In Vivo Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi Activity of Hydro-Ethanolic Extract and Isolated Active Principles from Aristeguietia glutinosa and Mechanism of Action Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Proof of Concept

| Extract or Compound | Percentage of Lyses (%) a |

|---|---|

| WHEAP | 82 ± 5 |

| (1) | 91 ± 4 |

| (2) | 54 ± 7 |

| GV b | 90 ± 6 |

2.2. Accessing the Mechanism of Action

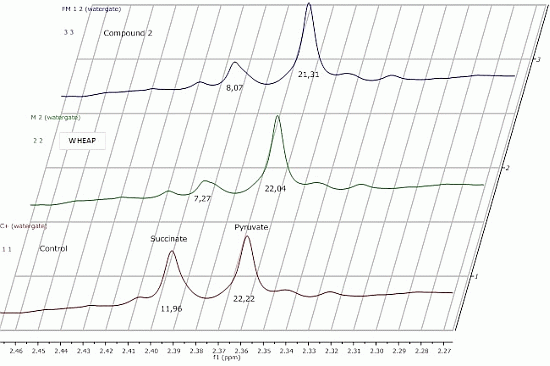

2.2.1. 1H-NMR Metabolomic Studies

| Compound a/Metabolite b | Gly | Succ | Pyr | Ace | Ala | Lac |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wheap | 2.96 ± 0.02 | 7.27 ± 0.09c | 22.04 ± 0.54 | 27.39 ± 0.67 | 24.78 ± 0.38 | 11.81 ± 0.01 |

| ( 1) | 3.07 ± 0.03 | 11.96 ± 0.52 | 23.87 ± 0.65 | 32.12 ± 0.83 | 27.13 ± 0.48 | 12.74 ± 0.19 |

| ( 2) | 2.71 ± 0.01 | 8.07 ± 0.37 | 21.31 ± 0.98 | 26.66 ± 1.06 | 23.04 ± 0.23 | 11.46 ± 0.07 |

| Control d | 2.97 ± 0.01 | 11.96 ± 0.01 | 22.22 ± 0.02 | 29.67 ± 0.23 | 27.35 ± 0.17 | 11.78 ± 0.11 |

