Utilization of Sodium Nitroprusside as an Intestinal Permeation Enhancer for Lipophilic Drug Absorption Improvement in the Rat Proximal Intestine

Abstract

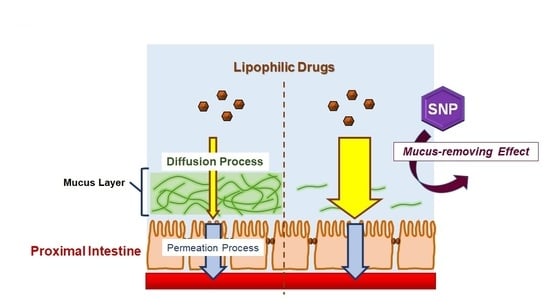

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. SNP Pretreatment in the Rat Duodenum Increased Griseofulvin Transcellular Permeability

2.2. SNP Pretreatment in the Rat Intestine Showed Regional Differences in the Absorption Enhancement Effect

2.3. SNP Showed a Mucus-Removing Effect in the Rat Intestine, Contributing to the Permeation Enhancement Effect

2.4. Assessment of the SNP Pretreatment Effect on the Intestinal Permeability of Various Lipophilic Drugs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Lipophilic Drug Intestinal Permeation Study

- dQ/dt—the flux of the test compound in the serosal side,

- C0—the initial concentration in the mucosal side,

- S—the surface area of the intestinal lumen.

4.3. Mucosal Glycoprotein Measurement

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Maher, S.; Mrsny, R.J.; Brayden, D.J. Intestinal permeation enhancers for oral peptide delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 106, 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.H.; Yamamoto, A. Penetration and enzymatic barriers to peptide and protein absorption. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1989, 4, 171–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, C. Nitric oxide as a secretory product of mammalian cells. FASEB J. 1992, 6, 3051–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utoguchi, N.; Watanabe, Y.; Shida, T.; Matsumoto, M. Nitric oxide donors enhance rectal absorption of macromolecules in rabbits. Pharm. Res. 1998, 15, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Tatsumi, H.; Maruyama, M.; Uchiyama, T.; Okada, N.; Fujita, T. Modulation of intestinal permeability by nitric oxide donors: Implications in intestinal delivery of poorly absorbable drugs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001, 296, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kishimoto, H.; Miyazaki, K.; Takizawa, Y.; Shirasaka, Y.; Inoue, K. Absorption-enhancing effect of nitric oxide on the absorption of hydrophobic drugs in rat duodenum. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.D.; Yang, L. NO donors and NO delivery methods for controlling biofilms in chronic lung infections. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 3931–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrabie, J.A.; Klose, J.R.; Wink, D.A.; Keefer, L.K. New nitric oxide-releasing zwitterions derived from polyamines. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 1472–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belani, K.G.; Hottinger, D.G.; Kozhimannil, T.; Prielipp, R.C.; Beebe, D.S. Sodium nitroprusside in 2014: A clinical concepts review. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 30, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoupa, E.; Pitsikas, N. The Nitric oxide (NO) donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) and its potential for the schizophrenia therapy: Lights and shadows. Molecules 2021, 26, 3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobias, J.D.; Tulman, D.B.; Bergese, S.D. Clevidipine for Perioperative blood pressure control in infants and children. Pharmacy 2013, 6, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grossi, L.; D’Angelo, S. Sodium nitroprusside: Mechanism of NO release mediated by sulfhydryl-containing molecules. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 2622–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, A.L.; Menconi, M.J.; Unno, N.; Ezzell, R.M.; Casey, D.M.; Gonzalez, P.K.; Fink, M.P. Nitric oxide dilates tight junctions and depletes ATP in cultured Caco-2BBe intestinal epithelial monolayers. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 1995, 268, G361–G373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takizawa, Y.; Kishimoto, H.; Kitazato, T.; Ishizaka, H.; Kamiya, N.; Ito, Y.; Tomita, M.; Hayashi, M. Characteristics of reversible absorption-enhancing effect of sodium nitroprusside in rat small intestine. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 49, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, K.; Kishimoto, H.; Muratani, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Shirasaka, Y.; Inoue, K. Mucins are involved in the intestinal permeation of lipophilic drugs in the proximal region of rat small intestine. Pharm. Res. 2019, 36, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, I.H.; Corcoran, A.C.; Dustan, H.P.; Koppanyi, T. Cardiovascular actions of sodium nitroprusside in animals and hypertensive patients. Circulation 1955, 11, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thornton, D.J.; Rousseau, K.; McGuckin, M.A. Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airways mucus. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008, 70, 459–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corfield, A.P.; Carroll, D.; Myerscough, N.; Probert, C.S. Mucins in the gastrointestinal tract in health and disease. Front. Biosci. 2001, 6, D1321–D1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, A.; Bath, J.; Jaramillo, A.M.; Ridley, C.; Walsh, A.A.; Evans, C.M.; Thornton, D.J.; Ribbeck, K. Mucus. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R938–R945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murgia, X.; Loretz, B.; Hartwig, O.; Hittinger, M.; Lehr, C.M. The role of mucus on drug transport and its potential to affect therapeutic outcomes. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 124, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, R.A. Barrier properties of mucus. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reighard, K.P.; Ehre, C.; Rushton, Z.L.; Ahonen, M.J.R.; Hill, D.B.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Role of nitric oxide-releasing chitosan oligosaccharides on mucus viscoelasticity. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 3, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahonen, M.J.R.; Hill, D.B.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Nitric oxide-releasing alginates as mucolytic agents. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 3409–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rindone, J.P.; Sloane, E.P. Cyanide toxicity from sodium nitroprusside: Risks and management. Ann. Pharmacother. 1992, 26, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimaoka, M.; Iida, T.; Ohara, A.; Taenaka, N.; Mashimo, T.; Honda, T.; Yoshiya, I. NOC, A nitric-oxide-releasing compound, induces dose-dependent apoptosis in macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 209, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Log D (pH 6.5) a | Intestinal Region | Papp (10−5 cm/s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTRL | SNP | Ratio | |||

| Griseofulvin | 2.17 | Duodenum | 0.80 ± 0.42 | 1.96 ± 0.41 ** | 2.45 |

| Jejunum | 4.22 ± 2.00 | 7.03 ± 1.92 ** | 1.67 | ||

| Ileum | 2.43 ± 0.60 | 1.84 ± 0.44 | 0.76 | ||

| Colon | 3.96 ± 2.14 | 3.17 ± 1.11 | 0.80 | ||

| Flurbiprofen | 1.50 | Duodenum | 0.58 ± 0.17 | 1.30 ± 0.27 ** | 2.24 |

| Jejunum | 2.60 ± 1.19 | 3.27 ± 1.29 | 1.26 | ||

| Ileum | 3.39 ± 1.13 | 3.98 ± 1.77 | 1.17 | ||

| Colon | 2.83 ± 0.25 | 1.94 ± 0.37 ** | 0.69 | ||

| Antipyrine | 1.22 | Duodenum | 1.37 ± 0.64 | 1.22 ± 0.36 | 0.89 |

| Jejunum | 1.96 ± 0.52 | 2.26 ± 0.45 | 1.15 | ||

| Ileum | 1.79 ± 0.40 | 2.15 ± 0.58 | 1.20 | ||

| Colon | 1.62 ± 0.38 | 1.99 ± 0.30 | 1.23 | ||

| Theophylline | −0.08 | Duodenum | 2.34 ± 0.32 | 2.80 ± 1.23 | 1.20 |

| Jejunum | 1.71 ± 1.14 | 1.67 ± 0.73 | 0.98 | ||

| Ileum | 2.37 ± 0.55 | 2.47 ± 1.36 | 1.04 | ||

| Colon | 2.07 ± 0.17 | 1.23 ± 0.25 ** | 0.59 | ||

| Propranolol | −0.32 | Duodenum | 0.11 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 1.18 |

| Jejunum | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.43 ± 0.18 | 0.91 | ||

| Ileum | 0.37 ± 0.10 | 0.39 ± 0.10 | 1.05 | ||

| Colon | 0.21 ± 0.11 | 0.35 ± 0.16 * | 1.67 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kishimoto, H.; Miyazaki, K.; Tedzuka, H.; Ozawa, R.; Kobayashi, H.; Shirasaka, Y.; Inoue, K. Utilization of Sodium Nitroprusside as an Intestinal Permeation Enhancer for Lipophilic Drug Absorption Improvement in the Rat Proximal Intestine. Molecules 2021, 26, 6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26216396

Kishimoto H, Miyazaki K, Tedzuka H, Ozawa R, Kobayashi H, Shirasaka Y, Inoue K. Utilization of Sodium Nitroprusside as an Intestinal Permeation Enhancer for Lipophilic Drug Absorption Improvement in the Rat Proximal Intestine. Molecules. 2021; 26(21):6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26216396

Chicago/Turabian StyleKishimoto, Hisanao, Kaori Miyazaki, Hiroshi Tedzuka, Ryosuke Ozawa, Hanai Kobayashi, Yoshiyuki Shirasaka, and Katsuhisa Inoue. 2021. "Utilization of Sodium Nitroprusside as an Intestinal Permeation Enhancer for Lipophilic Drug Absorption Improvement in the Rat Proximal Intestine" Molecules 26, no. 21: 6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26216396

APA StyleKishimoto, H., Miyazaki, K., Tedzuka, H., Ozawa, R., Kobayashi, H., Shirasaka, Y., & Inoue, K. (2021). Utilization of Sodium Nitroprusside as an Intestinal Permeation Enhancer for Lipophilic Drug Absorption Improvement in the Rat Proximal Intestine. Molecules, 26(21), 6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26216396