.; Elshamy, A.M.; Rabeh, M.A.; Gabr, N.M.; Salem, M.; Youssif, K.A.; Samir, A.; Bin Muhsinah, A.; Alsayari, A.; Abdelmohsen, U.R. Antiviral Potential of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles of Lampranthus Coccineus and Malephora Lutea. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 6217–6229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saeed, B.A.; Lim, V.; Yusof, N.A.; Khor, K.Z.; Rahman, H.S.; Samad, N.A. Antiangiogenic Properties of Nanoparticles: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baharara, J.; Namvar, F.; Mousavi, M.; Ramezani, T.; Mohamad, R. Anti-Angiogenesis Effect of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Saliva Officinalis on Chick Chorioalantoic Membrane (CAM). Molecules 2014, 19, 13498–13508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goradel, N.H.; Ghiyami-Hour, F.; Jahangiri, S.; Negahdari, B.; Sahebkar, A.; Masoudifar, A.; Mirzaei, H. Nanoparticles as New Tools for Inhibition of Cancer Angiogenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 2902–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S. Recent Progress toward Antiangiogenesis Application of Nanomedicine in Cancer Therapy. Futur. Sci. OA 2018, 4, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dvorak, H.F. Vascular Permeability Factor/Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor: A Critical Cytokine in Tumor Angiogenesis and a Potential Target for Diagnosis and Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 4368–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, H.P.; Dixit, V.; Ferrara, N. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Induces Expression of the Antiapoptotic Proteins Bcl-2 and A1 in Vascular Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 13313–13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carmeliet, P. Angiogenesis in Life, Disease and Medicine. Nature 2005, 438, 932–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, J. What Is the Evidence That Tumors Are Angiogenesis Dependent? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990, 82, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jain, P.K.; Lee, K.S.; El-Sayed, I.H.; El-Sayed, M.A. Calculated Absorption and Scattering Properties of Gold Nanoparticles of Different Size, Shape, and Composition: Applications in Biological Imaging and Biomedicine. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 7238–7248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kong, D.H.; Kim, M.R.; Jang, J.H.; Na, H.J.; Lee, S. A Review of Anti-Angiogenic Targets for Monoclonal Antibody Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dragovich, T.; Laheru, D.; Dayyani, F.; Bolejack, V.; Smith, L.; Seng, J.; Burris, H.; Rosen, P.; Hidalgo, M.; Ritch, P.; et al. Phase II Trial of Vatalanib in Patients with Advanced or Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma after First-Line Gemcitabine Therapy (PCRT O4-001). Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014, 74, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Motzer, R.J.; Escudier, B.; Gannon, A.; Figlin, R.A. Sunitinib: Ten Years of Successful Clinical Use and Study in Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. Oncologist 2017, 22, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, G.; Wei, X.; Xu, X. Is the Era of Sorafenib over? A Review of the Literature. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835920927602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Hurwitz, H.I.; Sandler, A.B.; Miles, D.; Coleman, R.L.; Deurloo, R.; Chinot, O.L. Bevacizumab (Avastin®) in Cancer Treatment: A Review of 15 Years of Clinical Experience and Future Outlook. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 86, 102017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, B.T.; Raguraman, P.; Kosbar, T.R.; Fletcher, S.; Wilton, S.D.; Veedu, R.N. Antisense Oligonucleotides Targeting Angiogenic Factors as Potential Cancer Therapeutics. Mol. Ther.-Nucleic Acids 2019, 14, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walia, A.; Yang, J.F.; Huang, Y.H.; Rosenblatt, M.I.; Chang, J.H.; Azar, D.T. Endostatin’s Emerging Roles in Angiogenesis, Lymphangiogenesis, Disease, and Clinical Applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Gen. Subj. 2015, 1850, 2422–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Truong, D.H.; Le, V.K.H.; Pham, T.T.; Dao, A.H.; Pham, T.P.D.; Tran, T.H. Delivery of Erlotinib for Enhanced Cancer Treatment: An Update Review on Particulate Systems. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 101348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punganuru, S.R.; Madala, H.R.; Mikelis, C.M.; Dixit, A.; Arutla, V.; Srivenugopal, K.S. Conception, Synthesis, and Characterization of a Rofecoxib-Combretastatin Hybrid Drug with Potent Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) Inhibiting and Microtubule Disrupting Activities in Colon Cancer Cell Culture and Xenograft Models. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 26109–26129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tołoczko-Iwaniuk, N.; Dziemiańczyk-Pakieła, D.; Nowaszewska, B.K.; Celińska-Janowicz, K.; Miltyk, W. Celecoxib in Cancer Therapy and Prevention—Review. Curr. Drug Targets 2018, 20, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaab, H.O.; Al-Hibs, A.S.; Alzhrani, R.; Alrabighi, K.K.; Alqathama, A.; Alwithenani, A.; Almalki, A.H.; Althobaiti, Y.S.; Alsaab, H.O.; Al-Hibs, A.S.; et al. Nanomaterials for Antiangiogenic Therapies for Cancer: A Promising Tool for Personalized Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S.; Lee, K.J.; Kalishwaralal, K.; Sheikpranbabu, S.; Vaidyanathan, R.; Eom, S.H. Antiangiogenic Properties of Silver Nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6341–6350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yao, Q.; Cao, F.; Liu, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.H. Silver Nanoparticles Inhibit the Function of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 and Target Genes: Insight into the Cytotoxicity and Antiangiogenesis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 6679–6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalishwaralal, K.; Banumathi, E.; Pandian, S.B.R.K.; Deepak, V.; Muniyandi, J.; Eom, S.H.; Gurunathan, S. Silver Nanoparticles Inhibit VEGF Induced Cell Proliferation and Migration in Bovine Retinal Endothelial Cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2009, 73, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, A.; Sadeghinia, A.; Kahroba, H.; Samadi, A.; Heidari, H.R.; Bradaran, B.; Zeinali, S.; Molavi, O. Therapeutic Targeting of Angiogenesis Molecular Pathways in Angiogenesis-Dependent Diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 110, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund International Worldwide Cancer Data, Global Cancer Statistics for the Most Common Cancers in the World. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/worldwide-cancer-data/ (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Ovais, M.; Khalil, A.T.; Raza, A.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, I.; Islam, N.U.; Saravanan, M.; Ubaid, M.F.; Ali, M.; Shinwari, Z.K. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles via Plant Extracts: Beginning a New Era in Cancer Theranostics. Nanomedicine 2016, 12, 3157–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-F.; Liu, Z.-G.; Shen, W.; Gurunathan, S. Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, Properties, Applications, and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barenholz, Y. Doxil®—The First FDA-Approved Nano-Drug: Lessons Learned. J. Control. Release 2012, 160, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianni, L.; Mansutti, M.; Anton, A.; Calvo, L.; Bisagni, G.; Bermejo, B.; Semiglazov, V.; Thill, M.; Chacon, J.I.; Chan, A.; et al. Comparing Neoadjuvant Nab-Paclitaxel vs. Paclitaxel Both Followed by Anthracycline Regimens in Women With ERBB2/HER2-Negative Breast Cancer—The Evaluating Treatment With Neoadjuvant Abraxane (ETNA) Trial: A Randomized Phase 3 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Singh, P.; Pandit, S.; Mokkapati, V.R.S.S.; Garg, A.; Ravikumar, V.; Mijakovic, I. Gold Nanoparticles in Diagnostics and Therapeutics for Human Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Fadaka, A.O.; Madiehe, M.A.; Maboza, E.; Meyer, M.; Geerts, G. Plant Extract-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles for Application in Dental Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiravan, V.; Ravi, S.; Ashokkumar, S. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Melia Dubia Leaf Extract and Their in Vitro Anticancer Activity. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 130, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, K.; Rather, H.A.; Rajagopal, K.; Shanthi, M.P.; Sheriff, K.; Illiyas, M.; Rather, R.A.; Manikandan, E.; Uvarajan, S.; Bhaskar, M.; et al. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles (Ag NPs) for Anticancer Activities (MCF 7 Breast and A549 Lung Cell Lines) of the Crude Extract of Syzygium Aromaticum. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017, 167, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj, M.; Rajesh, M.; Arun, R.; MubarakAli, D.; Sathishkumar, G.; Sivanandhan, G.; Dev, G.K.; Manickavasagam, M.; Premkumar, K.; Thajuddin, N.; et al. An Investigation on the Cytotoxicity and Caspase-Mediated Apoptotic Effect of Biologically Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Podophyllum Hexandrum on Human Cervical Carcinoma Cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 102, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaka, A.O.; Meyer, S.; Ahmed, O.; Geerts, G.; Madiehe, M.A.; Meyer, M.; Sibuyi, N.R.S. Broad Spectrum Anti-Bacterial Activity and Non-Selective Toxicity of Gum Arabic Silver Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Du, Z.; Ma, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Huang, H.; Jiang, S.; Cheng, S.; Wu, W.; Zhang, K.; et al. Effects of Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles on Lung Cancer Cells in Vitro and Grown as Xenograft Tumors in Vivo. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, J.S.; Bhimba, B.V. Anticancer Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by the Seaweed Ulva Lactuca Invitro. Open Access Sci. Rep. 2012, 1, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemlata; Meena, P.R.; Singh, A.P.; Tejavath, K.K. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Cucumis Prophetarum Aqueous Leaf Extract and Their Antibacterial and Antiproliferative Activity against Cancer Cell Lines. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 5520–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Venkatesan, B.; Subramanian, V.; Tumala, A.; Vellaichamy, E. Rapid Synthesis of Biocompatible Silver Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Extract of Rosa Damascena Petals and Evaluation of Their Anticancer Activity. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014, 7, S294–S300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanipandian, N.; Thirumurugan, R. A Feasible Approach to Phyto-Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Industrial Crop Gossypium Hirsutum (Cotton) Extract as Stabilizing Agent and Assessment of Its in Vitro Biomedical Potential. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 55, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenatchi, R.; Vijistella Bai, G. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanostructures against Human Cancer Cell Lines and Certain Pathogens. IJPCBS 2014, 4, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.; Mehdi, S.J.; Irshad, M.; Ali, A.; Sardar, M.; Rizvi, M.M.A. Effect of Biologically Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles on Human Cancer Cells. Sci. Adv. Mater. 2012, 4, 1200–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadharshini, R.I.; Prasannaraj, G.; Geetha, N.; Venkatachalam, P. Microwave-Mediated Extracellular Synthesis of Metallic Silver and Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Macro-Algae (Gracilaria Edulis) Extracts and Its Anticancer Activity Against Human PC3 Cell Lines. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 174, 2777–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Shan, W.; Li, L.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y. Efficient Mucus Permeation and Tight Junction Opening by Dissociable “Mucus-Inert” Agent Coated Trimethyl Chitosan Nanoparticles for Oral Insulin Delivery. J. Control. Release 2016, 222, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, N.; Silveira, C.P.; Durán, M.; Martinez, D.S.T. Silver Nanoparticle Protein Corona and Toxicity: A Mini-Review. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- AshaRani, P.V.; Mun, G.L.K.; Hande, M.P.; Valiyaveettil, S. Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of Silver Nanoparticles in Human Cells. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, T.; Li, N.; Nel, A.E. Potential Health Impact of Nanoparticles. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2009, 30, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairuangkitti, P.; Lawanprasert, S.; Roytrakul, S.; Aueviriyavit, S.; Phummiratch, D.; Kulthong, K.; Chanvorachote, P.; Maniratanachote, R. Silver Nanoparticles Induce Toxicity in A549 Cells via ROS-Dependent and ROS-Independent Pathways. Toxicol. Vitr. 2013, 27, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.F.; Shen, W.; Gurunathan, S. Silver Nanoparticle-Mediated Cellular Responses in Various Cell Lines: An in Vitro Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsin, Y.H.; Chen, C.F.; Huang, S.; Shih, T.S.; Lai, P.S.; Chueh, P.J. The Apoptotic Effect of Nanosilver Is Mediated by a ROS- and JNK-Dependent Mechanism Involving the Mitochondrial Pathway in NIH3T3 Cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2008, 179, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Yi, J.; Kim, Y.; Choi, K.; Park, K. Silver Nanoparticles Induce Cytotoxicity by a Trojan-Horse Type Mechanism. Toxicol. Vitr. 2010, 24, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hembram, K.C.; Kumar, R.; Kandha, L.; Parhi, P.K.; Kundu, C.N.; Bindhani, B.K. Therapeutic Prospective of Plant-Induced Silver Nanoparticles: Application as Antimicrobial and Anticancer Agent. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, S38–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McShan, D.; Ray, P.C.; Yu, H. Molecular Toxicity Mechanism of Nanosilver. J. Food Drug Anal. 2014, 22, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, P.P.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Harsha, S.N.; Policegoudra, R.S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Karak, N.; Chattopadhyay, A. Mentha Arvensis (Linn.)-Mediated Green Silver Nanoparticles Trigger Caspase 9-Dependent Cell Death in MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 Cells. Breast Cancer 2017, 9, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Govindappa, M.; Hemashekhar, B.; Arthikala, M.K.; Ravishankar Rai, V.; Ramachandra, Y.L. Characterization, Antibacterial, Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, Anti-Inflammatory and Antityrosinase Activity of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Calophyllum Tomentosum Leaves Extract. Results Phys. 2018, 9, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saratale, R.G.; Shin, H.S.; Kumar, G.; Benelli, G.; Kim, D.S.; Saratale, G.D. Exploiting Antidiabetic Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Punica Granatum Leaves and Anticancer Potential against Human Liver Cancer Cells (HepG2). Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Balan, K.; Qing, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Palvannan, T.; Wang, Y.; Ma, F.; Zhang, Y. Antidiabetic Activity of Silver Nanoparticles from Green Synthesis Using Lonicera Japonica Leaf Extract. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 40162–40168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengottaiyan, A.; Aravinthan, A.; Sudhakar, C.; Selvam, K.; Srinivasan, P.; Govarthanan, M.; Manoharan, K.; Selvankumar, T. Synthesis and Characterization of Solanum Nigrum-Mediated Silver Nanoparticles and Its Protective Effect on Alloxan-Induced Diabetic Rats. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2015, 6, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campoy, A.H.G.; Gutierrez, R.M.P.; Manriquez-Alvirde, G.; Ramirez, A.M. Original Research [Highly-Accessed] Protection of Silver Nanoparticles Using Eysenhardtia Polystachya in Peroxide-Induced Pancreatic β-Cell Damage and Their Antidiabetic Properties in Zebrafish. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 2601–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grace, B.; Viswanathan, M.; Wilson, D.D. A New Silver Nano-Formulation of Cassia Auriculata Flower Extract and Its Anti-Diabetic Effects. Recent Pat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero-Miliani, L.; Nielsen, O.H.; Andersen, P.S.; Girardin, S.E. Chronic Inflammation: Importance of NOD2 and NALP3 in Interleukin-1β Generation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2007, 147, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, R.; Xie, Y.; Lu, B.; Li, Q.; Chen, F.; Li, L.; Hu, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, Q.; Ye, W.; et al. Metabolic Inflammatory Syndrome: A Novel Concept of Holistic Integrative Medicine for Management of Metabolic Diseases. AME Med. J. 2018, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Olefsky, J. Chronic Tissue Inflammation and Metabolic Disease. Genes Dev. 2021, 35, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyavambiza, C.; Dube, P.; Goboza, M.; Meyer, S.; Madiehe, A.M.; Meyer, M. Wound Healing Activities and Potential of Selected African Medicinal Plants and Their Synthesized Biogenic Nanoparticles. Plants 2021, 10, 2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franková, J.; Pivodová, V.; Vágnerová, H.; Juráňová, J.; Ulrichová, J. Effects of Silver Nanoparticles on Primary Cell Cultures of Fibroblasts and Keratinocytes in a Wound-Healing Model. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2016, 14, e137–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhalaf, M.I.; Hussein, R.H.; Hamza, A. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles by Nigella Sativa Extract Alleviates Diabetic Neuropathy through Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Effects. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 2410–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparna, M.K.; Seethalakshmi, S.; Gopal, V. Evaluation of In-Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesised Using Piper Nigrum Extract. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, B.; David, L.; Vulcu, A.; Olenic, L.; Perde-Schrepler, M.; Fischer-Fodor, E.; Baldea, I.; Clichici, S.; Filip, G.A. In Vitro and in Vivo Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Viburnum Opulus L. Fruits Extract. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 79, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiuță, I.; Cristea, D. Silver Nanoparticles for Delivery Purposes. Nanoeng. Biomater. Adv. Drug Deliv. 2020, 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering Precision Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 20, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, N.; Gugleva, V.; Dobreva, M.; Pehlivanov, I.; Stefanov, S.; Andonova, V. Silver Nanoparticles as Multi-Functional Drug Delivery Systems. In Nanomedicines; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, S.; Hanif, R. Green Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Conjugated to Gefitinib as Delivery Vehicle. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2017, 5, 2321–9009. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous, Z.; Nemmar, A. Health Impact of Silver Nanoparticles: A Review of the Biodistribution and Toxicity Following Various Routes of Exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, X.; Shi, J.; Zou, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H. Silver Nanoparticles Interact with the Cell Membrane and Increase Endothelial Permeability by Promoting VE-Cadherin Internalization. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 317, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekamge, S.; Miranda, A.F.; Abraham, A.; Li, V.; Shukla, R.; Bansal, V.; Nugegoda, D. The Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) to Three Freshwater Invertebrates with Different Life Strategies: Hydra Vulgaris, Daphnia Carinata, and Paratya Australiensis. Front. Environ. Sci. 2018, 6, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mao, B.H.; Chen, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Yan, S.J. Silver Nanoparticles Have Lethal and Sublethal Adverse Effects on Development and Longevity by Inducing ROS-Mediated Stress Responses. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khan, S.U.; Saleh, T.A.; Wahab, A.; Khan, M.H.U.; Khan, D.; Khan, W.U.; Rahim, A.; Kamal, S.; Khan, F.U.; Fahad, S. Nanosilver: New Ageless and Versatile Biomedical Therapeutic Scaffold. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 733–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bruna, T.; Maldonado-Bravo, F.; Jara, P.; Caro, N. Silver Nanoparticles and Their Antibacterial Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Luna, P.I.; Martinez-Castanon, G.A.; Zavala-Alonso, N.V.; Patiño-Marin, N.; Niño-Martínez, N.; Morán-Martínez, J.; Ramírez-González, J.H. Bactericide Effect of Silver Nanoparticles as a Final Irrigation Agent in Endodontics on Enterococcus Faecalis: An Ex Vivo Study. J. Nanomater. 2016, 2016, 7597295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, J.L.; Grainger, D.W. In Vivo Comparisons of Silver Nanoparticle and Silver Ion Transport after Intranasal Delivery in Mice. J. Control. Release 2018, 269, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge de Souza, T.A.; Rosa Souza, L.R.; Franchi, L.P. Silver Nanoparticles: An Integrated View of Green Synthesis Methods, Transformation in the Environment, and Toxicity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 171, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypij, M.; Jędrzejewski, T.; Trzcińska-Wencel, J.; Ostrowski, M.; Rai, M.; Golińska, P. Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles: Antibacterial and Anticancer Activities, Biocompatibility, and Analyses of Surface-Attached Proteins. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microbes | Strain | AgNPs Size (nm) | AgNPs Shape | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Arthrospira indica | 48−67 | Spherical | [39] |

