Are the Effects of the Cholera Toxin and Isoproterenol on Human Keratinocytes’ Proliferative Potential Dependent on Whether They Are Co-Cultured with Human or Murine Fibroblast Feeder Layers?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. An Optimal Combination of Feeder Layer Type and of cAMP Inducer Type on Cultured Human Keratinocytes’ Proliferative Potential Was Not Detected in the Early Passages

2.2. Co-Culturing Human Keratinocytes with iHFL Rather Than i3T3FL Results in an Increased Proliferative Potential in the Early Passages

2.3. Culturing Human Keratinocytes with Either ISO- or CT-Supplemented Medium Does Not Significantly Influence Proliferative Potential in the Early Passages

2.4. Culturing Human Keratinocytes with Either cISO- or rISO-Supplemented Medium Does Not Significantly Influence Proliferative Potential in the Early Passages

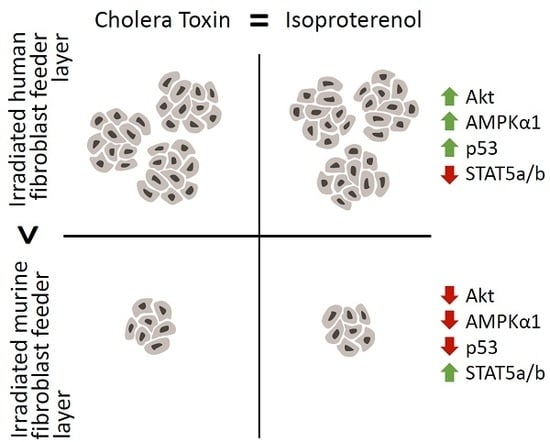

2.5. The Increased Growth Rate and Clonogenicity Observed When Keratinocytes Are Co-Cultured with iHFL Rather Than i3T3FL Could Be Explained by Differential Activation of Key Signaling Pathways

2.6. Perspectives

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Ethical Considerations

3.2. Cell Populations

3.3. cAMP Accumulation Inducing Agents

3.4. Feeder Layers

3.5. Keratinocyte Isolation

3.6. Keratinocyte Primoculture (P0)

3.7. Keratinocyte Subculture

3.8. Keratinocyte Cryopreservation and Thawing

3.9. Keratinocytes’ Proliferative Potential Proxies

3.10. Kinase Phosphorylation Profile Assays

3.11. Statistical Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3T3 | Swiss murine embryonic fibroblast cell line |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| AMPKα1 | Adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase α1 |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| cISO | Clinical-grade ISO |

| ckDME-Ham | Complete keratinocyte culture medium (cAMP inducer-free) |

| CT | Cholera toxin |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| GMP | Good manufacturing practice |

| i3T3 | Irradiated Swiss murine embryonic fibroblasts |

| i3T3FL | Irradiated Swiss murine embryonic fibroblast feeder layer |

| iFL | Irradiated feeder layer |

| iHLF | Irradiated human dermal fibroblast feeder layer |

| ISO | Isoproterenol |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| rISO | Research-grade ISO |

| STAT5 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 |

Appendix A

| Female Subjects (Age) | Anatomical Site | Cryopreservation |

|---|---|---|

| s1 (26 y/o) | Breast reduction tissue | * Cryopreserved |

| s2 (67 y/o) | Face-lift tissue | * Cryopreserved |

| s3 (65 y/o) | Breast reduction tissue | Never cryopreserved |

| s4 (62 y/o) | Face-lift tissue | Never cryopreserved |

Appendix B

Media and Solutions

- Complete keratinocyte culture medium (ckDME-Ham): Keratinocytes were cultured in three parts Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and one part Ham’s F12 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) mixture with 5% v/v of inactivated FetalClone II serum (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA). Additionally, it contained 3.07 g/L of NaHCO3 (J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA), 24.3 mg/L of adenine (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 μg/mL of insulin (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng/mL of epidermal growth factor (EGF; Austral Biologicals, San Ramon, CA, USA), 0.4 μg/mL of hydrocortisone (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA), 100 IU/mL of penicillin G (Sigma-Aldrich), 25 μg/mL of gentamicin (Galenova, Saint-Hyacinthe, QC, Canada), and either ISO or CT (see Section 3.4).

- Cryopreservation medium: Keratinocyte populations s1 and s2, and irradiated foreskin dermal fibroblasts were cryopreserved in inactivated fetal calf serum (HyClone) containing 10% v/v of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich).

