Molecular Mechanisms of Microcystin Toxicity in Animal Cells

Abstract

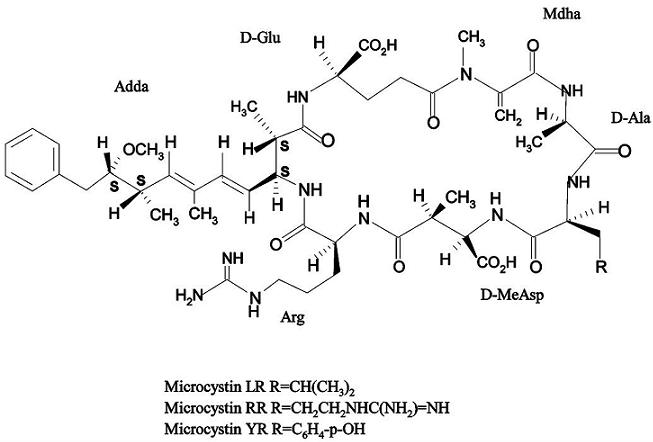

:1. Introduction

2. Cellular Uptake of MC

3. Toxicity Mechanisms

3.1. Interaction with Protein Phosphatases PP1 and PP2A

3.2. Regulation of Activity/Expression of Phosphoproteins

3.3. Oxidative Stress

3.4. Induction of Neutrophil-derived Chemokine

4. MC Biotransformation and Excretion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Amorim, A; Vasconcelos, V. Dynamics of microcystins in the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Toxicon 1999, 37, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard, C; Carpentier, A; Paillisson, J-M. Long-term dynamics and community structure of freshwater gastropods exposed to parasitism and other environmental stressors. Freshwater Biol 2008, 53, 470–484. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard, C; Poullain, V; Lance, E; Acou, A; Brient, L; Carpentier, A. Influence of toxic cyanobacteria on community structure and microcystin accumulation of freshwater molluscs. Environ. Pollut 2009, 157, 609–617. [Google Scholar]

- van Apeldoorn, ME; van Egmond, HP; Speijers, GJ; Bakker, GJ. Toxins of cyanobacteria. Mol. Nutr. Food Res 2007, 51, 7–60. [Google Scholar]

- McElhiney, J; Lawton, LA. Detection of the cyanobacterial hepatotoxins microcystins. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 2005, 203, 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Feurstein, D; Holst, K; Fischer, A; Dietrich, DR. Oatp-associated uptake and toxicity of microcystins in primary murine whole brain cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 2009, 234, 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Puerto, M; Pichardo, S; Jos, A; Camean, AM. Comparison of the toxicity induced by microcystin-RR and microcystin-YR in differentiated and undifferentiated Caco-2 cells. Toxicon 2009, 54, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, AI; Jos, A; Pichardo, S; Moreno, I; de Sotomayor, MA; Moyano, R; Blanco, A; Camean, AM. Time-dependent protective efficacy of Trolox (vitamin E analog) against microcystin-induced toxicity in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Environ. Toxicol 2009, 24, 563–579. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W; de la Cruz, AA; Rein, K; O'Shea, KE. Ultrasonically induced degradation of microcystin-LR and -RR: Identification of products, effect of pH, formation and destruction of peroxides. Environ. Sci. Technol 2006, 40, 3941–3946. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, K; Naito, S; Kondo, F; Ishikawa, N; Watanabe, MF; Suzuki, M; Harada, K-I. Stability of microcystins from cyanobacteria: Effect of light on decomposition and isomerization. Environ. Sci. Technol 1994, 28, 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- MacKintosh, C; Beattie, KA; Klumpp, S; Cohen, P; Codd, GA. Cyanobacterial microcystin-LR is a potent and specific inhibitor of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A from both mammals and higher plants. FEBS Lett 1990, 264, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Gulledgea, BM; Aggena, JB; Huangb, HB; Nairnc, AC; Chamberlin, AR. The microcystins and nodularins: Cyclic polypeptide inhibitors of PP1 and PP2A. Curr. Med. Chem 2002, 9, 1991–2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H; Zhang, J; Chen, Y; Zhu, Y. Microcystin-RR induces apoptosis in fish lymphocytes by generating reactive oxygen species and causing mitochondrial damage. Fish Physiol. Biochem 2008, 34, 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lankoff, A; Sochacki, J; Spoof, L; Meriluoto, J; Wojcik, A; Wegierek, A; Verschaeve, L. Nucleotide excision repair impairment by nodularin in CHO cell lines due to ERCC1/XPF inactivation. Toxicol. Lett 2008, 179, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki, H; Suganuma, M. Carcinogenic aspects of protein phosphatase 1 and 2A inhibitors. Prog. Mol. Subcell Biol 2009, 46, 221–254. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiwaki-Matsushima, R; Ohta, T; Nishiwaki, S; Suganuma, M; Kohyama, K; Ishikawa, T; Carmichael, WW; Fujiki, H. Liver tumor promotion by the cyanobacterial cyclic peptide toxin microcystin-LR. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol 1992, 118, 420–424. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, IR. Tumour promotion and liver injury caused by oral consumption of cyanobacteria. Environ. Toxicol. Water Qual 1991, 6, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Humpage, AR; Hardy, SJ; Moore, EJ; Froscio, SM; Falconer, IR. Microcystins (cyanobacterial toxins) in drinking water enhance the growth of aberrant crypt foci in the mouse colon. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2000, 61, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Milutinović, A; Živin, M; Zorc-Plesković, R; Sedmark, B; Šuput, D. Nephrotoxic effects of chronic administration of microcystins-LR and –YR. Toxicon 2003, 42, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Milutinović, A; Sedmark, B; Horvat-ŽnidarŠić, I; Šuput, D. Renal injuries induced by chronic intoxication with microcystins. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett 2002, 7, 139–141. [Google Scholar]