| Pseudomonas mandelii | 1.9−10 | Spherical, irregular | [36] | |

| Fungi | Penicillium expansum | 14−25 | Spherical, irregular | [37] |

| Aspergillus niger | 25−175 | Spherical | [40] |

| Species | Type | Plant Source | Hydrodynamic Size (nm) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plants | Allium cepa | Onion | 5–80 | [15] |

| Solanum lycopersicum L. | Tomato | 2–50 | ||

| Acacia catechu | Acacia catechu powder | 5–80 | ||

| Cotyledon orbiculata | Plant leaves | 100–140 | [17] | |

| Pyrus communis L. cultivars | Fruit pulp and skins | 110–190 | [16] | |

| Terminalia mantaly | Root, stem bark, leaves | 11–83 | [18] | |

| Algae | Coelastrum sp. | Algae cultures | 19.2 | [48] |

| Spirulina sp. | 13.85 | |||

| Botryococcus braunii | 15.67 |

| Plant Material | Plant Extract | Test Bacteria | Shape of AgNPs | Size of AgNPs (nm) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcuma Longa | Turmeric powder extract | E. coli Listeria monocytogenes | Mostly spherical with quasi-spherical, decahedral, ellipsoidal, and triangular shapes | 5–35 | [56] | |

| Pyrus communis L. cultivars | Fruit peel and pulp | S. aureus, MRSA, P. aeruginosa, E. coli | Spherical | 110–190 | [16] | |

| Terminalia Mantaly | Stem bark, leaves, and roots | S. aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella enterica, Shigella flexneri, Hoemophilus influenza | Polydispersed | 11–83 | [18] | |

| Salvia Africana Lutea | Leaves | Staphylococcus epidermidis, P. aeruginosa | Polygon and spherical | 25–40 | [57] | |

