DNA Three Way Junction Core Decorated with Amino Acids-Like Residues-Synthesis and Characterization †

Abstract

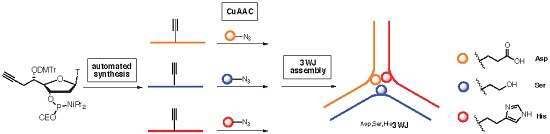

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of Convertible Nucleotide

2.2. Synthesis of Functionalized ODNs

2.3. Three Way Junctions Assemblies and Thermal Denaturation Studies

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General and Nucleosides Synthesis

3.2. General ODN Synthesis and UV Thermal Denaturation Study

3.2.1. Automated Synthesis

3.2.2. CuACC Protocol and Deprotection of 5′-C-Functionalized ODNs

3.2.3. PAGE Protocol

3.2.4. UV Thermal Denaturation Study

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nissen, P.; Hansen, J.; Ban, N.; Moore, P.B.; Steitz, T.A. The Structural Basis of Ribosome Activity in Peptide Bond Synthesis. Science 2000, 289, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiller, D.A.; Singh, V.; Zhong, M.; Strobel, S.A. A two-step chemical mechanism for ribosome-catalysed peptide bond formation. Nature 2011, 476, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandsen, B.M.; Hesser, A.R.; Castner, M.A.; Chandra, M.; Silverman, S.K. DNA-Catalyzed Hydrolysis of Esters and Aromatic Amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16014–16017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Avins, J.L.; Klauser, P.C.; Brandsen, B.M.; Lee, Y.; Silverman, S.K. DNA-Catalyzed Amide Hydrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2106–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedstrom, L. Serine Protease Mechanism and Specificity. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 4501–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollenstein, M. Nucleoside Triphosphates-Building Blocks for the Modification of Nucleic Acids. Molecules 2012, 17, 13569–13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollenstein, M. Deoxynucleoside triphosphates bearing histamine, carboxylic acid, and hydroxyl residues-synthesis and biochemical characterization. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 5162–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catry, M.; Madder, A. Synthesis of Functionalised Nucleosides for Incorporation into Nucleic Acid-Based Serine Protease Mimics. Molecules 2007, 12, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catry, M.A.; Gheerardijn, V.; Madder, A. Surprising duplex stabilisation upon mismatch introduction within triply modified duplexes. Bioorg. Chem. 2010, 38, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kel’in, A.V.; Zlatev, I.; Harp, J.; Jayaraman, M.; Bisbe, A.; O′Shea, J.; Taneja, N.; Manoharan, R.M.; Khan, S.; Charisse, K.; et al. Structural Basis of Duplex Thermodynamic Stability and Enhanced Nuclease Resistance of 5′-C-Methyl Pyrimidine-Modified Oligonucleotides. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 2261–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banuls, V.; Escudier, J.-M.; Zedde, C.; Claparols, C.; Donnadieu, B.; Plaisancié, H. Stereoselective Synthesis of (5′S)-5′-C-(5-Bromo-2-penten-1-yl)-2′-deoxyribofuranosyl Thymine, a New Convertible Nucleoside. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 4693–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlyakhtenko, L.S.; Potaman, V.N.; Sinden, R.R.; Gall, A.A.; Lyubchenko, Y.L. Structure and dynamics of three-way DNA junctions: atomic force microscopy studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 3472–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabir, T.; Toulmin, A.; Ma, L.; Jones, A.C.; McGlynn, P.; Schröder, G.F.; Magennis, S.W. Branchpoint Expansion in a Fully Complementary Three-Way DNA Junction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6280–6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, M.H.; Blakskjær, P.; Petersen, L.K.; Hansen, T.H.; Højfeldt, J.W.; Gothelf, K.V.; Hansen, N.J.V. A Yoctoliter-Scale DNA Reactor for Small-Molecule Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duprey, J.-L.H.A.; Takezawa, Y.; Shionoya, M. Metal-Locked DNA Three-Way Junction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 52, 1212–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R.P.; Berry, R.M.; Turberfield, A.J. The single-step synthesis of a DNA tetrahedron. Chem. Commun. 