Barriers towards Resilient Performance among Public Critical Infrastructure Organizations: The Refugee Influx Case of 2015 in Sweden

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework—Resilience as Adaptive Capacity

3. Methodology

3.1. Respondent Selection

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

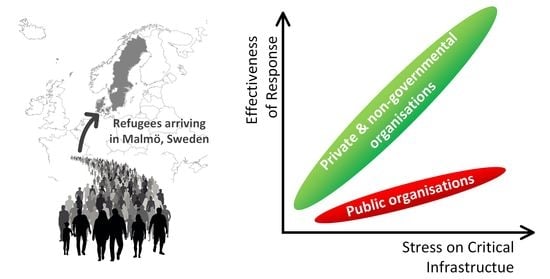

4. The Increased Refugee Influx in Sweden 2015—Event Description, Organization Involvement and Organizational Preconditions

4.1. Early Response at Malmö Central Station

“according to [the security guards] there started to arrive a massive amount of people with Syrian origin. We had heard on the news that people travelled by foot through Europe and then Denmark, but at the time we did not know if they wanted to seek asylum in Denmark, but it turned out that most of them had Sweden as the final destination, so it quickly became quite hectic. On the first day we had several hundreds who came to Malmö station and did not know where to go. No authority was represented because everyone was taken by surprise”

“it was good that [the NGOs] came to help at the station, but it also fueled the chaos a bit, because there were a lot of civilians who probably had a good agenda, but who sometimes did things the wrong way. There were no leadership, instead 100 individualists who pulled in different directions […], they put up tables and handwritten signs in the middle of the pedestrian flow. We had to control that in some way, and that’s how it all started”

“our governmental authority mission is not to find people and ask them if they want to seek asylum in Sweden. If law and order are at risk, it becomes the Police’s responsibility. This was a big question at the beginning of the autumn where people didn’t know our mission, which led to false rumors spreading at Malmö central station”

4.2. Public Responsible Organizations’ Response

“I don’t think anyone could grasp how severe it really was. You could get a call at night saying that another accommodation has 130 kids in line, they have no place for them and neither did we. Then we had to have different strategies, ok, should social services arrange a bus for the time being, do we have something for them to eat, can they stay warm, until we found a place for them to stay. But it went well, I still think. Somehow, in some sick way, we succeeded. But it was also work around the clock”

“I think it would have been better if they had said ’Ok, now we have this situation, we, therefore, have to break this rule, but we try to meet the intention of the rule by doing like this instead‘. Then everyone would have been aware of the need to change and the compensating measures”

“we had quite a lot of [routines] and we could scale them up. But then we had to do simplified procedures to handle the large amount. […] We had to do new routines and that routine could be changed from one day to another because we had to make it as easy as possible. So yes, we followed our routines but they had to be changed and I think that if we had not had the routines it would have been even more difficult to handle a situation like this. […] Then, of course, we failed to do some things when it went at such a high speed for such a long time. And that is why it is important to have these routines in place so you know a little about where you are”

4.3. Organizational Preconditions and Relationships

“in other organizations, they must present for and ask the management level for permission […], but here it does not work that way, if I think something is reasonable I can just make a decision and say “yes, let’s do that”, and tell my management after the decision is made, which I think makes us more dynamic. But I need to be clear—we are not a public authority, we are owned by the government, but we are not an authority”

“this was nothing that stood out for us, a storm could come tomorrow or a severe accident next week that takes more effort than this. […] When it comes to technical supervision and traffic control, stuff happens. It’s their job”

“we experienced that […] there was simply one process at central crisis management and another process here […] and they didn’t match, it could have been a closer collaboration. We probably sometimes experienced that the representatives [from the central crisis management team] did not have full insight in our work, so it was difficult perhaps for them to make helpful decisions […], it was never a real connection to our reality”

“The parliament has decided something, and therefore we execute it. It is not about what we think or feel about an issue, we follow the laws that exist. We don’t invent our own laws here. We are given a set of rules and based on that, we make decisions”

