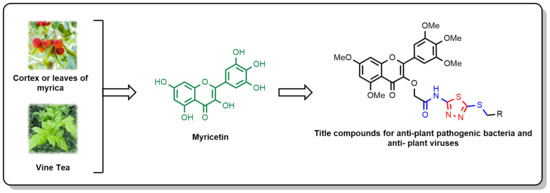

Design, Synthesis, and Biological Activity of Novel Myricetin Derivatives Containing Amide, Thioether, and 1,3,4-Thiadiazole Moieties

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. Antiviral Activities of the Title Compounds against Plant Pathogens In Vivo

2.3. Antiviral Activities of the Title Compounds against TMV In Vivo

3. Experimental

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. Synthesis Procedure for Intermediate 1

3.1.2. General Procedure for Preparation of Intermediates 2a–6p

3.1.3. General Procedure for Preparation of Intermediates 3a−3p

3.1.4. General Procedure for Preparation of Intermediate 4

3.1.5. General Procedure for Preparation of Title Compounds 5a−5p

3.2. Biological Assays

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, B.A.; Jin, L.H.; Yang, S.; Bhadury, P.S. Environment-friendly antiviral agents for plants; Springer Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- David, B.; Wolfender, J.L.; Dias, D.A. The pharmaceutical industry and natural products: Historical status and new trends. Phytochem. Rev. 2014, 14, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, S.O.; Dayan, F.E.; Romagni, J.G.; Rimando, A.M. Natural products as sources of herbicides: Current status and future trends. Weed Res. 2000, 40, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, F.E.; Cantrell, C.L.; Duke, S.O. Natural products in crop protection. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 4022–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesar, F.C.S.; Neto, F.C.; Porto, G.S.; Campos, P.M. Patent analysis: A look at the innovative nature of plant-based cosmetics. Quim. Nova 2017, 40, 840–847. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, S.D.; Latif, Z.; Gray, A.I. Natural Products Isolation; Springer Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Gan, X.; Zhou, D.; He, F.; Zeng, S.; Hu, D. Synthesis and antiviral activity of novel 1,4-pentadien-3-one derivatives containing a 1,3,4-thiadiazole moiety. Molecules 2017, 22, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcelik, B.; Kartal, M.; Orhan, I. Cytotoxicity, antiviral and antimicrobial activities of alkaloids, flavonoids, and phenolic acids. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yao, Y.S.; Lin, G.B.; Xie, Y.; Ma, P.; Li, G.W.; Meng, Q.C.; Wu, T. Preformulation studies of myricetin: A natural antioxidant flavonoid. Die Pharmazie 2014, 69, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ong, K.C.; Khoo, H.E. Biological effects of myricetin. Gen. Pharmacol. 1997, 29, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Du, Y.J.; Song, H.C. α-glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory activities of guava leaves. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Gao, M.H.; Huang, W.H.; Li, M.M.; Li, H.; Li, Y.L.; Zhang, X.Q.; Ye, W.C. Flavonoids from the seeds of hovenia acerba and their in vitro antiviral activity. J. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 6, 401–409. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, G.; Liao, Y.; Gong, D. Myricetin inhibits the generation of superoxide anion by reduced form of xanthine oxidase. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1569–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.J.; Su, H.; Yan, J.Y.; Li, N.; Song, Z.Y.; Wang, H.J.; Huo, L.G.; Wang, F.; Ji, W.S.; Qu, X.J.; et al. Chemopreventive effect of myricetin, a natural occurring compound, on colonic chronic inflammation and inflammation-driven tumorigenesis in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 1131–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, T.K.; Jung, I.; Kim, M.E.; Bae, S.K.; Lee, J.S. Anti-cancer activity of myricetin against human papillary thyroid cancer cells involves mitochondrial dysfunction-mediated apoptosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Lim, W.; Bazer, F.W.; Song, G. Myricetin suppresses invasion and promotes cell death in human placental choriocarcinoma cells through induction of oxidative stress. Cancer Lett. 2017, 399, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, A.W.; Chen, Y.Q.; Zhao, L.Q.; Feng, J.G. Myricetin induces apoptosis and enhances chemosensitivity in ovarian cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 4974–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhong, X.M.; Wang, X.B.; Chen, L.J.; Ruan, X.H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.P.; Chen, Z.; Xue, W. Synthesis and biological activity of myricetin derivatives containing 1,3,4-thiadiazole scaffold. Chem. Cent. J. 2017, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, X.H.; Zhao, H.J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, L.J.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.H.; He, M.; Xue, W. Syntheses and Bioactivities of Myricetin Derivatives Containing Piperazine Acidamide Moiety. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 2018, 39, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, W.; Song, B.A.; Zhao, H.J.; Qi, X.B.; Huang, Y.J.; Liu, X.H. Novel myricetin derivatives: Design, synthesis and anticancer activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Ruan, X.H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.P.; Zhong, X.M.; Xie, Y.; Wang, X.B.; Huang, M.G.; Xue, W. Synthesis and antibacterial activities of myricetin derivatives containing acidamide moiety. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 2017, 38, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, G.M. A theoretical study on the aromaticity of thiadiazoles and related compounds. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 2001, 549, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Li, C.Y.; Wang, X.M.; Yang, Y.H.; Zhu, H.L. 1,3,4-thiadiazole: Synthesis, reactions, and applications in medicinal, agricultural, and materials chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5572–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vudhgiri, S.; Koude, D.; Veeragoni, D.K.; Misra, S.; Prasad, R.B.N.; Jala, R.C.R. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 5-fatty-acylamido-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2-thioglycosides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 3370–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.M.; Han, F.F.; He, M.; Hu, D.Y.; He, J.; Yang, S.; Song, B.A. Inhibition of tobacco bacterial wilt with sulfone derivatives containing an 1,3,4-oxadiazole moiety. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 1036–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, P.; Li, Z.N.; Yin, J.; He, M.; Xue, W.; Chen, Z.W.; Song, B.A. Synthesis and bioactivity evaluation of novel arylimines containing a 3-aminoethyl-2-((q-trifluoromethoxy) aniline)-4-(3H)-quinazolinone moiety. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 9575–9582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.G.; Ruan, X.H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.P.; Zhong, X.M.; Wang, X.B.; Xie, Y.; Xiao, W.; Xue, W. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of novel phosphorylated flavonoid derivatives. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2017, 192, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Bao, X.P. Synthesis of novel 1,2,4-triazole derivatives containing the quinazolinylpiperidinyl moiety and N-(substituted phenyl)acetamide group as efficient bactericides against the phytopathogenic bacterium xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 34005–34011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Zhao, Y.H.; Shan, W.L.; Hu, D.Y.; Chen, J.X.; Yang, S. Synthesis and antiviral activities of novel 1,4-pentadien-3-one derivatives bearing an emodin moiety. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2016, 27, 948–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, V.; Pathak, M.; Bhat, H.R.; Singh, U.P. Design, Facile Synthesis, and Antibacterial Activity of Hybrid 1,3,4-thiadiazole-1,3,5-triazine Derivatives Tethered via-S-Bridge. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2012, 80, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, B.Q.; Shi, Y.P.; Liu, Y.M.; Zhao, H.C.; Cheng, J. Synthesis and in vitro antitumor activity of 1,3,4-thiadiazole derivatives based on benzisoselenazolone. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2012, 23, 817–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y.; Li, X.W.; Zhi, S.; Wang, P.B.; Liu, D.K. Thiadiazole Derivatives. CN 102276625B, 17 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds 5a–5p are available from the authors. |

