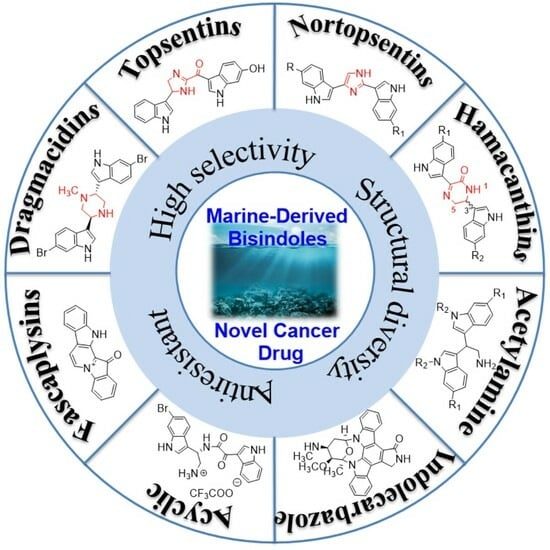

Marine-Derived Bisindoles for Potent Selective Cancer Drug Discovery and Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Topsentin Family Bisindole Alkaloids and Their Derivatives

3. Nortopsentin Family Bisindole Alkaloids and Their Derivatives

4. Hamacanthin Family Bisindole Alkaloids and Their Derivatives

5. Dragmacidin Family Bisindole Alkaloids and Their Derivatives

6. Fascaplysin Family Bisindole Alkaloids and Their Derivatives

7. Bisindole Acetylamine Alkaloids and Their Derivatives

8. Acyclic Structure-Linked Bisindole Alkaloids and Their Derivatives

9. Indolecarbazole Bisindole Alkaloids and Their Derivatives

10. Other Bisindole Alkaloids

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sudhakar, A. History of Cancer, Ancient and Modern Treatment Methods. J. Cancer Sci. Ther. 2009, 1, i–iv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Dong, W.; Guo, Q.; Li, X.; Huang, L. The Importance of Indole and Azaindole Scaffold in the Development of Antitumor Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 203, 112506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayona, L.M.; de Voogd, N.J.; Choi, Y.H. Metabolomics on the Study of Marine Organisms. Metabolomics 2022, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigwart, J.D.; Blasiak, R.; Jaspars, M.; Jouffray, J.-B.; Tasdemir, D. Unlocking the Potential of Marine Biodiscovery. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2021, 38, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Bi, K.; Liu, J.; Cao, S.; Liu, M.; Pešić, M.; Lin, X. Protein Kinases as Targets for Developing Anticancer Agents from Marine Organisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Gen. Subj. 2021, 1865, 129759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, N.; Parveen, S.; Tang, T.; Wei, J.; Huang, Z. Marine Natural Products in Clinical Use. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.P.; Singh, O.M. Recent Progress in Biological Activities of Indole and Indole Alkaloids. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Xu, Z. Indole Alkaloids with Potential Anticancer Activity. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 1938–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; Yang, F.; Dong, S. Marine Indole Alkaloids—Isolation, Structure and Bioactivities. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzen, S. Recent Studies and Biological Aspects of Substantial Indole Derivatives with Anti-Cancer Activity. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Peng, R.; Min, Q.; Hui, S.; Chen, X.; Yang, G.; Qin, S. Bisindole Natural Products: A Vital Source for the Development of New Anticancer Drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 243, 114748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujii, S.; Rinehart, K.L.; Gunasekera, S.P.; Kashman, Y.; Cross, S.S.; Lui, M.S.; Pomponi, S.A.; Diaz, M.C. Topsentin, Bromotopsentin, and Dihydrodeoxybromotopsentin: Antiviral and Antitumor Bis(Indolyl)Imidazoles from Caribbean Deep-Sea Sponges of the Family Halichondriidae. Structural and Synthetic Studies. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 5446–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burres, N.S.; Barber, D.A.; Gunasekera, S.P.; Shen, L.L.; Clement, J.J. Antitumor Activity and Biochemical Effects of Topsentin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1991, 42, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartik, K.; Braekman, J.-C.; Daloze, D.; Stoller, C.; Huysecom, J.; Vandevyver, G.; Ottinger, R. Topsentins, New Toxic Bis-Indole Alkaloids from the Marine Sponge Topsentia Genitrix. Can. J. Chem. 1987, 65, 2118–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casapullo, A.; Bifulco, G.; Bruno, I.; Riccio, R. New Bisindole Alkaloids of the Topsentin and Hamacanthin Classes from the Mediterranean Marine Sponge Rhaphisia Lacazei. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitora, Y.; Takada, K.; Ise, Y.; Okada, S.; Matsunaga, S. Dragmacidins G and H, Bisindole Alkaloids Tethered by a Guanidino Ethylthiopyrazine Moiety, from a Lipastrotethya Sp. Marine Sponge. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 2973–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.-B.; Mar, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.-Y.; Lee, T.-H.; Kim, J.-G.; Shin, D.; Sim, C.J.; Shin, J. Antimicrobial Activity and Cytotoxicity of Bis(Indole) Alkaloids from the Sponge Spongosorites sp. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 29, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakemi, S.; Sun, H.H. Nortopsentins A, B, and C. Cytotoxic and Antifungal Imidazolediylbis[Indoles] from the Sponge Spongosorites Ruetzleri. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 4304–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Seo, Y.; Cho, K.W.; Rho, J.-R.; Sim, C.J. New Bis(Indole) Alkaloids of the Topsentin Class from the Sponge Spongosorites genitrix. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 647–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, B.; Sun, Q.; Yao, X.; Hong, J.; Lee, C.-O.; Sim, C.J.; Im, K.S.; Jung, J.H. Cytotoxic Bisindole Alkaloids from a Marine Sponge Spongosorites sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascioferro, S.; Li Petri, G.; Parrino, B.; El Hassouni, B.; Carbone, D.; Arizza, V.; Perricone, U.; Padova, A.; Funel, N.; Peters, G.J.; et al. 3-(6-Phenylimidazo [2,1-b][1,3,4]Thiadiazol-2-Yl)-1H-Indole Derivatives as New Anticancer Agents in the Treatment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Molecules 2020, 25, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Petri, G.; Cascioferro, S.; El Hassouni, B.; Carbone, D.; Parrino, B.; Cirrincione, G.; Peters, G.J.; Diana, P.; Giovannetti, E. Biological Evaluation of the Antiproliferative and Anti-Migratory Activity of a Series of 3-(6-Phenylimidazo [2,1- b ][1,3,4]Thiadiazol-2-Yl)-1 H -Indole Derivatives Against Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 3615–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mérour, J.-Y.; Buron, F.; Plé, K.; Bonnet, P.; Routier, S. The Azaindole Framework in the Design of Kinase Inhibitors. Molecules 2014, 19, 19935–19979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrino, B.; Carbone, A.; Spanò, V.; Montalbano, A.; Giallombardo, D.; Barraja, P.; Attanzio, A.; Tesoriere, L.; Sissi, C.; Palumbo, M.; et al. Aza-Isoindolo and Isoindolo-Azaquinoxaline Derivatives with Antiproliferative Activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 94, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrino, B.; Carbone, A.; Ciancimino, C.; Spanò, V.; Montalbano, A.; Barraja, P.; Cirrincione, G.; Diana, P.; Sissi, C.; Palumbo, M.; et al. Water-Soluble Isoindolo [2,1-a]Quinoxalin-6-Imines: In Vitro Antiproliferative Activity and Molecular Mechanism(s) of Action. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 94, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, D.; Parrino, B.; Cascioferro, S.; Pecoraro, C.; Giovannetti, E.; Di Sarno, V.; Musella, S.; Auriemma, G.; Cirrincione, G.; Diana, P. 1,2,4-Oxadiazole Topsentin Analogs with Antiproliferative Activity against Pancreatic Cancer Cells, Targeting GSK3β Kinase. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecoraro, C.; Parrino, B.; Cascioferro, S.; Puerta, A.; Avan, A.; Peters, G.J.; Diana, P.; Giovannetti, E.; Carbone, D. A New Oxadiazole-Based Topsentin Derivative Modulates Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 1 Expression and Exerts Cytotoxic Effects on Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Molecules 2021, 27, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, M.M.; Abdel-hameid, M.K.; El-Nassan, H.B.; El-Khouly, E.A. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Biological Applications of Nortopsentin Analogs. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2020, 56, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, P.; Carbone, A.; Barraja, P.; Montalbano, A.; Martorana, A.; Dattolo, G.; Gia, O.; Via, L.D.; Cirrincione, G. Synthesis and Antitumor Properties of 2,5-Bis(3′-Indolyl)Thiophenes: Analogues of Marine Alkaloid Nortopsentin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 2342–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diana, P.; Carbone, A.; Barraja, P.; Martorana, A.; Gia, O.; DallaVia, L.; Cirrincione, G. 3,5-Bis(3′-Indolyl)Pyrazoles, Analogues of Marine Alkaloid Nortopsentin: Synthesis and Antitumor Properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 6134–6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana, P.; Carbone, A.; Barraja, P.; Kelter, G.; Fiebig, H.-H.; Cirrincione, G. Synthesis and Antitumor Activity of 2,5-Bis(3′-Indolyl)-Furans and 3,5-Bis(3′-Indolyl)-Isoxazoles, Nortopsentin Analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 4524–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Parrino, B.; Barraja, P.; Spanò, V.; Cirrincione, G.; Diana, P.; Maier, A.; Kelter, G.; Fiebig, H.-H. Synthesis and Antiproliferative Activity of 2,5-Bis(3′-Indolyl)Pyrroles, Analogues of the Marine Alkaloid Nortopsentin. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreenivasulu, R.; Tej, M.B.; Jadav, S.S.; Sujitha, P.; Kumar, C.G.; Raju, R.R. Synthesis, Anticancer Evaluation and Molecular Docking Studies of 2,5-Bis(Indolyl)-1,3,4-Oxadiazoles, Nortopsentin Analogues. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1208, 127875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Kumar, N.M.; Chang, K.-H.; Gupta, R.; Shah, K. Synthesis and In-Vitro Anticancer Activity of 3,5-Bis(Indolyl)-1,2,4-Thiadiazoles. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 5897–5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrino, B.; Attanzio, A.; Spanò, V.; Cascioferro, S.; Montalbano, A.; Barraja, P.; Tesoriere, L.; Diana, P.; Cirrincione, G.; Carbone, A. Synthesis, Antitumor Activity and CDK1 Inhibiton of New Thiazole Nortopsentin Analogues. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 138, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrino, B.; Carbone, A.; Di Vita, G.; Ciancimino, C.; Attanzio, A.; Spanò, V.; Montalbano, A.; Barraja, P.; Tesoriere, L.; Livrea, M.; et al. 3-[4-(1H-Indol-3-Yl)-1,3-Thiazol-2-Yl]-1H-Pyrrolo [2,3-b]Pyridines, Nortopsentin Analogues with Antiproliferative Activity. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 1901–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Pennati, M.; Parrino, B.; Lopergolo, A.; Barraja, P.; Montalbano, A.; Spanò, V.; Sbarra, S.; Doldi, V.; De Cesare, M.; et al. Novel 1 H -Pyrrolo [2,3- b ]Pyridine Derivative Nortopsentin Analogues: Synthesis and Antitumor Activity in Peritoneal Mesothelioma Experimental Models. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 7060–7072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Pennati, M.; Barraja, P.; Montalbano, A.; Parrino, B.; Spano, V.; Lopergolo, A.; Sbarra, S.; Doldi, V.; Zaffaroni, N.; et al. Synthesis and Antiproliferative Activity of Substituted 3[2-(1H-Indol-3-Yl)- 1,3-Thiazol-4-Yl]-1H-Pyrrolo [3,2-b]Pyridines, Marine Alkaloid Nortopsentin Analogues. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 1654–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascioferro, S.; Attanzio, A.; Di Sarno, V.; Musella, S.; Tesoriere, L.; Cirrincione, G.; Diana, P.; Parrino, B. New 1,2,4-Oxadiazole Nortopsentin Derivatives with Cytotoxic Activity. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanò, V.; Attanzio, A.; Cascioferro, S.; Carbone, A.; Montalbano, A.; Barraja, P.; Tesoriere, L.; Cirrincione, G.; Diana, P.; Parrino, B. Synthesis and Antitumor Activity of New Thiazole Nortopsentin Analogs. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, B.; Sun, Q.; Yao, X.; Hong, J.; Lee, C.-O.; Cho, H.Y.; Jung, J.H. Bisindole Alkaloids of the Topsentin and Hamacanthin Classes from a Marine Sponge Spongosorites Sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Cheong, O.; Bae, S.; Shin, J.; Lee, S. 6″-Debromohamacanthin A, a Bis (Indole) Alkaloid, Inhibits Angiogenesis by Targeting the VEGFR2-Mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathways. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 1087–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Gu, X.-H. Syntheses and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Bis(Indolyl)Thiazole, Bis(Indolyl)Pyrazinone and Bis(Indolyl)Pyrazine: Analogues of Cytotoxic Marine Bis(Indole) Alkaloid. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000, 8, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohmoto, S.; Kashman, Y.; Mcconnell, O.J.; Rinehart, K.L.J.; Wright, A.; Koehn, F. ChemInform Abstract: Dragmacidin, a New Cytotoxic Bis(Indole) Alkaloid from a Deep Water Marine Sponge, Dragmacidon sp. ChemInform 1988, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.A.; Andersen, R.J. ChemInform Abstract: Brominated Bis(Indole) Alkaloids from the Marine Sponge Hexadella sp. ChemInform 1990, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, P.G.; Martínez Leal, J.F.; Daranas, A.H.; Pérez, M.; Cuevas, C. On the Mechanism of Action of Dragmacidins I and J, Two New Representatives of a New Class of Protein Phosphatase 1 and 2A Inhibitors. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 3760–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, A.; Killday, K.; Chakrabarti, D.; Guzmán, E.; Harmody, D.; McCarthy, P.; Pitts, T.; Pomponi, S.; Reed, J.; Roberts, B.; et al. Dragmacidin G, a Bioactive Bis-Indole Alkaloid from a Deep-Water Sponge of the Genus Spongosorites. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B. Synthesis and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Novel Indolylpyrimidines and Indolylpyrazines as Potential Antitumor Agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001, 9, 1149–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, B.; Hochmair, M.; Plangger, A.; Hamilton, G. Anticancer Activity of Fascaplysin against Lung Cancer Cell and Small Cell Lung Cancer Circulating Tumor Cell Lines. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryukhovetskiy, I.; Lyakhova, I.; Mischenko, P.; Milkina, E.; Zaitsev, S.; Khotimchenko, Y.; Bryukhovetskiy, A.; Polevshchikov, A.; Kudryavtsev, I.; Khotimchenko, M.; et al. Alkaloids of Fascaplysin Are Effective Conventional Chemotherapeutic Drugs, Inhibiting the Proliferation of C6 Glioma Cells and Causing Their Death in Vitro. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Guan, X.; Wang, L.-L.; Li, B.; Sang, X.-B.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Fascaplysin Inhibit Ovarian Cancer Cell Proliferation and Metastasis through Inhibiting CDK4. Gene 2017, 635, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahgoub, T.; Eustace, A.J.; Collins, D.M.; Walsh, N.; O’Donovan, N.; Crown, J. Kinase Inhibitor Screening Identifies CDK4 as a Potential Therapeutic Target for Melanoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 47, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, T.