3.2.1. Urban Versus Rural Consumers

Worldwide, the urban population is greater than the rural population. In 1950, 30% of the population was urban; in 2014, that value was 54%, and, by 2050, a 66% urban population is projected [

19]. In Argentina, as a result of an urbanization process, the rural population decreased rapidly during the twentieth century. In 1999, 13% of the population lived in cities with fewer than 2000 inhabitants (rural population), whereas, by 2010, this percentage decreased to 9% [

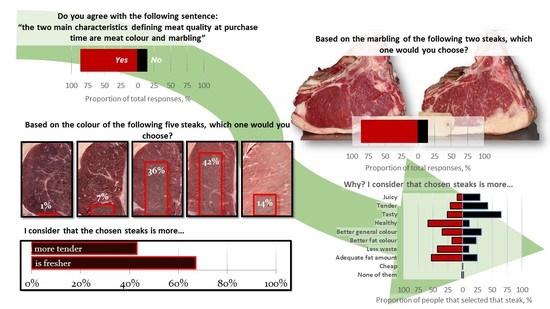

15]. Urban life is associated with higher literacy and education levels, access to better health systems, and better political/cultural opportunities. However, in the present study, only the frequency of the “fresh” criterion in the question comparing 5 steaks based on color (

Table 3; Picture 1) was affected by the place of residence. The percentage of people who chose that criterion for selecting one steak or another was 60%, instead of the expected 56%. Therefore, we can consider it to be a spurious result and dismiss it. In conclusion, regardless of whether the respondents lived in a rural or urban area, they showed similar purchase and consumption habits, beliefs, and choice behavior. Similarly, Zapata et al. [

11] found only a slight difference in overall meat consumption between urban and rural consumers; however, they found major differences in the consumption of meat from different animal species, indicating that probably, consumers have a behavior pattern based on which livestock predominates in the region where they live.

3.2.2. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

The present study shows that socio-demographic characteristics influence purchase habits and beliefs, in addition to their effects on the perception of color and marbling.

In general, no differences between socio-demographic characteristics were found between regions for any of the answers, except for occupation (

Figure 1). Contrary to the Pampeana region, there are more beef producers and fewer crop producers in the CABA-GBA region than expected. Regarding the criteria used for beef choice, differences between regions were only detected for Picture 3: “juiciness” was chosen more often than expected in the CABA-GBA region (26% instead of 19%) whereas ”better general color” was chosen less often than expected in the northwest region (3% instead of 4%). This result could be related to different animal breeds farmed in the different regions, which produce different beef qualities. Angus and Hereford are the main breeds that supply the beef market in the CABA-GBA region, whereas Criollo, Bradford and Brangus are the main breeds farmed in the northwest region. As for Hypothesis 1, these findings were considered spurious, without practical relevance. In conclusion, consumer perception of color and marbling is not dependent on the region where the respondents live.

Education level did not influence purchase habits, beliefs, or choice behavior, but consumer occupation influenced the frequency of beef consumption and choice behavior. Gender only affected the belief question; 87% of men agreed with the idea that color and marbling are the main attributes at purchase time, whereas 92.2% of women agreed with that statement. Several studies [

20,

21,

22] reported differences between men and women in terms of meat consumer perception. For instance, modern Italian consumers are worried about animal welfare, with women more sensitive to it; they perceive this attribute more strongly than men do as indicative of meat quality [

23]. Similar results were found by Schnettler et al. [

24] in the Chilean population: women had different animal welfare expectations and they wanted more information about animal welfare than men.

Concerning consumer age, differences found in purchase habits and in choice behavior are represented in

Figure 1. The youngest consumers (≤35 years old) were in charge of buying beef less frequently than expected, whereas the contrary happened for people 36–55 years old. However, the three criteria that were affected by age were only chosen by people >55 years old (

Figure 2;

Table 4).

Since choice behavior and belief depended on gender, age and occupation, and purchase habits depended on age, hypothesis 2 should not be rejected.

As consumer gender, age and occupation influenced purchase habits and choice behavior, they can be considered as a consumer clustering.

3.2.3. Purchase Habits and Belief

Being or not being the person in charge of buying beef in the household did not influence the consumer’s choice behavior but did influence their beliefs (

Table 5). People in charge of buying the beef agreed with the sentence about color and marbling slightly more frequently than expected (90.7% vs. 89.9%), whereas the agreement was slightly less frequent than expected (86.6% vs. 89.9%) for people not in charge of buying the meat. Nevertheless, most people, independently of being in charge or not in charge, agreed with the idea that color and marbling are relevant at purchase time (

Table 5), supporting the conclusions of Bifaretti [

2]. Many other studies have demonstrated that consumers use a visual appraisal to infer sensory quality [

25,

26,

27,

28].