- Nobre, ACL; Jorge, MCM; Menezes, DB; Fonteles, MC; Monteiro, HSA. Effects of microcystin-LR in isolated perfused rat kidney. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res 1999, 32, 985–988. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, N; Van de Venter, M; Downing, TG; Shepard, EG; Gehringer, EG. The effect of intraperitoneally administered microcystin-LR on the gastrointestinal tract of Balb/c mice. Toxicon 2004, 43, 251–254. [Google Scholar]

- Zegura, B; Volcic, M; Lah, TT; Filipic, M. Different sensitivities of human colon adenocarcinoma (CaCo-2), astrocytoma (IPDDC-A2) and lymphoblastoid (NCNC) cell lines to microcystin-LR induced reactive oxygen species and DNA damage. Toxicon 2008, 52, 518–525. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, E; Andrade, M; Alverca, E; Pereira, P; Batoreu, MC; Jordan, P; Silva, MJ. Comparative study of the cytotoxic effect of microcistin-LR and purified extracts from M. aeruginosa on a kidney cell line. Toxicon 2009, 53, 487–495. [Google Scholar]

- Svircev, Z; Krstic, S; Miladinov-Mikov, M; Baltic, V; Vidovic, M. Freshwater cyanobacterial blooms and primary liver cancer epidemiological studies in Serbia. J. Environ. Sci. Health C Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev 2009, 27, 36–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, JM; Lopez-Rodas, V; Costas, E. Microcystins from tap water could be a risk factor for liver and colorectal cancer: A risk intensified by global change. Med. Hypotheses 2009, 72, 539–540. [Google Scholar]

- Ueno, Y; Nagata, S; Tsutsumi, T; Hasegawa, A; Watanabe, MF; Park, HD; Chen, GC; Chen, G; Yu, SZ. Detection of microcystins, a blue-green algal hepatotoxin, in drinking water sampled in Haimen and Fusui, endemic areas of primary liver cancer in China, by highly sensitive immunoassay. Carcinogenesis 1996, 17, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Herfindal, L; Selheim, F. Microcystin produces disparate effects on liver cells in a dose dependent manner. Mini Rev. Med. Chem 2006, 6, 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, LA; Moffitt, MC; Ginn, HP; Neilan, BA. The molecular genetics and regulation of cyanobacterial peptide hepatotoxin biosynthesis. Crit. Rev. Toxicol 2008, 38, 847–856. [Google Scholar]