- Trypsin/EDTA solution: Keratinocytes and fibroblasts were detached from culture flasks and dissociated with a phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution comprising 0.05% w/v of porcine trypsin 1–250 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.01% w/v of ethylenediaminetretraacetic acid (EDTA; J.T. Baker), 2.8 mM of d-glucose (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), 100 IU/mL of penicillin G (Sigma-Aldrich), 25 μg/mL of gentamicin (Galenova), and 0.00075% w/v of phenol red (J.T. Baker).

- Transport medium: Tissue samples from elective surgeries were transported from the clinic to our lab in 10% v/v of fetal calf serum in high glucose (4.5 g/L) DMEM (containing sodium pyruvate and L-glutamine; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 0.5 μg/mL of amphotericin B (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Saint-Laurent, QC, Canada), 100 IU/mL of penicillin G (Sigma-Aldrich), and 25 μg/mL of gentamicin (Galenova).

- Washing solution: Tissue samples were washed in 1× PBS containing 0.5 μg/mL of amphotericin B (Bristol-Myers Squibb), 100 IU/mL of penicillin G (Sigma-Aldrich), and 25 μg/mL of gentamicin (Galenova).

- Thermolysin dissociation solution: The epidermis and the dermis were dissociated after skin specimens were incubated in a 500 μg/mL of thermolysin (Sigma-Aldrich) in a 0.01 M 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES; MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) solution containing 0.67 mM of KCL (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.14 M of NaCl (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 1 mM of CaCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich).

- Lysis buffer: Whole cell protein extracts were prepared by homogenizing keratinocytes in a buffer containing 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada), 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4; Bio Basic, Markham, ON, Canada), 150 mM NaCl (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 mM ethylenediaminetretraacetic acid (EDTA; J.T. Baker), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Sigma-Aldrich), and protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, QC, Canada).

