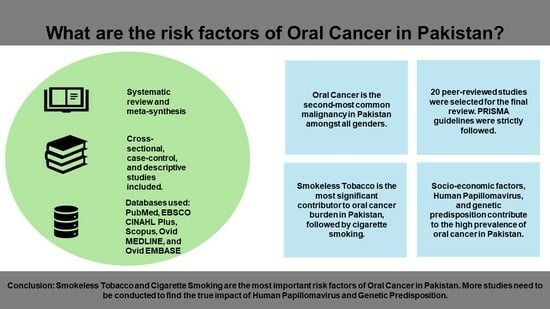

Exploring the Risk Factors for Oral Cancer in Pakistan: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Research Question

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Implementation of Eligibility Criteria

2.6. Data Extraction and Analysis

2.7. Critical Appraisal

2.8. Outcome of the Critical Appraisal

| Case–Control Studies: CASP Tool | Section A: Are the Results of the Trial Valid? | Section B: What Are the Results? | Section C: Will the Results Help Locally? | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | Did the Study Address a Clearly Focused Issue? | Did the Authors Use an Appropriate Method to Answer the Question? | Were the Cases Recruited in an Acceptable Way? | Were the Controls Selected in an Acceptable Way? | Was the Exposure Accurately Measured to Minimise Bias? | Aside from the Experimental Intervention, Were the Groups Treated Equally? | Have the Authors Taken Account of the Potential Confounding Factors in the Design and/or Their Analysis? | How Large Was the Treatment Effect? | How Precise Was the Estimate of the Treatment Effect? | Do You Believe the Results? | Can the Results be Applied to Local Population? | Do the Results of This Study Fit with Other Available Evidence? |

| Mugheri et al. (2018) [14] | + | + | + | + | + | +/- | - | Outcome significantly affected by exposure | Authors considered all important variables, a relatively narrow confidence interval indicating high precision | + | + | + |

| Awan et al. (2016) [15] | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | Exposure was highly significant for developing the outcome | Relatively narrow confidence intervals indicating high precision | + | + | + |

| Zakiullah et al. (2015) [10] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Exposures show association with the outcome | Narrow confidence intervals indicating high precision | + | + | + |

| Masood et al. (2011) [16] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Increased risk associated with exposure | Narrow confidence interval indicating high precision | + | + | + |

| Zil-e-Rubab et al. (2018) [17] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Increased risk associated with exposure | Narrow confidence interval indicating high precision | + | + | - |

| Sarwar et al. (2022) [18] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Increased risk associated with exposure | Narrow confidence interval indicating high precision | + | + | + |

| Khan et al. (2017) [19] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Increased risk associated with exposure | Wide confidence interval indicating low precision | + | + | + |

| Merchant et al. (2000) [20] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Outcome strongly associated with exposure | Relatively narrow confidence interval indicating high precision | + | + | + |

| Shahid et al. (2019) [21] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Outcome strongly associated with exposure | +/- | + | + | + |

| Azhar et al. (2018) [22] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Increased risk associated with exposure | +/- | + | + | + |

| Khan et al. (2020) [23] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Increased risk associated with exposure | Relatively wide confidence interval indicating low precision | + | + | + |

| Mehdi et al. (2019) [24] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Outcome strongly affected by exposure | Narrow confidence interval indicating high precision | + | + | + |

| Aqeel et al. (2017) [12] | - | +/- | + | + | + | + | - | Outcome significantly affected by exposure | No information about CI or p-value was given | +/- | +/- | + |

| Alamgir et al. (2022) [25] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Outcome affected by exposure | Some of the results were statistically insignificant, and varying degrees of precision were observed | + | + | + |

| Alamgir et al. (2022) [26] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Outcome affected by exposure in some cases | Moderate degree of precision indicated by an acceptable confidence interval | + | + | + |

| Alamgir et al. (2021) [27] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Outcome affected by exposure | High degree of precision indicated by a low confidence interval | + | + | + |

