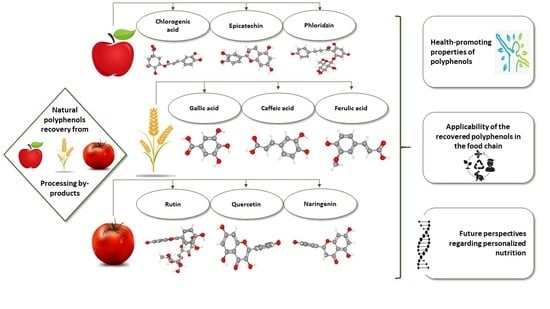

Natural Polyphenol Recovery from Apple-, Cereal-, and Tomato-Processing By-Products and Related Health-Promoting Properties

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Polyphenols in Apple-Processing By-Products

3. Polyphenols in Cereal-Processing By-Products

4. Polyphenols in Tomato-Processing By-Products

5. Health-Promoting Properties of Polyphenol-Rich Diets

5.1. The Prebiotic Potential of Phenolic Compounds

5.2. Cardioprotective Effects of Polyphenols

5.3. Polyphenols in Weight-Control Diets

6. Applicability of Recovered Polyphenols from Apple-, Cereal-, and Tomato-Processing By-Products in Functional Food Products in the Food Chain

6.1. Apple-Processing-Derived By-Products

6.2. Cereal-Processing-Derived By-Products

6.3. Tomato-Processing-Derived By-Products

| Food Product | Effect On Food Product | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | AP flour (5, 10%) | Bakery product—sourdough | + cell viability; ↑ organic acid content (malic, oxalic, and citric acid) | [3] |

| AP flour (5, 10, 15%) | Cereal crispbread | ↑ total dietary fiber; ↑ hardness and crispiness | [139] | |

| Apple peel powder | Muffin | ↑ dietary fiber; ↑ bioactive compounds; + color and texture; + organoleptic characteristics (12%) | [157] | |

| AP flour (2.5, 5, 7, 10%) | Pasta | ↓ carbohydrate content; ↑ fiber, protein, fat, and ash content; ↑ swelling index, cooking water absorption, and cooking loss; ↓ optimum cooking time; ↓ texture and structure of pasta (10%) | [32] | |

| AP (2, 3, 6, 9%) | Freeze-dried snacks | ↑ AP; ↓ lightness coefficient; ↑ cutting force; ↑ organoleptic properties (2%); ↓ water activity | [158] | |

| AP 20% | GF corn snacks | ↑x36 chlorogenic acid; ↑x4 cryptochlorogenic acid; ↑x6 catechin; ↑x3 procyanidin; ↑x8 epicatechin; ↑x25 phlorizin; ↑x3 total soluble and insoluble dietary fiber; ↑ organoleptic scores | [159] | |

| AP powder | Yogurt | ↓ sensory profile; ↑ protein and fat content; ↑ rheological attributes | [141] | |

| Freeze-dried AP powder (0.5, 1%) | Set-type yogurt | ↑ gelation pH; ↓ fermentation time (1%); firmer and consistent yogurt (cold storage); stable structure (0.5%); stabilizer and texturizer | [43] | |

| Dried AP (7, 14%) | Italian salami | ↓ fat and calories; ↑ fiber and phenol content | [140] | |

| Defatted apple seed flour | Chewing gum | ↑ phlorizin content (52–67% and 75–83% of the total phenolics) | [143] | |

| Cereal | WB & BF | Bread | ↑ dietary fibers content | [160] |

| ↑ alveograph profile | ||||

| ↑ volume of bread | ||||

| SCC (10, 20, and 30%) | GF rice muffin | ↑ dietary fibers and ferulic acid content; ↑ nutritional value; + height, color, and texture (20% SCC) | [147] | |

| BRF | Buns and muffins | ↑ dietary fibers, iron, zinc, and calcium; ↑ antioxidant capacity and phytonutrient content; ↓ carbohydrates and sensory acceptability; moderate glycemic index and glycemic load; ↑ shelf life | [161] | |

| OPC & OPI | Yogurt | ↑ nutritional benefits (OPI); ↑ product quality and sustainability (OPC); ↑ nutritional (OPC) | [149] | |

| BMG + PBD (1:1) | Cereal composite bar | + essential minerals and fiber; ↑ sensorial evaluation; antifungal properties | [162] | |

| BSG | Yogurt | ↑ viscosity and shear stress; ↓ fermentation time; maintained flow behavior and stability | [163] | |

| BRG+PFPF+WP | GF breakfast cereals | Average acceptance; + total, soluble, and insoluble dietary fiber; ↑ darkness, protein, and carbohydrate content; ↓ expansion and consumer acceptance | [164] | |

| PH | Gel-based foods | ↑ textural and sensory characteristics; syneresis and fat loss during cooking avoidance; ↑ gelling properties | [165] | |

| Tomato | CT | Hemp, flaxseed, grapeseed oil | ↑ oil quality; ↑ viscosity (flaxseed oil); ↓ viscosity (hemp and grapeseed oil); intense color | [154] |

| TBPP | biofilms | ↑ aesthetic impact and coloring; ↓ transparency | [166] | |

| TBPP | biofilms | ↑ physical properties (diameter, thickness, density, weight); ↑ antimicrobial effect; ↑ total phenolic content | [155] | |

| TPP | GF ready to cook snack | ↑ fiber, mineral, and lycopene content; ↑ antioxidant activity; ↓ oil uptake | [167] | |

| TPF | Spreadable cheese | ↑ spreadability; ↑ antioxidant activity and phenolic content; ↑ fibers | [168] | |

| TBP | Passata | ↑ total dietary fiber; ↑ lycopene and polyphenols | [169] | |

| TPP (5, 10, 15, 20, 25%) | cookies | ↓ lightness values; ↑ redness and yellowness; acceptable by consumers (5%) | [170] | |

| TPF (15%) | pasta | ↑ carotenoids and dietary fiber; ↓ sensory scores for elasticity, odor, and firmness | [171] |