-I.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Nam, T.-J.; Kim, Y.-S.; Kim, B.; Yim, W.; Lim, J.-H. Fascaplysin Sensitizes Anti-Cancer Effects of Drugs Targeting AKT and AMPK. Molecules 2017, 23, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Guru, S.K.; Pathania, A.S.; Manda, S.; Kumar, A.; Bharate, S.B.; Vishwakarma, R.A.; Malik, F.; Bhushan, S. Fascaplysin Induces Caspase Mediated Crosstalk Between Apoptosis and Autophagy Through the Inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Cascade in Human Leukemia HL-60 Cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, N.; Mu, X.; Lv, X.; Wang, L.; Li, N.; Gong, Y. Autophagy Represses Fascaplysin-Induced Apoptosis and Angiogenesis Inhibition via ROS and P8 in Vascular Endothelia Cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 114, 108866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, T.-I.; Lee, Y.-M.; Nam, T.-J.; Ko, Y.-S.; Mah, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Reddy, R.; Kim, Y.; Hong, S.; et al. Fascaplysin Exerts Anti-Cancer Effects through the Downregulation of Survivin and HIF-1α and Inhibition of VEGFR2 and TRKA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhidkov, M.E.; Kantemirov, A.V.; Koisevnikov, A.V.; Andin, A.N.; Kuzmich, A.S. Syntheses of the Marine Alkaloids 6-Oxofascaplysin, Fascaplysin and Their Derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018, 59, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyakhova, I.A.; Bryukhovetsky, I.S.; Kudryavtsev, I.V.; Khotimchenko, Y.S.; Zhidkov, M.E.; Kantemirov, A.V. Antitumor Activity of Fascaplysin Derivatives on Glioblastoma Model In Vitro. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2018, 164, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Guru, S.K.; Manda, S.; Kumar, A.; Mintoo, M.J.; Prasad, V.D.; Sharma, P.R.; Mondhe, D.M.; Bharate, S.B.; Bhushan, S. A Marine Sponge Alkaloid Derivative 4-Chloro Fascaplysin Inhibits Tumor Growth and VEGF Mediated Angiogenesis by Disrupting PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Cascade. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017, 275, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantenuto, S.; Lucarini, S.; De Santi, M.; Piersanti, G.; Brandi, G.; Favi, G.; Mantellini, F. One-Pot Synthesis of Biheterocycles Based on Indole and Azole Scaffolds Using Tryptamines and 1,2-Diaza-1,3-Dienes as Building Blocks: One-Pot Synthesis of Biheterocycles Based on Indole and Azole Scaffolds Using Tryptamines and 1,2-Diaza-1,3-Dienes as Building Blocks. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2016, 3193–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, M.; Tassoni, A.; Lucarini, S.; Fanelli, M.; Piersanti, G.; Spadoni, G. Brønsted Acid Catalyzed Bisindolization of α-Amido Acetals: Synthesis and Anticancer Activity of Bis(Indolyl)Ethanamino Derivatives: Brønsted Acid Catalyzed Bisindolization of α-Amido Acetals. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 2014, 3822–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salucci, S.; Burattini, S.; Buontempo, F.; Orsini, E.; Furiassi, L.; Mari, M.; Lucarini, S.; Martelli, A.M.; Falcieri, E. Marine Bisindole Alkaloid: A Potential Apoptotic Inducer in Human Cancer Cells. Eur. J. Histochem. 2018, 62, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burattini, S.; Battistelli, M.; Verboni, M.; Falcieri, E.; Faenza, I.; Lucarini, S.; Salucci, S. Morpho-functional Analyses Reveal That Changes in the Chemical Structure of a Marine Bisindole Alkaloid Alter the Cytotoxic Effect of Its Derivatives. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2022, 85, 2381–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, L.K.; Khan, N.M.D.; Kaur, N.; Rodrigues, D.; Morrow, C.; Boyd, A.; Thomas, O.P. Brominated Bisindole Alkaloids from the Celtic Sea Sponge Spongosorites Calcicola. Molecules 2019, 24, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Cho, E.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Park, S.C.; Chung, B.; Kwon, O.-S.; Sim, C.J.; Oh, D.-C.; Oh, K.-B.; Shin, J. Bioactive Bis(Indole) Alkaloids from a Spongosorites sp. Sponge. Mar. Drugs 2020, 19, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gamal, A.A.; Wang, W.-L.; Duh, C.-Y. Sulfur-Containing Polybromoindoles from the Formosan Red Alga Laurencia b Rongniartii. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 815–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuda, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Fromont, J.; Mikami, Y.; Kobayashi, J. Dendridine A, a Bis-Indole Alkaloid from a Marine Sponge Dictyodendrilla Species. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1277–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, J.A.; Flower, P.B.; Seldes, A.M. Chondriamides A and B, New Indolic Metabolites from the Red Alga Chondria Sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 3097–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberio, M.; Sadowski, M.; Nelson, C.; Davis, R. Identification of Eusynstyelamide B as a Potent Cell Cycle Inhibitor Following the Generation and Screening of an Ascidian-Derived Extract Library Using a Real Time Cell Analyzer. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 5222–5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, M.; Tabudravu, J.N.; Jaspars, M.; Strøm, M.B.; Hansen, E.; Andersen, J.H.; Kristiansen, P.E.; Haug, T. The Antibacterial Ent-Eusynstyelamide B and Eusynstyelamides D, E, and F from the Arctic Bryozoan Tegella Cf. Spitzbergensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasulu, R.; Durgesh, R.; Jadav, S.S.; Sujitha, P.; Ganesh Kumar, C.; Raju, R.R. Synthesis, Anticancer Evaluation and Molecular Docking Studies of Bis(Indolyl) Triazinones, Nortopsentin Analogs. Chem. Pap. 2018, 72, 1369–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayler, K.M.; Kong, K.; Reisenauer, K.; Taube, J.H.; Wood, J.L. Staurosporine Analogs Via C–H Borylation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2441–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsamman, K.; El-Masry, O. Staurosporine Alleviates Cisplatin Chemoresistance in Human Cancer Cell Models by Suppressing the Induction of SQSTM1/P62. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 2157–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malsy, M.; Bitzinger, D.; Graf, B.; Bundscherer, A. Staurosporine Induces Apoptosis in Pancreatic Carcinoma Cells PaTu 8988t and Panc-1 via the Intrinsic Signaling Pathway. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2019, 24, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ge, J. Staurosporine Suppresses Survival of HepG2 Cancer Cells through Omi/HtrA2-Mediated Inhibition of PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Tumor Biol. 2017, 39, 101042831769431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, K.; Xue, J.; Small, A.; Xiao, G.; Nguyen, L.X.T.; Zhang, Z.; Prince, E.; Weng, H.; Huang, H.; et al. Phosphorylation Stabilized TET1 Acts as an Oncoprotein and Therapeutic Target in B Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabq8513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Hu, Z.-J.; Zhang, H.-J.; Li, J.