| Reference | Introduction | Methods | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were the Aims/ Objectives of the Study Clear? | Was the Study Design Appropriate for the Stated Aim(s)? | Was the Sample Size Justified? | Was the Target/ Reference Population Clearly Defined? (Is It Clear Who the Research Was about?) | Was the Sample Frame Taken from an Appropriate Population Base So That It Closely Represented the Target/ Reference Population under Investigation? | Was the Selection Process Likely to Select Subjects/ Participants that Were Representative of the Target/ Reference Population under Investigation? | Were Measures Undertaken to Address and Categorise Non-Responders? | Were the Risk Factor and Outcome Variables Measured Appropriate to the Aims of the Study? | Were the Risk Factor and Outcome Variables Measured Correctly Using Instruments/ Measurements That Had Been Trialled, Piloted, or Published Previously? | Is It Clear What Was Used to Determine Statistical Significance and/or Precision Estimates? (e.g., p-Values and Confidence Intervals) | Were the Methods (Including Statistical Methods) Sufficiently Described to Enable Them to Be Repeated? | |

| Yasin et al. (2022) [13] | + | + | - | + | - | - | NA | + | + | + | + |

| Naqvi et al. (2020) [28] | + | + | - | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + | + |

| Mohiuddin et al. (2016) [29] | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Reference | Results | Discussion | Others | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were the Basic Data Adequately Described? | Does the Response Rate Raise Concerns about Non-Response Bias? | If Appropriate, Was Information about Non-Responders Described? | Were the Results Internally Consistent? | Were the Results Presented for All the Analyses Described in the Methods? | Were the Authors’ Discussions and Conclusions Justified by the Results? | Were the Limitations of the Study Discussed? | Were There Any Funding Sources or Conflicts of Interest that May Affect the Authors’ Interpretation of the Results? | Was Ethical Approval or Consent of Participants Attained? | |

| Yasin et al. (2022) [13] | + | NA | NA | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Naqvi et al. (2020) [28] | + | N/A | NA | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Mohiuddin et al. (2016) [29] | + | N/A | N/A | + | + | + | + | - | +/- |

| Were the Criteria for Inclusion in the Sample Clearly Defined? | Were the Study Subjects and the Setting Described in Detail? | Was the Exposure Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | Were Objective and Standard Criteria Used for Measurement of the Condition? | Were Confounding Factors Identified? | Were Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated? | Were the Outcomes Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alamgir et al. (2016) [30] | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Baig et al. (2012) [31] | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

| Junaid et al. (2019) [32] | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + |

3. Results

3.1. Main Features of Studies Included

3.2. Designs of Included Studies

3.2.1. Use of Smokeless Tobacco Products Is the Most Important Contributing Factor

3.2.2. The Role of Smoking

3.2.3. Genetic Predisposition to Developing OC

3.2.4. HPV Contributes to the OC Burden

3.2.5. The Role of Socioeconomic and Cultural Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.1.1. Strengths

4.1.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sankaranarayanan, R.; Ramadas, K.; Amarasinghe, H.; Subramanian, S.; Johnson, N. Oral Cancer: Prevention, Early Detection. Disease Control Priorities. Cancer 2015, 3, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2018.