| Compd. | Inhibition Rate a/% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xac | Rs | Xoo | ||||

| 100 μg/mL | 50 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 50 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 50 μg/mL | |

| 5a | 75.7 ± 5.3 | 64.3 ± 3.1 | 70.4 ± 7.5 | 50.2 ± 6.5 | 59.1 ± 2.3 | 54.4 ± 2.9 |

| 5b | 54.7 ± 1.9 | 53.5 ± 1.1 | 41.5 ± 7.5 | 16.4 ± 0.9 | 51.7 ± 2.6 | 44.2 ± 3.4 |

| 5c | 51.3 ± 4.9 | 18.9 ± 2.6 | 68.7 ± 6.5 | 63.4 ± 4.6 | 62.7 ± 2.8 | 44.1 ± 6.7 |

| 5d | 39.3 ± 1.4 | 34.7 ± 1.7 | 35.3 ± 3.0 | 37.0 ± 2.0 | 59.1 ± 2.6 | 58.0 ± 1.7 |

| 5e | 44.4 ± 2.8 | 15.2 ± 5.3 | 78.0 ± 1.5 | 60.5 ± 3.1 | 69.8 ± 8.2 | 62.0 ± 3.0 |

| 5f | 75.0 ± 5.9 | 60.3 ± 3.6 | 33.5 ± 9.3 | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 68.4 ± 3.5 | 50.4 ± 2.5 |

| 5g | 89.2 ± 1.9 | 79.5 ± 1.6 | 29.7 ± 0.8 | 20.6 ± 0.7 | 65.6 ± 5.8 | 61.4 ± 1.5 |