-Q.; Ding, W.-J.; Ma, Z.-J. Bioactive Staurosporine Derivatives from the Streptomyces sp. NB-A13. Bioorganic Chem. 2019, 82, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, N.; Kuwabara, T.; Tanii, H.; Fuse, E.; Akiyama, T.; Akinaga, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kobayashi, S. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of a Novel Protein Kinase Inhibitor, UCN-01. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1999, 44, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Bower, M.J.; McDevitt, P.J.; Zhao, H.; Davis, S.T.; Johanson, K.O.; Green, S.M.; Concha, N.O.; Zhou, B. Structural Basis for Chk1 Inhibition by UCN-01 and Its Analogs. Acta Crystallogr. A 2002, 58, c224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Fujita, N.; Tsuruo, T. Interference with PDK1-Akt Survival Signaling Pathway by UCN-01 (7-Hydroxystaurosporine). Oncogene 2002, 21, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, W.; Chen, T.; Sheu, S.; Lin, T.; Kang, F.; Yu, C.; Kuan, T.; Huang, B.; Wang, C. 7-hydroxy-staurosporine, UCN-01, Induces DNA Damage Response, and Autophagy in Human Osteosarcoma U2-OS Cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 4729–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candido, M.F.; Medeiros, M.; Veronez, L.C.; Bastos, D.; Oliveira, K.L.; Pezuk, J.A.; Valera, E.T.; Brassesco, M.S. Drugging Hijacked Kinase Pathways in Pediatric Oncology: Opportunities and Current Scenario. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, A.; Romeo, M.A.; Benedetti, R.; Gilardini Montani, M.S.; Cirone, M. The Impairment of DDR Reduces XBP1s, Further Increasing DNA Damage, and Triggers Autophagy via PERK/eIF2alpha in MM and IRE1alpha/JNK1/2 in PEL Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 613, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, M.; Allebach, J.; Tse, K.-F.; Zheng, R.; Baldwin, B.R.; Smith, B.D.; Jones-Bolin, S.; Ruggeri, B.; Dionne, C.; Small, D. A FLT3-Targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Is Cytotoxic to Leukemia Cells in Vitro and in Vivo. Blood 2002, 99, 3885–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, S.A.; Kung, A.L.; Mabon, M.E.; Silverman, L.B.; Stam, R.W.; Den Boer, M.L.; Pieters, R.; Kersey, J.H.; Sallan, S.E.; Fletcher, J.A.; et al. Inhibition of FLT3 in MLL. Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, H.; Pierro, L.; Reina, M.; Gallagher, W.M.; Prencipe, M. Emerging Role for the Serum Response Factor (SRF) as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2022, 26, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.T.; Levis, M. Lestaurtinib: A Multi-Targeted FLT3 Inhibitor. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2009, 2, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfield, L.C.; Pollyea, D.A. Midostaurin: A New Oral Agent Targeting FMS -Like Tyrosine Kinase 3-Mutant Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2017, 37, 1586–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S. Midostaurin: First Global Approval. Drugs 2017, 77, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, M. Midostaurin Approved for FLT3-Mutated AML. Blood 2017, 129, 3403–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhuang, Y.; Sun, K.; Zhu, W. Synthesis and Cytotoxicity of Halogenated Derivatives of PKC-412. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 34, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Mei, X.; Wang, C.; Zhu, W. Biomimetic Semi-Synthesis of Fradcarbazole A and Its Analogues. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 7990–7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, Y.; Zuo, M.; Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Zhu, W. Semisynthetic Derivatives of Fradcarbazole A and Their Cytotoxicity against Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cell Lines. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 2279–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, D.; Xu, Y.; He, W.; Wang, D.; Zhu, W.; Wang, L. Synthesis and Antitumor Activity of Staurosporine Derivatives. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2022, 17, 1934578X2211030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, P.; Bernal, M.; Téllez-Quijorna, C.; Marrero, A.D.; Vidal, I.; Castilla, L.; Caro, C.; Domínguez, A.; García-Martín, M.L.; Quesada, A.R.; et al. The Synthetic Molecule Stauprimide Impairs Cell Growth and Migration in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 158, 114070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourhill, T.; Narendran, A.; Johnston, R.N. Enzastaurin: A Lesson in Drug Development. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 112, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T.; Li, P.; Wang, C.; Tang, X.; Cheng, M.; Zong, Y.; Luo, L.; Ou, H.; Liu, K.; Li, G. Racemic Bisindole Alkaloids: Structure, Bioactivity, and Computational Study. Chin. J. Chem. 2021, 39, 2588–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Tsuda, M.; Watanabe, K.; Kobayashi, J. Rhopaladins A ∼ D, New Indole Alkaloids from Marine Tunicate Rhopalaea sp. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 8687–8690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, T.; Tsuda, M.; Fromont, J.; Kobayashi, J. Hyrtinadine A, a Bis-Indole Alkaloid from a Marine Sponge. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 423–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasch, B.O.A.; Merkul, E.; Müller, T.J.J. One-Pot Synthesis of Diazine-Bridged Bisindoles and Concise Synthesis of the Marine Alkaloid Hyrtinadine A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 4532–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, L.; Tian, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, C.; Zhang, S.; et al. Spiroindimicins A–D: New Bisindole Alkaloids from a Deep-Sea-Derived Actinomycete. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3364–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Ma, L.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, X.; Yuan, C.; et al. Indimicins A–E, Bisindole Alkaloids from the Deep-Sea-Derived Streptomyces sp. SCSIO 03032. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 1887–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.-Z.; Huang, Z.; Shi, X.-F.; Chen, Y.-C.; Zhang, W.-M.; Tian, X.-P.; Li, J.; Zhang, S. Cytotoxic Indole Diketopiperazines from the Deep Sea-Derived Fungus Acrostalagmus Luteoalbus SCSIO F457. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 7265–7267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishwakarma, K.; Dey, R.; Bhatt, H. Telomerase: A Prominent Oncological Target for Development of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 249, 115121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warabi, K.; Matsunaga, S.; Van Soest, R.W.M.; Fusetani, N. Dictyodendrins A−E, the First Telomerase-Inhibitory Marine Natural Products from the Sponge Dictyodendrilla v Erongiformis 1. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 2765–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Anticancer Activity | CAS Number | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| topsentin B1 (1) | IC50 (P388) = 4.1 ± 1.4 µM; IC50 (HT-29) = 20.5 ± 2.1 µM; IC50 (A549) = 41.1 ± 8.5 µM; IC50 (HL-60) = 15.7 ± 4.3 µM; IC50 (HCT-8;T47D) = 20 µg/mL; IC50 (NSCLC-N6) = 12 µg/mL; IC50 (HeLa) = 4.4 µM. | 112515-44-2 | [12,13,14,15,16] |