Beef consumption frequency affected the choice and some of the criteria used to select options of Picture 1 and Picture 2 (

Table 5). In addition, differences were found for the question about the importance of color and marbling at the moment of purchase. Only 75% of the people eating beef once a month agreed with the sentence, whereas the main average was 87%. The previous experience with the product and the frequency of consumption as factors influencing consumer perception of a certain food product were already stated by several authors [

25,

29,

30].

The degree of agreement with the sentence about color and marbling importance influenced the choice of Picture 1 as well as some criteria used in the choices of Picture 2 and Picture 3. Surprisingly, an “adequate fat amount” of the rib was marked as important more frequently for people in disagreement with the sentence (56%) than for the people in agreement with it (48%), and “better general color” was not affected by the belief about the importance of color and marbling.

3.2.4. Decision Trees for Choices on Pictures as a Function of Significant Socio-Demographic Variables, Purchase Habits and Beliefs

It is well known that both the place of residence and socio-economic context have an influence on choice and pattern behavior [

31]. Moreover, ethics, religious beliefs and traditions influence beef consumption [

32]. In addition, consumer perception can be influenced by attitudes and beliefs about the characteristics of certain products and the way they are produced, handled, or distributed.

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, respectively, show the decision trees for the choices of Pictures 1, 2, and 3 as a function of the socio-demographic variables, purchase habits, and beliefs that were significant (that is, gender, age, activity, place of purchase, frequency of beef consumption, and belief about color and marbling importance), as well as on the criteria used for choosing each of the pictures.

For Picture 1, 100% of the respondents were correctly forecasted as selecting option 4 of the picture and their occupation, and freshness seemed to be the most important criterion (

Figure 3). It is well known [

16,

17,

33] that at the point of purchase, the color of fresh beef is one of the most important characteristics to the consumer.

The tree for Picture 2 (

Figure 4) correctly classified 100% of the respondents in option 2 (less marbling). The percentage of the respondents selecting option 2 was higher when their occupation was related to human health (node 3, 95.4%). In this sense, the fact that consumers chose a lean option is in accordance with the recommendation of the World Health Organization [

34]. Node 2 grouped people who work on occupations related to meat production or commercialization and separated them into two nodes as a function of their beliefs. People who agreed with the importance of color and marbling (node 4, 81.7%) chose option 2 of the pictures more often than did people in disagreement with it (node 5, 66.7%). In this sense, marbling is considered an important beef quality trait throughout the world because it is associated with a positive eating experience [

35], but, contrary to what is thought, most workers in the beef industry chose the lean option. Finally, node 4 was divided into two groups based on their beef consumption frequency. At a higher frequency of consumption, a lower percentage of people chose option 2 of Picture 2.

In the tree for Picture 3 (

Figure 5), 89.3% of the answers were correctly forecasted. Eighty-seven percent of the respondents chose rib 1 (less fat). This percentage raised to 97% in node 1, which comprised people who chose “healthy” as a criterion to select the less fattened rib. This node 1 was divided into two as a function of the fat color criterion. People who did not mark the “fat color” criterion (node 3) were divided according to the “less waste” criterion. Node 4 was also divided into two as a function of the “adequate marbling” criterion. On the other side, node 2 represented people that did not mark the “healthy” criterion as important. In this node, rib 1 was chosen less frequently than in node 1 (76%). Node 2 was divided into two as a function of the

tasty criterion. If “tasty” was unmarked (node 6), rib 1 was chosen by 88% of the respondents, whereas, if “tasty” was marked as important (node 5), only 52% chose rib 1. Node 5 was divided into two groups depending on the “less waste” criterion; people marking it as important chose rib 1 (node 12), whereas people who did not mark it (node 11) chose rib 2. It is the only node in which rib 2 was more frequently chosen than rib 1. Finally, node 6 was divided into two depending on “adequate marbling”; rib 1 was more frequently selected when the marbling criterion was marked (node 14) than when it was unmarked (node 13). In general terms, the highest frequency of the choice of rib 1 was in node 8 (“healthy”, “less waste”, “fat color” not important) and the highest frequency of choice of rib 2 was in node 11 (“tasty”, “healthy” not important, “less waste” not important).