References

- Rheinwald, J.G.; Green, H. Formation of a keratinizing epithelium in culture by a cloned cell line derived from a teratoma. Cell 1975, 6, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paré, B.; Touzel-Deschênes, L.; Lamontagne, R.; Lamarre, M.-S.; Scott, F.-D.; Khuong, H.T.; Dion, P.A.; Bouchard, J.-P.; Gould, P.; Rouleau, G.A. Early detection of structural abnormalities and cytoplasmic accumulation of TDP-43 in tissue-engineered skins derived from ALS patients. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2015, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piskin, G.; Sylva-Steenland, R.M.; Bos, J.D.; Teunissen, M.B. In vitro and in situ expression of IL-23 by keratinocytes in healthy skin and psoriasis lesions: Enhanced expression in psoriatic skin. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 1908–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purdie, K.J.; Lambert, S.R.; Teh, M.T.; Chaplin, T.; Molloy, G.; Raghavan, M.; Kelsell, D.P.; Leigh, I.M.; Harwood, C.A.; Proby, C.M. Allelic imbalances and microdeletions affecting the PTPRD gene in cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas detected using single nucleotide polymorphism microarray analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2007, 46, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallico, G.G., III; O’Connor, N.E.; Compton, C.C.; Kehinde, O.; Green, H. Permanent coverage of large burn wounds with autologous cultured human epithelium. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984, 311, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, N.; Mulliken, J.; Banks-Schlegel, S.; Kehinde, O.; Green, H. Grafting of burns with cultured epithelium prepared from autologous epidermal cells. Lancet 1981, 317, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerid, S.; Darwiche, S.E.; Berger, M.M.; Applegate, L.A.; Benathan, M.; Raffoul, W. Autologous keratinocyte suspension in platelet concentrate accelerates and enhances wound healing—A prospective randomized clinical trial on skin graft donor sites: Platelet concentrate and keratinocytes on donor sites. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2013, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, F.; Kolybaba, M.; Allen, P. The use of cultured epithelial autograft in the treatment of major burn injuries: A critical review of the literature. Burns 2006, 32, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blok, C.S.; Vink, L.; Boer, E.M.; Montfrans, C.; Hoogenband, H.M.; Mooij, M.C.; Gauw, S.A.; Vloemans, J.A.; Bruynzeel, I.; Kraan, A. Autologous skin substitute for hard-to-heal ulcers: Retrospective analysis on safety, applicability, and efficacy in an outpatient and hospitalized setting. Wound Repair Regener. 2013, 21, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, S.T.; Simpson, P.S.; Rieman, M.T.; Warner, P.M.; Yakuboff, K.P.; Bailey, J.K.; Nelson, J.K.; Fowler, L.A.; Kagan, R.J. Randomized, paired-site comparison of autologous engineered skin substitutes and split-thickness skin graft for closure of extensive, full-thickness burns. J. Burn Care Res. 2017, 38, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golinski, P.; Menke, H.; Hofmann, M.; Valesky, E.; Butting, M.; Kippenberger, S.; Bereiter-Hahn, J.; Bernd, A.; Kaufmann, R.; Zoeller, N.N. Development and characterization of an engraftable tissue-cultured skin autograft: Alternative treatment for severe electrical injuries? Cells Tissues Organs 2014, 200, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boa, O.; Cloutier, C.B.; Genest, H.; Labbé, R.; Rodrigue, B.; Soucy, J.; Roy, M.; Arsenault, F.; Ospina, C.E.; Dubé, N. Prospective study on the treatment of lower-extremity chronic venous and mixed ulcers using tissue-engineered skin substitute made by the self-assembly approach. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2013, 26, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, S.T.; Supp, A.P.; Wickett, R.R.; Hoath, S.B.; Warden, G.D. Assessment with the dermal torque meter of skin pliability after treatment of burns with cultured skin substitutes. J. Burn Care Rehabilit. 2000, 21, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auxenfans, C.; Thépot, A.; Justin, V.; Hautefeuille, A.; Shahabeddin, L.; Damour, O.; Hainaut, P. Characterisation of human fibroblasts as keratinocyte feeder layer using p63 isoforms status. Bio-Med. Mater. Eng. 2009, 19, 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Bisson, F.; Rochefort, É.; Lavoie, A.; Larouche, D.; Zaniolo, K.; Simard-Bisson, C.; Damour, O.; Auger, F.A.; Guérin, S.L.; Germain, L. Irradiated human dermal fibroblasts are as efficient as mouse fibroblasts as a feeder layer to improve human epidermal cell culture lifespan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 4684–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock, A.J.; Higham, M.C.; MacNeil, S. Use of human fibroblasts in the development of a xenobiotic-free culture and delivery system for human keratinocytes. Tissue Eng. 2006, 12, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jubin, K.; Martin, Y.; Lawrence-Watt, D.; Sharpe, J. A fully autologous co-culture system utilising non-irradiated autologous fibroblasts to support the expansion of human keratinocytes for clinical use. Cytotechnology 2011, 63, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bisson, F.; Paquet, C.; Bourget, J.M.; Zaniolo, K.; Rochette, P.J.; Landreville, S.; Damour, O.; Boudreau, F.; Auger, F.A.; Guérin, S.L. Contribution of Sp1 to telomerase expression and activity in skin keratinocytes cultured with a feeder layer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 230, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, H. Cyclic amp in relation to proliferation of the epidermal cell: A new view. Cell 1978, 15, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, R.; Yamato, M.; Murakami, D.; Kondo, M.; Yang, J.; Ohki, T.; Nishida, K.; Kohno, C.; Okano, T. Preparation of keratinocyte culture medium for the clinical applications of regenerative medicine. J. Tissue Eng. Regener. Med. 2011, 5, e63–e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoubay-Benallaoua, D.; Pécha, F.; Goldschmidt, P.; Fialaire-Legendre, A.; Chaumeil, C.; Laroche, L.; Borderie, V.M. Effects of isoproterenol and cholera toxin on human limbal epithelial cell cultures. Curr. Eye Res. 2012, 37, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrandon, Y.; Green, H. Cell size as a determinant of the clone-forming ability of human keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 5390–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrandon, Y.; Green, H. Three clonal types of keratinocyte with different capacities for multiplication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 2302–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thepot, A.; Desanlis, A.; Venet, E.; Thivillier, L.; Justin, V.; Morel, A.; Defraipont, F.; Till, M.; Krutovskikh, V.; Tommasino, M. Assessment of transformed properties in vitro and of tumorigenicity in vivo in primary keratinocytes cultured for epidermal sheet transplantation. J. Skin Cancer 2011, 2011, 936546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krunic, D.; Moshir, S.; Greulich-Bode, K.M.; Figueroa, R.; Cerezo, A.; Stammer, H.; Stark, H.-J.; Gray, S.G.; Nielsen, K.V.; Hartschuh, W. Tissue context-activated telomerase in human epidermis correlates with little age-dependent telomere loss. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1792, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hirsch, T.; Rothoeft, T.; Teig, N.; Bauer, J.W.; Pellegrini, G.; De Rosa, L.; Scaglione, D.; Reichelt, J.; Klausegger, A.; Kneisz, D. Regeneration of the entire human epidermis using transgenic stem cells. Nature 2017, 551, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson-Gadais, B.; Fugère, C.; Paquet, C.; Leclerc, S.; Lefort, N.R.; Germain, L.; Guérin, S.L. The feeder layer-mediated extended lifetime of cultured human skin keratinocytes is associated with altered levels of the transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006, 206, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, M.; De Santis, M.C.; Braccini, L.; Gulluni, F.; Hirsch, E. PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and cancer: An updated review. Ann. Med. 2014, 46, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromberg, J.; Darnell, J.E. The role of stats in transcriptional control and their impact on cellular function. Oncogene 2000, 19, 2468–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calò, V.; Migliavacca, M.; Bazan, V.; Macaluso, M.; Buscemi, M.; Gebbia, N.; Russo, A. Stat proteins: From normal control of cellular events to tumorigenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003, 197, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couture, C.; Desjardins, P.; Zaniolo, K.; Germain, L.; Guérin, S.L. Enhanced wound healing of tissue-engineered human corneas through altered phosphorylation of the CREB and Akt signal transduction pathways. Acta Biomater. 2018, 73, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazel, A.; Ramphal, P.; Rosdy, M.; Tornier, C.; Hosein, N.; Lee, B.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Blumenberg, M. Transcriptional profiling of epidermal keratinocytes: Comparison of genes expressed in skin, cultured keratinocytes, and reconstituted epidermis, using large DNA microarrays. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003, 121, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Choi, D.-K.; Kim, C.D.; Ahn, G.-B.; Yoon, T.Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, J.Y. Comparison of gene expression profiles between keratinocytes, melanocytes and fibroblasts. Ann. Dermatol. 2013, 25, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simard-Bisson, C.; Bidoggia, J.; Larouche, D.; Guérin, S.L.; Blouin, R.; Hirai, S.-I.; Germain, L. A role for dlk in microtubule reorganization to the cell periphery and in the maintenance of desmosomal and tight junction integrity. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, L.; Rouabhia, M.; Guignard, R.; Carrier, L.; Bouvard, V.; Auger, F. Improvement of human keratinocyte isolation and culture using thermolysin. Burns 1993, 19, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wobbrock, J.O.; Findlater, L.; Gergle, D.; Higgins, J.J. The aligned rank transform for nonparametric factorial analyses using only anova procedures. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011; pp. 143–146. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth, R.V. Least-squares means: The R package lsmeans. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 69, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario-Martinez, H. Phia: Post-Hoc Interaction Analysis. R Package Version 0.1–3. 2013. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ARTool/index.html (accessed on 21 July 2018).

