Polymer-Supported Raney Nickel Catalysts for Sustainable Reduction Reactions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Preparation

3. Application of Polymer-Supported Raney Catalysts in Clean Preparation of n-Butanol

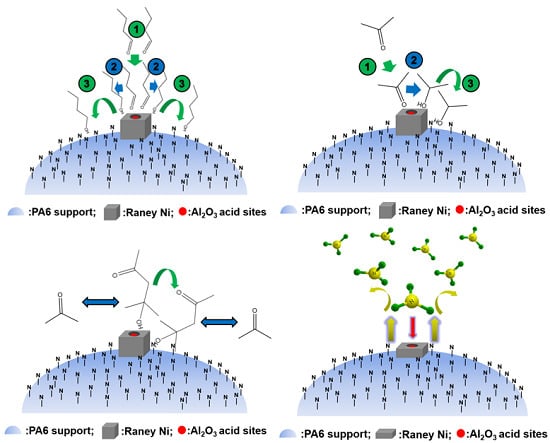

4. Application of Polymer-Supported Raney Catalysts in the Hydrogenation of Acetone to Isopropanol

5. Application of Polymer-Supported Raney Catalysts in Hydroamination of Acetone to Isopropylamine

6. Application of Polymer-Supported Raney Catalysts in Other Chemical Reactions

7. Outlook

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, W.C.; Czarnecki, L.J.; Pereira, C.J. Preparation, characterization, and performance of a novel fixed-bed raney catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1989, 28, 1764–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouilloux, P. The nature of raney nickel, its adsorbed hydrogen and its catalytic activity for hydrogenation reactions (review). Appl. Catal. 1983, 8, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, M.B.; Wang, S.-C.P.; Montgomery, S.R. Synthesis of Aliphatic Polyamines. U.S. Patent 4,721,811, 26 January 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Shimazu, K.; Tateno, Y.; Magara, M.; Okamoto, N.; Ohshima, T.; Nagasawa, M. Raney Catalyst, Process for Producing It and Process for Producing a Sugar-Alcohol Using the Same. U.S. Patent 6,414,201, 2 July 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Breitscheidel, B.; Walter, M.; Kratz, D.; Schulz, G.; Sauerwald, M. Method for the Hydrogenation of Carbonyl Compounds. U.S. Patent 6,207,865, 27 March 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, J.R.; Coville, N.J.; Sofianos, A.C.; Copperthwaite, R.G. Raney copper catalysts for the water-gas shift reaction: I. Preparation, activity and stability. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 1997, 164, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, P.; Burmeister, R.; Despeyroux, B.; Moesinger, H.; Krause, H.; Deller, K. Catalyst Precursor for an Activated Raney Metal Fixed-Bed Catalyst, an Activated Raney Metal Fixed-Bed Catalyst and a Process for Its Preparation and Use, and a Method of Hydrogenating Organic Compounds Using Said Catalyst. U.S. Patent 5,536,694, 16 July 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, T.; Burmeister, R.; Arntz, D.; Weber, K.-L.; Berweiler, M. Process for the Production of 3-Aminoethyl-3,5,5-Trimethylcyclohexyl Amine. U.S. Patent 5,679,860, 12 October 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ostgard, D.; Moebus, K.; Berweiler, M.; Bender, B.; Stein, G. Fixed Bed Catalysts. U.S. Patent 6,489,521, 3 December 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Degelmann, H.; Kowalczyk, J.; Kunz, M.; Schuettenhelm, M. Process for the Hydrogenation of Sugars Using a Shell Catalys. U.S. Patent 5,936,081, 10 August 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Haake, M.; Doersam, G.; Boos, H. Thin Layer Catalysts Based on Raney Alloys, and Method for the Production Thereof. U.S. Patent 6,998,366, 14 February 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W.C.; Lundsager, C.B.; Spotnitz, R.M. Shaped Catalyst and Process for Making It. U.S. Patent 4,826,799, 2 May 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W.C.; Lundsager, C.B.; Spotnitz, R.M. Shaped Catalysts and Processes. U.S. Patent 4,895,994, 23 January 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Vicari, M.; Flick, K.; Melder, J.-P.; Schnurr, W.; Wulff-Doering, J. Process for the Production of a Hydrogenation Catalyst. U.S. Patent 5,733,838, 31 March 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Breitscheidel, B.; Diehlmann, U.; Ruehl, T.; Weiguny, S. Fixed-Bed Raney Metal Catalyst, Its Preparation and the Hydrogenation of Polymers Using This Catalyst. U.S. Patent 6,121,188, 19 September 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, A.; Berweiler, M.; Bender, B.; Kempf, B. Shaped, Activated Metal, Fixed-Bed Catalyst. U.S. Patent 6,262,307, 17 July 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, S.D.; Anderson, R.B. The structure of raney nickel: IV. X-ray diffraction studies. J. Catal. 1971, 23, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; Tian, B.; Peng, H.; Dai, W.; Qiao, J. Effect of polyamide on selectivity of its supported raney ni catalyst. Sci. China Chem. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; Peng, H.; Dai, W.; Qiao, J. Polymer-supported catalysts for clean preparation of n-butanol. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 2499–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, H.