2.2.2. Inhibition of Mitochondrial Reductases

2.2.3. Inhibition of Membrane Sterol Biosynthesis

3. Experimental Section

3.1. In Vitro Anti-trypomastigotes Assay

3.2. In Vivo Studies

3.2.1. Mice and Parasites

3.2.2. Treatment

3.2.3. Treatment Outcome

3.3. 1H-NMR Study of the Excreted Metabolites

3.4. Reductases Mitochondrial Inhibition Assay

3.5. Inhibition of Membrane Sterols Biosynthesis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maya, J.D.; Orellana, M.; Ferreira, J.; Kemmerling, U.; López-Muñoz, R.; Morello, A. Chagas disease: Present status of pathogenic mechanisms and chemotherapy. Biol. Res. 2010, 43, 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- WHO; GHO. World Health Organization: Global Health Observatory Data Repository; WHO, GHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Volume 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, M.P.; Croft, S.L. Management of trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis. Br. Med. Bull. 2012, 104, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekiel, V.; Alba-Soto, C.D.; González Cappa, S.M.; Postan, M.; Sánchez, D.O. Identification of vaccines candidates against Trypanosoma cruzi by immunization with sequential fractions of an epimastigote-subtracted trypomastigote cDNA expression library. Vaccine 2009, 27, 1323–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerecetto, H.; González, M. Synthetic medicinal chemistry in chagas’ disease: Compounds at the final stage of “hit-to-lead” phase. Pharmaceuticals 2010, 3, 810–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.M.; Robinson, H. Studies in the Eupatorieae (Asteraceae), CXXXIX. A new genus, Aristeguietia. Phytologia 1975, 30, 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, J.A.; Bogenschutz-Godwin, M.J.; Ottesen, A.R. Duke’s Handbook of Medicinal Plants of Latin America; Taylor Francis Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 310–311. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, O.P.; Dawra, R.K.; Kurada, N.P.; Sharma, P.D. A review of the toxicosis and biological properties of the genus Eupatorium. Nat. Toxins 1998, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woerdenbag, H.J. Eupatorium cannabinum L. A review emphasizing the sesquiterpene lactones and their biological activity. Pharm. Weekbl. Sci. Ed. 1986, 8, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Solis, M. Vademecum de Plantas Medicinales del Ecuador; Abya-Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, R.; Pitman, N.; León-Yánez, S.; Jorgensen, P.M. Libro Rojo de Las Plantas Endémicas del Ecuador; Publicaciones del Herbario QCA de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- El-Seedi, H.R.; Ohara, T.; Sata, N.; Nishiyama, S. Antimicrobial diterpenoids from Eupatorium glutinosum (Asteraceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 81, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Seedi, H.R.; Sata, N.; Torssell, K.B.G.; Nishiyama, S. New labdene diterpenes from Eupatorium glutinosum. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 728–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, M.J.; Bermejo, P.; Sanchez Palomino, S.; Chiriboga, X.; Carrasco, L. Antiviral activity of some South American medicinal plants. Phytother. Res. 1999, 13, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriboga, X.; Miño, P. Antimicrobial activity of Aristeguietia glutinosa. Escuela de Bioquímica y Farmacia, Facultad de Ciencias Químicas, Universidad Central de Ecuador, Ecuador; Unpublished work. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, J.; Lavaggi, M.L.; Cabrera, M.; Rodríguez, A.; Miño, P.; Chiriboga, X.; Cerecetto, H.; González, M. Bioactive-guided identification of labdane diterpenoids from aerial parts of Aristeguietia glutinosa Lam. as anti-Trypanosoma cruzi agents. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 1139–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Benitez, D.; Cabrera, M.; Hernández, P.; Boiani, L.; Lavaggi, M.L.; di Maio, R.; Yaluff, G.; Serna, E.; Torres, S.; Ferreira, M.E.; et al. 3-Trifluoromethylquinoxaline N,N'-dioxides as anti-trypanosomatid agents. Identification of optimal anti-T. cruzi agents and mechanism of action studies. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 3624–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moreno, M.; Fernandez-Becerra, M.C.; Castilla-Calvente, J.J.; Osuna, A. Metabolic studies by 1H NMR of different forms of Trypanosoma cruzi as obtained by “in vitro” culture. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1995, 133, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Valle, C.M.; Castilla-Calvente, J.; Sánchez-Moreno, M.; Moraleda-Lindez, V.; Barbe, J.; Osuna, A. Activity and mode of action of acridine compounds against Leishmania donovani. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 1996, 40, 684–690. [Google Scholar]