- Shrestha, A.D.; Vedsted, P.; Kallestrup, P.; Neupane, D. Prevalence and incidence of oral cancer in low-and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 29, e13207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Shang, Z. Burden of oral cancer in Asia from 1990 to 2019: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G.; Shah, S.; Hanif, M.; Asghar, A.; Shafique, M.; Ashraf, K. Cancer prevalence, incidence and mortality rates in Pakistan in 2018. Bull. Cancer 2020, 107, 517–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bile, K.M.; Shaikh, J.A.; Afridi, H.U.; Khan, Y. Smokeless tobacco use in Pakistan and its association with oropharyngeal cancer. EMHJ-East. Mediterr. Health J. 2020, 16, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, S.Z.; Nawaz, H.; Sepah, Y.J.; Pabaney, A.H.; Ilyas, M.; Ghaffar, S. Use of smokeless tobacco among groups of Pakistani medical students–a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grce, M.; Mravak-Stipetić, M. Human papillomavirus–associated diseases. Clin. Dermatol. 2014, 32, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, N.; Pervez, S.; Chundriger, Q.; Awan, S.; Moatter, T.; Ali, T.S. Oral cancer: Clinicopathological features and associated risk factors in a high risk population presenting to a major tertiary care center in Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakiullah, Z.; Ahmadullah, A.; Khisroon, M.; Saeed, M.; Khan, A.; Khuda, F.; Ali, S.; Javed, N.; Ovais, M.; Masood, N.; et al. Genetic susceptibility to oral cancer due to combined effects of GSTT1, GSTM1 and CYP1A1 gene variants in tobacco addicted patients of Pashtun ethnicity of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare. York Publ. Serv. 2009. Available online: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Aqeel, R.; Aslam, Z.; Amjad, A.; Anwar, A.; Asghar, F.; Tayyab, T.F. Examine the Prevalence of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma also Determine the Risk Factors and Causes of Improper Diagnosis. PJMHS 2019, 13, 833–835. [Google Scholar]

- Yasin, M.M.; Abbas, Z.; Hafeez, A. Correlation of histopathological patterns of OSCC patients with tumor site and habits. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugheri, M.H.; Channa, N.A.; Amur, S.A.; Khuhro, Q.; Soomro, N.A.; Paras, M.; Tunio, A.A. Risk factors for oral cancer disease in Hyderabad and adjoining areas of Sindh, Pakistan. Rawal Med. J. 2018, 43, 606–610. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, K.H.; Hussain, Q.A.; Patil, S.; Maralingannavar, M. Assessing the risk of Oral Cancer associated with Gutka and other smokeless tobacco products: A case–control study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2016, 17, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, N.; Kayani, M.A.; Malik, F.A.; Mahjabeen, I.; Baig, R.M.; Faryal, R. Genetic variation in carcinogen metabolizing genes associated with oral cancer in Pakistani population. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2011, 12, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baig, S.; Zaman, U.; Lucky, M.H. Human papilloma virus 16/18: Fabricator of trouble in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 69, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, S.; Mulla, M.; Mulla, M.; Tanveer, R.; Sabir, M.; Sultan, A.; Malik, S.A. Human papillomavirus, tobacco, and poor oral hygiene can act synergetically, modulate the expression of the nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathway for the development and progression of head and neck cancer in the Pakistani population. Chin. Med. J. 2022, 135, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Dreger, S.; Shah, S.M.; Pohlabeln, H.; Khan, S.; Ullah, Z.; Rehman, B.; Zeeb, H. Oral cancer via the bargain bin: The risk of oral cancer associated with a smokeless tobacco product (Naswar). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, A.; Husain, S.S.; Hosain, M.; Fikree, F.F.; Pitiphat, W.; Siddiqui, A.R.; Hayder, S.J.; Haider, S.M.; Ikram, M.; Chuang, S.K.; et al. Paan without tobacco: An independent risk factor for oral cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2000, 86, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, N.; Iqbal, A.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Shoaib, M.; Musharraf, S.G. Plasma metabolite profiling and chemometric analyses of tobacco snuff dippers and patients with oral cancer: Relationship between metabolic signatures. Head. Neck 2019, 41, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, N.; Sohail, M.; Ahmad, F.; Fareeha, S.; Jamil, S.; Mughal, N.; Salam, H. Risk factors of Oral cancer-A hospital based case control study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2018, 10, e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.Z.; Farooq, A.; Masood, M.; Shahid, A.; Khan, I.U.; Nisar, H.; Fatima, I. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of oral cavity cancer. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, R.F.; Sheikh, F.; Khan, R.; Fawad, B.; Haq, A.U. Survivin Promoter Polymorphism (−31 C/G): A genetic risk factor for oral cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2019, 20, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgir, M.M.; Jamal, Q.; Mirza, T. Gene-gene and gene-environment interaction: An important predictor of oral cancer among smokeless tobacco users in Karachi. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2022, 72, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgir, M.M.; Jamal, Q.; Mirza, T. Genetic profiles of different ethnicities living in Karachi as regards to tobacco-metabolising enzyme systems and the risk of oral cancer. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2022, 72, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Alamgir, M.M.; Shaikh, F. Life-time tobacco consumption and oral cancer among citizens of a high incidence metropolis. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2021, 71, 1588–1591. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, S.U.; Khan, S.; Ahmed, A.; Lail, A.; Gul, S.; Ahmed, S. Prevalence of EBV, CMV, and HPV in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients in the Pakistani population. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 3880–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, S.; Fatima, N.; Hosein, S.; Hosein, M. High risk of malignant transformation of oral submucous fibrosis in Pakistani females: A potential national disaster. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2016, 66, 1362–1366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alamgir, M.M.; Jamal, Q.; Mirza, T. Conventional clinical and prognostic variables in 150 oral squamous cell carcinoma cases from the indigenous population of Karachi. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 32, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baig, S.; Lucky, M.H.; Qamar, A.; Ahmad, F.; Khan, S.; Ahmed, W.; Chughtai, T.; Hassan, W.; Hussain, B.A.; Khan, A. Human papilloma virus and oral lesions in gutka eating subjects in Karachi. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2012, 22, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Junaid, M.; Khan, M.A.; Umair, M.; Nabi, A.; Khawar, A. Involvement of Oral Cavity Subsites And Etiological Factors for Oral Cavity Carcinoma In A Tertiary Care Hospital. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 27, 273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Pandey, U.; Bala, N.; Tewar, V.; Oanh, K.T. Tobacco habit in northern India. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 2006, 104, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Mbulo, L.; Twentyman, E.; Palipudi, K.; King, B.A. Disparities in smokeless tobacco use in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan: Findings from the global adult tobacco survey, 2014–2017. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.S.; Alaoui, O.M.; Najeh, H.S.; Benyahya, I. Human Papillomavirus and Oral Cancer: Systematic Review. J. Med. Surg. Res. 2019, 5, 599–610. [Google Scholar]