| Sutherlandia frutescens | Leaves | S. epidermidis, P. aeruginosa | Spherical | 200–400 | [57] | |

| Sapindus mukorossi | fruit pericarp extract | S. Aureus, P. aeruginosa | Spherical | ≤30 | [58] | |

| Grape fruit | peel extract | E. coli, S. aureus, Enterococcus faecalis | - | 0–100 | [59] | |

| Areca catechu | fruits extract | E. faecalis, Vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis, P. aeruginosa, Multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii | Spherical | 100–300 | [20] | |

| Ipomoea aquatica | leaf extract | Salmonella, Staphylococcus sp., E. coli | Spherical | 5–30 | [60] | |

| Acacia lignin | wood dust | Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus circulans, S. aureus, E. coli, Ralstonia eutropha, P. aeruginosa | Spherical | 2–26 | [61] | |

| Amaranthus Tricolor L. | Red spinach leaf extract | E. coli | Spherical | 5–40 | [62] | |

| Anti-Angiogenesis Drugs | Angiogenesis Inhibitory Strategies | References |

|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab (Avastin) | Target VEGF and inhibits formations of VEGF complexes such as VEGF-A and VEGF-2 | [88] |

| Semaxanib, Sunitinib, Sorafenib, Vatalanib | Inhibition of receptor tyrosine kinase | [89,90,91] |

| GEM 220 | Inhibition of VEGF | [92,93] |

| Endostatin | Inhibition of endothelial-cell survival | [94] |

| Erlotinib, Gefitinib | Inhibitors of EGFR | [95] |

| Celecoxib, Rofecoxib | COX-2 inhibitors | [96,97] |

| Cancer | Plant | AgNPs Size (nm) | AgNPs Shape | Cell Line | IC50 (μg/mL) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Achillea biebersteinii | 12 | Spherical, pentagonal | MCF-7 | 20 | [80] |

| Melia dubia | 7.3 | Irregular | 31.2 | [110] | ||

| Ulva lactuca | 56 | Spherical | 37 | [115] | ||

| Liver cancer | Cucumis prophetarum | 30–50 | Polymorphic shape (ellipsoidal, irregular) | HepG-2 | 94.2 | [116] |

| Lung cancer | Rosa damascene | 15–27 | Spherical | A549 | 80 | [117] |

| Gossypium hirsutum | 13–40 | Spherical | 40 | [118] | ||

| Syzygium aromaticum | 5–20 | Spherical | 70 | [111] | ||

| Cervical cancer | Podophyllum hexandrum | 14 | Spherical | HeLa | 20 | [112] |

| Heliotropium indicum | 80–120 | Spherical | Siha | 20 | [119] | |

| Azadirachta indica | 2–18 | Triangular and hexagonal | ≤4.25 | [120] | ||

| Colon cancer | Gum arabic | 1–30 | Spherical | HT-29 Caco-2 | 1.55 1.26 | [113] |

| Prostate cancer | Alternanthera sessilis | 50–300 | Spherical | PC-3 | 6.85 | [26] |

| Gracilaria edulis | 55–99 | Spherical | PC-3 | 53.99 | [121] | |

| Dimocarpus longan | 8–22 | Spherical | VCaP | 87.33 | [114] |

| Plant Type | Core Size (nm) | Hydrodynamic Size (nm) | AgNPs Inhibitory Effect | Test Sample | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calophyllum tomentosum leaves extract | - | 24 | α-amylase | Starch | [133] |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase IV | Gly-Pro-P-Nitroanilide | ||||

| α-glucosidase | 4-nitrophenyl-α-d glycopyranoside | ||||

| Punica granatum leaves | 20–45 | α-amylase | Starch | [134] | |

| 35–60 | α-glucosidase | para-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside | |||

| Grape Pomace | 5–40 | - | inhibits α-amylase and α-glucosidase | α-amylase and α-glucosidase | [25] |

| Solanum nigrum | 4–25 | - | Glucose inhibition | alloxan-induced diabetic rats | [136] |

| Bark of Eysenhardtia polystachya | 5–25 | 36.2 | Promote pancreatic β-cell survival; Restores insulin secretion in INS-1 cells | Glucose-induced adult Zebrafish (hyperglycemia) | [137] |

| Status | Study Title | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | AgNPs Formulation | Condition | Participants | Administration Route | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active, recruiting | Colloidal silver, treatment for COVID-19 | NCT04978025 | AgNPs | Severe acute respiratory syndrome | 50 | Oral and inhalation | N/A |

| Completed | Topical application of silver nanoparticles and oral pathogens in ill patients | NCT02761525 | 12 ppm of AgNPs- innocuous gel | Critical illness | 50 | Oral mucosa | N/A |

| Silver nanoparticles in multi-drug-resistant bacteria | NCT04431440 | AgNPs | Methicillin and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus | 150 | Tested on clinical isolates | N/A | |

| Nano-silver fluoride to prevent dental biofilms growth | NCT01950546 | 5% nanosilver fluoride (390 mg/mL 9 nm AgNPs, 21 mg/mL chitosan, 22 mg/mL NaF) | Dental caries | 30 | Applied on cervical vestibular surfaces of incisors and canines | 1 | |

| The anti-bacterial effect of nano-silver fluoride on primary teeth | NCT05221749 | Nano-silver fluoride | Dental caries in children (1–12 years old) | 50 | Oral | 3 | |

| Evaluation of silver nanoparticles for the prevention of COVID-19 | NCT04894409 | ARGOVIT® AgNPs (Mouthwash and nose rinse) | COVID-2019 | 231 | Mouthwash and nose rinse | N/A | |

| Assessment of postoperative pain after using various intracanal medications in patients with necrotic pulp | NCT03692286 | AgNPs and calcium hydroxide vs. AgNPs in gel form | Necrotic pulp (postoperative pain) | 30 | Intracanal medication | 4 | |

| Effect of thyme and carvacrol nanoparticles on aspergillus fumigatus isolate from intensive care patients | NCT04431804 | AgNPs | Aspergillosis | 210 | Aspergillus isolates | N/A | |

| Evaluation of diabetic foot wound healing using hydrogel and nano silver-based dressing vs. traditional dressing | NCT04834245 | Hydrogel and nano silver-based dressing | Diabetic wounds | 30 | Topical wound dressing | N/A | |

| Comparison of central venous catheters (CVC) with silver nanoparticles versus conventional catheters | NCT00337714 | CVC impregnated with AgNPs (AgTive®) | CVC related infections | 472 | Cannulation | 4 | |

| Unknown | Topical silver nanoparticles for microbial activity | NCT03752424 | AgNPs-cream | Fungal infection (Tinea pedis, Capitis and Versicolor) | 30 | Topical | 1 |

| Research on the key technology of burn wound treatment | NCT03279549 | Nano-silver ion gel and dressings | Burns | 200 | Topical | N/A | |

| Addition of silver nanoparticles to an orthodontic primer in preventing enamel demineralisation adjacent brackets | NCT02400957 | AgNPs incorporated into the primer orthodontic Transbond XT | Tooth demineralisation | 40 | Dental application | 3 | |

| Fluor varnish with silver nanoparticles for dental remineralisation in patients with Trisomy 21 | NCT01975545 | 25% of 50 nm AgNPs in fluor varnish | Dental remineralisation in patients with Down syndrome | 20 | Oral varnish | 2 | |

| Efficacy of silver nanoparticle gel versus a common anti-bacterial hand gel | NCT00659204 | Nano-silver gel (SilvaSorb® gel) | Healthy | 40 | Topical on hands | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simon, S.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Fadaka, A.O.; Meyer, S.; Josephs, J.; Onani, M.O.; Meyer, M.; Madiehe, A.M. Biomedical Applications of Plant Extract-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2792. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10112792

Simon S, Sibuyi NRS, Fadaka AO, Meyer S, Josephs J, Onani MO, Meyer M, Madiehe AM. Biomedical Applications of Plant Extract-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Biomedicines. 2022; 10(11):2792. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10112792

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimon, Sohail, Nicole Remaliah Samantha Sibuyi, Adewale Oluwaseun Fadaka, Samantha Meyer, Jamie Josephs, Martin Opiyo Onani, Mervin Meyer, and Abram Madimabe Madiehe. 2022. "Biomedical Applications of Plant Extract-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles" Biomedicines 10, no. 11: 2792. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10112792

APA StyleSimon, S., Sibuyi, N. R. S., Fadaka, A. O., Meyer, S., Josephs, J., Onani, M. O., Meyer, M., & Madiehe, A. M. (2022). Biomedical Applications of Plant Extract-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Biomedicines, 10(11), 2792. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10112792