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, X.; Peng, H.; Qiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S.; Dai, W. Method for Catalytic Distillation of c4Hydrocarbons. Patent CN104513119A, 15 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Jiang, H.; Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Qiao, J.; Peng, H. Supported Catalyst and Active Form Thereof, and Preparation Method and Use Thereof. Patent WO2014023220, 13 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Jiang, H.; Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Qiao, J.; Peng, H. Supported Catalyst and Preparation Method Thereof. Patent CN103566976A, 12 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, H.; Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; Dai, W.; Qiao, J.; Peng, H.; Yue, Y.; Wang, Y. Supported Catalyst for Selective Hydrogenation of Catalytic Distillation and Its Preparetion Method and Use Thereof. Patent CN104511312A, 15 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Dai, W.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Lu, S.; Qiao, J. Selective Hydrogenation Method of Pyrolysis Gasoline. Patent CN104513671A, 15 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Jiang, H.; Yin, M.; Zhang, X.; Peng, H.; Wang, H.; Dai, W.; Qiao, J. Catalyst for Low-Temperature Methanation and Its Preparetion Method Thereof. Patent CN104511314A, 15 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Jiang, H.; Peng, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Dai, W.; Qiao, J. Method for Liquid-Phase Hydrogenation of Decene Aldehyde to Decanol. Patent CN104513135A, 15 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Jiang, H.; Peng, H.; Zhang, X.; Dai, W.; Qiao, J. Method of Hydrogenation of Benzene toCyclohexane. Patent CN104513121A, 15 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Jiang, H.; Dai, W.; Zhang, X.; Peng, H.; Wang, H.; Qiao, J. Method for Liquid-Phase Hydrogenation of Decene Aldehyde to Decanol. Patent CN104513131A, 15 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Jiang, H.; Dai, W.; Zhang, X.; Peng, H.; Wang, H.; Qiao, J. Method for Selective Hydrogenation of Aldehydes to Alcohols. Patent CN104513130A, 15 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Jiang, H.; Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Peng, H.; Lu, S.; Wang, H.; Qiao, J. N-Butanol Composition from Hydrogenation of n-Butylaldehyde. Patent CN104513134A, 15 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Jiang, H.; Peng, H.; Zhang, X.; Lu, S.; Qiao, J. Method for Hydrogenation of Alcohols to Remove Trace of Aldehydes. Patent CN104513132A, 15 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Jiang, H.; Yi, S.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, J.; Peng, H.; Lu, S. Method for Selective Hydrogenation of Pyrolysis Gasoline. Patent CN104419454A, 18 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, S.; Jiang, H.; Yin, M.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, J.; Peng, H.; Lu, S.; Dai, W. Method for Catalytic Hydrogenation. Patent CN104415715A, 18 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, S.; Jiang, H.; Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, J.; Peng, H.; Dai, W. Method for Hydrogenation of Unsaturated Hydrocarbons. Patent CN104419453A, 18 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.K.; Choi, J.H.; Song, J.H.; Yi, J.; Song, I.K. Etherification of n-butanol to di-n-butyl ether over HnXW12O40 (X= CO2+, B3+, Si4+, and P5+) keggin heteropolyacid catalysts. Catal. Commun. 2012, 27, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Kim, J.K.; Park, D.R.; Park, S.; Yi, J.; Song, I.K. Etherification of n-butanol to di-n-butyl ether over H3PMo12−xWxO40 (X = 0, 3, 6, 9, 12) keggin and H6P2Mo18−xWxO62 (X = 0, 3, 9, 15, 18) wells-dawson heteropolyacid catalysts. Catal. Commun. 2011, 14, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, M.; Salagre, P.; Cesteros, Y.; Medina, F.; Sueiras, J.E. Evolution of several Ni and Ni-MgO catalysts during the hydrogenation reaction of adiponitrile. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2004, 272, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Xue, M.; Chen, H.; Shen, J. The effect of surface acidic and basic properties on the hydrogenation of aromatic rings over the supported nickel catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 162, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, M.A.; Kozhevnikova, E.F.; Kozhevnikov, I.V. Hydrogenation of methyl isobutyl ketone over bifunctional Pt-zeolite catalyst. J. Catal. 2012, 293, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Unnikrishnan, R. Selective hydrogenation of acetone to methyl isobutyl ketone (MIBK) over co-precipitated Ni/Al2O3 catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 1996, 145, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Xu, M.; Huai, X. High temperature catalytic hydrogenation of acetone over raney Ni for chemical heat pump. J. Therm. Sci. 2014, 23, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | T (°C) | Conversion (%) | n-Butyl Ether (wt %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raney Ni/PP | 100 | 99.99 | 0.013 |