5. Analysis and Discussion

- Public organizational design as a barrier to resilient performance

- Public steering as a barrier to value responsiveness

5.1. Public Organizational Design as Barrier towards Resilient Performance

5.2. Public Steering Creates a Barrier towards Value Responsiveness

5.3. Future Resilience Engineering Research in the Public Sector

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Counsil, D. 114/EC of 8 December 2008 on the identification and designation of European critical infrastructures and the assessment of the need to improve their protection. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 23, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rød, B.; Lange, D.; Theocharidou, M.; Pursiainen, C. From Risk Management to Resilience Management in Critical Infrastructure. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaka, L.; Hernantes, J.; Sarriegi, J.M. A holistic framework for building critical infrastructure resilience. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 103, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.E. Resilience and disaster risk reduction: An etymological journey. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 2707–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petersen, L.; Lange, D.; Theocharidou, M. Who cares what it means? Practical reasons for using the word resilience with critical infrastructure operators. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 199, 106872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeler, D.G.; Allen, C.G. Quantifying Resilience. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milch, V.; Laumann, K. Interorganizational complexity and organizational accident risk: A literature review. Saf. Sci. 2016, 82, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, J.; Wears, R.L.; Hollnagel, E. (Eds.) Resilient Health Care, Volume 3: Reconciling Work-as-Imagined and Work-as-Done; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel, E.; Woods, D.D. Cognitive systems engineering: New wine in new bottles. Int. J. Man. Mach. Stud. 1983, 18, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrow, C. Normal Accidents: Living with High Risk Technologies; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, E. Cognition in the Wild; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, J. Risk management in a dynamic society: A modelling problem. Saf. Sci. 1997, 27, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N. A new accident model for engineering safer systems. Saf. Sci. 2004, 42, 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hollnagel, E.; Woods, D. Joint Cognitive Systems: Foundations of Cognitive Systems Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Patriarca, R.; Bergström, J.; Di Gravio, G.; Costantino, F. Resilience engineering: Current status of the research and future challenges. Saf. Sci. 2018, 102, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, D.J.; Woods, D.D.; Dekker, S.W.A.; Rae, A.J. Safety II professionals: How resilience engineering can transform safety practice. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 195, 106740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branlat, M.; Woltjer, R.; Save, L.; Cohen, O.; Herrera, I. Supporting resilience management through useful guidelines. In Proceedings of the 7th Resilience Engineering Association Symposium, Liège, Belgium, 26–29 June 2017; pp. 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, D.D. The theory of graceful extensibility: Basic rules that govern adaptive systems. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2018, 38, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux-Dufort, C. The devil lies in details! How crises build up within organizations. J. Conting Cris. Manag. 2009, 17, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Laere, J. Wandering Through Crisis and Everyday Organizing; Revealing the Subjective Nature of Interpretive, Temporal and Organizational Boundaries. J. Conting Cris. Manag. 2013, 21, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu Saurin, T.; Patriarca, R. A taxonomy of interactions in socio-technical systems: A functional perspective. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 82, 102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, D.D.; Hollnagel, E. Prologue: Resilience engineering concepts. In Resilience Engineering; Hollnagel, E., Woods, D.D., Leveson, N., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2006; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lay, E.; Branlat, M.; Woods, Z. A practitioner’s experiences operationalizing Resilience Engineering. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2015, 141, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costella, M.F.; Saurin, T.A.; de Macedo Guimarães, L.B. A method for assessing health and safety management systems from the resilience engineering perspective. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degerman, H.; Bram, S.; Eriksson, K. Resilient performance in response to the 2015 refugee influx in the Øresund region. In Safety and Reliability—Safe Societies in a Changing World; Haugen, S., Barros, A., van Gulijk, C., Kongsvik, T., Vinnem, J.E., Eds.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1313–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Bram, S.; Degerman, H.; Melkunaite, L.; Urth, T.; Carreira, E. Organisational Resilience Concepts Applied to Critical Infrastructure. Deliv. Number Table Contents 2016, 653390. [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel, E. Why is Work-as-Imagined Different from Work-as-Done? In Resilient Health Care; Wears, R.L., Hollnagel, E., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, S. Resilience engineering: Chronicling the emergence of confused consensus. In Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts; Hollnagel, E., Woods, D.D., Leveson, N., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 2006; pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Faverge, J.-M.; Ombredane, A. L’analyse du Travail: Facteur D’economie Humaine et de Productivite; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, D.D.; Johannesen, L.J.; Cook, R.I.; Sartor, N.B. Behind Human Error: Cognitive Systems, Computers, and Hindsight; Crew Systems Ergonomics Information Analysis Center: Columbus, OH, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Moppett, I.K.; Shorrock, S.T. Working out wrong-side blocks. Anaesthesia 2018, 73, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patriarca, R.; Falegnami, A.; Costantino, F.; Di Gravio, G.; De Nicola, A.; Villani, M.L. WAx: An integrated conceptual framework for the analysis of cyber-socio-technical systems. Saf. Sci. 2021, 136, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.; Meyer, A.; Eisenhardt, K.; Carley, K.; Pettigrew, A. Introduction to the Special Issue: Applications of Complexity Theory to Organization Science. Organ. Sci. 1999, 10, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKelvey, B. Complexity theory in organization science: Seizing the promise or becoming a fad? Emergence 1999, 1, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariès, J. Complexity, Emergence, Resilience…. In Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts; Hollnagel, E., Woods, D.D., Leveson, N., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 2006; pp. 