| 5h | 74.3 ± 2.8 | 68.3 ± 5.6 | 41.5 ± 0.3 | 38.5 ± 2.0 | 69.5 ± 1.7 | 33.7 ± 2.8 |

| 5i | 89.5 ± 6.5 | 68.7 ± 2.7 | 85.6 ± 4.9 | 64.8 ± 1.7 | 78.3 ± 6.9 | 53.0 ± 1.8 |

| 5j | 41.5 ± 4.1 | 29.2 ± 3.0 | 66.3 ± 2.0 | 59.6 ± 4.9 | 44.4 ± 5.2 | 36.9 ± 3.9 |

| 5k | 73.5 ± 6.7 | 51.6 ± 2.7 | 28.9 ± 2.1 | 25.6 ± 1.1 | 48.3 ± 2.8 | 47.5 ± 2.5 |

| 5l | 75.3 ± 5.3 | 55.3 ± 4.1 | 34.9 ± 4.5 | 31.2 ± 4.9 | 54.1 ± 4.0 | 36.8 ± 1.7 |

| 5m | 72.6 ± 4.8 | 35.2 ± 1.7 | 41.4 ± 7.3 | 34.7 ± 5.8 | 55.3 ± 2.8 | 50.2 ± 1.0 |

| 5n | 55.3 ± 2.1 | 47.9 ± 1.4 | 52.5 ± 2.9 | 49.9 ± 4.2 | 44.8 ± 0.7 | 43.8 ± 3.4 |

| 5o | 55.6 ± 7.7 | 46.8 ± 7.0 | 33.2 ± 2.3 | 8.3 ± 0.8 | 77.6 ± 4.3 | 42.3 ± 1.6 |

| 5p | 67.4 ± 6.8 | 51.1 ± 7.0 | 36.7 ± 4.0 | 35.0 ± 1.3 | 47.8 ± 7.5 | 31.8 ± 2.6 |

| MYR b | 40.7 ± 4.8 | 31.1 ± 3.0 | 57.1 ± 7.5 | 44.2 ± 3.4 | 68.5 ± 8.0 | 53.2 ± 9.4 |

| BT c | 73.3 ± 8.2 | 55.0 ± 4.5 | 69.7 ± 1.9 | 57.6 ± 3.1 | 71.1 ± 3.8 | 36.5 ± 2.9 |

| TC c | 67.7 ± 3.7 | 44.3 ± 4.0 | 35.3 ± 3.8 | 18.9 ± 4.4 | 36.1 ± 1.3 | 35.8 ± 2.1 |

| Bacteria | Compd. | R | Toxic Regression Equation | r | EC50/(μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xac | 5a | CH3 | y = 1.2309x + 3.2852 | 0.9814 | 24.7 ± 2.7 |