| topsentin B2 (2)/bromotopsentin | IC50 (NSCLC-N6) = 6.3 µg/mL; IC50 (HeLa) = 1.7 µM; IC50 (AGS) = 1.4 µg/mL; IC50 (L1210) = 6.9 µg/mL; IC50 (P388) = 7.0 µg/mL. | 112515-44-3 | [12,14,15,16,17,18] |

| 4,5-dihydro-6″-deoxybromotopsentin (3) | IC50 (AGS) = 6.3 µg/mL; IC50 (L1210) = 5.1 µg/mL; IC50(BC) = 17.5 µg/mL; IC50 (P388) = 4.0 µg/mL. | 116747-40-1 | [12,17] |

| deoxytopsentin (4) | IC50 (AGS) = 1.3 µg/mL; IC50 (L1210) = 7.4 µg/mL; IC50 (BC) = 10.7 µg/mL; IC50 (HepG2) = 3.3 µg/mL; IC50 (P388) = 12.0 µg/mL. | 112515-42-1 | [12,17] |

| bromodeoxytopsentin (5) | IC50 (AGS) = 3.3 µg/mL; IC50 (L1210) = 1.1 µg/mL; IC50 (K-562) = 0.6 µg/mL. | 180633-55-0 | [17,19] |

| isobromodeoxytopsentin (6) | IC50 (K-562) = 2.1 µg/mL; ED50 (A549) = 12.3 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 8.7 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 4.54 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 5.51 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 6.38 µg/mL. | 223596-72-3 | [19,20] |

| isotopsentin (7) | IC50 (P388) = 4.0 µg/mL. | 116725-88-3 | [12] |

| hydroxytopsentin (8) | IC50 (P388) = 0.3 µg/mL. | 116725-89-4 | |

| neotopsentin (9) | IC50 (P388) = 2.5 µg/mL. | 116725-90-7 | |

| neoisotopsentin (10) | IC50 (P388) = 1.8 µg/mL. | 116725-91-8 | |

| 11 | EC50 (Panc-1) = 0.8 µM; EC50 (Capan-1) = 1.2 µM; EC50 (SUIT-2) = 0.4 µM. | 2691060-39-4 | [26] |

| 12 | EC50 (Panc-1) = 1.6 µM; EC50 (Capan-1) = 1.3 µM; EC50 (SUIT-2) = 3.2 µM. | 2691060-40-7 | |

| 13 | EC50 (Panc-1) = 2.8 µM; EC50 (Capan-1) = 2.8 µM; EC50 (SUIT-2) = 7.1 µM. | 2691060-45-2 | |

| 14 | EC50 (Panc-1) = 6.8 µM; EC50 (Capan-1) = 2.6 µM; EC50 (SUIT-2) = 5.9 µM. | 2691060-46-3 | |

| 15 | EC50 (Panc-1) = 1.5 µM; EC50 (Capan-1) = 1.4 µM; EC50 (SUIT-2) = 1.9 µM. | 2691060-48-5 | |

| 16 | IC50 (Hs766T) = 5.7 ± 0.60 µM; IC50 (HPAF-II) = 6.9 ± 0.25 µM; IC50 (PDAC3) = 9.8 ± 0.70 µM; IC50 (PDAC3) = 10.7 ± 0.16 µM. | 2986653-16-9 | [27] |

| nortopsentins A (17) | IC50 (P388) = 7.6 µg/mL. | 134029-43-9 | [18] |

| nortopsentins B (18) | IC50 (P388) = 7.8 µg/mL. | 134029-44-0 | |

| nortopsentins C (19) | IC50 (P388) = 1.7 µg/mL. | 134029-45-1 | |

| 20 | GI50 (CCRF-CEM) = 0.34 µM; GI50 (HL-60) = 2.27 µM; GI50 (K-562) = 3.54 µM; GI50 (RPMI-8226) = 2.83 µM; GI50 (MOLT-4) = 1.91 µM; GI50 (NCI-H522) = 1.31 µM; GI50 (HT29) = 2.79 µM; GI50 (LOX IMVI) = 2.55 µM. | 937803-70-8 | [29] |

| 21 | GI50 (MOLT-4) = 4.75 µM; GI50 (SR) = 3.46 µM; GI50 (HOP-92) = 2.06 µM; GI50 (NCI-H460) = 4.48 µM; GI50 (HCC-2998) = 4.74 µM; GI50 (LOX IMVI) = 1.70 µM; GI50 (MCF-7) = 3.95 µM. | 959682-88-3 | [30] |

| 22 | GI50 (MOLT-4) = 1.55 µM; GI50 (SR) = 2.36 µM; GI50 (HOP-92) = 1.86 µM; GI50 (NCI-H460) = 2.35 µM; GI50 (HCC-2998) = 1.71 µM; GI50 (SF-539) = 1.81 µM; GI50 (LOX IMVI) = 1.70 µM; GI50 (SK-MEL-5) = 1.79 µM; GI50 (UACC-62) = 1.63 µM; GI50 (IGROV1) = 2.55 µM; GI50 (CAKI-1) = 1.70 µM; GI50 (MCF-7) = 2.64 µM; GI50 (BT-549) = 2.03 µM. | 959682-91-8 | |

| 23 | IC50 (A549) = 5.1 µg/mL; IC50 (LXFA 629L) = 4.2 µg/mL; IC50 (UXF 1138L) = 4.8 µg/mL | 1237096-77-3 | [31] |

| 24 | GI50 (HL-60) = 1.98 µM; GI50 (K-562) = 2.86 µM; GI50 (RPMI-8226) = 2.25 µM; GI50 (SR) = 1.63 µM; GI50 (SK-MEL-2) = 2.13 µM; GI50 (OVCAR-4) = 2.06 µM; GI50 (OVCAR-5) = 2.79 µM; GI50 (NCI/ADR-RES) = 2.37 µM; GI50 (T-47D) = 2.72 µM; GI50 (SF-539) = 2.47 µM; GI50 (KM12) = 2.73 µM. | 1237096-74-0 | |

| 25 | IC50 (BXF 1218L) = 0.72 µM; IC50 (BXF 1352L) = 0.68 µM; IC50 (LXFL 1121L) = 0.67 µM; IC50 (MEXF 1341L) = 0.52 µM; IC50 (MEXF 276L) = 0.22 µM; IC50 (PAXF PANC1) = 0.74 µM; IC50 (SXF SAOS2) = 0.72 µM; IC50 (UXF 1138L) = 0.72 µM. | 2987346-14-3 | [32] |

| 26 | IC50 (BXF 1218L) = 0.32 µM; IC50 (MEXF 1341L) = 0.19 µM; IC50 (MEXF 276L) = 0.11 µM; IC50 (PRXF PC3M) = 0.32 µM; IC50 (SXF SAOS2) = 0.33 µM. | 2986741-15-3 | |

| 27 | IC50 (MCF-7) = 1.8 ± 0.9 µM; IC50 (Hela) = 9.23 ± 0.58 µM. | 2412145-35-6 | [33] |

| 28 | IC50 (Hela) = 9.4 ± 0.37 µM. | 2412145-36-7 | |

| 29 | IC50 (MCF-7) = 2.6 ± 0.89 µM; IC50 (Hela) = 6.34 ± 0.56 µM; IC50 (A549) = 3.3 ± 0.85 µM. | 2412145-38-9 | |

| 30 | IC50 (LNCAP) = 14.6 µM. | 1338059-36-1 | [34] |

| 31 | GI50 (MDA-MB-468) = 0.03 µM; GI50 (T-47D) = 0.04 µM; GI50 (MCF-7) = 0.05 µM. | 2113670-47-4 | [35] |

| 32 | GI50 (KM12) = 1.77 µM; GI50 (MDA-MB-435) = 0.90 µM; GI50 (T-47D) = 0.65 µM. | 2113670-59-8 | |

| 33 | GI50 (KM12) = 0.76 µM; GI50 (MDA-MB-435) = 0.86 µM; GI50 (T-47D) = 0.42 µM. | 2113670-62-3 | |

| 34 | GI50 (MCF-7) = 1.79 µM; GI50 (T-47D) = 1.97 µM; GI50 (EKVX) = 2.05 µM. | 2113670-63-4 | |

| 35 | GI50 (MDA-MB-435) = 0.03 µM; GI50 (SR) = 0.06 µM; GI50 (NCI-H522) = 0.04 µM. | 1873270-61-1 | [36] |

| 36 | GI50 (MDA-MB-435) = 0.04 µM; GI50 (SR) = 0.14 µM; GI50 (NCI-H522) = 0.05 µM. | 1900737-01-0 | |

| 37 | IC50 (STO) = 0.49 ± 0.07 µM; IC50 (MesoII) = 25.12 ± 3.06 µM. | 1450997-15-5 | [37] |