- Tillett, D; Dittmann, E; Erhard, M; von Dohren, H; Borner, T; Neilan, BA. Structural organization of microcystin biosynthesis in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806: An integrated peptide-polyketide synthetase system. Chem. Biol 2000, 7, 753–764. [Google Scholar]

- Young, FM; Thomson, C; Metcalf, JS; Lucocq, JM; Codd, GA. Immunogold localisation of microcystins in cryosectioned cells of Microcystis. J. Struct. Biol 2005, 151, 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- Juttner, F; Luthi, H. Topology and enhanced toxicity of bound microcystins in Microcystis PCC 7806. Toxicon 2008, 51, 388–397. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, JE; Gronberg, L; Nygard, S; Slotte, JP; Meriluoto, JA. Hepatocellular uptake of 3H-dihydromicrocystin-LR, a cyclic peptide toxin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1990, 1025, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen, CD; Lu, H. Xenobiotic transporters: Ascribing function from gene knockout and mutation studies. Toxicol. Sci 2008, 101, 186–196. [Google Scholar]

- Trauner, M; Boyer, JL. Bile salt transporters: Molecular characterization, function, and regulation. Physiol. Rev 2003, 83, 633–671. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, WJ; Altheimer, S; Cattori, V; Meier, PJ; Dietrich, DR; Hagenbuch, B. Organic anion transporting polypeptides expressed in liver and brain mediate uptake of microcystin. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 2005, 203, 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Meier-Abt, F; Hammann-Hanni, A; Stieger, B; Ballatori, N; Boyer, JL. The organic anion transport polypeptide 1d1 (Oatp1d1) mediates hepatocellular uptake of phalloidin and microcystin into skate liver. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 2007, 218, 274–279. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H; Choudhuri, S; Ogura, K; Csanaky, IL; Lei, X; Cheng, X; Song, PZ; Klaassen, CD. Characterization of organic anion transporting polypeptide 1b2-null mice: Essential role in hepatic uptake/toxicity of phalloidin and microcystin-LR. Toxicol. Sci 2008, 103, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Maynes, JT; Luu, HA; Cherney, MM; Andersen, RJ; Williams, D; Holmes, CF; James, MN. Crystal structures of protein phosphatase-1 bound to motuporin and dihydromicrocystin-LA: Elucidation of the mechanism of enzyme inhibition by cyanobacterial toxins. J. Mol. Biol 2006, 356, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa, S; Matsushima, R; Watanabe, MF; Harada, K; Ichihara, A; Carmichael, WW; Fujiki, H. Inhibition of protein phosphatases by microcystins and nodularin associated with hepatotoxicity. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol 1990, 116, 609–614. [Google Scholar]

- Honkanen, RE; Zwiller, J; Moore, RE; Daily, SL; Khatra, BS; Dukelow, M; Boynton, AL. Characterization of microcystin-LR, a potent inhibitor of type 1 and type 2A protein phosphatases. J. Biol. Chem 1990, 265, 19401–19404. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, M; Luu, HA; McCready, TL; Williams, D; Andersen, RJ; Holmes, CF. Molecular mechanisms underlying he interaction of motuporin and microcystins with type-1 and type-2A protein phosphatases. Biochem. Cell Biol 1996, 74, 569–578. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, J; Huang, HB; Kwon, YG; Greengard, P; Nairn, AC; Kuriyan, J. Three-dimensional structure of the catalytic subunit of protein serine/threonine phosphatase-1. Nature 1995, 376, 745–753. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, JF; Holmes, CF. Molecular mechanisms underlying inhibition of protein phosphatases by marine toxins. Front. Biosci 1999, 4, D646–D658. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y; Xu, Y; Chen, Y; Jeffrey, PD; Chao, Y; Lin, Z; Li, Z; Strack, S; Stock, JB; Shi, Y. Structure of protein phosphatase 2A core enzyme bound to tumor-inducing toxins. Cell 2006, 127, 341–353. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, T; Nishiwaki, R; Yatsunami, J; Komori, A; Suganuma, M; Fujiki, H. Hyperphosphorylation of cytokeratins 8 and 18 by microcystin-LR, a new liver tumor promoter, in primary cultured rat hepatocytes. Carcinogenesis 1992, 13, 2443–2447. [Google Scholar]