- Muwonge, R.; Ramadas, K.; Sankila, R.; Thara, S.; Thomas, G.; Vinoda, J.; Sankaranarayanan, R. Role of tobacco smoking, chewing and alcohol drinking in the risk of oral cancer in Trivandrum, India: A nested case-control design using incident cancer cases. Oral Oncol. 2008, 44, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Malik, D. Assessing the knowledge, attitude, and practices of cigarette smokers and use of alternative nicotine delivery systems in Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. Adv. Public Health 2021, 2021, 5555190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Nanavati, R.; Modi, T.G.; Dobariya, C. Oral cancer: Etiology and risk factors: A review. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2016, 12, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P—Population | Individuals 18 years of age or older suffering from malignancy of the lip or oral cavity, residing in Pakistan. |

| E—Exposure | The various risk factors or predisposing factors of cancer of the oral cavity or lip. |

| C—Comparison | No specific comparison needed for risk factor analysis. |

| O—Outcome | Identification and understanding of risk factors associated with oral cancer in Pakistan |

| S—Study Design | Peer-reviewed reports of observational studies and clinical trials will be included in this study. |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Individuals 18 years of age or older suffering from malignancy of the lip or oral cavity, residing in Pakistan. | Individuals younger than 18, patients suffering from head and neck cancers other than oral cancers. |

| Exposure | The various risk factors or predisposing factors for cancer of the oral cavity or lip. | Individuals who use known carcinogen-containing products but do not suffer from oral cancer were excluded. |

| Comparison | No specific comparison group needed. | |

| Outcome | Identification and understanding of risk factors associated with oral cancer in Pakistan. | Studies that do not contribute to the identification and understanding of risk factors associated with OC were excluded. |

| Study Design | Peer-reviewed reports of observational studies and clinical trials published in English language were included in this study. | Any secondary studies were excluded from this study. Any studies not published in English language were excluded. |