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch disaster. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 628–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duit, A.; Galaz, V.; Eckerberg, K.; Ebbesson, J. Governance, complexity, and resilience. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, A. Bureaucratic values and resilience: An exploration of crisis management adaptation. Public Adm. 2014, 92, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, A.; Borys, D. Working to rule, or working safely. In Trapping Safety into Rules: How Desirable or Avoidable Is Proceduralization? Bieder, C., Bourrier, M., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Aldershot, UK, 2013; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Westrum, R. A typology of resilience situations. In Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts; Hollnagel, E., Woods, D., Leveson, N., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 2006; pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Frykmer, T.; Uhr, C.; Tehler, H. On collective improvisation in crisis management—A scoping study analysis. Saf. Sci. 2018, 110, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Managing the Unexpected: Sustained Performance in a Complex World; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grote, G. Uncertainty management at the core of system design. Annu. Rev. Control 2004, 28, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; ’t Hart, P. Organising for effective emergency management: Lessons from Research. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2010, 69, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boin, A. The new world of crises and crisis management: Implications for policymaking and research. Rev. Policy Res. 2009, 26, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, J.; Dahlström, N.; Van Winsen, R.; Lützhöft, M.; Dekker, S.; Nyce, J. Rule and role-retreat: An empirical study of procedures and resilience. J. Marit. Res. 2009, 6, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, S. Failure to adapt or adaptations that fail: Contrasting models on procedures and safety. Appl. Ergon. 2003, 34, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucks, I.; Dien, Y. ‘No rule, no use’? The effects of over-proceduralization. In Trapping Safety into Rules; Bieder, C., Bourrier, M., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 2013; pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, K.; Mcconnell, A. Contingency planning for crisis management: Recipe for success or political fantasy? Policy Soc. 2011, 30, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L. Mission Improbable: Using Fantasy Documents to Tame Disaster; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, A.; McConnell, A. Preparing for Critical Infrastructure Breakdowns. J. Conting. Cris. Manag. 2007, 15, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, D.D.; Dekker, S.; Cook, R.; Johannesen, L.; Sarter, N. Chapter 8: Goal Conflicts. In Behind Human Error; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 2010; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, D.D. Creating foresight: Lessons for enhancing resilience from Columbia. In Organization at the Limit: Lessons from the Columbia Disaster; Starbuck, W., Farjoun, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, J. The role of hierarchical knowledge representation in decision making and system management. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1985, SMC-15, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Danermark, B.; Ekström, M.; Karlsson, J.C. Explaining Society: Critical Realism in the Social Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell, A. Overview: Crisis management, influences, responses and evaluation. Parliam. Aff. 2003, 56, 363–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M. Beyond neopositivists, romantics, and localists: A reflexive approach to interviews in organizational research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOU 2017:12 Att ta Emot Människor på Flykt Sverige Hösten 2015. 2017. Available online: https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/e8c195d35dea4c05a1c952f9b0b45f38/hela-sou-2017_12_webb_2.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- RiR 2017:4 Lärdomar av Flyktingsituationen Hösten 2015—Beredskap Och Hantering. 2017. Available online: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/skrivelse/2017/06/skr.-201617206/ (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Alvesson, M.; Sköldberg, K. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rennstam, J.; Wästerfors, D. Analyze!: Crafting Your Data in Qualitative Research; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, J.N.; Cho, Y.; Lochmiller, C.R. Learning to Do Qualitative Data Analysis: A Starting Point. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2020, 19, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, D.D. The strategic agility gap: How organizations are slow and stale to adapt in turbulent worlds. In Human and Organisational Factors Practices and Strategies for a Changing World; Journé, B., Laroche, H., Bieder, C., Gilbert, C., Eds.; SpringerOpen: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, D.D.; Branlat, M. Basic Patterns in How Adaptive Systems Fail. In Resilience Engineering in Practice: A Guidebook; Hollnagel, E., Pariès, J., David, D., Woods, J.W., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Antonsen, S.; Almklov, P.; Fenstad, J. Reducing the Gap Between Procedures and Practice: Lessons from a sucessful safety intervention. Saf. Sci. Monit. 2008, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rae, A.J.; Provan, D.J.; Weber, D.E.; Dekker, S.W.A. Safety clutter: The accumulation and persistence of ‘safety’ work that does not contribute to operational safety. Policy Pract. Health Saf. 2018, 16, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, S. Just Culture: Balancing Safety and Accountability; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Catino, M. A review of literature: Individual blame vs. organizational function logics in accident analysis. J. Conting. Cris. Manag. 2008, 16, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, D.D.; Cook, R.I. Perspectives on human error: Hindsight Biases and Local Rationality. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, S. The Field Guide to Understanding ’Human Error’; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| RE Principle Theoretical Framework | Included RE Principles |