- Wickstrom, ML; Khan, SA; Haschek, WM; Wyman, JF; Eriksson, JE; Schaeffer, DJ; Beasley, VR. Alterations in microtubules, intermediate filaments, and microfilaments induced by microcystin-LR in cultured cells. Toxicol. Pathol 1995, 23, 326–337. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer, IR; Yeung, DS. Cytoskeletal changes in hepatocytes induced by Microcystis toxins and their relation to hyperphosphorylation of cell proteins. Chem. Biol. Interact 1992, 81, 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, P; Moorhead, GB; Ye, R; Lees-Miller, SP. Protein phosphatases regulate DNA-dependent protein kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem 2001, 276, 18992–18998. [Google Scholar]

- Lankoff, A; Bialczyk, J; Dziga, D; Carmichael, WW; Lisowska, H; Wojcik, A. Inhibition of nucleotide excision repair (NER) by microcystin-LR in CHO-K1 cells. Toxicon 2006, 48, 957–965. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, RR; Keyse, SM; Moggs, JG; Wood, RD. Reversible protein phosphorylation modulates nucleotide excision repair of damaged DNA by human cell extracts. Nucl. Acid. Res 1996, 24, 433–440. [Google Scholar]

- Fladmark, KE; Brustugun, OT; Hovland, R; Boe, R; Gjertsen, BT; Zhivotovsky, B; Doskeland, SO. Ultrarapid caspase-3 dependent apoptosis induction by serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitors. Cell Death Differ 1999, 6, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Fladmark, KE; Brustugun, OT; Mellgren, G; Krakstad, C; Boe, R; Vintermyr, OK; Schulman, H; Doskeland, SO. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II is required for microcystin-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem 2002, 277, 2804–2811. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, WX; Ong, CN. Role of oxidative stress and mitochondrial changes in cyanobacteria-induced apoptosis and hepatotoxicity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett 2003, 220, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, WX; Shen, HM; Ong, CN. Critical role of reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial permeability transition in microcystin-induced rapid apoptosis in rat hepatocytes. Hepatology 2000, 32, 547–555. [Google Scholar]

- Krakstad, C; Herfindal, L; Gjertsen, BT; Boe, R; Vintermyr, OK; Fladmark, KE; Doskeland, SO. CaM-kinaseII-dependent commitment to microcystin-induced apoptosis is coupled to cell budding, but not to shrinkage or chromatin hypercondensation. Cell Death Differ 2006, 13, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, DG; Fry, AM. Nek2 kinase in chromosome instability and cancer. Cancer Lett 2006, 237, 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M; Satinover, DL; Brautigan, DL. Phosphorylation and functions of inhibitor-2 family of proteins. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 2380–2389. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, WY; Chen, JP; Wang, XM; Xu, LH. Altered expression of p53, Bcl-2 and Bax induced by microcystin-LR in vivo and in vitro. Toxicon 2005, 46, 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H-H; Cai, X; Shouse, GP; Piluso, LG; Liu, X. A specific PP2A regulatory subunit, B56[gamma], mediates DNA damage-induced dephosphorylation of p53 at Thr55. EMBO J 2007, 26, 402–411. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, ML; Wang, XF; Xu, LH. Alteration of proteins expression in apoptotic FL cells induced by MCLR. Environ. Toxicol 2008, 23, 451–458. [Google Scholar]

- Zegura, B; Zajc, I; Lah, TT; Filipic, M. Patterns of microcystin-LR induced alteration of the expression of genes involved in response to DNA damage and apoptosis. Toxicon 2008, 51, 615–623. [Google Scholar]