| 5f | 2-F-Ph | y = 1.1496x+3.3598 | 0.9978 | 26.7 ± 1.3 | |

| 5g | 4-F-Ph | y = 1.3129x + 3.5997 | 0.9928 | 11.5 ± 1.8 | |

| 5h | 2-CH3-Ph | y = 1.3011x + 3.1703 | 0.9882 | 25.5 ± 3.2 | |

| 5i | 3-CH3-Ph | y = 1.5172x + 3.0628 | 0.9740 | 18.9 ± 2.6 | |

| 5l | 4-CF3-Ph | y = 1.0060x + 3.5803 | 0.9869 | 27.3 ± 2.9 | |

| BT a | - | y = 1.2497x + 3.0744 | 0.9755 | 34.7 ± 1.3 | |

| TC a | - | y = 1.1587x + 3.1306 | 0.9920 | 41.1 ± 3.7 | |

| Rs | 5a | CH3 | y = 1.0299x + 3.4622 | 0.9675 | 31.3 ± 2.5 |

| 5c | 2-Cl-Ph | y =0.7749x + 3.8771 | 0.9861 | 28.1 ± 4.2 | |

| 5e | 2,4-diCl-Ph | y = 1.7574x + 2.1963 | 0.9954 | 39.4 ± 3.4 | |

| 5i | 3-CH3-Ph | y = 2.0968x + 1.7437 | 0.9873 | 35.7 ± 1.6 | |

| BT a | - | y = 1.2725x + 2.6703 | 0.9839 | 67.2 ± 2.2 | |

| TC a | - | y = 1.2681x + 2.3203 | 0.9927 | 112.5 ± 4.7 | |

| Xoo | 5e | 2,4-diCl-Ph | y = 1.3410x + 2.9457 | 0.9951 | 34.0 ± 3.2 |

| 5f | 2-F-Ph | y = 1.3885x + 2.7900 | 0.9839 | 44.9 ± 3.5 | |

| 5h | 2-CH3-Ph | y = 2.0971x + 1.1978 | 0.9918 | 65.0 ± 2.1 | |

| 5i | 3-CH3-Ph | y = 1.3586x + 2.9710 | 0.9891 | 31.2 ± 2.4 | |

| 5o | 4-CF3-Ph | y = 1.8004x + 1.9332 | 0.9792 | 50.5 ± 5.7 | |

| BT a | - | y = 1.6145x + 1.7430 | 0.9887 | 45.3 ± 3.0 | |

| TC a | - | y = 1.8721x + 1.8993 | 0.9830 | 105.1 ± 4.6 |

| Compd. | R | Inhibition Rate a/% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curative | Protection | Inactivation | ||

| 5a | CH3 | 38.0 ± 6.3 | 40.0 ± 6.9 | 53.6 ± 5.4 |

| 5b | Ph | 26.0 ± 4.9 | 36.0 ± 6.0 | 71.5 ± 5.1 |

| 5c | 2-Cl-Ph | 27.1 ± 4.1 | 40.8 ± 7.1 | 72.9 ± 5.1 |

| 5d | 4-Cl-Ph | 35.6 ± 4.9 | 42.2 ± 7.3 | 62.0 ± 2.8 |

| 5e | 2,4-diCl-Ph | 22.3 ± 1.8 | 43.2 ± 4.6 | 76.7 ± 3.5 |

| 5f | 2-F-Ph | 42.2 ± 8.9 | 49.2 ± 8.4 | 61.2 ± 5.9 |

| 5g | 4-F-Ph | 49.9 ± 5.0 | 52.9 ± 5.2 | 73.3 ± 2.8 |

| 5h | 2-CH3-Ph | 31.0 ± 6.4 | 34.7 ± 5.7 | 58.1 ± 4.6 |

| 5i | 3-CH3-Ph | 44.2 ± 5.3 | 45.3 ± 7.2 | 57.0 ± 4.6 |

| 5j | 4-CH3O-Ph | 30.6 ± 1.0 | 54.5 ± 5.7 | 63.5 ± 4.9 |

| 5k | 3-CF3-Ph | 39.9 ± 4.2 | 46.4 ± 5.9 | 60.2 ± 3.9 |

| 5l | 4-CF3-Ph | 45.3 ± 4.1 | 49.9 ± 7.3 | 59.5 ± 6.2 |

| 5m | 3-pyridyl | 33.2 ± 4.8 | 32.2 ± 8.8 | 52.5 ± 5.5 |

| 5n | 4-pyridyl | 43.1 ± 3.3 | 36.1 ± 8.6 | 62.6 ± 3.3 |

| 5o | 2-Cl-5-thiazolyl | 33.8 ± 7.6 | 44.8 ± 5.9 | 65.3 ± 2.7 |

| 5p | 4-NO2-Ph | 35.9 ± 3.7 | 47.7 ± 2.4 | 64.6 ± 4.1 |

| MYR b | - | 36.7 ± 6.3 | 42.3 ± 6.5 | 51.5 ± 3.7 |

| RBV c | - | 40.6 ± 2.5 | 51.1 ±2.3 | 71.1 ± 4.2 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruan, X.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, S.; Guo, T.; Xia, R.; Chen, Y.; Tang, X.; Xue, W. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Activity of Novel Myricetin Derivatives Containing Amide, Thioether, and 1,3,4-Thiadiazole Moieties. Molecules 2018, 23, 3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23123132

Ruan X, Zhang C, Jiang S, Guo T, Xia R, Chen Y, Tang X, Xue W. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Activity of Novel Myricetin Derivatives Containing Amide, Thioether, and 1,3,4-Thiadiazole Moieties. Molecules. 2018; 23(12):3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23123132

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuan, Xianghui, Cheng Zhang, Shichun Jiang, Tao Guo, Rongjiao Xia, Ying Chen, Xu Tang, and Wei Xue. 2018. "Design, Synthesis, and Biological Activity of Novel Myricetin Derivatives Containing Amide, Thioether, and 1,3,4-Thiadiazole Moieties" Molecules 23, no. 12: 3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23123132

APA StyleRuan, X., Zhang, C., Jiang, S., Guo, T., Xia, R., Chen, Y., Tang, X., & Xue, W. (2018). Design, Synthesis, and Biological Activity of Novel Myricetin Derivatives Containing Amide, Thioether, and 1,3,4-Thiadiazole Moieties. Molecules, 23(12), 3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23123132