|---|---|

| Complexity as a prerequisite | Complex systems view [22] Not predicting the future based on scenarios from the past [22] Variability and uncertainty is inherent in complex work [23] Increasing organizational flexibility [24] |

| Systems perspective | Need for proactivity [22] A systems view is necessary to understand and manage complex work [23] Focus on what we want: to create safety [23] An expanded system awareness directed towards, for example, goal conflicts and trade-offs [24] A systems perspective [25,26] |

| The human contribution | Human being as success factor [22] Expert operators are sources of reliability [23] Humans as an adaptive success factor [25,26] |

| Understanding real work | It is necessary to understand “normal work” [23] Learning from both incidents and normal work and reducing the gap between management’s image of work and real operative work challenges [24] Recognizing the difference between work-as-imagined and work-as-done [25,26] |

| Interviewed Organization | Responsibility Connected to the Event |

|---|---|

| The Swedish Migration Agency | Swedish governmental agency responsible for the asylum process. In the acute phase responsible for housing and registration of adults and families. |

| Malmö municipality | A Swedish municipality, which has an overall responsibility for municipal services in the geographical area. In the acute phase responsible for housing and registration of unaccompanied children. |

| The Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency | A Swedish governmental agency with the general responsibility of helping the society to prepare for crisis. In this event they supported the Migration Agency with crisis management knowledge. |

| The Swedish Armed Forces | A governmental agency, which supported the Migration Agency’s crisis staff. |

| The Øresund Bridge Consortium | A Danish-Swedish private infrastructure operator responsible for maintenance, traffic control of road traffic and the toll stations of the bridge connection. Most refugees arrived in Malmö by train, and some by car, via the bridge. |

| Jernhusen | A governmentally owned but private infrastructure operator and manager of the train stations in Sweden. Most refugees arrived at Malmö central station, where Jernhusen made some of the first official observations, and later helped with the official arrangements. |

| The Swedish Red Cross | Established international aid agency. In Malmö they were represented in the official arrival hub at Posthusplatsen square outside Malmö central station. Some volunteers also helped on the accommodations. |

| Kontrapunkt | A local cultural association in Malmö. In the event they changed their focus and became an autonomous arrival center, housing and feeding several hundreds of refugees each night in their premises. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Degerman, H. Barriers towards Resilient Performance among Public Critical Infrastructure Organizations: The Refugee Influx Case of 2015 in Sweden. Infrastructures 2021, 6, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures6080106

Degerman H. Barriers towards Resilient Performance among Public Critical Infrastructure Organizations: The Refugee Influx Case of 2015 in Sweden. Infrastructures. 2021; 6(8):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures6080106

Chicago/Turabian StyleDegerman, Helene. 2021. "Barriers towards Resilient Performance among Public Critical Infrastructure Organizations: The Refugee Influx Case of 2015 in Sweden" Infrastructures 6, no. 8: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures6080106

APA StyleDegerman, H. (2021). Barriers towards Resilient Performance among Public Critical Infrastructure Organizations: The Refugee Influx Case of 2015 in Sweden. Infrastructures, 6(8), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures6080106