Disruption of Circadian Rhythms: A Crucial Factor in the Etiology of Infertility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

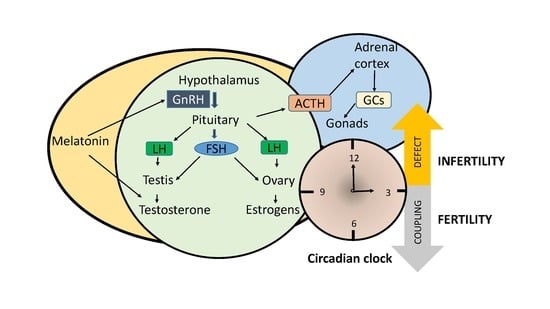

2. How Fertility Is Influenced by Hormones and Clock Genes?

2.1. Gonadotropins

2.2. Estrogens and Androgens

2.3. Glucocorticoids

2.4. Melatonin

3. Genetic Models of Clock Genes and Fertility

3.1. Female Fertility

3.2. Male Fertility

3.3. Circadian Clock and Sexual Development

4. Effect of Clock Gene Mutation in Humans

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dickmeis, T.; Weger, B.D.; Weger, M. The circadian clock and glucocorticoids--interactions across many time scales. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2013, 380, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kume, K.; Zylka, M.J.; Sriram, S.; Shearman, L.P.; Weaver, D.R.; Jin, X.; Maywood, E.S.; Hastings, M.H.; Reppert, S.M. Mcry1 and mcry2 are essential components of the negative limb of the circadian clock feedback loop. Cell 1999, 98, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nader, N.; Chrousos, G.P.; Kino, T. Interactions of the circadian clock system and the hpa axis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 21, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Partch, C.L.; Green, C.B.; Takahashi, J.S. Molecular architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Trends Cell Biol. 2014, 24, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kennaway, D.J.; Boden, M.J.; Varcoe, T.J. Circadian rhythms and fertility. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2012, 349, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sen, A.; Hoffmann, H.M. Role of core circadian clock genes in hormone release and target tissue sensitivity in the reproductive axis. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2020, 501, 110655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Taylor, M.J.; Cohen, E.; Hanna, N.; Mota, S. Circadian clock, time-restricted feeding and reproduction. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalantaridou, S.N.; Makrigiannakis, A.; Zoumakis, E.; Chrousos, G.P. Stress and the female reproductive system. J. Reprod Immunol. 2004, 62, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.J.; Aeschbach, D.; Scheer, F.A. Circadian system, sleep and endocrinology. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2012, 349, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minnetti, M.; Hasenmajer, V.; Pofi, R.; Venneri, M.A.; Alexandraki, K.I.; Isidori, A.M. Fixing the broken clock in adrenal disorders: Focus on glucocorticoids and chronotherapy. J. Endocrinol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D.N.; Whirledge, S. Stress and the hpa axis: Balancing homeostasis and fertility. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, J.; Kuohung, W. Impact of circadian rhythms on female reproduction and infertility treatment success. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2019, 26, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boden, M.J.; Kennaway, D.J. Circadian rhythms and reproduction. Reproduction 2006, 132, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Angelousi, A.; Kassi, E.; Nasiri-Ansari, N.; Weickert, M.O.; Randeva, H.; Kaltsas, G. Clock genes alterations and endocrine disorders. Eur J. Clin. Invest. 2018, 48, e12927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miller, B.H.; Olson, S.L.; Turek, F.W.; Levine, J.E.; Horton, T.H.; Takahashi, J.S. Circadian clock mutation disrupts estrous cyclicity and maintenance of pregnancy. Curr Biol. 2004, 14, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harter, C.J.L.; Kavanagh, G.S.; Smith, J.T. The role of kisspeptin neurons in reproduction and metabolism. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 238, R173–R183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yeo, S.H.; Colledge, W.H. The role of kiss1 neurons as integrators of endocrine, metabolic, and environmental factors in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Irwig, M.S.; Fraley, G.S.; Smith, J.T.; Acohido, B.V.; Popa, S.M.; Cunningham, M.J.; Gottsch, M.L.; Clifton, D.K.; Steiner, R.A. Kisspeptin activation of gonadotropin releasing hormone neurons and regulation of kiss-1 mrna in the male rat. Neuroendocrinology 2004, 80, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messager, S.; Chatzidaki, E.E.; Ma, D.; Hendrick, A.G.; Zahn, D.; Dixon, J.; Thresher, R.R.; Malinge, I.; Lomet, D.; Carlton, M.B.; et al. Kisspeptin directly stimulates gonadotropin-releasing hormone release via g protein-coupled receptor 54. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 1761–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sairam, M.R.; Krishnamurthy, H. The role of follicle-stimulating hormone in spermatogenesis: Lessons from knockout animal models. Arch. Med. Res. 2001, 32, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquelin, A.; Desjardins, C. Luteinizing hormone and testosterone secretion in young and old male mice. Am. J. Physiol. 1982, 243, E257–E263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, H.H.; Ratnam, S.S. The lh surge in humans: Its mechanism and sex difference. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 1988, 2, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Watanabe, K.; Matsumura, R.; Anayama, N.; Miyamoto, A.; Miyazaki, H.; Miyazaki, K.; Shimizu, T.; Akashi, M. Involvement of the luteinizing hormone surge in the regulation of ovary and oviduct clock gene expression in mice. Genes Cells 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chianese, R.; Cobellis, G.; Chioccarelli, T.; Ciaramella, V.; Migliaccio, M.; Fasano, S.; Pierantoni, R.; Meccariello, R. Kisspeptins, estrogens and male fertility. Curr Med. Chem 2016, 23, 4070–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.A.; Grant, L.K.; Gooley, J.J.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Czeisler, C.A.; Lockley, S.W. Endogenous circadian regulation of female reproductive hormones. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 6049–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, S.L.; Bell, R. Androgen physiology. Semin Reprod Med. 2006, 24, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P.S.; Nanjappa, M.K.; Ko, C.; Prins, G.S.; Hess, R.A. Estrogens in male physiology. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 995–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naftolin, F.; Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Horvath, T.L.; Zsarnovszky, A.; Demir, N.; Fadiel, A.; Leranth, C.; Vondracek-Klepper, S.; Lewis, C.; Chang, A.; et al. Estrogen-induced hypothalamic synaptic plasticity and pituitary sensitization in the control of the estrogen-induced gonadotrophin surge. Reprod Sci. 2007, 14, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shea, J.L.; Wong, P.Y.; Chen, Y. Free testosterone: Clinical utility and important analytical aspects of measurement. Adv. Clin. Chem 2014, 63, 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Shiina, H.; Matsumoto, T.; Sato, T.; Igarashi, K.; Miyamoto, J.; Takemasa, S.; Sakari, M.; Takada, I.; Nakamura, T.; Metzger, D.; et al. Premature ovarian failure in androgen receptor-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dickmeis, T. Glucocorticoids and the circadian clock. J. Endocrinol. 2009, 200, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, E.J.; Vendramini, V.; Restelli, A.; Bertolla, R.P.; Kempinas, W.G.; Avellar, M.C. Impact of adrenalectomy and dexamethasone treatment on testicular morphology and sperm parameters in rats: Insights into the adrenal control of male reproduction. Andrology 2014, 2, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whirledge, S.; Cidlowski, J.A. A role for glucocorticoids in stress-impaired reproduction: Beyond the hypothalamus and pituitary. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 4450–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kratz, E.M.; Piwowar, A. Melatonin, advanced oxidation protein products and total antioxidant capacity as seminal parameters of prooxidant-antioxidant balance and their connection with expression of metalloproteinases in context of male fertility. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2017, 68, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Zheng, Y.; Lv, Y.; Li, F.; Su, L.; Qin, Y.; Zeng, W. Melatonin protects the mouse testis against heat-induced damage. Mol. Hum. Reprod 2020, 26, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bejarano, I.; Monllor, F.; Marchena, A.M.; Ortiz, A.; Lozano, G.; Jimenez, M.I.; Gaspar, P.; Garcia, J.F.; Pariente, J.A.; Rodriguez, A.B.; et al. Exogenous melatonin supplementation prevents oxidative stress-evoked DNA damage in human spermatozoa. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, S.; Murias, L.; Fernandez-Plaza, C.; Diaz, I.; Gonzalez, C.; Otero, J.; Diaz, E. Evidence for clock genes circadian rhythms in human full-term placenta. Syst Biol. Reprod Med. 2015, 61, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simonneaux, V.; Bahougne, T.; Angelopoulou, E. Daily rhythms count for female fertility. Best Pract Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 31, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, M.J.; Wu, T.J.; Handa, R.J. Estrogen receptor-beta agonist diarylpropionitrile: Biological activities of r- and s-enantiomers on behavior and hormonal response to stress. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.J.; Hirata, M.; Yamauchi, N.; Hattori, M.A. Up-regulation of per1 expression by estradiol and progesterone in the rat uterus. J. Endocrinol. 2007, 194, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakamura, T.J.; Sellix, M.T.; Menaker, M.; Block, G.D. Estrogen directly modulates circadian rhythms of per2 expression in the uterus. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 295, E1025–E1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, S.; Wang, M.; Ao, X.; Chang, A.K.; Yang, C.; Zhao, F.; Bi, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, L.; Wu, H. Clock is a substrate of sumo and sumoylation of clock upregulates the transcriptional activity of estrogen receptor-alpha. Oncogene 2013, 32, 4883–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvarez, J.D.; Chen, D.; Storer, E.; Sehgal, A. Non-cyclic and developmental stage-specific expression of circadian clock proteins during murine spermatogenesis. Biol. Reprod 2003, 69, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sellix, M.T.; Murphy, Z.C.; Menaker, M. Excess androgen during puberty disrupts circadian organization in female rats. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 1636–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Franks, S. Polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Int J. Obes (Lond.) 2008, 32, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Franks, S. Genetic and environmental origins of obesity relevant to reproduction. Reprod Biomed. Online 2006, 12, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, P.; Jagannathan, L.; Mahaley, R.E.; Subramanian, M.; Gilbreath, E.T.; Mohankumar, P.S.; Mohankumar, S.M. High fat diet affects reproductive functions in female diet-induced obese and dietary resistant rats. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2012, 24, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mereness, A.L.; Murphy, Z.C.; Sellix, M.T. Developmental programming by androgen affects the circadian timing system in female mice. Biol. Reprod 2015, 92, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapolsky, R.M.; Romero, L.M.; Munck, A.U. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev. 2000, 21, 55–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hasenmajer, V.; Sbardella, E.; Sciarra, F.; Minnetti, M.; Isidori, A.M.; Venneri, M.A. The immune system in cushing’s syndrome. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidori, A.M.; Venneri, M.A.; Graziadio, C.; Simeoli, C.; Fiore, D.; Hasenmajer, V.; Sbardella, E.; Gianfrilli, D.; Pozza, C.; Pasqualetti, P.; et al. Effect of once-daily, modified-release hydrocortisone versus standard glucocorticoid therapy on metabolism and innate immunity in patients with adrenal insufficiency (dream): A single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitellius, G.; Trabado, S.; Bouligand, J.; Delemer, B.; Lombes, M. Pathophysiology of glucocorticoid signaling. Ann. Endocrinol. 