- Morselli, E; Galluzzi, L; Kroemer, G. Mechanisms of p53-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization. Cell Res 2008, 18, 708–710. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, SP; Ryan, TP; Searfoss, GH; Davis, MA; Hooser, SB. Chronic microcystin exposure induces hepatocyte proliferation with increased expression of mitotic and cyclin-associated genes in P53-deficient mice. Toxicol. Pathol 2008, 36, 190–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, SS; Bassik, MC; Suh, H; Nishino, M; Arroyo, JD; Hahn, WC; Korsmeyer, SJ; Roberts, TM. PP2A regulates BCL-2 phosphorylation and proteasome-mediated degradation at the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 23003–23012. [Google Scholar]

- Gehringer, MM. Microcystin-LR and okadaic acid-induced cellular effects: A dualistic response. FEBS Lett 2004, 557, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, M; Furukawa, T; Ikeda, R; Takumi, S; Nong, Q; Aoyama, K; Akiyama, S; Keppler, D; Takeuchi, T. Involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways in microcystin-LR-induced apoptosis after its selective uptake mediated by OATP1B1 and OATP1B3. Toxicol. Sci 2007, 97, 407–416. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H; Xie, P; Li, G; Hao, L; Xiong, Q. In vivo study on the effects of microcystin extracts on the expression profiles of proto-oncogenes (c-fos, c-jun and c-myc) in liver, kidney and testis of male Wistar rats injected i.v. with toxins. Toxicon 2009, 53, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Nong, Q; Komatsu, M; Izumo, K; Indo, HP; Xu, B; Aoyama, K; Majima, HJ; Horiuchi, M; Morimoto, K; Takeuchi, T. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in Microcystin-LR-induced cytogenotoxicity. Free Radic. Res 2007, 41, 1326–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Pichardo, S; Jos, A; Zurita, JL; Salguero, M; Camean, AM; Repetto, G. Acute and subacute toxic effects produced by microcystin-YR on the fish cell lines RTG-2 and PLHC-1. Toxicol. Vitro 2007, 21, 1460–1467. [Google Scholar]

- Sicinska, P; Bukowska, B; Michalowicz, J; Duda, W. Damage of cell membrane and antioxidative system in human erythrocytes incubated with microcystin-LR in vitro. Toxicon 2006, 47, 387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, WX; Shen, HM; Ong, CN. Pivotal role of mitochondrial Ca(2+) in microcystin-induced mitochondrial permeability transition in rat hepatocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2001, 285, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, D; Lu, Y; Wei, Y; Liu, Y; Shen, P. The role of ROS in microcystin-LR-induced hepatocyte apoptosis and liver injury in mice. Toxicology 2007, 232, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y; Weng, D; Li, F; Zou, X; Young, DO; Ji, J; Shen, P. Involvement of JNK regulation in oxidative stress-mediated murine liver injury by microcystin-LR. Apoptosis 2008, 13, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, T; Xie, P; Liu, Y; Li, G; Xiong, Q; Hao, L; Li, H. The profound effects of microcystin on cardiac antioxidant enzymes, mitochondrial function and cardiac toxicity in rat. Toxicology 2009, 257, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y; Sheng, J; Sha, J; Han, X. The toxic effects of microcystin-LR on the reproductive system of male rats in vivo and in vitro. Reproduct. Toxicol 2008, 26, 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, M. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem. J 1999, 341, 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, P; Scorrano, L; Colonna, R; Petronilli, V; Di Lisa, F. Mitochondria and cell death. Mechanistic aspects and methodological issues. Eur. J. Biochem 1999, 264, 687–701. [Google Scholar]