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Gu, B.; Zhang, X.; Bai, X.; Fu, B.; Chen, D. Four steps to food security for swelling cities. Nature 2019, 566, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, K.; Teleky, E.B.; Ranga, F.; Simon, E.; Pop, L.O.; Babalau-Fuss, V.; Kapsalis, N.; Cristian, D. Bioaccessibility of microencapsulated carotenoids, recovered from tomato processing industrial by-products, using in vitro digestion model. LWT 2021, 152, 112285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martău, G.A.; Teleky, B.E.; Ranga, F.; Pop, I.D.; Vodnar, D.C. Apple Pomace as a Sustainable Substrate in Sourdough Fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iriondo-Dehond, M.; Miguel, E.; Del Castillo, M.D. Food byproducts as sustainable ingredients for innovative and healthy dairy foods. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Available online: https://www.fao.org/home/en (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Zhang, R.; Ma, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, M.; Tian, S.; Wang, D.; Liu, K.; Liu, H.; Zhu, W.; Wang, X. Grain & Oil Science and Technology Comprehensive utilization of corn starch processing by-products: A review. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 2021, 4, 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Deroover, L.; Tie, Y.; Verspreet, J.; Courtin, C.M.; Verbeke, K. Modifying wheat bran to improve its health benefits. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1104–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fărcaș, A.C.; Socaci, S.A.; Nemeș, S.A.; Pop, O.L.; Coldea, T.E.; Fogarasi, M.; Biriș-Dorhoi, E.S. An Update Regarding the Bioactive Compound of Cereal By-Products: Health Benefits and Potential Applications. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, V.; Chrysafi, A.; Lamminen, M.; Troell, M.; Jalava, M.; Piipponen, J.; Siebert, S.; Van Hal, O.; Virkki, V.; Kummu, M. Food system by-products upcycled in livestock and aquaculture feeds can increase global food supply. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodnar, D.C.; Calinoiub, L.F.; Mitrea, L.; Precup, G.; Bindea, M.; Pacurar, A.M.; Szabo, K.; Stefanescu, B.E. A New Generation of Probiotic Functional Beverages Using Bioactive Compounds from Agro-Industrial Waste; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780128163979. [Google Scholar]

- Călinoiu, L.F.; Vodnar, D.C. Thermal processing for the release of phenolic compounds from wheat and oat bran. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Călinoiu, L.F.; Vodnar, D.C. Whole Grains and Phenolic Acids: A Review on Bioactivity, Functionality, Health Benefits and Bioavailability. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martău, G.A.; Unger, P.; Schneider, R.; Venus, J.; Vodnar, D.C.; López-Gómez, J.P. Integration of solid state and submerged fermentations for the valorization of organic municipal solid waste. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florina, L.; Adriana-florinela, C.; Vodnar, D.C. Solid-State Yeast Fermented Wheat and Oat Bran as A Route for Delivery of Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Purić, M.; Rabrenović, B.; Rac, V.; Pezo, L.; Tomašević, I.; Demin, M. Application of defatted apple seed cakes as a by-product for the enrichment of wheat bread. LWT 2020, 130, 109391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spengler, R.N. Origins of the apple: The role of megafaunal mutualism in the domestication of Malus and rosaceous trees. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giovanetti Canteri, M.H.; Nogueira, A.; de Oliveira Petkowicz, C.L.; Wosiacki, G. Characterization of Apple Pectin—A Chromatographic Approach. Chromatogr. Most Versatile Method Chem. Anal. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Wang, L.; Huber, G.M.; Pitts, N.L. Effect of baking on dietary fibre and phenolics of muffins incorporated with apple skin powder. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabetafika, H.N.; Bchir, B.; Blecker, C.; Richel, A. Fractionation of apple by-products as source of new ingredients: Current situation and perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 40, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, T.; Costa, A.; Faria-Silva, C.; Ribeiro, D.; Ferreira, M.P.; Sim, S.; Ascenso, A. Sustainable Valorization of Tomato By-Products to Obtain Bioactive Compounds: Their Potential in Inflammation and Cancer Management. Molecules 2022, 27, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Hyun, S.; Keum, Y. An updated review on use of tomato pomace and crustacean processing waste to recover commercially vital carotenoids. Food Res. Int. 2018, 108, 516–529. [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, K.; Cătoi, A.-F.; Vodnar, D.C. Bioactive Compounds Extracted from Tomato Processing by-Products as a Source of Valuable Nutrients. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2018, 73, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strati, I.F.; Oreopoulou, V. Recovery of carotenoids from tomato processing by-products—A review. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, G.; Wu, L. Recent advances in the effects of dietary polyphenols on inflammation in vivo: Potential molecular mechanisms, receptor targets, safety issues, and uses of nanodelivery system and polyphenol polymers. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 48, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plamada, D.; Vodnar, D.C. Polyphenols—Gut Microbiota Interrelationship: A Transition to a New Generation of Prebiotics. Nutrients 2022, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, N.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Wastes and by-products: Upcoming sources of carotenoids for biotechnological purposes and health-related applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 62, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Morozova, K.; Scampicchio, M.; Ferrentino, G. Non-Extractable polyphenols from food by-products: Current knowledge on recovery, characterisation, and potential applications. Processes 2020, 8, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čolović, D.; Rakita, S.; Banjac, V.; Đuragić, O.; Čabarkapa, I. Plant food by-products as feed: Characteristics, possibilities, environmental benefits, and negative sides. Food Rev. Int. 2019, 35, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Precup, G.; Mitrea, L.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Martău, A.G.; Nemeş, A.; Emoke Teleky, B.; Coman, V.; Vodnar, D.C. Food processing by-products and molecular gastronomy. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 8, 137–163. [Google Scholar]

- Coman, V.; Teleky, B.-E.; Mitrea, L.; Martău, G.A.; Szabo, K.; Călinoiu, L.-F.; Vodnar, D.C. Bioactive Potential of Fruit and Vegetable Wastes; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 91, ISBN 9780128204702. [Google Scholar]