2018, 79, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, E.; Stephens, S.B.; Chaing, S.; Munaganuru, N.; Kauffman, A.S.; Breen, K.M. Corticosterone blocks ovarian cyclicity and the lh surge via decreased kisspeptin neuron activation in female mice. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 1187–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, E.D.; Geraghty, A.C.; Ubuka, T.; Bentley, G.E.; Kaufer, D. Stress increases putative gonadotropin inhibitory hormone and decreases luteinizing hormone in male rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 11324–11329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bambino, T.H.; Hsueh, A.J. Direct inhibitory effect of glucocorticoids upon testicular luteinizing hormone receptor and steroidogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Endocrinology 1981, 108, 2142–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whirledge, S.; Cidlowski, J.A. Glucocorticoids, stress, and fertility. Minerva Endocrinol. 2010, 35, 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.N.; Li, L.; Hou, G.; Wang, Z.B.; Hou, Y.; Liu, Z.H.; Schatten, H.; Sun, Q.Y. Glucocorticoid exposure affects female fertility by exerting its effect on the uterus but not on the oocyte: Lessons from a hypercortisolism mouse model. Hum. Reprod 2018, 33, 2285–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhen, T.; Grissom, S.; Afshari, C.; Cidlowski, J.A. Dexamethasone blocks the rapid biological effects of 17beta-estradiol in the rat uterus without antagonizing its global genomic actions. Faseb J. 2003, 17, 1849–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dare, J.B.; Arogundade, B.; Awoniyi, O.O.; Adegoke, A.A.; Adekomi, D.A. Dexamethasone as endocrine disruptor; type i and type ii (anti) oestrogenic actions on the ovary and uterus of adult wistar rats (rattus novergicus). JBRA Assist. Reprod 2018, 22, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristic, N.; Nestorovic, N.; Manojlovic-Stojanoski, M.; Trifunovic, S.; Ajdzanovic, V.; Filipovic, B.; Pendovski, L.; Milosevic, V. Adverse effect of dexamethasone on development of the fetal rat ovary. Fundam Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 33, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Chen, L.; Grant, G.R.; Paschos, G.; Song, W.L.; Musiek, E.S.; Lee, V.; McLoughlin, S.C.; Grosser, T.; Cotsarelis, G.; et al. Timing of expression of the core clock gene bmal1 influences its effects on aging and survival. Sci. Transl Med. 2016, 8, 324ra316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fowden, A.L.; Forhead, A.J. Glucocorticoids as regulatory signals during intrauterine development. Exp. Physiol. 2015, 100, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, R.; Gan, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, W. Endocrine-disrupting effects of pesticides through interference with human glucocorticoid receptor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, J.W.F.; Borges, C.D.S.; Missassi, G.; Pacheco, T.L.; De Grava Kempinas, W. Impact of intrauterine exposure to betamethasone on the testes and epididymides of prepubertal rats. Chem Biol. Interact. 2018, 291, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borges, C.D.S.; Pacheco, T.L.; da Silva, K.P.; Fernandes, F.H.; Gregory, M.; Pupo, A.S.; Salvadori, D.M.F.; Cyr, D.G.; Kempinas, W.G. Betamethasone causes intergenerational reproductive impairment in male rats. Reprod Toxicol. 2017, 71, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Gao, L.