| Reference | Study Design and Methods | Context | Sample Size | Is Aim Specific to Risk Factors for OC? | Aim of the Study | Key Findings Regarding Risk Factors for OC | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awan et al. (2016) [15] | Case–control study | Karachi, Pakistan | 268 | Yes | To evaluate the risk of oral cancer associated with gutka and other ST products. | Gutka most used product leading to 1/3rd of cases. Chewing tobacco was 5.32 times higher compared to controls. | Controls may not disclose information about tobacco-chewing habits. |

| Alamgir et al. (2022) [25] | Cross-sectional case–control study | Karachi, Pakistan | 238 | Yes | Discover the role played by molecular mechanisms in OSCC carcinogenesis in the target population. | High risk of OSCC with the presence of combined gene polymorphisms of phase 1 and phase 2 enzymes. | Lack of representation of certain categories of tobacco consumption. |

| Alamgir et al. (2022) [26] | Cross-sectional, case–control study | Karachi, Pakistan | 358 | No | To evaluate intra-ethnic variability of CYP1A1-Mspl, GSTM1-Null, and GSTT1-null metabolic gene polymorphisms. | CYP1A1 Mspl m1/m2 and m2/m2 polymorphisms found in 85.7% of OSCC cases. | Too few members of Pushto-speaking community. Lack of representation of certain genotypes. |

| Zakiullah et al. (2015) [10] | Case–control study | Khyber Pukhtoonkhwa, Pakistan | 351 | Yes | To evaluate the potential role of CYP1AQ, GSTM1, and GSTT1 gene polymorphisms in the susceptibility to OC in the Pashtun Population of KPK. | Null genotypes of both GST genes with almost 3-fold higher risk of OC compared to wild type. | Since the subjects of the study were limited to the Pashtun population, findings may not be generalizable. Less controls as opposed to cases. |

| Alamgir et al. (2016) [30] | Retrospective observational study | Karachi, Pakistan. | 150 | Yes | Analysis of tumour characteristics and their association with common risk factors. | Habit of tobacco chewing found in approximately 78% of cases. | Dependent on the quality and accuracy of historical medical records. |

| Masood et al. (2011) [16] | Case–control study | Islamabad, Pakistan | 378 | Yes | Genetic changes in CYP1A1, GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 genes and their association with risk of OC. | Significantly higher proportion of OC patients had GSTM1 deletion genotype as opposed to controls. | Matching of controls by age and sex might not eliminate all potential confounding factors such as smoking, diet, etc. |

| Mohiuddin et al. (2016) [29] | Multi-centre cross-sectional study | Karachi, Pakistan | 1774 | Yes | To determine the relationship between age, gender, and other associated risk factors linked with the malignant transformation of OSMF into OSCC. | Females included in the study showed higher malignant transformation than males. | Uses non-probability convenience sampling to select participants which may cause sampling bias. |

| Zil-E-Rubab et al. (2018) [17] | Case–control study | Karachi, Pakistan | 300 | Yes | To find out the association between HPV 16/18 genotypes in Pakistan patients with OSCC. | Pts infected with HPV 16/18 had significantly higher chances of developing OSCC as opposed to patients who did not have high-risk strains. | Only 100 cases as opposed to 200 controls. |

| Baig et al. (2012) [31] | Descriptive study | Karachi, Pakistan | 262 | No | To determine the frequency of HPV in eaters of Gurka presenting with oral lesions. | Significantly higher frequency of high-risk HPV strains in subjects who have been chewing tobacco for over 10 years. | Most of the participants were male; this was a single-centre study, limiting generalizability. |

| Sarwar et al. (2022) [18] | Cross-sectional study | Different hospitals of Pakistan in Islamabad and KPK. | 152 | No | To detect high-risk genotypes of HPV and protein expression of NF-κB signalling pathway in HNC patients with HPV infection. | Strong association between HR-HPV infection and oral cavity cancer patients | Cross-sectional design unable to inform causality. |

| Junaid et al. (2019) [32] | Descriptive retrospective study | Islamabad, Pakistan | 200 | No | To determine the frequency of carcinoma of various oral cavity subsites along with risk factors like smoking. | Tobacco-smoking found to be the major risk factor for a higher frequency of oral cancer. No such association was found for age and gender. | Retrospective design inherently prone to some degree of recording problems, which could skew the data in one way or another, making the findings less reliable. |