| 38 | IC50 (STO) = 0.33 ± 0.07 µM; IC50 (MesoII) = 4.11 ± 0.22 µM. | 1450997-40-6 | |

| 39 | IC50 (STO) = 0.43 ± 0.11 µM; IC50 (MesoII) = 4.85 ± 0.64 µM. | 1450997-21-3 | |

| 40 | IC50 (MDA-MB-231) = 9.5 ± 3.3 µM; IC50 (MIAPACA-2) = 11.0 ± 2.1 µM; IC50 (PC3) = 9.3 ± 2.0 µM; IC50 (STO) = 8.1 ± 1.3 µM. | 1639456-87-3 | [38] |

| 41 | IC50 (MDA-MB-231) = 17.5 ± 1.8 µM; IC50 (MIAPACA-2) = 14.5 ± 1.3 µM; IC50 (PC3) = 15.5 ± 1.1 µM; IC50 (STO) = 13.4 ± 1.9 µM. | 1639457-02-5 | [38] |

| 42 | IC50 (MDA-MB-231) = 19.8 ± 2.4 µM; IC50 (MIAPACA-2) = 16.4 ± 1.5 µM; IC50 (PC3) = 17.2 ± 2.5 µM; IC50 (STO) = 16.0 ± 2.4 µM. | 1639457-04-7 | |

| 43 | IC50 (MDA-MB-231) = 15.6 ± 3.2 µM; IC50 (MIAPACA-2) = 14.5 ± 2.9 µM; IC50 (PC3) = 19.4 ± 3.2 µM; IC50 (STO) = 12.5 ± 2.6 µM. | 1639457-05-8 | |

| 44 | IC50 (MDA-MB-231) = 25.0 ± 3.7 µM; IC50 (MIAPACA-2) = 19.4 ± 1.9 µM; IC50 (PC3) = 5.4 ± 1.4 µM; IC50 (STO) = 7.0 ± 2.1 µM. | 1639457-07-0 | |

| 45 | IC50 (MDA-MB-231) = 7.2 ± 0.4 µM; IC50 (MIAPACA-2) = 9.1 ± 3.2 µM; IC50 (PC3) =8.6 ± 4.0 µM; IC50 (STO) = 4.1 ± 1.0µM. | 1639457-08-1 | |

| 46 | IC50 (MDA-MB-231) = 14.6 ± 1.7 µM; IC50 (MIAPACA-2) = 19.7 ± 2.5 µM; IC50 (PC3) = 19.6 ± 2.4 µM; IC50 (STO) = 13.0 ± 1.8 µM. | 1639457-11-6 | |

| 47 | IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.65 ± 0.05 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 1.93 ± 0.06 µM; IC50 (Hela) = 10.56 ± 0.98 µM. | 2354325-51-0 | [39] |

| 48 | IC50 (MCF-7) = 2.41 ± 0.23 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 3.55 ± 0.1 µM; IC50 (Hela) = 13.96 ± 1.41 µM. | 2354325-54-3 | |

| 49 | IC50 (MCF-7) = 2.13 ± 0.12 µM. | 2173313-53-4 | [40] |

| 50 | IC50 (MCF-7) = 3.26 ± 0.19 µM. | 2173313-72-7 | |

| 51 | IC50 (MCF-7) = 5.14 ± 0.34 µM. | 2173313-75-0 | |

| (3S,6R)-6′-debromo-3,4-dihydrohamacanthin A (52) | ED50 (A549) = 7.50 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 12.10 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 13.10 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 19.10 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 6.30 µg/mL. | 264624-44-4 | [41] |

| (3S,6R)-6′′-debromo-3,4-dihydrohamacanthin A (53) | ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 4.92 µg/mL. | 264624-45-5 | |

| trans-3,4-dihydrohamacnathin A (54) | ED50 (A549) = 8.28 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 8.03 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 9.14 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 6.88 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 5.35 µg/mL. | 264624-43-3 | [20] |

| trans-4,5-dihydrohamacanthin A (55) | IC50 (AGS) = 6.3 µg/mL; IC50 (L1210) = 5.3 µg/mL. | 453509-60-9 | [17] |

| hamacanthin A (56) | IC50 (AGS) = 3.9 µg/mL; IC50 (L1210) = 3.0 µg/mL; ED50 (A549) = 4.49 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 5.24 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 5.44 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 5.60 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 4.66 µg/mL. | 160098-92-0 | [17,41] |

| (R)-6′′-debromohamacanthin A (57) | ED50 (A549) = 5.61 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 4.20 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 4.73 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 4.12 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 3.58 µg/mL. | 853998-18-2 | [17,20] |

| (R)-6′-debromohamacanthin A (58) | IC50 (AGS) = 7.5 µg/mL; IC50 (L1210) = 9.0 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 26.91 µg/mL. | 853998-19-3 | [17,20] |

| (S)-6′,6′′-didebromohamacanthin A (59) | ED50 (A549) = 8.30 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 11.50 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 5.00 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 17.10 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 4.10 µg/mL. | 925457-99-4 | [41] |

| (R)-6′-debromohamacanthin B (60) | ED50 (A549) = 3.71 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 8.50 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 7.60 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 8.30 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 4.20 µg/mL. | 869964-40-9 | |

| 6″-debromohamacanthin B (61) | IC50 (AGS) = 7.5 µg/mL; IC50 (L1210) = 7.7 µg/mL; ED50 (A549) = 7.86 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 7.85 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 7.71 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 9.21 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 6.31 µg/mL. | 925458-01-1 | [17,41] |

| (R)-6′,6″-didebromohamacanthin B (62) | ED50 (A549) = 11.70 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 12.60 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 13.70 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 24.10 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 4.79 µg/mL. | 925458-00-0 | [41] |

| hamacanthin B(63) | IC50 (AGS) = 5.1 µg/mL; IC50 (L1210) = 6.7 µg/mL; ED50 (A549) = 2.14 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 2.61 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 1.59 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 2.93 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 1.52 µg/mL. | 160098-93-1 | [17,41] |

| (3S,5R)-6″- debromo-3,4-dihydrohamacanthin B (64) | ED50 (A549) = 4.20 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 6.00 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 7.10 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 6.80 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 6.30 µg/mL. | 264624-40-0 | [41] |

| (3S,5R)-6′-debromo-3,4-dihydrohamacanthin B (65) | ED50 (A549) = 9.67 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 5.67 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 9.74 µg/mL. | 264624-41-1 | |

| cis-3,4-dihydrohamacanthin B (66) | ED50 (A549) = 3.41 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-OV-3) = 3.62 µg/mL; ED50 (SK-MEL-2) = 3.85 µg/mL; ED50 (XF498) = 3.22 µg/mL; ED50 (HCT15) = 2.83 µg/mL. | 264624-39-7 | [20] |

| 67 | GI50 (MCF-7) = 6.60 µM; GI50 (K-562) = 18.8 µM; GI50 (SW620) = 18.9 µM. | 265111-00-0 | [42] |

| dragmacidin (68) | IC50 (P388) = 15 µg/mL; 1-10 µg/mLagainst A-549, HCT-8 and MDAMB cancer cell lines. | 10952015(PubChem CID) | [44] |

| dragmacidon A (69) | ED50 (L1210) = 10 mg/mL; IC50 (A549) = 3.1 µM; IC50 (HT29) = 3.3 µM; IC50 (MDA-MB-231) = 3.8 µM. | 128364-31-8 | [45,46] |

| dragmacidin G (70) | IC50 (PANC-1) = 18 ± 0.4 µM; IC50 (MIA PaCa-2) = 26 ± 1.4 µM; IC50 (BxPC-3) = 14 ± 1.4 µM; IC50 (ASPC-1) = 27 ± 0.8 µM; IC50 (HeLa) = 4.2 µM. | 2044674-17-9 | [16,47] |