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, D.; Li, C.; Wang, A.; Jin, Y. Circadian clock and steroidogenic-related gene expression profiles in mouse leydig cells following dexamethasone stimulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 483, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilacqua, A.; Izzo, G.; Emerenziani, G.P.; Baldari, C.; Aversa, A. Lifestyle and fertility: The influence of stress and quality of life on male fertility. Reprod Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milardi, D.; Luca, G.; Grande, G.; Ghezzi, M.; Caretta, N.; Brusco, G.; De Filpo, G.; Marana, R.; Pontecorvi, A.; Calafiore, R.; et al. Prednisone treatment in infertile patients with oligozoospermia and accessory gland inflammatory alterations. Andrology 2017, 5, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bals-Pratsch, M.; Doren, M.; Karbowski, B.; Schneider, H.P.; Nieschlag, E. Cyclic corticosteroid immunosuppression is unsuccessful in the treatment of sperm antibody-related male infertility: A controlled study. Hum. Reprod 1992, 7, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivier, C.; Vale, W. Stimulatory effect of interleukin-1 on adrenocorticotropin secretion in the rat: Is it modulated by prostaglandins? Endocrinology 1991, 129, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.; Capewell, S.; Reynolds, S.P.; Thomas, J.; Ali, N.J.; Read, G.F.; Henley, R.; Riad-Fahmy, D. Testosterone levels during systemic and inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Respir Med. 1994, 88, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Qian, C.; Ding, C.; Meng, Q.; Zou, Q.; Li, H. Fetal liver mesenchymal stem cells restore ovarian function in premature ovarian insufficiency by targeting mt1. Stem Cell Res. Ther 2019, 10, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elokil, A.A.; Bhuiyan, A.A.; Liu, H.Z.; Hussein, M.N.; Ahmed, H.I.; Azmal, S.A.; Yang, L.; Li, S. The capability of l-carnitine-mediated antioxidant on cock during aging: Evidence for the improved semen quality and enhanced testicular expressions of gnrh1, gnrhr, and melatonin receptors mt 1/2. Poult Sci. 2019, 98, 4172–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino, J.; Macedo, M.; Lozano, G.; Ortiz, A.; Rodriguez, C.; Rodriguez, A.B.; Bejarano, I. Impact of melatonin supplementation in women with unexplained infertility undergoing fertility treatment. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nehme, P.A.; Amaral, F.; Lowden, A.; Skene, D.J.; Cipolla-Neto, J.; Moreno, C.R.C. Reduced melatonin synthesis in pregnant night workers: Metabolic implications for offspring. Med. Hypotheses 2019, 132, 109353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.; Barak, S.; Shine, L.; Kahane, A.; Dagan, Y. Exposure by males to light emitted from media devices at night is linked with decline of sperm quality and correlated with sleep quality measures. Chronobiol. Int 2020, 37, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, M.; Tong, J.; Li, W.P.; Chen, Z.J.; Zhang, C. Melatonin concentration in follicular fluid is correlated with antral follicle count (afc) and in vitro fertilization (ivf) outcomes in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology (art) procedures. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2018, 34, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif Khan, H.; Bhatti, S.; Latif Khan, Y.; Abbas, S.; Munir, Z.; Rahman Khan Sherwani, I.A.; Suhail, S.; Hassan, Z.; Aydin, H.H. Cell-free nucleic acids and melatonin levels in human follicular fluid predict embryo quality in patients undergoing in-vitro fertilization treatment. J. Gynecol. Obstet Hum. Reprod 2020, 49, 101624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchi, M.M.; Bruce, J.N. Human pineal physiology and functional significance of melatonin. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2004, 25, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldhauser, F.; Boepple, P.A.; Schemper, M.; Mansfield, M.J.; Crowley, W.F., Jr. Serum melatonin in central precocious puberty is lower than in age-matched prepubertal children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1991, 73, 793–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergiannaki, J.D.; Soldatos, C.R.; Paparrigopoulos, T.J.; Syrengelas, M.; Stefanis, C.N. Low and high melatonin excretors among healthy individuals. J. Pineal Res. 1995, 18, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughlin, G.A.; Loucks, A.B.; Yen, S.S. Marked augmentation of nocturnal melatonin secretion in amenorrheic athletes, but not in cycling athletes: Unaltered by opioidergic or dopaminergic blockade. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1991, 73, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, M.; Pawlikowski, M.; Nowakowska-Jankiewicz, B.; Kolodziej-Maciejewska, H.; Zieleniewski, J.; Cieslak, D.; Leidenberger, F. Circadian variations in plasma melatonin, fsh, lh, and prolactin and testosterone levels in infertile men. J. Pineal Res. 1990, 9, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilorz, V.; Steinlechner, S. Low reproductive success in per1 and per2 mutant mouse females due to accelerated ageing? Reproduction 2008, 135, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, B.; Albrecht, U.; Kaasik, K.; Sage, M.; Lu, W.; Vaishnav, S.; Li, Q.; Sun, Z.S.; Eichele, G.; Bradley, A.; et al. Nonredundant roles of the mper1 and mper2 genes in the mammalian circadian clock. Cell 2001, 105, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yang, P.; Tang, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, H.; He, Y. Loss-of-function mutations with circadian rhythm regulator per1/per2 lead to premature ovarian insufficiencydagger. Biol. Reprod 2019, 100, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaterna, M.H.; King, D.P.; Chang, A.M.; Kornhauser, J.M.; Lowrey, P.L.; McDonald, J.D.; Dove, W.F.; Pinto, L.H.; Turek, F.W.; Takahashi, J.S. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, clock, essential for circadian behavior. Science 1994, 264, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolatshad, H.; Campbell, E.A.; O’Hara, L.; Maywood, E.S.; Hastings, M.H.; Johnson, M.H. Developmental and reproductive performance in circadian mutant mice. Hum. Reprod 2006, 21, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, D.P.; Zhao, Y.; Sangoram, A.M.; Wilsbacher, L.D.; Tanaka, M.; Antoch, M.P.; Steeves, T.D.; Vitaterna, M.H.; Kornhauser, J.M.; Lowrey, P.L.; et al. Positional cloning of the mouse circadian clock gene. Cell 1997, 89, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boden, M.J.; Varcoe, T.J.; Voultsios, A.; Kennaway, D.J. Reproductive biology of female bmal1 null mice. Reproduction 2010, 139, 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Johnson, B.P.; Shen, A.L.; Wallisser, J.A.; Krentz, K.J.; Moran, S.M.; Sullivan, R.; Glover, E.; Parlow, A.F.; Drinkwater, N.R.; et al. Loss of bmal1 in ovarian steroidogenic cells results in implantation failure in female mice. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14295–14300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alvarez, J.D.; Hansen, A.; Ord, T.; Bebas, P.; Chappell, P.E.; Giebultowicz, J.M.; Williams, C.; Moss, S.; Sehgal, A. The circadian clock protein bmal1 is necessary for fertility and proper testosterone production in mice. J. Biol. Rhythms 2008, 23, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kennaway, D.J.; Boden, M.J.; Voultsios, A. Reproductive performance in female clock delta19 mutant mice. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2004, 16, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.H.; Olson, S.L.; Levine, J.E.; Turek, F.W.; Horton, T.H.; Takahashi, J.S. Vasopressin regulation of the proestrous luteinizing hormone surge in wild-type and clock mutant mice. Biol. Reprod 2006, 75, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Sait, S.F. Luteinizing hormone and its dilemma in ovulation induction. J. Hum. Reprod Sci. 2011, 4, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, G.; Ma, G.; Sun, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xiang, A.; Yang, G.; Sun, S. Leptin receptor mediates bmal1 regulation of estrogen synthesis in granulosa cells. Animals 2019, 9, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeAngelis, A.M.; Roy-O’Reilly, M.; Rodriguez, A. Genetic alterations affecting cholesterol metabolism and human fertility. Biol. Reprod 2014, 91, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, K.L.; Drummond, A.E.; Dyson, M.; Wreford, N.G.; Jones, M.E.; Simpson, E.R.; Findlay, J.K. The ovarian phenotype of the aromatase knockout (arko) mouse. J. Steroid Biochem Mol. Biol. 2001, 79, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.E.; Thorburn, A.W.; Britt, K.L.; Hewitt, K.N.; Wreford, N.G.; Proietto, J.; Oz, O.K.; Leury, B.J.; Robertson, K.M.; Yao, S.; et al. