The EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child and the European Child Guarantee—Evidence-Based Recommendations for Alternative Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Alternative Care: Concepts

1.2. The Portuguese Context

1.2.1. What Are Facts and Figures Saying?

1.2.2. The Portuguese National Strategy on the Rights of the Child

2. Materials and Methods

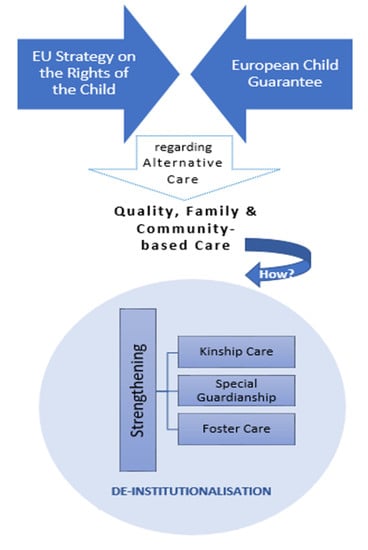

3. The EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child and the European Child Guarantee

Alternative Care within the EU Strategy and the Guarantee

4. Addressing the EU Strategy and the Guarantee into the Portuguese Alternative Care

4.1. Strengthening Kinship Care: Family Members and Reliable Persons

4.2. Room for Special Guardianship

4.3. Foster Care—What Is Still to Be Done?

- Investing resources so foster care is available widely;

- Providing adequate financing;

- Regulating and monitoring;

- Providing flexible placements to address children’s needs (e.g., emergency placements, respite care, short term and longer-term placements);

- Ensuring children and foster carers participation and mechanisms for complaints; requiring that siblings are placed together;

- Guaranteeing children have contact with their parents, wider family, friends and community;

- Providing appropriate support and training for carers, especially for those who care for children with disabilities and other special needs, and including topics on child development and attachment, children’s rights and child well-being;

- Ensuring day care and respite care, health and education services whenever needed.

4.4. Global Dimensions of Alternative Care

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Priority | Strategic Aim | Support References |

|---|---|---|

| Priority I promote wellbeing and equal opportunities | SA1 Ensure a standard of living suitable to the development of children, through an efficient allocation of social and fiscal support | Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) 26.1; CRC 27; Recommendation (REC) 16; REC 58 |

| SA2 Promote a safety and healthy environment | CRC 28; REC 30 | |

| SA3 Invest in prevention and promote physical and mental health support in childhood, in order to develop healthy generations | CRC 24; CRC 25; REC 50; CRC 19.2; REC 52; CRC 33; REC 54; CRC 28 | |

| SA4 Ensure children access to quality playful, entertaining and sporting activities | CRC 31; CRC 29; REC 26 | |

| SA5 Ensure access to quality inclusive education to all children, contributing for their physical, cognitive, social and emotional development | CRC 28; REC 60 (b); CRC 29; REC 60 (c); REC 60 (d); CRC 26.2; CRC 27 | |

| SA6 Qualify and reinforce measures, programmes, services and social responses, as well as support for disabled children and their families | CRC 23; REC 46 | |

| SA7 Support migrants children integration, including refugees and asylum seekers, descent of migrants and Roma | CRC 2; CRC 8; CRC 29; CRC 30 REC 26 | |

| Priority II support families and parenthood | SA8 Foment competences for a positive parenthood and shared parenthood responsability | CRC 18.2; REC 40 |

| SA9 Qualify measures, programmes, and social and health responses for children within an integrated family approach | CRC 26; CRC 18.3; REC 16; CRC 24; REC 56; CRC 6; CRC 27; CRC 20; REC 42; CRC 21; REC 44; CRC 25; REC 42 (d) | |

| Priority III promote access to information and to participation for children | SA10 Promote information and training on the rights of children | CRC 42; REC 22; Lanzarote Convention (LC) 9; CRC 28; CRC 29; REC 30 (a); CRC 2; CRC 4; CRC 3.1; CRC 19 |

| SA11 Promote participation and exercise of citizenship of children | CRC 2; CRC 8; CRC 13; CRC 14; CRC 29; CRC 42; REC 26 (a); REC 26 (b); REC 60 (e); CRC 7; CRC 12; REC 32 (a); REC 32 (b); REC 32 (c); CRC 12; REC 32; LC 9; LC 35; CRC 4; CRC 12; CRC 40; REC 10; REC 32 (a); REC 66; CRC 15; CRC 31 | |