2004, 1372–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, A.; Kobbe, D.; Focke, M. DNA–DNA kissing complexes as a new tool for the assembly of DNA nanostructures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 1502–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, H.C.; Finn, M.G.; Sharpless, K.B. Click Chemistry: Diverse Chemical Function from a Few Good Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramlich, P.M.E.; Wirges, C.T.; Manetto, A.; Carell, T. Postsynthetic DNA Modification through the Copper-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8350–8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugan, R.N.; Park, J.-E.; Lim, D.; Ahn, M.; Cheong, C.; Kwon, T.; Nam, K.-Y.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, B.Y.; Yoon, D.-Y.; et al. Development of cyclic peptomer inhibitors targeting the polo-box domain of polo-like kinase 1. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 2623–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijtmans, M.; de Graaf, C.; de Kloe, G.; Istyastono, E.P.; Smit, J.; Lim, H.; Boonnak, R.; Nijmeijer, S.; Smits, R.A.; Jongejan, A.; et al. Triazole Ligands Reveal Distinct Molecular Features That Induce Histamine H4 Receptor Affinity and Subtly Govern H4/H3 Subtype Selectivity. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 1693–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.H.; Taniguchi, M.; Tegg, D.; Moffatt, J.G. 4′-Substituted nucleosides. 5. Hydroxymethylation of nucleoside 5′-aldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudier, J.-M.; Tworkowski, I.; Bouziani, L.; Gorrichon, L. Synthèse stéréosélective de thymidine substituée en C-5′. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 4689–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolk, L.; Pøhlsgaard, J.; Jepsen, A.S.; Hansen, L.H.; Nielsen, H.; Steffansen, S.I.; Sparving, L.; Nielsen, A.B.; Vester, B.; Nielsen, P. A Click Chemistry Approach to Pleuromutilin Conjugates with Nucleosides or Acyclic Nucleoside Derivatives and Their Binding to the Bacterial Ribosome. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 4957–4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, D.; Escudier, J.-M.; Amigues, E.; Schulz, J.; Vitry, C.; Bordenave, T.; Szlosek-Pinaud, M.; Fouquet, E. A click chemistry approach to the efficient synthesis of modified nucleosides and oligonucleotides for PET imaging. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 1230–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banuls, V.; Escudier, J.-M. Allylsilanes in the preparation of 5′-C-hydroxy or bromo alkylthymidines. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 5831–5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Pitsch, S. Synthesis and pairing properties of oligoribonucleotide analogues containing a metal-binding site attached to β-d-allofuranosyl cytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 4315–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruthers, M.H. Chemical synthesis of DNA and DNA analogs. Acc. Chem. Res. 1991, 24, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourceau, G.; Meyer, A.; Vasseur, J.-J.; Morvan, F. Synthesis of Mannose and Galactose Oligonucleotide Conjugates by Bi-click chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 1218–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourceau, G.; Meyer, A.; Chevolot, Y.; Souteyrand, E.; Vasseur, J.-J.; Morvan, F. Oligonucleotide Carbohydrate-Centered Galactosyl Cluster Conjugates Synthesized by Click and Phosphoramidite Chemistries. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 21, 1520–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trafelet, H.; Parel, S.P.; Leumann, C.J. Oligodeoxynucleotide Duplexes Containing (5′S)-5′-C-Alkyl-Modified 2′-Deoxynucleosides: Can an Alkyl Zipper across the DNA Minor-Groove Enhance Duplex Stability? Helv. Chim. Acta 2003, 86, 3671–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Middleton, P.J.; Lin, C.; Pietrzkowski, Z. Biophysical and biochemical properties of oligodeoxynucleotides containing 4′-C- and 5′-C-substituted thymidines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyst, D.; Gheerardijn, V.; Fehér, K.; Van Gasse, B.; Van Den Begin, J.; Martins, J.C.; Madder, A. Identification of a pKa-regulating motif stabilizing imid azole-modified double-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sample Availability: Not available.

| Sequences | Tm °C | Tm °C (ΔTm °C) 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ΔTm °C) 1 Duplex | 3WJ | ||||

| wtS1/wtS′1 5′GCGACCTATTGCAAGTGG 3′CGCTGGATAACGTTCACC | 66 (Tm1) |  | wtS1, wtS2, wtS3 (wt3WJ) 43 (Tm4) | ||