| 110 | 100 | 0.053 | |

| 120 | 100 | 0.095 | |

| 140 | 100 | 0.499 | |

| Raney Ni/MAHPP | 100 | 99.99 | 0.300 |

| 110 | 100 | 0.632 | |

| 120 | 100 | 1.049 | |

| 140 | 100 | 1.843 | |

| Ni/Al2O3 | 100 | 100 | 0.159 |

| 110 | 100 | 0.292 | |

| 120 | 100 | 0.677 | |

| 140 | 100 | 1.706 | |

| Raney Ni/PA | 100 | 99.99 | undetected |

| 110 | 100 | undetected | |

| 120 | 100 | 0.015 | |

| 140 | 100 | 0.016 |

| Inorganic Support | Organic Support | Organic Support with Acid or Alkaline Group Which Can Adsorb n-Butanol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support with alkalinity or acidity | Al2O3 (acidity) | PP (neutral) | PP-g-MAH (acidity) | PA6 (alkalinity) |

| n-Butyl ether content | High | Low | Very high | Very low to undetectable |

| Catalyst | Conversion (%) | Selectivity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isopropanol | Isopropyl Ether | MIBC | ||

| Ni/Al2O3 | 98.97 | 99.87 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Raney Ni/Al2O3 | 99.71 | 99.91 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Granular Raney Ni | 99.76 | 99.94 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Raney Ni/PA | 99.75 | 100.00 | undetectable | undetectable |

| Catalyst | Conversion (%) | Selectivity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isopropylamine | DIPA | Isopropanol | ||

| Ni/Al2O3 | 99.38 | 79.06 | 7.00 | 13.94 |

| Raney Ni/Al2O3 | 98.18 | 71.63 | 3.83 | 24.54 |

| Granular Raney Ni | 96.49 | 56.83 | 3.52 | 39.65 |

| Raney Ni/PA | 90.69 | 37.95 | undetectable | 62.05 |

© 2016 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, H.; Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; Dai, W.; Qiao, J. Polymer-Supported Raney Nickel Catalysts for Sustainable Reduction Reactions. Molecules 2016, 21, 833. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21070833

Jiang H, Lu S, Zhang X, Dai W, Qiao J. Polymer-Supported Raney Nickel Catalysts for Sustainable Reduction Reactions. Molecules. 2016; 21(7):833. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21070833

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Haibin, Shuliang Lu, Xiaohong Zhang, Wei Dai, and Jinliang Qiao. 2016. "Polymer-Supported Raney Nickel Catalysts for Sustainable Reduction Reactions" Molecules 21, no. 7: 833. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21070833

APA StyleJiang, H., Lu, S., Zhang, X., Dai, W., & Qiao, J. (2016). Polymer-Supported Raney Nickel Catalysts for Sustainable Reduction Reactions. Molecules, 21(7), 833. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21070833