| Priority IV prevent and combat violence against children | SA12 Prevent and act on different forms of violence against children, promoting a non-violence culture | CRC 34; CRC 35; CRC 36; CRC 39 REC 24; REC 26 (b); REC 36; LC 4, 5, 6, 7 e 8; Optional Protocol on Sales of Children (OP -SC); CRC 19; CRC 29; REC 60 (e); REC 46; CRC 28.2; CRC 17; CRC 4 |

| SA13 Promote knowleadge on different forms of violence against children and qualify responses | CRC 19; REC 28; REC 46; CRC 39; CRC 42; REC 26 (b); LC5C; REC 24 | |

| Priority V promote instruments and scientific knowledge production for a global view on the rights of children | SA14 Tailor national legislation on children to the CRC | CRC 34; CRC 40; REC 10; REC 36 OP-SC; LC 31 |

| SA15 Concept and implement a data gathering and analysis system on children | CRC 4; CRC 17; REC 18; LC 10.2 |

References

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions EU strategy on the Rights of the Child (COM/2021/142 final). European Union, European Commission. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0142 (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Council Recommendation 2021/1004. Establishing a European Child Guarantee. European Union, Council of the European Union. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reco/2021/1004/oj (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Dolan, K. Group Homes in the Foster Care System: A Literature Review. Locus Seton Hall J. Undergrad. Res. 2020, 3, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, M.J.; Diogo, E. Acolhimento Familiar de Crianças e Jovens: O nó cego da proteção à infância em Portugal. In Acolhimento Familiar de Crianças e Jovens em Perigo—Manual Para Profissionais; Magalhães, E., Baptista, J., Eds.; Pactor: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bergström, M.; Cederblad, M.; Håkansson, K.; Jonsson, A.K.; Munthe, C.; Vinnerljung, B.; Wirtberg, I.; Östlund, P.; Sundell, K. Interventions in Foster Family Care: A Systematic Review. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2019, 30, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, N.; Davidson, J.; Elsley, S.; Milligan, I.; Quinn, N. Moving Forward: Implementing the ‘Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children’; Centre for Excellence for Looked After Children in Scotland: Glasgow, UK, 2012; Available online: https://www.alternativecareguidelines.org/Portals/46/Moving-forward/Moving-Forward-implementing-the-guidelines-for-web1.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- United Nations General Assembly. Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children. Resolution A/RES/64/142. 2009. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol%20=%20A/RES/64/142 (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- European Social Network. Developing Community Care. European Social Network. 2011. Available online: https://www.esn-eu.org/sites/default/files/publications/2011_Developing_Community_Care_Report_EN.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Gilligan, R. “The De-institutionalization Process in Ireland”—What have we learned? In Proceedings of the De-Institutionalization of Childcare: Investing in Change, Sofia, Bulgaria, 6–8 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Negrão, M.; Moreira, M.; Veríssimo, L.; Veiga, E. Conhecimentos e perceções públicas acerca do acolhimento familiar: Contributos para o desenvolvimento da medida. Anal. Psicol. 2019, 37, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freitas, S. Why Do People Become Foster Parents? From the Literature to Empirical Evidence. Master’s Thesis, ISCTE-IUL, Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, M. Crescer em Famílias de Acolhimento: Histórias de Vida de Jovens—Adultos. Master’s Thesis, Instituto de Educação—Universidade do Minho, Lisbon, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, G.; Beek, M.; Sargent, K.; Thoburn, J. Growing Up in Foster Care; BAAF: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, R.; Groark, C.; Rygaard, N. Global Research, Practice, and Policy Issues on the Care of Infants and Young Children at Risk: The Articles in Context. Infant Ment. Health J. 2014, 35, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, I.; Belsky, J.; Oliveira, P.; Silva, J.; Marques, S.; Baptista, J.; Martins, C. Does early family risk and current quality of care predict indiscriminate social behavior in institutionalized Portuguese children? Attach. Hum. Dev. 2014, 16, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davidson, J.C.; Milligan, I.; Quinn, N.; Cantwell, N.; Elsley, S. Developing family-based care: Complexities in implementing the UN Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2016, 20, 754–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Terziev, V.; Arabska, E. Process of Deinstitutionalization of Children at Risk in Bulgaria. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 233, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Resolução do Conselho de Ministros no. 112/2020 Diário da República, 18 December 2020, 1.ª série, 245. pp. 2–22. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/1s/2020/12/24500/0000200022.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Decreto-Lei no. 189/91, of 17th May, Diário da República, 113, Série I-A. 1991, pp. 2635–2640. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/1s/1991/05/113a00/26352640.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Gersão, E.; Sacur, B.M. Promoção de direitos e proteção de crianças e jovens: Passado, presente e cami-nhos de futuro [Promotion of rights and protection of children and youth: Past, present and future paths]. In Atores e Dinâmicas no Sistema de Promoção e Proteção de Crianças e Jovens; Francisco, R., Pinto, H.R., Eds.; Universidade Católica Editora: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021; pp. 62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lei no. 147/99, of 1st September, Diário da República, 204, Série I-A. 1999, pp. 6115–6132. Available online: http://www.pgdlisboa.pt/leis/lei_mostra_articulado.php?nid=545&tabela=leis (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Lei no. 31/2003, of 22nd of August, Diário da República, 193, Série I-A. 2003, pp. 5313–5329. Available online: http://www.pgdlisboa.pt/leis/lei_mostra_articulado.php?nid=546&tabela=leis (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Lei no. 142/2015, of 8th September, Diário da República, 175, Série I. 2015, pp. 7198–7232. Available online: https://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/9597919/Lei_n_142_2015_09_08/7059a660-0ddc-4547-9a99-ded7aec210ad (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Lei, no. Lei no. 23/2017, of 23th of May, Diário da República, 99, Série I. 2017, p. 2494. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/1s/2017/05/09900/0249402494.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Lei, no. Lei no. 26/2018, of 5th July, Diário da República, 128, 1.ª série. 2018, pp. 2902–2903. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/1s/2018/07/12800/0290202903.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- Lei no. 103/2009, of 11th September, Diário da República, 177, Série I. 2009, pp. 6210–6216. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/legislacao-consolidada/lei/2009-34513875 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Decreto-Lei no. 121/2010, of 27th October, Diário da República, 209, Série I. 2010, pp. 4892–4894. Available online: https://www.pgdlisboa.pt/leis/lei_mostra_articulado.php?nid=1287&tabela=leis&so_miolo= (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Oliveira, G. Adoção e Apadrinhamento Civil [Adoption and Special Guardianship]; Petrony Editora: Vila Franca de Xira, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, I.; Pearce, J. Violence and Alternative Care: A Rapid Review of the Evidence. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Regional Office. The European Child Guarantee Phase III of the Preparatory Action: “Testing the EU Child Guarantee in the EU Member States”. 2021. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eca/european-child-guarantee (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- CNPDPCJ—Comissão Nacional de Promoção dos Direitos e Proteção das Crianças e Jovens. Relatório Anual de Avaliação da Atividade das CPCJ 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.cnpdpcj.gov.pt/documents/10182/16406/Relat%C3%B3rio+Anual+da+Atividade+das+CPCJ+do+ano+2020/2a522cda-e8ba-40fe-9389-47fa5966f7ed (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Pordata. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/Portugal/Popula%c3%a7%c3%a3o+residente++m%c3%a9dia+anual+total+e+por+grupo+et%c3%a1rio-10-1141 (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- DGPJ-Direção Geral de Política de Justiça. Movimento de Processos de Promoção e Proteção nos Tribunais Judiciais de 1.ª Instância, nos anos de 2011 ao 1º Trimestre de 2021; Direção Geral de Política de Justiça: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021.