| wtS2/wtS′2 5′CCACTTGCATGTGTGTGCC 3′GGTGAACGTACACACACGG | 69 (Tm2) | ||||

| wtS3/wtS′3 5′GGCACACACTTAGGTCGC 3′CCGTGTGTGAATCCAGCG | 68 (Tm3) | ||||

| alkS1/wtS′1 5′GCGACCTATTGCAAGTGG 3′CGCTGGATAACGTTCACC | 65 (−1) | alkS1, wtS2, wtS3 43 (0) wtS1, alkS2, alkS3 43 (0) | wtS1, alkS2, wtS3 43 (0) alkS1, wtS2, alkS3 42 (−1) | wtS1, wtS2, alkS3 43 (0) alkS1, alkS2 wtS3 43 (0) | alkS1, alkS2, alkS3 (alk3WJ) 43 (0) |

| alkS2/wtS′2 5′CCACTTGCATGTGTGTGCC 3′GGTGAACGTACACACACGG | 68 (−1) | ||||

| alkS3/wtS′3 5′GGCACACACTTAGGTCGC 3′CCGTGTGTGAATCCAGCG | 66 (−2) | ||||

| AspS1/wtS′1 5′GCGACCTATAspTGCAAGTGG 3′CGCTGGATA ACGTTCACC | 64 (−2) | AspS1, wtS2, wtS3 42 (−1) AspS1, SerS2, wtS3 43 (0) | wtS1, SerS2, wtS3 44 (+1) AspS1, wtS2, HisS3 43 (0) | wtS1, wtS2, HisS3 44 (+1) wtS1, SerS2, HisS3 44 (+1) | AspS1, SerS2, HisS3 43 (0) |

| SerS2/wtS′2 5′CCGCTTGCATSerGTGTGTGCC 3′GGCGAACGTACACACACGG | 68 (−1) | ||||

| HisS3/wtS′3 5′GGCACACACTHisTAGGTCGC 3′CCGTGTGTGAATCCAGCG | 68 (0) | ||||

| Sequence | CuAAC Conditions | tr (min) | [M − H]− Calcd. | [M − H]− Found | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wtS1 | 5′GCGACCTATTGCAAGTGG | - | 6.35 1 | 5538.6 | 5539.9 |

| wtS2 | 5′CCACTTGCATGTGTGTGCC | - | 6.40 1 | 5769.7 | 5771.0 |

| wtS3 | 5′GGCACACACTTAGGTCGC | - | 6.27 1 | 5483.6 | 5484.3 |

| alkS1 | 5′GCGACCTATTGCAAGTGG | - | 6.52 2 | 5576.6 | 5577.0 |

| alkS2 | 5′CCACTTGCATGTGTGTGCC | - | 6.57 2 | 5807.8 | 5806.7 |

| alkS3 | 5′GGCACACACTTAGGTCGC | - | 6.49 2 | 5521.6 | 5520.8 |

| AspS1 | 5′GCGACCTATAspTGC AAGTGG | 1, TBTA, 1 h | 5.04 2 | 5691.7 | 5692.3 |

| AspS2 | 5′CCACTTGCATGTAspGTGTGCC | 1, 3 h | 5.18 2 | 5922.9 | 5923.1 |

| AspS3 | 5′GGCACACACTAspTAGGTCGC | 1, 3 h | 4.75 2 | 5636.7 | 5636.8 |

| SerS2 | 5′CCACTTGCATGTSerGTGTGCC | 3, 1.5 h | 5.74 2 | 5894.9 | 5893.7 |

| HisS3 | 5′GGCACACACTHisTAGGTCGC | 2, 0.5 h | 6.02 2 | 5658.7 | 5660.4 |

© 2016 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Addamiano, C.; Gerland, B.; Payrastre, C.; Escudier, J.-M. DNA Three Way Junction Core Decorated with Amino Acids-Like Residues-Synthesis and Characterization. Molecules 2016, 21, 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21091082

Addamiano C, Gerland B, Payrastre C, Escudier J-M. DNA Three Way Junction Core Decorated with Amino Acids-Like Residues-Synthesis and Characterization. Molecules. 2016; 21(9):1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21091082

Chicago/Turabian StyleAddamiano, Claudia, Béatrice Gerland, Corinne Payrastre, and Jean-Marc Escudier. 2016. "DNA Three Way Junction Core Decorated with Amino Acids-Like Residues-Synthesis and Characterization" Molecules 21, no. 9: 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21091082

APA StyleAddamiano, C., Gerland, B., Payrastre, C., & Escudier, J. -M. (2016). DNA Three Way Junction Core Decorated with Amino Acids-Like Residues-Synthesis and Characterization. Molecules, 21(9), 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21091082