| Alamgir & Shaikh. (2021) [27] | Cross-sectional case–control study | Karachi, Pakistan | 358 | No | To find out the level of exposure of oral mucosa to tobacco products in terms of lifetime tobacco indices. | 83.4% of the patients suffering from OC were found to be tobacco users in one way or another. | Non-availability of histopathology slides for oral pre-cancerous lesions. |

| Khan et al. (2017) [19] | Multi-centre case–control study | Khyber-Pukhtoonkhwa, Pakistan | 258 | Yes | Assess the association between naswar and the risk of OC. | Ever and current users of naswar had a 20-fold higher risk of oral cancer as opposed to non-users. | Study sample, particularly hospital controls, may not be representative of the general population of KPK. |

| Merchant et al. (2000) [20] | Case–control study | Karachi, Pakistan | 228 | Yes | To clarify the independent association between paan and oral cancer. | People using paan w/o tobacco were 9.9 times more likely to develop OC, and people using paan with tobacco were 8.4 times more likely to develop OC. | Few cases compared to controls, plus some degree of recall bias. |

| Shahid et al. (2018) [21] | Case–control | Karachi, Pakistan | 234 | No | To obtain and compare comprehensive metabolic profiles of plasma samples of pure tobacco snuff dippers with oral cancer. | Strong correlation between regular tobacco snuff dippers and oral cancer. | - |

| Naqvi et al. (2020) [28] | Cross-sectional study | Karachi, Pakistan | 58 | Yes | To find out frequencies of EBV, CMV, and HPV infection among patients with OSCC in the Pakistani population. | All cases negative for HPV; CMV detected in 5 percent of cases and 25.86% of cases were positive for EBV. | Very small sample size. |

| Mugheri et al. (2018) [14] | Case–control study | Hyderabad and adjoining areas of Sindh | 662 | Yes | To estimate the association of various epidemiological risk factors for oral cancer. | Alcohol, cigarette smoking, use of khula ghee and pakwan, Manipuri, and collective addictions are significant risks for oral cancer. | Recall bias i.e., patients with oral cancer are more likely to mention causative factors than controls. |

| Azhar et al. (2018) [22] | Case–control study | Karachi, Pakistan | 124 | Yes | To ascertain prevalent risk factors for OC in the Pakistani population. | Smokeless tobacco found to be an independent risk factor for oral cancer. | Small sample size + recall bias. |

| Khan et al. (2020) [23] | Case–control study | Lahore, Pakistan | 210 | Yes | To evaluate the risk of oral cavity cancer with the use of various smokeless tobacco products. | Positive association between ever users of smokeless tobacco and risk of OC | Less proportion of female patients and most of the patients were derived from one hospital which indicates limited generalizability. |

| Mehdi et al. (2019) [24] | Case–control study | Hospital-setting, Karachi, Pakistan | 148 | Yes | To find an association between survivin polymorphism and the prevalence of OSCC in a subset of the Pakistani population. | Significant association between CC and GG genotypes of survivin and OSCC prevalence. | Too few cases in the sample and hospital settings indicate little generalizability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, M.F.; Hayhoe, R.P.; Kabir, R. Exploring the Risk Factors for Oral Cancer in Pakistan: A Systematic Literature Review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12020025

Khan MF, Hayhoe RP, Kabir R. Exploring the Risk Factors for Oral Cancer in Pakistan: A Systematic Literature Review. Dentistry Journal. 2024; 12(2):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12020025

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Muhammad Feroz, Richard P. Hayhoe, and Russell Kabir. 2024. "Exploring the Risk Factors for Oral Cancer in Pakistan: A Systematic Literature Review" Dentistry Journal 12, no. 2: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12020025

APA StyleKhan, M. F., Hayhoe, R. P., & Kabir, R. (2024). Exploring the Risk Factors for Oral Cancer in Pakistan: A Systematic Literature Review. Dentistry Journal, 12(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj12020025