- Lemasters, JJ; Nieminen, AL; Qian, T; Trost, LC; Elmore, SP; Nishimura, Y; Crowe, RA; Cascio, WE; Bradham, CA; Brenner, DA; Herman, B. The mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death: A common mechanism in necrosis, apoptosis and autophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1366, 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- La-Salete, R; Oliveira, MM; Palmeira, CA; Almeida, J; Peixoto, FP. Mitochondria a key role in microcystin-LR kidney intoxication. J. Appl. Toxicol 2008, 28, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mikhailov, A; Härmälä-Braskén, A-S; Hellman, J; Meriluoto, J; Eriksson, JE. Identification of ATP-synthase as a novel intracellular target for microcystin-LR. Chem. Biol. Interact 2003, 142, 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T; Cui, J; Liang, Y; Xin, X; Young, DO; Chen, C; Shen, P. Identification of human liver mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase as a potential target for microcystin-LR. Toxicology 2006, 220, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, AI; Jos, A; Pichardo, S; Moreno, I; Camean, AM. Protective role of vitamin E on the microcystin-induced oxidative stress in tilapia fish (Oreochromis niloticus). Environ. Toxicol. Chem 2008, 27, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Babior, BM. Phagocytes and oxidative stress. Am. J. Med 2000, 109, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, WW; Azevedo, SM; An, JS; Molica, RJ; Jochimsen, EM; Lau, S; Rinehart, KL; Shaw, GR; Eaglesham, GK. Human fatalities from cyanobacteria: Chemical and biological evidence for cyanotoxins. Environ. Health Perspect 2001, 109, 663–668. [Google Scholar]

- Jochimsen, EM; Carmichael, WW; An, JS; Cardo, DM; Cookson, ST; Holmes, CE; Antunes, MB; Filho, DAM; Lyra, TM; Barreto, VS; Azevedo, SM; Jarvis, WR. Liver failure and death after exposure to microcystins at a hemodialysis center in Brazil. N. Engl. J. Med 1998, 338, 873–878. [Google Scholar]

- Pouria, S; de Andrade, A; Barbosa, J; Cavalcanti, RL; Barreto, VT; Ward, CJ; Preiser, W; Poon, GK; Neild, GH; Codd, GA. Fatal microcystin intoxication in haemodialysis unit in Caruaru, Brazil. Lancet 1998, 352, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kujbida, P; Hatanaka, E; Vinolo, MA; Waismam, K; Cavalcanti, DM; Curi, R; Farsky, SH; Pinto, E. Microcystins -LA, -YR, and -LR action on neutrophil migration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2009, 382, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kujbida, P; Hatanaka, E; Campa, A; Curi, R; Farsky, SHP; Pinto, E. Analysis of chemokines and reactive oxygen species formation by rat and human neutrophils induced by microcystin-LA, -YR and -LR. Toxicon 2008, 51, 1274–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, F; Ikai, Y; Oka, H; Okumura, M; Ishikawa, N; Harada, K; Matsuura, K; Murata, H; Suzuki, M. Formation, characterization, and toxicity of the glutathione and cysteine conjugates of toxic heptapeptide microcystins. Chem. Res. Toxicol 1992, 5, 591–596. [Google Scholar]

- Pflugmacher, S; Wiegand, C; Oberemm, A; Beattie, KA; Krause, E; Codd, GA; Steinberg, CEW. Identification of an enzymatically formed glutathione conjugate of the cyanobacterial hepatotoxin microcystin-LR: The first step of detoxication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA): Gen. Subj 1998, 1425, 527–533. [Google Scholar]

- Zegura, B; Lah, TT; Filipic, M. Alteration of intracellular GSH levels and its role in microcystin-LR-induced DNA damage in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. Mutat. Res 2006, 611, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, JD; Flanagan, JU; Jowsey, IR. Glutathione transferases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 2005, 45, 51–88. [Google Scholar]

- Konishi, T; Kato, K; Araki, T; Shiraki, K; Takagi, M; Tamaru, Y. A new class of glutathione S-transferase from the hepatopancreas of the red sea bream Pagrus major. Biochem. J 2005, 388, 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G; Xie, P; Fu, J; Hao, L; Xiong, Q; Li, H. Microcystin-induced variations in transcription of GSTs in an omnivorous freshwater fish, goldfish. Aquat. Toxicol 2008, 88, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J; Xie, P. The acute effects of microcystin LR on the transcription of nine glutathione S-transferase genes in common carp Cyprinus carpio L. Aquat. Toxicol 2006, 80, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L; Liang, XF; Liao, WQ; Lei, LM; Han, BP. Structural and functional characterization of microcystin detoxification-related liver genes in a phytoplanktivorous fish, Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C: Toxicol. Pharmacol 2006, 144, 216–227. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey, BH; Epel, D. A multixenobiotic transporter in Urechis caupo embryos: Protection from pesticides? Mar. Environ. Res 1995, 39, 299–302. [Google Scholar]