- Francini, A.; Sebastiani, L. Phenolic compounds in apple (Malus x domestica borkh.): Compounds characterization and stability during postharvest and after processing. Antioxidants 2013, 2, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bchir, B.; Karoui, R.; Danthine, S.; Blecker, C.; Besbes, S.; Attia, H. Date, Apple, and Pear By-Products as Functional Ingredients in Pasta: Cooking Quality Attributes and Physicochemical, Rheological, and Sensorial Properties. Foods 2022, 11, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołębiewska, E.; Kalinowska, M.; Yildiz, G. Sustainable Use of Apple Pomace (AP) in Different Industrial Sectors. Materials 2022, 15, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.; Luiz, S.F.; Azeredo, D.R.P.; Cruz, A.G.; Ajlouni, S.; Ranadheera, C.S. Apple pomace as a functional and healthy ingredient in food products: A review. Processes 2020, 8, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ricci, A.; Cirlini, M.; Guido, A.; Liberatore, C.M.; Ganino, T.; Lazzi, C.; Chiancone, B. From byproduct to resource: Fermented apple pomace as beer flavoring. Foods 2019, 8, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Le Deun, E.; Van Der Werf, R.; Le Bail, G.; Le Quéré, J.M.; Guyot, S. HPLC-DAD-MS Profiling of Polyphenols Responsible for the Yellow-Orange Color in Apple Juices of Different French Cider Apple Varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7675–7684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinuevo-Salces, B.; Riaño, B.; Hijosa-Valsero, M.; González-García, I.; Paniagua-García, A.I.; Hernández, D.; Garita-Cambronero, J.; Díez-Antolínez, R.; García-González, M.C. Valorization of apple pomaces for biofuel production: A biorefinery approach. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 142, 105785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaosadati, S.A.; Babaeipour, V. Citric acid production from apple pomace in multi-layer packed bed solid-state bioreactor. Process Biochem. 2002, 37, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.F.; Vieira, R.G.; Zardo, D.M.; Falcão, L.D.; Nogueira, A.; Wosiacki, G. Apple pomace from eleven cultivars: An approach to identify sources of bioactive compounds. Acta Sci. Agron. 2010, 32, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzak-Drozd, K.; Oniszczuk, T.; Stasiak, M.; Oniszczuk, A. Beneficial effects of phenolic compounds on gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergent, T.; Piront, N.; Meurice, J.; Toussaint, O.; Schneider, Y.J. Anti-inflammatory effects of dietary phenolic compounds in an in vitro model of inflamed human intestinal epithelium. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 188, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, R.C.; Gigliotti, J.C.; Ku, K.M.; Tou, J.C. A comprehensive analysis of the composition, health benefits, and safety of apple pomace. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 893–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kristo, E.; LaPointe, G. The effect of apple pomace on the texture, rheology and microstructure of set type yogurt. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 91, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumul, D.; Ziobro, R.; Korus, J.; Kruczek, M. Apple pomace as a source of bioactive polyphenol compounds in gluten-free breads. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walia, M.; Rawat, K.; Bhushan, S.; Padwad, Y.S.; Singh, B. Fatty acid composition, physicochemical properties, antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of apple seed oil obtained from apple pomace. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolarinwa, I.F.; Orfila, C.; Morgan, M.R.A. Determination of amygdalin in apple seeds, fresh apples and processed apple juices. Food Chem. 2015, 170, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Opyd, P.M.; Jurgoński, A.; Juśkiewicz, J.; Milala, J.; Zduńczyk, Z.; Król, B. Nutritional and health-related effects of a diet containing apple seed meal in rats: The case of amygdalin. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Montañés, F.; Catchpole, O.J.; Tallon, S.; Mitchell, K.A.; Scott, D.; Webby, R.F. Extraction of apple seed oil by supercritical carbon dioxide at pressures up to 1300 bar. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 141, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Yi, J.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Bi, J. Systematic Review of Phenolic Compounds in Apple Fruits: Compositions, Distribution, Absorption, Metabolism, and Processing Stability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollini, L.; Cossignani, L.; Juan, C.; Mañes, J. Extraction of phenolic compounds from fresh apple pomace by different non-conventional techniques. Molecules 2021, 26, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelli, V.; Corti, S. Phloridzin and other phytochemicals in apple pomace: Stability evaluation upon dehydration and storage of dried product. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 1578–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrubá, M.; Baxant, J.; Čížková, H.; Smutná, V.; Kovařík, F.; Ševčík, R.; Hanušová, K.; Rajchl, A. Phloridzin as a marker for evaluation of fruit product’s authenticity. Czech J. Food Sci. 2021, 39, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Gupta, S.; Rana, A.; Bhushan, S. Functional properties, phenolic constituents and antioxidant potential of industrial apple pomace for utilization as active food ingredient. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2015, 4, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Táborský, J.; Sus, J.; Lachman, J.; Šebková, B.; Adamcová, A.; Šatínský, D. Dynamics of phloridzin and related compounds in four cultivars of apple trees during the vegetation period. Molecules 2021, 26, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafian, M.; Jahromi, M.Z.; Nowroznejhad, M.J.; Khajeaian, P.; Kargar, M.M.; Sadeghi, M.; Arasteh, A. Phloridzin reduces blood glucose levels and improves lipids metabolism in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 5299–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamdi, S.P.; Badwaik, H.R.; Raval, A.; Ajazuddin; Nakhate, K.T. Ameliorative potential of phloridzin in type 2 diabetes-induced memory deficits in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 913, 174645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masumoto, S.; Akimoto, Y.; Oike, H.; Kobori, M. Dietary Phloridzin Reduces Blood Glucose Levels and Reverses Sglt1 Expression in the Small Intestine in Streptozotocin-lnduced Diabetic Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 4651–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.Y.; Liang, J.; Chen, S.X.; Wang, B.X.; Yuan, H.; Li, C.T.; Wu, Y.Y.; Wu, Y.F.; Shi, X.G.; Gao, J.; et al. Phloridzin alleviate colitis in mice by protecting the intestinal brush border and improving the expression of sodium glycogen transporter 1. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 45, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.Z.; Yang, S.; Wu, G. Free radicals, antioxidants, and nutrition. Nutrition 2002, 18, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.; Mohan Rao, L.J. An Outlook on Chlorogenic Acids-Occurrence, Chemistry, Technology, and Biological Activities. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 968–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropley, V.; Croft, R.; Silber, B.; Neale, C.; Scholey, A.; Stough, C.; Schmitt, J. Does coffee enriched with chlorogenic acids improve mood and cognition after acute administration in healthy elderly? A pilot study. Psychopharmacology 2012, 219, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, A.; Catherine, P.B.; Liu, A.H.; Considine, M.J.; Rich, L.; Mas, E.; Croft, K.D.; Hodgson, J.M. Acute effects of chlorogenic acid on nitric oxide status, endothelial function and blood pressure in healthy volunteers: A randomised trial. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9130–9136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Liu, A.; Li, P.; Liu, C.; Xiao, W.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S. Advances in physiological functions and mechanisms of (-)-epicatechin. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilleros, D.Á.; Martín, M.Á.; Ramos, S. (−)-Epicatechin and the colonic 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid metabolite regulate glucose uptake, glucose production, and improve insulin signalling in renal NRK-52E cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1700470. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Herrera, I.; Chen, X.; Ramos, S.; Devaraj, S. (−)-Epicatechin attenuates high-glucose-induced inflammation by epigenetic modulation in human monocytes. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luithui, Y.; Baghya Nisha, R.; Meera, M.S. Cereal by-products as an important functional ingredient: Effect of processing. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fărcaș, A.; Drețcanu, G.; Pop, T.D.; Enaru, B.; Socaci, S.; Diaconeasa, Z. Cereal processing by-products as rich sources of phenolic compounds and their potential bioactivities. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roasa, J.; De Villa, R.; Mine, Y.; Tsao, R. Phenolics of cereal, pulse and oilseed processing by-products and potential effects of solid-state fermentation on their bioaccessibility, bioavailability and health benefits: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 954–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylewicz, U.; Nowacka, M.; Martín-García, B.; Wiktor, A.; Gómez Caravaca, A.M. Target Sources of Polyphenols in Different Food Products and Their Processing By-Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 9780128135723. [Google Scholar]

- Apprich, S.; Tirpanalan, Ö.; Hell, J.; Reisinger, M.; Böhmdorfer, S.; Siebenhandl-Ehn, S.; Novalin, S.; Kneifel, W. Wheat bran-based biorefinery 2: Valorization of products. LWT 2014, 56, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannikova, A.; Zyainitdinov, D.; Evteev, A.; Drevko, Y.; Evdokimov, I. Microencapsulation of polyphenols and xylooligosaccharides from oat bran in whey protein-maltodextrin complex coacervates: In-vitro evaluation and controlled release. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2020, 23, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Yin, T.; Han, W.; Zhang, X. Nutritional Ingredients and Active Compositions of Defatted Rice Bran; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780128128282. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, M.P.; Moreau, R.A.; Hicks, K.B. Phenolic acids, lipids, and proteins associated with purified corn fiber arabinoxylans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moongngarm, A.; Daomukda, N.; Khumpika, S. Chemical Compositions, Phytochemicals, and Antioxidant Capacity of Rice Bran, Rice Bran Layer, and Rice Germ. APCBEE Procedia 2012, 2, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yue, Z.; Sun, L.L.; Sun, S.N.; Cao, X.F.; Wen, J.L.; Zhu, M.Q. Structure of corn bran hemicelluloses isolated with aqueous ethanol solutions and their potential to produce furfural. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 288, 119420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Wang, L.; Shao, P.; Lu, B.; Chen, Y.; Sun, P. Simultaneous analysis of free phytosterols and phytosterol glycosides in rice bran by SPE/GC–MS. Food Chem. 2022, 387, 132742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duţă, D.E.; Culeţu, A.; Mohan, G. Reutilization of Cereal Processing By-Products in Bread Making; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2018; ISBN 9780081022146. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, R.A.; Hicks, K.B. The composition of corn oil obtained by the alcohol extraction of ground corn. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2005, 82, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzami, A.N.; Ho, T.M.; Mikkonen, K.S. Valorization of cereal by-product hemicelluloses: Fractionation and purity considerations. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 110818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, E.; Nordberg Karlsson, E.; Adlercreutz, P. Warming weather changes the chemical composition of oat hulls. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Chen, H.; Cheng, W.; Yang, K.; Cai, L.; He, L.; Du, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, A.; Zeng, Z.; et al. Impact of arabinoxylan on characteristics, stability and lipid oxidation of oil-in-water emulsions: Arabinoxylan from wheat bran, corn bran, rice bran, and rye bran. Food Chem. 2021, 358, 129813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndolo, V.U.; Beta, T. Comparative studies on composition and distribution of phenolic acids in cereal grain botanical fractions. Cereal Chem. 2014, 91, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Diana, A.B.; García-Casas, M.J.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Frías, J.; Peñas, E.; Rico, D. Wheat and oat brans as sources of polyphenol compounds for development of antioxidant nutraceutical ingredients. Foods 2021, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.N.; Wu, W.J.; Sun, C.Z.; Liu, H.F.; Chen, W.B.; Zhan, Q.P.; Lei, Z.G.; Xin, X.; Ma, J.J.; Yao, K.; et al. Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Capacity of Ferulic Acid Released from Wheat Bran by Solid-state Fermentation of Aspergillus niger. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2019, 32, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Long, L.; Wu, L.; Lin, Q.; Ding, S. Highly Efficient Extraction of Ferulic Acid from Cereal Brans by a New Type A Feruloyl Esterase from Eupenicillium parvum in Combination with Dilute Phosphoric Acid Pretreatment. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 190, 1561–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.; Singh, N.K.; Tupe, R.; Odenath, A.; Lali, A. Biotransformation of corn bran derived ferulic acid to vanillic acid using engineered Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 50, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed Nignpense, B.; Francis, N.; Blanchard, C.; Santhakumar, A.B. Bioaccessibility and bioactivity of cereal polyphenols: A review. Foods 2021, 10, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martău, G.A.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Vodnar, D.C. Bio-vanillin: Towards a sustainable industrial production. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boz, H. p-Coumaric acid in cereals: Presence, antioxidant and antimicrobial effects. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 2323–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosele, J.I.; Macià, A.; Motilva, M.J. Metabolic and microbial modulation of the large intestine ecosystem by non-absorbed diet phenolic compounds: A review. Molecules 2015, 20, 17429–17468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anson, N.M.; Aura, A.M.; Selinheimo, E.; Mattila, I.; Poutanen, K.; Van Den Berg, R.; Havenaar, R.; Bast, A.; Haenen, G.R.M.M. Bioprocessing of wheat bran in whole wheat bread increases the bioavailability of phenolic acids in men and exerts antiinflammatory effects ex vivo1-3. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamadou, M.; Martin Alain, M.M.; Obadias, F.V.; Hashmi, M.Z.; Başaran, B.; Jean Paul, B.; Samuel René, M. Consumption of underutilised grain legumes and the prevention of type II diabetes and cardiometabolic diseases: Evidence from field investigation and physicochemical analyses. Environ. Chall. 2022, 9, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumrungpert, A.; Lilitchan, S.; Tuntipopipat, S.; Tirawanchai, N.; Komindr, S. Ferulic acid supplementation improves lipid profiles, oxidative stress, and inflammatory status in hyperlipidemic subjects: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Kaul, P. Evaluation of tomato processing by-products: A comparative study in a pilot scale setup. J. Food Process Eng. 2014, 37, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, K.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Cătoi, A.-F.; Vodnar, D.C. Screening of ten tomato varieties processing waste for bioactive components and their related antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schieber, A. By-Products of Plant Food Processing as a Source of Valuable Compounds. Ref. Modul. Food Sci. 2019, 12, 401–413. [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, K.; Dulf, F.V.; Eleni, P.; Boukouvalas, C.; Krokida, M.; Kapsalis, N.; Rusu, A.V.; Socol, C.T.; Vodnar, D.C. Evaluation of the Bioactive Compounds Found in Tomato Seed Oil and Tomato Peels Influenced by Industrial Heat Treatments. Foods 2021, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, M.; Iancu, P.; Plesu, V.; Todasca, M.C.; Isopencu, G.O.; Bildea, C.S. Valuable Natural Antioxidant Products Recovered from Tomatoes by Green Extraction. Molecules 2022, 27, 4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, K.; Dulf, F.V.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Vodnar, D.C. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of tomato processing byproducts and their correlation with the biochemical composition. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 116, 108558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Carrión, Á.; Calani, L.; de Azua, M.J.R.; Mena, P.; Del Rio, D.; Suárez, M.; Arola-Arnal, A. (Poly)phenolic composition of tomatoes from different growing locations and their absorption in rats: A comparative study. Food Chem. 2022, 388, 132984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Varatharajan, V.; Oh, W.Y.; Peng, H. Phenolic compounds in agri-food by-products, their bioavailability and health effects. J. Food Bioact. 2019, 5, 57–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ebrahimi, P.; Lante, A. Environmentally Friendly Techniques for the Recovery of Polyphenols from Food By-Products and Their Impact on Polyphenol Oxidase: A Critical Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shixian, Q.; Dai, Y.; Kakuda, Y.; Shi, J.; Mittal, G.; Yeung, D.; Jiang, Y. Synergistic anti-oxidative effects of lycopene with other bioactive compounds. Food Rev. Int. 2005, 21, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, H.; Santos, D.; Campos, D.A.; Ratinho, M.; Rodrigues, I.M.; Pintado, M.E. Development of Frozen Pulps and Powders from Carrot and Tomato by-Products: Impact of Processing and Storage Time on Bioactive and Biological Properties. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-González, I.; García-Valverde, V.; García-Alonso, J.; Periago, M.J. Chemical profile, functional and antioxidant properties of tomato peel fiber. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1528–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, F.; Sanmartin, C.; Taglieri, I.; Andrich, G.; Zinnai, A. A simplified method to estimate Sc-CO2 extraction of bioactive compounds from different matrices: Chili pepper vs. tomato by-products. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Tsao, R. Dietary polyphenols, oxidative stress and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016, 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daglia, M. Polyphenols as antimicrobial agents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo-Rodrigues, H.; Santos, D.; Campos, D.A.; Guerreiro, S.; Ratinho, M.; Rodrigues, I.M.; Pintado, M.E. Impact of processing approach and storage time on bioactive and biological properties of rocket, spinach and watercress byproducts. Foods 2021, 10, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, S.; Mitrea, L.; Adrian, G.; Szabo, K.; Mihai, M.; Vodnar, D.C.; Cris, G. Microencapsulation and Bioaccessibility of Phenolic Compounds of Vaccinium Leaf Extracts. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 674. [Google Scholar]

- Petroff, O.A.C. Book Review: GABA and Glutamate in the Human Brain. Neurosci. 2002, 8, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattern, H.P.D.; Del Bo, C.; Bernardi, S.; Marino, M.; Porrini, M.; Tucci, M.; Guglielmetti, S.; Cherubini, A.; Carrieri, B.; Kirkup, B.; et al. Systematic Review on Polyphenol Intake and Health Outcomes: Is there Su ffi cient Evidence to define a health-promoting polyphenol-rich dietary pattern. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1355. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Polyphenol-Rich Dry Common Beans ( Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and Their Health Benefits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitrea, L.; Nemes, S.-A.; Szabo, K.; Teleky, B.-E.; Vodnar, D.-C. Guts Imbalance Imbalances the Brain: A Review of Gut Microbiota Association with Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 813204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condezo-hoyos, L.; Gazi, C.; Jara, P. Design of polyphenol-rich diets in clinical trials: A systematic review. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, H.; Triebel, S.; Kahle, K.; Richling, E. The Metabolic Fate of Apple Polyphenols in Humans. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2010, 6, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, J.C.M.; Arraibi, A.A.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Bioactive and functional compounds in apple pomace from juice and cider manufacturing: Potential use in dermal formulations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 90, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, P. Van Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition Phenolic compounds of cereals and their antioxidant capacity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 56, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenzi, E.; Novelli, B.; Okoshi, K.; Politi, M.; Paulino, B.; Muzio, D.; Guimara, J.F.C. Influence of rutin treatment on biochemical alterations in experimental diabetes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2010, 64, 214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Elbadrawy, E.; Sello, A. Evaluation of nutritional value and antioxidant activity of tomato peel extracts. Arab. J. Chem. 2011, 9, S1010–S1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Souza, E.L.; Mariano, T.; De Albuquerque, R. Potential interactions among phenolic compounds and probiotics for mutual boosting of their health- promoting properties and food functionalities—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1645–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, M.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Anne, S.; Palanisamy, U.D. Trends in Food Science & Technology Prebiotic potential of polyphenols, its effect on gut microbiota and anthropometric / clinical markers: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 634–649. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco-Ordaz, R.; Wall-Medrano, A.; Goñi, M.G.; Ramos-Clamont-Montfort, G.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Effect of phenolic compounds on the growth of selected probiotic and pathogenic bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 66, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; De Angelis, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Polo, A.; Rizzello, C.G. The sourdough fermentation is the powerful process to exploit the potential of legumes, pseudo-cereals and milling by-products in baking industry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2158–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiga, M.; Wang, D.W.; Han, Y.; Lewis, D.B.; Wu, J.C. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: From basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodnar, D.C.; Mitrea, L.; Teleky, B.E.; Szabo, K.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Nemeş, S.A.; Martău, G.A. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Caused by (SARS-CoV-2) Infections: A Real Challenge for Human Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 575559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y. Comparative study on the effects of apple peel polyphenols and apple flesh polyphenols on cardiovascular risk factors in mice. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2017, 40, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, A. Anti-hypertensive Effect of Cereal Antioxidant Ferulic Acid and Its Mechanism of Action. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Chandran, D.; Tomar, M.; Bhuyan, D.J.; Grasso, S.; Sá, A.G.A.; Carciofi, B.A.M.; Dhumal, S.; Singh, S.; Senapathy, M.; et al. Valorization Potential of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Seed: Nutraceutical Quality, Food Properties, Safety Aspects, and Application as a Health-Promoting Ingredient in Foods. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, F.; Gotteland, M.; Gauthier, L.; Zazueta, A.; Pesoa, S.; Navarrete, P.; Balamurugan, R. The firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio: A relevant marker of gut dysbiosis in obese patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastmanesh, R. Chemico-Biological Interactions High polyphenol, low probiotic diet for weight loss because of intestinal microbiota interaction. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2011, 189, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. Cereal bran fortified-functional foods for obesity and diabetes management: Triumphs, hurdles and possibilities. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 14, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapčević-Hadnadev, T.; Hadnadev, M.; Pojić, M. The Healthy Components of Cereal By-Products and Their Functional Properties; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2018; ISBN 9780081022146. [Google Scholar]

- Precup, G.; Pocol, C.B. Awareness, Knowledge, and Interest about Prebiotics—A Study among Romanian Consumers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, S.; Ryan, L. Impact of polyphenol-rich sources on acute postprandial glycaemia: A systematic review. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, N.; Ktenioudaki, A.; Smyth, T.P.; McLoughlin, P.; Doran, L.; Auty, M.A.E.; Arendt, E.; Gallagher, E. Physicochemical assessment of two fruit by-products as functional ingredients: Apple and orange pomace. J. Food Eng. 2015, 153, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaqaband, S.; Dar, A.H.; Patel, U.; Kumar, N.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Kumar, P.; Pandey, V.K.; Kovács, B. Utilization of Fruit Seed-Based Bioactive Compounds for Formulating the Nutraceuticals and Functional Food: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 902554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, M.V.; Fărcaş, A.C.; Medeleanu, M.; Salanţă, L.C.; Borşa, A. A Sustainable Approach for the Development of Innovative Products from Fruit and Vegetable By-Products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrade, D.; Klava, D.; Gramatina, I. Cereal Crispbread Improvement with Dietary Fibre from Apple By-Products. CBU Int. Conf. Proc. 2017, 5, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grispoldi, L.; Ianni, F.; Blasi, F.; Pollini, L.; Crotti, S.; Cruciani, D.; Cenci-Goga, B.T.; Cossignani, L. Apple Pomace as Valuable Food Ingredient for Enhancing Nutritional and Antioxidant Properties of Italian Salami. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Ali, A.; Sarfraz, A.; Hong, Q.; Boran, H. Effect of Freeze-Drying on Apple Pomace and Pomegranate Peel Powders Used as a Source of Bioactive Ingredients for the Development of Functional Yogurt. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 3327401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwacka, M.; Ciurzyńska, A.; Galus, S.; Janowicz, M. Freeze-dried snacks obtained from frozen vegetable by-products and apple pomace—Selected properties, energy consumption and carbon footprint. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 77, 102949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, R.; Palabiyik, I.; Toker, O.S.; Konar, N.; Kurultay, S. Incorporation of defatted apple seeds in chewing gum system and phloridzin dissolution kinetics. J. Food Eng. 2019, 255, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.K.; Ferreira, J.A.; Sirohi, R.; Sarsaiya, S.; Khoshnevisan, B.; Baladi, S.; Sindhu, R.; Binod, P.; Pandey, A.; Juneja, A.; et al. A critical review on the development stage of biorefinery systems towards the management of apple processing-derived waste. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antioxidants, P.; Mitrea, L.; Plamada, D.; Nemes, S.A.; Lavinia-Florina, C.; Pascuta, M.S.; Varvara, R.; Szabo, K. Development of Pectin and Poly ( vinyl alcohol ) -Based Active Packaging Enriched with Itaconic Acid and Apple. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1729. [Google Scholar]

- Majzoobi, M.; Poor, Z.V.; Jamalian, J.; Farahnaky, A. Improvement of the quality of gluten-free sponge cake using different levels and particle sizes of carrot pomace powder. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, T.; Clayton, T.; Harbourne, N.; Rodriguez-Garcia, J.; Oruna-Concha, M.J. Sweet corn cob as a functional ingredient in bakery products. Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Sehrawat, R.; Kong, Y. Oat proteins: A perspective on functional properties. LWT 2021, 152, 112307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brückner-Gühmann, M.; Benthin, A.; Drusch, S. Enrichment of yoghurt with oat protein fractions: Structure formation, textural properties and sensory evaluation. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 86, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.S.; Adriana, P.; Man, S.M.; Vodnar, D.C.; Teleky, B.; Pop, C.R.; Stan, L.; Borsai, O.; Kadar, C.B.; Urcan, A.C. Quinoa Sourdough Fermented with Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 8014 Designed for Gluten-Free Muffins—A Powerful Tool to Enhance Bioactive Compounds. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verni, M.; Rizzello, C.G.; Coda, R. Fermentation biotechnology applied to cereal industry by-products: Nutritional and functional insights. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teleky, B.E.; Martău, G.A.; Ranga, F.; Pop, I.D.; Vodnar, D.C. Biofunctional soy-based sourdough for improved rheological properties during storage. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.K.; Canene-Adams, K.; Lindshield, B.L.; Boileau, T.W.-M.; Clinton, S.K.; Erdman, J.W.J. Tomato phytochemicals and prostate cancer risk. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 3486S–3492S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szabo, K.; Teleky, B.; Ranga, F.; Roman, I.; Khaoula, H.; Boudaya, E.; Ltaief, A.B.; Aouani, W.; Thiamrat, M.; Vodnar, D.C. Carotenoid Recovery from Tomato Processing By-Products through Green Chemistry. Molecules 2022, 27, 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, K.; Teleky, B.E.; Mitrea, L.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Martău, G.A.; Simon, E.; Varvara, R.A.; Vodnar, D.C. Active packaging-poly (vinyl alcohol) films enriched with tomato by-products extract. Coatings 2020, 10, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- PA Silva, Y.; Borba, B.C.; Pereira, V.A.; Reis, M.G.; Caliari, M.; Brooks, M.S.L.; Ferreira, T.A. Characterization of tomato processing by-product for use as a potential functional food ingredient: Nutritional composition, antioxidant activity and bioactive compounds. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Kaur, M.; Kaur, H. Apple peel as a source of dietary fiber and antioxidants: Effect on batter rheology and nutritional composition, textural and sensory quality attributes of muffins. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 2411–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurzyńska, A.; Popkowicz, P.; Galus, S.; Janowicz, M. Innovative Freeze-Dried Snacks with Sodium Alginate and Fruit Pomace (Only Apple or Only Chokeberry) Obtained within the Framework of Sustainable Production. Molecules 2022, 27, 3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumul, D.; Ziobro, R.; Kruczek, M.; Rosicka-Kaczmarek, J. Fruit Waste as a Matrix of Health-Promoting Compounds in the Production of Corn Snacks. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2022, 7341118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaari, F.; Zouari-Ellouzi, S.; Belguith-Fendri, L.; Yosra, M.; Ellouz-Chaabouni, S.; Ellouz-Ghorbel, R. Valorization of Cereal by Products Extracted Fibre and Potential use in Breadmaking. Chem. Afr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhai, M.D.; Hymavathi, T.V.; Kuna, A.; Mulinti, S.; Voliveru, S.R. Quality assessment of nutri-cereal bran rich fraction enriched buns and muffins. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 2231–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojah, E.Y.; Badr, A.N.; Mohamed, D.A.; Abdel-Razek, A.G. Bioactives of Pomegranate By-Products and Barley Malt Grass Engage in Cereal Composite Bar to Achieve Antimycotic and Anti-Aflatoxigenic Attributes. Foods 2022, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naibaho, J.; Butula, N.; Jonuzi, E.; Korzeniowska, M.; Laaksonen, O.; Föste, M.; Kütt, M.L.; Yang, B. Potential of brewers’ spent grain in yogurt fermentation and evaluation of its impact in rheological behaviour, consistency, microstructural properties and acidity profile during the refrigerated storage. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 125, 107412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso dos Santos, P.; Caliari, M.; Soares Soares Júnior, M.; Soares Silva, K.; Fleury Viana, L.; Gonçalves Caixeta Garcia, L.; Siqueira de Lima, M. Use of agricultural by-products in extruded gluten-free breakfast cereals. Food Chem. 2019, 297, 124956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguerol, A.T.; Marta Igual, M.; Pagán, M.J. Developing psyllium fibre gel-based foods: Physicochemical, nutritional, optical and mechanical properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 122, 107108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrea, L.; Călinoiu, L.-F.F.; Martău, G.-A.; Szabo, K.; Teleky, B.-E.E.; Mureșan, V.; Rusu, A.-V.V.; Socol, C.-T.T.; Vodnar, D.-C.C.; Mărtau, G.A.; et al. Poly(vinyl alcohol)-based biofilms plasticized with polyols and colored with pigments extracted from tomato by-products. Polymers 2020, 12, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rehal, J.K.; Aggarwal, P.; Dhaliwal, I.; Sharma, M.; Kaushik, P. A Tomato Pomace Enriched Gluten-Free Ready-to-Cook Snack’s Nutritional Profile, Quality, and Shelf Life Evaluation. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucera, A.; Costa, C.; Marinelli, V.; Saccotelli, M.A.; Alessandro, M.; Nobile, D.; Conte, A. Fruit and Vegetable By-Products to Fortify Spreadable Cheese. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sandei, L.; Stingone, C.; Vitelli, R.; Cocconi, E.; Zanotti, A.; Zoni, C. Processing tomato by-products re-use, secondary raw material for tomato product with new functionality. Acta Hortic. 2019, 1233, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Bhat, M.; Ahsan, H. Physico-Chemical Characteristics of Cookies Prepared with Tomato Pomace Powder. J. Food Process. Technol. 2016, 7, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padalino, L.; Conte, A.; Lecce, L.; Likyova, D.; Sicari, V.; Pellicanò, T.M.; Poiana, M.; Del Nobile, M.A. Functional pasta with tomato by-product as a source of antioxidant compounds and dietary fibre. Czech J. Food Sci. 2017, 35, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dankar, I.; Haddarah, A.; Omar, F.E.; Sepulcre, F.; Pujolà, M. 3D printing technology: The new era for food customization and elaboration. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 75, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrawat, N.; Yadav, M.; Singh, M.; Kumar, V.; Ruchi, V. Seminars in Cancer Biology Probiotics in microbiome ecological balance providing a therapeutic window against cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 70, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varvara, R.A.; Szabo, K.; Vodnar, D.C. 3D food printing: Principles of obtaining digitally-designed nourishment. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.M.; Gruppi, A.; Vieira, M.V.; Matos, G.S.; Spigno, G.; Pastrana, L.M.; Teixeira, A.C.; Fuci, P. How additive manufacturing can boost the bioactivity of baked functional foods. J. Food Eng. 2021, 294, 110394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition | Amount (% DW) |

|---|---|

| Total sugar | 45.1 ± 5.3 |

| Total dietary fiber | 26.5 ± 0.8 |

| Insoluble fiber | 18.4 ± 0.4 |

| Soluble fiber | 8.2 ± 0.5 |

| Total phenolic content (mg EGA/100 g AP) | 289.1 ± 24.2 |

| Fat | 3.8 ± 0.2 |

| Protein 2 | 3.8 ± 0.0 |

| Polyphenolic profile | (mg/100 g dry matter) |

| Quercetin-3-O-galactoside | 22.55 ± 0.34 |

| Quercetin-3-O-xyloside | 13.91 ± 0.03 |

| Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside | 19.21 ± 0.00 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 20.55 ± 0.12 |

| p-coumaroylquinic acid | 0.16 ± 0.03 |

| Catechin | 1.44 ± 0.02 |

| Procyanidin B2 | 2.61 ± 0.00 |

| Phloretin-2-O-xylosyl-glucoside | 1.48 ± 0.14 |

| Phlorizin | 15.52 ± 0.00 |

| Compound | Amount (% DW) | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat Bran | Rice Bran | Oat Bran | Corn Bran | ||

| Water | 12.1 | 8.72- | 29.4–31.2 | 4 | [70,71,72,73] |

| Protein | 13.2–18.4 | 10–16 | 5.9–6.7 | 9.5–10.1 | [71,74,75] |

| Fat | 3.5–3.9 | 15–22 | 6.47 | 1.92–6.41 | [74,76,77,78] |

| Total carbohydrates | 56.8 | 34.1–52.3 | 66.22 | 78.05–79.7 | [74,76,77,78] |

| Starch | 13.8–24.9 | 18.19–32.45 | 2.5–16.3 | 27.7–28.2 | [70,72] |

| Cellulose | 10.5–14.8 | 15.8 | 3.4 | 23–23.1 | [72,79] |

| Hemicellulose | 35.5–39.2 | 31.3 | 35% | 26.1–27 | [72,79,80] |

| Lignin | 8.3–12.5 | 11.6 | 11.22 | 2.2–6.5 | [72,79] |

| Total arabinoxylans | 10.9–26.0 | 4.8–5.1 | 3 | 17.5–17.7 | [70,79,81] |

| Total β-glucan | 2.1–2.5 | 0.04–0.21 | 5.4–8.5 | - | [79,81] |

| Phenolic acids | 1.1 | 1.57 | 0.7–1 | 2.2-2.7 | [71,74,82] |

| Ferulic acid | 0.02–1.5 | 0.004 | 1.76 | 1.5–1.9 | [70,82,83] |

| Phytic acid | 4.2–5.4 | 50.68 * | - | - | [74] |

| Ash | 3.4–8.1 | 10.65 | 10.3–10.9 | 4 | [71,73] |

| Geographical Origin | Tomato By-Products | Extraction Method | Total Phenolic Content | Antioxidant Activity | Antimicrobial Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | Peels | Solvent extraction | 33.5 mg TAE/100 g | 21.0% inhibition/g | - | [94] |

| Seeds | 20.11 mg TAE/100 g meal | 34.0% inhibition/g | - | |||

| Romania | Seeds and peels of 10 varieties of tomato | 111.9 to 407.7 mg/100 g DW | Mean value of 489.9 ± 41.5 µmol TE/100 g | Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria | [99] | |

| Peels of 10 varieties of tomato | 35 to 157 mg/ 100 g DW | Mean value of 201 ± 44 µmol TE/100 g | [95] | |||

| Portugal | Whole tomato | 408.89 ± 12.11 and 277.24 ± 11.29 mg GAE/100 g DM (fresh and after 6 months of frozen storage); 310.33 ± 10.38 and 283.64 ± 11.84 mg GAE/100 g DW (before and after 6 months of powder storage) | ABTS (694.07 ± 45.00 and 558.73 ± 29.06 mg TE/100 g in fresh and after 6 months of frozen storage; 350.15 ± 14.37 and 407.56 ± 25.93 mg TE/100 g before and after 6 months of powder storage) | Enterobacteriaceae, Bacillus cereus spp., yeasts, and molds | [104] | |

| ORAC (3165.18 ± 77.48 mg TE/100 g, 3285.77 ± 271.25 mg TE/100 g 1771.66 ± 31.25 mg TE/100 g in fresh and after 1 to 6 months of frozen storage; 1581.76 ± 124.90 TE/100 g, 1610.74 ± 46.51 mg TE/100 g and 1229.74 ± 38.52 mg TE/100 g before and after 2 to 6 months of powder storage) | ||||||

| DPPH (418.79 ± 30.92, 648.06 ± 55.38, 388.53 ± 27.18 mg TE/100 g in fresh and after 3 to 6 months of frozen storage; 117.78 ± 4.99 to 130.44 ± 3.51 mg TE/ 100 g before and after 6 months of powder storage) | ||||||

| Spain | Peels fiber | Enzyme hydrolysis | 291.14 ± 11.1 to 353.15 ± 19.6 mg GAE/kg | 3.90 µmol TEAC/g | - | [105] |

| Maceration | 749.84 ± 15.55 mg GAE/kg | |||||

| Ultrasonic assistance (5 to 15 min) | 985.78 ± 112.93 to 1056.18 ±67.9 mg GAE/kg |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szabo, K.; Mitrea, L.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Teleky, B.-E.; Martău, G.A.; Plamada, D.; Pascuta, M.S.; Nemeş, S.-A.; Varvara, R.-A.; Vodnar, D.C. Natural Polyphenol Recovery from Apple-, Cereal-, and Tomato-Processing By-Products and Related Health-Promoting Properties. Molecules 2022, 27, 7977. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27227977

Szabo K, Mitrea L, Călinoiu LF, Teleky B-E, Martău GA, Plamada D, Pascuta MS, Nemeş S-A, Varvara R-A, Vodnar DC. Natural Polyphenol Recovery from Apple-, Cereal-, and Tomato-Processing By-Products and Related Health-Promoting Properties. Molecules. 2022; 27(22):7977. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27227977

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzabo, Katalin, Laura Mitrea, Lavinia Florina Călinoiu, Bernadette-Emőke Teleky, Gheorghe Adrian Martău, Diana Plamada, Mihaela Stefana Pascuta, Silvia-Amalia Nemeş, Rodica-Anita Varvara, and Dan Cristian Vodnar. 2022. "Natural Polyphenol Recovery from Apple-, Cereal-, and Tomato-Processing By-Products and Related Health-Promoting Properties" Molecules 27, no. 22: 7977. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27227977

APA StyleSzabo, K., Mitrea, L., Călinoiu, L. F., Teleky, B. -E., Martău, G. A., Plamada, D., Pascuta, M. S., Nemeş, S. -A., Varvara, R. -A., & Vodnar, D. C. (2022). Natural Polyphenol Recovery from Apple-, Cereal-, and Tomato-Processing By-Products and Related Health-Promoting Properties. Molecules, 27(22), 7977. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27227977