Clearly, there are two target markets in Argentina based on beef fat levels: one for people who are interested in their health and want lean beef with an adequate color, and another market for people who want palatability. Respondents associated the degree of marbling with “juicy”, “healthy”, and “tasty” criteria. They associated the less fattened rib with “healthy and adequate amount of fat”. Differences in fat preferences have been found between geographical regions [

36]; for instance, slightly visible fat in beef (including cover fat and intramuscular fat) was preferred in some countries such as Spain [

37,

38].

3.2.5. Multiple Factor Analysis

Table 6 shows the percentage of variability explained by the two first factors for each of the multiple factor analyses (MAF) carried out, as well as the cosine squared for each variable in each factor.

In the MAF of Picture 1, the first two factors explained 41.9% of the variability. “Tender”, “tasty” and “juicy” criteria presented a sum of cosine squared > 0.4 and were therefore selected for the hierarchical cluster. In the MAF of Picture 2, 68% of the variability was explained by the first two factors and the selected criteria were “tender”, “tasty”, “juicy” and “healthy”. In the MAF of Picture 3, 36.1% of the variability was explained by the first two factors and selected criteria were “tender”, “tasty”, “juicy”, “fat color”, and “general color”.

Three groups of consumers were obtained from the cluster analysis, with a cophenetic correlation of 0.456. The description of consumer profiles (clusters) according to their socio-demographic variables, purchase habits and beliefs, and by their choice behavior, are shown in

Table 7;

Table 8 respectively.

No differences between groups were found for consumer gender, consumer age, or beef consumption frequency (p > 0.05), but occupation differed between consumer groups (p < 0.001). In the same way, no differences were found between groups in the chosen Picture 1 or chosen Picture 2 categories (p > 0.05), but differences were found for the chosen Picture 3 category (p < 0.001) between the three different groups.

The first cluster (

n = 751, 38.3% of the sample) comprises respondents who showed a profile that could be termed as “hedonic”. To choose the pictures, they used the criteria “tender”, “tasty” and “juicy”, whereas “healthy” or “color” was less frequently chosen than expected. A greater proportion of them preferred the second option of Picture 3; that is, the most fattened. According to Smith and Carpenter [

39], tenderness, flavor, and juiciness are the primary traits to describe overall beef palatability. Moreover, according to Lusk et al. [

40], these primary traits are highly correlated with overall experienced quality, intention to purchase, and willingness to pay. Thus, this group is characterized by choosing based on palatability. In this group, we found the most people whose occupation was related to crop production (33.8%). The second group (n = 734, 37.4% of the sample) selected the criterion “healthy” in Picture 2 and in Picture 3, but they did not mark any of the other criteria as important and they cannot be defined in terms of occupation. Thus, they could be classified as “health-conscious”. They chose the less fattened Picture 3 as recommended by the WHO [

34] to decrease the number of calories in their meals. The third group (

n = 475, 24.2%) chose “fresh” and “healthy” for Picture 1, no particular criteria for Picture 2 and “less waste”, “better fat color”, and “better general color” for Picture 3; that is, they were people that use general appearance to choose the pictures. Visual appearance characteristics are highly related to consumer expectations and are intrinsic quality cues [

17]. Moreover, because these characteristics are used to access food quality, they are highly related to their choice at purchase [

41]. Consumers from the third group were not worried about tenderness, juiciness, taste, or health, although, curiously, they were mostly occupied in human health-related jobs. Although clusters could not be defined in terms of consumers’ age, people in the “appearance” group tended to be the youngest (≤35 years old); this could explain their lack of concern with the “healthy” criterion.

Consumers are the last link of the production chain, and they have their own expectations about the product, associated with their beliefs and/or feelings. According to Deliza et al. [

42], previous information and experiences form the expectation process. In this sense, the frequency of consumption influences the expectation process; indeed, it influences the perception of beef quality, as shown in the present study. Since there is little information about fresh meat, consumers have difficulties in forming their quality expectations. According to Grunert et al. [

43], labeling and appearance are the main characteristics that form meat quality expectations. However, they do not seem to be very good predictors of meat-eating quality.

The three groups of consumers identified in Argentina are important for marketing strategies, as they have their own characteristics. While consumers in the “hedonic” group search for a pleasurable sensory experience, consumers in the “appearance” group search for visual aspects, and those in the “health-conscious” group are interested in a healthy diet.