| dragmacidin H(71) | IC50 (HeLa) = 4.6 µM. | 2650064-06-3 | [16] |

| 72 | GI50 (MDA-N) = 2.47 µM; GI50 (RXF-393) = 2.73 µM; GI50 (K562) = 2.97 µM. | 265110-98-3 | [43] |

| 73 | GI50 (KM12) = 0.058 µM; GI50 (HCT-15) = 0.248 µM; GI50 (SK-MEL-5) = 0.287 µM. | / | |

| 74 | GI50 (SF-539) = 0.16 µM; GI50 (SR) = 0.22 µM; GI50 (MDA-MB-435) = 0.22 µM. | 289503-31-7 | [48] |

| 75 | GI50 (IGROV1) < 0.01 µM.GI50 (CCRF-CEM) = 1.51 µM; GI50 (HOP-92) = 1.70 µM. | 360062-41-5 | [48] |

| 76 | GI50 (IGROV1) = 1.14 µM.GI50 (CCRF-CEM) = 1.52 µM; GI50 (SN12C) = 1.68 µM. | 360062-43-7 | |

| 77 | GI50 (CCRF-CEM) = 1.13 µM; GI50 (IGROV1) = 1.86 µM; GI50 (HOP-92) = 2.34 µM. | 360062-45-9 | |

| 78 | GI50 (SNB-19) = 1.15 µM; GI50 (NCI-H460) = 2.12 µM; GI50 (MCF-7) = 2.30 µM. | 485830-58-8 | |

| fascaplysin(79) | Fascplysin has a wide range of anti-cancer activities, including NSCLC and SCLC cancer cells, glioma cells, A2780 and OVCAR3 human ovarian cancer cell lines, melanoma cells, etc. | 114719-57-2 | [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] |

| 7-phenyl fascaplysin (80) | IC50 (HeLa) = 290 nM; IC50 (THP-1) = 320 nM; have a significant killing effect against glioma C6 cells. | 2176439-03-3 | [57,58] |

| 3-chloro fascaplysin (81), 3-bromo fascaplysin (82),10-bromo fascaplysin (83) | Have a significant killing effect against glioma C6 cells. No accurate data on activity are provided in the literature. | 1827526-66-8;959930-44-0;959930-45-1 | [58] |

| BrBin(84) | IC50 (MCF-7) = 4.4 ± 1.9 µM; IC50 (Caco-2) = 1.5 ± 0.2 µM; GI50 (U937) values in the 1-1.3 µM range. | 135077-20-2 | [60,61] |

| 85,86,87 | Compounds 87 and 88 reduced U937 cell viability by about 10% compared with BrBin, and compound 89 induced more dead cells. No accurate data on activity are provided in the literature. | 3616-44-2;2144744-62-5;1905457-00-2 | [63] |

| calcicamide A (88) | IC50(HeLa) >200 µM. | / | [64] |

| calcicamide B (89) | IC50 (HeLa) = 146 ± 13 µM. | / | |

| spongocarbamide A (90) | IC50 (Srt A) = 79.4 µM; IC50 (K562) = 92.8 µM. | / | [65] |

| spongocarbamide B (91) | IC50 (Srt A) = 52.4 µM | / | |

| 92 | Have inhibitory effect against HT-29 and P388 cancer cells. No accurate data on activity are provided in the literature. | 854781-00-3 | [66] |

| 93 | Have an inhibitory effect against P388 cells. No accurate data on activity are provided in the literature. | 854781-01-4 | |

| dendridine A (94) | IC50 (L1210) = 32.5 µg/mL. | 862844-50-6 | [67] |

| chondriamide A (95) | IC50 (KB) = 0.5 µg/mL; IC50 (LOVO) = 5 µg/mL. | 142677-09-6 | [68] |

| chondriamide B (96) | IC50 (KB) < 1 µg/mL; IC50 (LOVO) = 10 µg/mL. | 142677-10-9 | |

| eusynstyelamide B (97) | IC50 (MDA-MB-231) = 5.0 µM. | 1166392-99-9 | [69] |

| eusynstyelamide D (98) | IC50 (A-2058) = 57 µM. | 1280219-08-0 | [70] |

| eusynstyelamide E (99) | IC50 (A-2058) = 114.3 µM. | 1280219-14-8 | |

| 100 | Showed significant antiproliferative activity against human cervical cancer cell lines, with IC50 values of 4.6 µM. | 2226102-19-6 | [71] |

| 101 | Showed significant antiproliferative activity against human cervical cancer cell lines, with IC50 values of 1.3 µM. | 2226102-19-6 | |

| staurosporine (102) | It has good anti-tumor potential and has been widely studied as a lead compound. IC50 (PC-3) = 58.94 ± 2.30 nM; IC50 (SW-620) = 25.10 ± 3.20 nM | 62996-74-1 | [72,73,74,75,76,77] |

| 103 | IC50 (PC-3) = 4.03 ± 0.29 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 2.14 ± 0.08 µM. | 2242549-12-6 | [77] |

| 104 | IC50 (PC-3) = 2.05 ± 0.06 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 0.74 ± 0.01 µM. | 2242549-13-7 | |

| 105 | IC50 (PC-3) = 2.45 ± 0.08 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 2.00 ± 0.19 µM. | 2102303-78-4 | |

| 106 | IC50 (PC-3) = 16.60 ± 0.43 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 9.54 ± 0.65 µM. | 2242549-14-8 | |

| 107 | IC50 (PC-3) = 0.55 ± 0.04 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 0.16 ± 0.01 µM. | 2102303-76-2 | |

| 108 | IC50 (PC-3) = 56.22 ± 0.54 nM; IC50 (SW-620) = 9.99 ± 0.86 nM. | 125035-83-8 | |

| 109 | IC50 (PC-3) = 2.06 ± 0.12 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 0.76 ± 0.04 µM. | 249512-77-4 | |

| 110 | IC50 (PC-3) = 2.50 ± 0.03 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 0.73 ± 0.03 µM. | 2251748-53-3 | |

| 111 | IC50 (PC-3) = 0.56 ± 0.04 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 0.18 ± 0.00 µM. | 155416-34-5 | |

| 112 | IC50 (PC-3) = 1.87 ± 0.03 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 1.04 ± 0.04 µM. | 105114-22-5 | |

| 113 | IC50 (PC-3) = 2.27 ± 0.06 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 0.81 ± 0.03 µM. | 1185908-87-5 | |

| 114 | IC50 (PC-3) = 0.69 ± 0.02 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 0.47 ± 0.02 µM. | 160256-54-2 | |

| 115 | IC50 (PC-3) >20 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = >20 µM. | 156582018(PubChem CID) | |

| 116 | IC50 (PC-3) = 0.77 ± 0.05 µM; IC50 (SW-620) = 0.02 ± 0.00 µM. | 187810-82-8 | |

| UCN-01 (117) | Entered clinical trials, but with poor targeting.IC50 (MCF-7) = 1.636 ± 0.281 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 1.034 ± 0.111 µM; | 112953-11-4 | [78,79,80,81,82,83] |

| lestaurtinib (118) | Entered clinical trials, but with poor targeting. | 111358-88-4 | [84,85,86,87] |

| midostaurin (119) | Midostaurin was developed and listed as a drug on the market, mainly for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia with a positive FLT3 mutation. | 120685-11-2 | [88,89,90] |

| 120 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.020 ± 0.010 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.235 ± 0.017 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 0.439 ±0.120 µM. | 120685-11-2 | [94] |