- ISS—Instituto da Segurança Social, Instituto Público. CASA, 2020—Relatório de Caracterização Anual da Situação de Acolhimento das Crianças e Jovens. 2021. Available online: https://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/13200/CASA+2020.pdf/b7f02f58-2569-4165-a5ab-bed9efdb2653 (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Decreto-lei no. 139/2019, 16th of September, Diário da República, 177, Série I. 2019, pp. 11–29. Available online: http://www.pgdlisboa.pt/leis/lei_mostra_articulado.php?artigo_id=3204A0035&nid=3204&tabela=leis&pagina=1&ficha=1&so_miolo=&nversao= (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Portaria no. 278-A/2020, 4th of December, Diário da República, 236, Série I. 2020, pp. 2–15. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/detalhe/portaria/278-a-2020-150343971 (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Diogo, E. Ser Família de Acolhimento em Portugal, Motivações e Experiências [Being a Foster Family in Portugal—Motivations and Experiences]; Universidade Católica Editora: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education. Children Looked after in England (Including Adoption), Year Ending 31 March 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoption-2018-to-2019 (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Furey, E.; Canavan, J. A Review on the Availability and Comparability of Statistics on Child Protection Welfare, Including Children in Care Collated by Tusia: Child and Family Agency with Statistics Published in Other Jurisdictions; UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre: NUI Galway, Ireland, 2019; Available online: https://www.tusla.ie/uploads/content/COMPWELFINALREPORTMARCH29_-_Final.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Ministerio de Derechos Sociales y Agenda 2030. Boletín de Datos Estadísticos de Medidas de Protección a la Infancia. Boletín número 22, Datos 2019. 2020. Available online: https://observatoriodelainfancia.vpsocial.gob.es/productos/pdf/BOLETIN_22_final.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- United Nations, Committee on the Rights of the Child. Concluding Observations on the Combined Third and Fourth Periodic Report of Portugal. CRC/C/PRT/CO/3-4. Available online: https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CRC/Shared%20Documents/PRT/CRC_C_PRT_CO_3-4_16303_E.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- United Nations, Committee on the Rights of the Child. Concluding Observations on the Combined Fifth and Sixth Periodic Report of Portugal. CRC/C/PRT/CO/5-6. 2019. Available online: https://www.provedor-jus.pt/documentos/Observacoes_Finais_Comite_Dtos_Crianca.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989. Available online: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Flick, U. Métodos Qualitativos na Investigação Científica; Monitor: Lisbon, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPACCRC.aspx (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography. 2000. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/OPSCCRC.aspx (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on a Communications Procedure. 2012. Available online: https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/crc/docs/CRC-OP-IC-ENG.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2006. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/hrbodies/crpd/pages/conventionrightspersonswithdisabilities.aspx (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Strategy for the Rights of the Child (2016–2021). 2016. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=090000168066cff8 (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- European Commission. Annex to the EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child. EU and International Frameworks. European Union, European Commission. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/childrights_annex1_2021_4_digital_0.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- European Union. Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, C326, 391–407. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution A/RES/70/1. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1andLang=E (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- European Commission. Annex to the EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child. EU Acquis and Policy Documents on the Rights of the Child. European Union, European Commission. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/childrights_annex2_2021_4_digital_0.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Chaves, S. Constrangimentos e Potencialidades Associados à Medida de Acolhimento Familiar de Crianças e Jovens. Master’s Thesis, ISCTE-IUL University Institute of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/bitstream/10071/17110/1/master_sara_pedro_chaves.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Li, D.; Chng, G.; Chu, C. Comparing Long-Term Placement Outcomes of Residential and Family Foster Care: A Meta-Analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenberg, A.; Partskhaladze, N. How the Republic of Georgia Has Nearly Eliminated the Use of Institutional Care for Children. Infant Ment. Health J. 2014, 35, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, V.; Bogdanov, G. The Deinstitutionalization of Children in Bulgaria—The Role of the EU. In Social Policy and Administration; 2013; Volume 47, pp. 199–217. ISSN 0144–5596. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/spol.12015 (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Skoglund, J.; Thørnblad, R. Kinship Care or Upbringing by Relatives? The Need for ‘New’ Understandings in Research. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2019, 22, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winokur, M.; Holtan, A.; Batchelder, K. Kinship Care for the Safety, Permanency, and Well-Being of Children Removed from the Home for Maltreatment: A Systematic Review. Retrieved from Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006546.pub3/epdf/abstract (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Bergthold, A. The Effect of Kinship Foster Care Compared to Non-Kinship Foster Care on Resiliency. Leadership Connection 2018. Available online: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1455&context=research_scholarship_symposium (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Xu, Y.; Bright, L. Children’s Mental Health and Its Predictors in Kinship and Non-Kinship Foster Care: A Systematic Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 89, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehl, C.; Shuman, T. Children Placed in Kinship Care: Recommended Policy Changes to Provide Adequate Support for Kinship Families. Child. Leg. Rights J. 2020, 39, 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto-Lei no. 11/2008, of 17th January, Diário da República, Série I. 2008, pp. 552–559. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/legislacao-consolidada/decreto-lei/2008-34455775-53087975. (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Decreto-Lei no. 12/2008, of 17th January, Diário da República, Série I. 2008, pp. 1256–1259. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/legislacao-consolidada/decreto-lei/2008-34455875. (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Xu, Y.; Bright, L.; Ahn, H.; Huang, H.; Shaw, T. A New Kinship Typology and Factors Associated with Receiving Financial Assistance in Kinship Care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 110, 1–11. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/cysrev/v110y2020ics0190740919312769.html (accessed on 10 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Alfaiate, A.R.; Ribeiro, G. Reflexões a Propósito do Apadrinhamento Civil [Reflections on Special Guardianship]. Rev. Do Cent. De Estud. Judiciários 2013, 1, 117–142. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11328/2185 (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Ferreira, E. O apadrinhamento civil como alternativa ao acolhimento permanente de crianças e jovens [Special Guardianship as an alternative to permanent care of children and youth]. Configurações 2019, 23, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C. Algumas notas em torno do Regime Jurídico do Apadrinhamento Civil [Some notes about special guar-dianship legal regime]. In Estudos em Homenagem ao Professor Doutor Heinrich Ewald Hörster; Gonçalves, L.C., Ed.; Almedina: Coimbra, Portugal, 2012; pp. 161–195. [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds, J.; Harwin, J.; Brown, R.; Broadhurst, K. Special Guardianship: A Review of the Evidence. Summary Report. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. 2019. Available online: https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/NuffieldFJO-Special-Guardianship-190731-WEB-final.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Simmonds, J.; Harwin, J. Making Special Guardianship Work for Children and Their Guardians. Briefing paper. Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. 2020. Available online: https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/making_special_guardianship_work_briefing_paper.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Lei no. 47/2019, of 8th July. Diário da República, 1.ª série, 128. 2019, p. 3415. Available online: https://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/16485882/Lei_47_2019.pdf/b0e3416d-6ef6-4080-873f-de81f1e5b21d. (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- European Commission Daphne Programme—Directorate-General Justice and Home Affairs. De-Institutionalising and Transforming Children’s Services—A Guide to Good Practice. University of Birmingham. 2007. Available online: https://www.globaldisabilityrightsnow.org/sites/default/files/related-files/262/De-institutionalizing%20and%20Transforming%20Children%E2%80%99s%20Services%20A%20Guide%20to%20Good%20Practice.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Gouveia, L.; Magalhães, E.; Pinto, V. Foster Families: A Systematic Review of Intention and Retention Factors. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 2766–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, E.; Branco, F. The Foster Family Process to Maintain the Will to Remain in Foster Care—Implications for a Sustainable Programme. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.; Randle, M.; Dolnicar, S. Carer Factors Associated with Foster-Placement Success and Breakdown. Br. J. Soc. Work 2019, 49, 503–522. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/buspapers/1486 (accessed on 14 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Diogo, E.; Branco, F. Being a Foster Family in Portugal—Motivations and Experiences. Societies 2017, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haysoma, Z.; McKibbinb, G.; Shlonskyc, A.; Hamiltond, B. Changing Considerations of Matching Foster Carers and Children: A Scoping Review of the Research and Evidence. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeijlmans, K.; López, M.; Grietens, H.; Knorth, E. Matching Children with Foster Carers: A Literature Review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 73, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeijlmans, K.; López, M.; Grietens, H.; Knorth, E. Participation of Children, Birth Parents and Foster Carers in the Matching Decision. Paternalism or Partnership? Child. Abus. Rev. 2019, 28, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Alternative Care Concepts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family-Based Care | Residential Care | |||

| Kinship Care | Foster Care | Other | ||

| Portuguese child protection and civil measures on alternative care | Support the child in care with other family member | Foster care | Special guardianship | Residential care |

| Entrust the child to a reliable and family person | ||||

| EU Stratrgy on the Rights of the Child ALL Children | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thematic areas | |||||

| Participation in political and democratic life: An EU that empowers children to be active citizens and members of democratic societies | Socioeconomic inclusion, health and education: An EU that fights child poverty, promotes inclusive and child-friendly societies, health and education systems | Combating violence against children and ensuring child protection: An EU that helps children grow free from violence | Child-friendly justice: An EU where the justice system upholds the rights and needs of children | Digital and information society: An EU where children can safely navigate the digital environment and harness its opportunities | The Global Dimension: An EU that supports, protects and empowers children globally, including during crisis and conflcit |

| European Child Guarantee | |||||

| Children in need, namely: | Access to key kervices: | ||||

| In alternative, especially instititional care | Homeless children | With disabilities | Free early education and care, education and school-based activities, healthcare and at least one healthy meal each school day | ||

| With mental health issues | With a migrant background or minority ethic origin (particularly Roma) | In precarious family situations | Adequate housing and healthy nutrition | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sacur, B.M.; Diogo, E. The EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child and the European Child Guarantee—Evidence-Based Recommendations for Alternative Care. Children 2021, 8, 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8121181

Sacur BM, Diogo E. The EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child and the European Child Guarantee—Evidence-Based Recommendations for Alternative Care. Children. 2021; 8(12):1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8121181

Chicago/Turabian StyleSacur, Bárbara Mourão, and Elisete Diogo. 2021. "The EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child and the European Child Guarantee—Evidence-Based Recommendations for Alternative Care" Children 8, no. 12: 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8121181

APA StyleSacur, B. M., & Diogo, E. (2021). The EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child and the European Child Guarantee—Evidence-Based Recommendations for Alternative Care. Children, 8(12), 1181. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8121181