- Bard, SM. Multixenobiotic resistance as a cellular defense mechanism in aquatic organisms. Aquat. Toxicol 2000, 48, 357–389. [Google Scholar]

- Ame, MV; Baroni, MV; Galanti, LN; Bocco, JL; Wunderlin, DA. Effects of microcystin-LR on the expression of P-glycoprotein in Jenynsia multidentata. Chemosphere 2009, 74, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Contardo-Jara, V; Pflugmacher, S; Wiegand, C. Multi-xenobiotic-resistance a possible explanation for the insensitivity of bivalves towards cyanobacterial toxins. Toxicon 2008, 52, 936–943. [Google Scholar]

| MC toxicity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Activity | Biological function | Presence of MC | Experimental approach | References |

| PP1, PP2A | serine/threonine protein phosphatase | regulation of protein activity | inhibition of activity | MC-PP interactions | [11,42] |

| DNA-PK | serine/threonine protein kinase | DNA repair | decrease activity | activity of DNA repair synthesis from cell extracts and purified DNA-PK | [49,51] |

| CaMKII | serine/threonine protein kinase | cell signalling | increase in activity | exposure of primary hepatocytes to MC | [56] |

| NeK2 | serine/threonine protein kinase | cell signaling | increase in activity | activity of purified NeK2:PP1 complex | [58] |

| P53 | transcription factor | cell cycle, tumor supression | increase of protein/gene expression | exposure of HepG2, FL cell lines, primary hepatocytes and in vivo liver tissues to MC | [59,61,62] |

| Bcl-2 | regulation of mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel (MAC) | mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, apoptosis | decrease of protein/gene expression | exposure of primary hepatocytes, in vivo liver tissues and FL cells to MC | [59,61] |

| MAPKs | serine/threonine protein kinase | signal transduction, cell proliferation and differentiation | increase of gene expression | exposure of HEK293-OATP1B3 cell line to MC | [67] |

| NADPH oxidase | electron transfer to superoxide | production of ROS | increase of gene expression | exposure of HepG2 cell line to MC | [69] |

| Bax, Bid | regulation of mitochondrial apoptosis-induced channel (MAC) | mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, apoptosis | increase of protein expression | in vivo exposure of liver tissues to MC | [73] |

| JNK | MAPK | signal transduction, cell proliferation and differentiation | increase in protein expression | in vivo exposure of liver tissues to MC | [74] |

| IL-8, CINC-2αβ, L-selectin, β2-integrin | chemotactic cytokines | chemotaxis, inflammatory reactions | increase in protein/gene expression | in vitro exposure of neutrohils to MC | [88,89] |

| OATP | plasma membrane transporter | transport of organic anions | nd (a) | exposure of transfected Xenopus laevis oocytes and Oatp1b2-null mice to MC | [36,38] |

| GST | gluthatione S-transferase | metabolism of endogenous compounds and xenobiotics | differential expression of GST genes | in vivo exposure of fish liver tissues to MC | [96,97] |

| P-glycoprotein | plasma membrane transporter | cellular excretion of cytotoxic compounds | increase of gene expression and protein activity | in vivo exposure of fish liver, gills and brain tissues; fresh water mussel to MC | [100,101] |

© 2010 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Campos, A.; Vasconcelos, V. Molecular Mechanisms of Microcystin Toxicity in Animal Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 268-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11010268

Campos A, Vasconcelos V. Molecular Mechanisms of Microcystin Toxicity in Animal Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2010; 11(1):268-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11010268

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampos, Alexandre, and Vitor Vasconcelos. 2010. "Molecular Mechanisms of Microcystin Toxicity in Animal Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 11, no. 1: 268-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11010268

APA StyleCampos, A., & Vasconcelos, V. (2010). Molecular Mechanisms of Microcystin Toxicity in Animal Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 11(1), 268-287. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11010268