| 121 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.027 ± 0.000 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.122 ± 0.018 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 0.098 ±0.022 µM. | 2771013-95-5 | |

| 122 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.031 ± 0.000 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.257 ± 0.035 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 0.141 ±0.013 µM. | 2771013-97-7 | |

| 123 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.011 ± 0.000 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.121 ± 0.033 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 0.149 ±0.032 µM. | 2173322-11-5 | |

| 124 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.015 ± 0.001 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.018 ± 0.010 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 0.090 ±0.007 µM. | 2771013-94-4 | |

| 125 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.012 ± 0.001 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.072 ± 0.028 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 0.032 ±0.006 µM. | 2771013-96-6 | |

| 126 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.275 ± 0.009 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 43.530 ±0.750 µM. | 945260-14-0 | |

| 127 | IC50 (L-02) = 67.903 ±1.678 µM. | 2771014-05-0 | |

| 128 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.295 ± 0.005 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 59.807 ±0.248 µM. | 2771014-09-4 | |

| 129 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.128 ± 0.005 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 28.780 ±1.530 µM. | 137888-66-5(CAS number of racemate) | |

| 130 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.135 ± 0.004 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 8.740 ± 0.513 µM. | 2771014-03-8 | |

| 131 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.139 ± 0.012 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 4.432 ± 0.785 µM. | 2771014-07-2 | |

| 132 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.238 ± 0.014 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 23.32 ± 1.237 µM. | 155848-20-7 | |

| 133 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.635 ± 0.020 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 12.325 ±0.191 µM. | 2771014-04-9 | |

| 134 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.328 ± 0.022 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.183 ± 0.032 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 13.875 ±0.248 µM. | 2771014-08-3 | |

| 135 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.148 ± 0.004 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.621 ± 0.185 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 18.490 ±0.433 µM. | 137888-66-5(CAS number of racemate) | |

| 136 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.582 ± 0.072 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 8.635 ± 0.279 µM. | 2771014-02-7 | |

| 137 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.217 ± 0.016 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.021 ± 0.002 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 0.793 ±0.201 µM. | 2771014-06-1 | |

| 138 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.078 ±0.004 µM; IC50 (PATU-8988T) = 0.666 ± 0.055 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 97.800 ±0.297 µM. | 154589-96-5 | |

| 139 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.073 ± 0.006 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.029 ± 0.002 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 2.977 ± 0.405 µM. | 2771013-99-9 | |

| 140 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.061 ± 0.005 µM; IC50 (L-02) = 3.238 ± 0.030 µM. | 2771014-01-6 | |

| 141 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.091 ± 0.003 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.312 ± 0.045 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 0.245 ±0.007 µM. | 125035-81-6 | |

| 142 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.038 ± 0.006 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.014 ± 0.002 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 0.058 ±0.006 µM. | 2771013-98-8 | |

| 143 | IC50 (MV4-11) = 0.013 ± 0.001 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.016 ± 0.002 µM; IC50 (HCT-116) = 0.032 ±0.003 µM. | 2771014-00-5 | |

| spongosoritin A (145) | IC50 (A549) = 77.3 µM; IC50 (K562) = 24.2 µM. | / | [65] |

| spongosoritin B (146) | IC50 (A549) = 55.7 µM; IC50 (K562) = 28.5 µM. | / | |

| spongosoritin C (147) | IC50 (A549) = 61.2 µM; IC50 (K562) = 37.7 µM. | / | |

| spongosoritin D (148) | IC50 (A549) = 70.9 µM; IC50 (K562) = 54.2 µM. | / | |

| (+)-spondomine (149) | IC50 (K562) = 2.2 µM. | 2687275-02-9 | [97] |

| rhopaladin B (152) | Showed inhibitory activity on cyclin dependent kinase 4 and c-erbB-2 kinase, with IC50 of 12.5 and 7.4 μg/mL. | 212069-49-3 | [98] |

| hyrtinadine A (155) | IC50 (L1210) = 1 mg/mL; IC50 (KB) = 3 mg/mL; weak cytotoxicity to HCT116 and A2780 cancer cells (IC50 >10 µM). | 925253-33-4 | [99] |

| 156 | IC50 (HCT116) = 3.7 µM; IC50 (A2780) = 4.5 µM. | 1333469-91-2 | [100] |

| spiroindimicin B (157) | IC50 (B16) = 5 µg/mL; IC50 (H460) = 12 µg/mL; IC50 (CCRF-CEM) = 4 µg/mL. | 1380717-82-7 | [101] |

| spiroindimicin C (158) | IC50 (HepG2) = 6 µg/mL; IC50 (H460) = 15 µg/mL; | 1380717-83-8 | [101] |

| spiroindimicin D (159) | IC50 (HepG2) = 22 µg/mL; IC50 (B16) = 20 µg/mL; IC50 (H460) = 18 µg/mL. | 1380717-83-8 | |

| indimicin B (160) | Moderate cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cell line. | 1620987-80-5 | [102] |

| luteoalbusin A (161) | IC50 (SF-268) = 0.46 ± 0.05 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.23 ± 0.03 µM; IC50 (NCI-H460) = 1.15 ± 0.03 µM; IC50 (HepG2) = 0.91 ± 0.03 µM. | 1414774-32-5 | [103] |

| luteoalbusin B (162) | IC50 (SF-268) = 0.59 ± 0.03 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.25 ± 0.00 µM; IC50 (NCI-H460) = 1.31 ± 0.12 µM; IC50 (HepG2) = 1.29 ± 0.16 µM. | 1414774-33-6 | |

| T988A (163) | IC50 (SF-268) = 1.04 ± 0.03 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.91 ± 0.03 µM; IC50 (NCI-H460) = 5.60 ± 0.58 µM; IC50 (HepG2) = 3.52 ± 0.74 µM. | 823802-55-7 | |

| gliocladine C (164) | IC50 (SF-268) = 0.73 ± 0.05 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.23 ± 0.03 µM; IC50 (NCI-H460) = 6.57 ± 0.81 µM; IC50 (HepG2) = 0.53 ± 0.04 µM. | 871335-07-8 | |

| gliocladine D (165) | IC50 (SF-268) = 2.49 ± 0.07 µM; IC50 (MCF-7) = 0.65 ± 0.07 µM; IC50 (NCI-H460) = 17.78 ± 0.27 µM; IC50 (HepG2) = 2.03 ± 0.07 µM. | 871335-08-9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, M.; Bai, Z.; Xie, B.; Peng, R.; Du, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yan, S.; Xiao, X.; Qin, S. Marine-Derived Bisindoles for Potent Selective Cancer Drug Discovery and Development. Molecules 2024, 29, 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29050933

Xu M, Bai Z, Xie B, Peng R, Du Z, Liu Y, Zhang G, Yan S, Xiao X, Qin S. Marine-Derived Bisindoles for Potent Selective Cancer Drug Discovery and Development. Molecules. 2024; 29(5):933. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29050933

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Mengwei, Zhaofang Bai, Baocheng Xie, Rui Peng, Ziwei Du, Yan Liu, Guangshuai Zhang, Si Yan, Xiaohe Xiao, and Shuanglin Qin. 2024. "Marine-Derived Bisindoles for Potent Selective Cancer Drug Discovery and Development" Molecules 29, no. 5: 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29050933

APA StyleXu, M., Bai, Z., Xie, B., Peng, R., Du, Z., Liu, Y., Zhang, G., Yan, S., Xiao, X., & Qin, S. (2024). Marine-Derived Bisindoles for Potent Selective Cancer Drug Discovery and Development. Molecules, 29(5), 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29050933