| 1 Significant Factor Effects and Interactions | Keratinocytes’ Proliferative Potential Proxies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Population Doublings | Population Mean Cell Size (μm) | Colony-Forming Efficiency (% of Holoclones) | |

| Feeder layer type | iHFL > i3T3FL | iHFL > i3T3FL | iHFL > i3T3FL |

| 0.93 > 0.66 | 16.32 > 15.85 | 5.85 > 1.81 | |

| cAMP inducer type | cISO > CT | ||

| 4.56 > 3.07 | |||

| Passage number | (P1 = P2) > P3 | P1 < (P2 = P3) | P1 > P2 > P3 |

| (0.89 = 0.83) > 0.66 | 15.56 < (16.20 = 16.50) | 5.58 > 4.01 > 2.00 | |

| 2 Feeder layer type × passage number | iHFL − i3T3FL: P1 < (P2 = P3) | iHFL − i3T3FL: P1 > (P2 = P3) | |

| 0.11 < (0.31 = 0.38) | 1.47 > (0.07 = −0.11) | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cortez Ghio, S.; Cantin-Warren, L.; Guignard, R.; Larouche, D.; Germain, L. Are the Effects of the Cholera Toxin and Isoproterenol on Human Keratinocytes’ Proliferative Potential Dependent on Whether They Are Co-Cultured with Human or Murine Fibroblast Feeder Layers? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19082174

Cortez Ghio S, Cantin-Warren L, Guignard R, Larouche D, Germain L. Are the Effects of the Cholera Toxin and Isoproterenol on Human Keratinocytes’ Proliferative Potential Dependent on Whether They Are Co-Cultured with Human or Murine Fibroblast Feeder Layers? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018; 19(8):2174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19082174

Chicago/Turabian StyleCortez Ghio, Sergio, Laurence Cantin-Warren, Rina Guignard, Danielle Larouche, and Lucie Germain. 2018. "Are the Effects of the Cholera Toxin and Isoproterenol on Human Keratinocytes’ Proliferative Potential Dependent on Whether They Are Co-Cultured with Human or Murine Fibroblast Feeder Layers?" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19, no. 8: 2174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19082174

APA StyleCortez Ghio, S., Cantin-Warren, L., Guignard, R., Larouche, D., & Germain, L. (2018). Are the Effects of the Cholera Toxin and Isoproterenol on Human Keratinocytes’ Proliferative Potential Dependent on Whether They Are Co-Cultured with Human or Murine Fibroblast Feeder Layers? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(8), 2174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19082174