- Boiani, L.; Aguirre, G.; González, M.; Cerecetto, H.; Chidichimo, A.; Cazzulo, J.J.; Bertinaria, M.; Guglielmo, S. Furoxan-, alkylnitrate-derivatives and related compounds as anti-trypanosomatid agents: Mechanism of action studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 7900–7907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiani, M.; Boiani, L.; Merlino, A.; Hernández, P.; Chidichimo, A.; Cazzulo, J.J.; Cerecetto, H.; González, M. Second generation of 2H-benzimidazole 1,3-dioxide derivatives as anti-trypanosomatid agents: Synthesis, biological evaluation, and mode of action studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 4426–4433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringaud, F.; Riviere, L.; Coustou, V. Energy metabolism of trypanosomatids: Adaptation toavailable carbon sources. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2006, 149, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moreno, M.; Gómez-Contreras, F.; Navarro, P.; Marín, C.; Ramírez-Macías, I.; Olmo, F.; Sanz, A.M.; Campayo, L.; Cano, C.; Yunta, M.J. In vitro leishmanicidal activity of imidazole- or pyrazole-based benzo[g]phthalazine derivatives against Leishmania infantum and Leishmania braziliensis species. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.; Varela, J.; Correia, I.; Birriel, E.; Castiglioni, J.; Moreno, V.; Costa Pessoa, J.; Cerecetto, H.; González, M.; Gambino, D. A new series of heteroleptic oxidovanadium (IV) compounds with phenanthroline-derived co-ligands: Selective Trypanosoma cruzi growth inhibitors. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 11900–11911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, D.; Casanova, G.; Cabrera, G.; Galanti, N.; Cerecetto, H.; González, M. Initial studies on mechanism of action and cell death of active N-oxide-containing heterocycles in Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes in vitro. Parasitology 2014, 141, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.W.; McLeod, R.; Rice, D.W.; Ginger, M.; Chance, M.L. Fatty acid and sterol metabolism: Potential antimicrobial targets in apicomplexan and trypanosomatid parasitic protozoa. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2003, 126, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina, J.A.; Vivas, J.; Visbal, G.; Contreras, L.M. Modification of the sterol composition of Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi epimastigotes by delta 24(25)-sterol methyl transferase inhibitors and their combinations with ketoconazole. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1995, 73, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liendo, A.; Visbal, G.; Piras, M.M.; Piras, R.; Urbina, J.A. Sterol composition and biosynthesis in Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1999, 104, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, W.; Rodrigues, J.C. Sterol biosynthesis pathway as target for antitrypanosomatid drugs. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2009, 642502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina, J.A. Ergosterol biosynthesis and drug development for Chagas disease. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.L.; Soares, M.J.; Probst, C.M.; Krieger, M.A. Trypanosoma cruzi Response to Sterol Biosynthesis Inhibitors: Morphophysiological Alterations Leading to Cell Death. PLoS One 2013, 8, e55497. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, M.E.; Figueroa, L.I.; Fariña, J.I. Synergistic antifungal activity of statin-azole associations as witnessed by Saccharomyces cerevisiae- and Candida utilis-bioassays and ergosterol quantification. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2013, 30, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, M.I.; Gruber, A.; Vazquez, A.M.; Cortés, A.; Levin, M.J.; González, A.; Degrave, W.; Rondinelli, E.; Zingales, B.; Ramirez, J.L.; et al. Molecular karyotype of clone CL Brener chosen for the Trypanosoma cruzi genome project. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1995, 71, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.E.; Cebrián-Torrejón, G.; Segovia Corrales, A.; Vera de Bilbao, N.; Rolón, M.; Vega Gomez, C.; Leblanc, K.; Yaluff, G.; Schinini, A.; Torres, S.; et al. Zanthozylum chiloperone leaves extract: First sustainable Chagas disease treatment. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestrelab Research. Available online: http://mestrelab.com (accessed on 15 October 2013).

- Gerpe, A.; Alvarez, G.; Benítez, D.; Boiani, L.; Quiroga, M.; Hernández, P.; Sortino, M.; Zacchino, S.; González, M.; Cerecetto, H. 5-Nitrofuranes and 5-nitrothiophenes with anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity and ability to accumulate squalene. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 7500–7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds (1) and (2) are available from the authors.

© 2014 by the authors. licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Varela, J.; Serna, E.; Torres, S.; Yaluff, G.; De Bilbao, N.I.V.; Miño, P.; Chiriboga, X.; Cerecetto, H.; González, M. In Vivo Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi Activity of Hydro-Ethanolic Extract and Isolated Active Principles from Aristeguietia glutinosa and Mechanism of Action Studies. Molecules 2014, 19, 8488-8502. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19068488

Varela J, Serna E, Torres S, Yaluff G, De Bilbao NIV, Miño P, Chiriboga X, Cerecetto H, González M. In Vivo Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi Activity of Hydro-Ethanolic Extract and Isolated Active Principles from Aristeguietia glutinosa and Mechanism of Action Studies. Molecules. 2014; 19(6):8488-8502. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19068488

Chicago/Turabian StyleVarela, Javier, Elva Serna, Susana Torres, Gloria Yaluff, Ninfa I. Vera De Bilbao, Patricio Miño, Ximena Chiriboga, Hugo Cerecetto, and Mercedes González. 2014. "In Vivo Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi Activity of Hydro-Ethanolic Extract and Isolated Active Principles from Aristeguietia glutinosa and Mechanism of Action Studies" Molecules 19, no. 6: 8488-8502. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19068488

APA StyleVarela, J., Serna, E., Torres, S., Yaluff, G., De Bilbao, N. I. V., Miño, P., Chiriboga, X., Cerecetto, H., & González, M. (2014). In Vivo Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi Activity of Hydro-Ethanolic Extract and Isolated Active Principles from Aristeguietia glutinosa and Mechanism of Action Studies. Molecules, 19(6), 8488-8502. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19068488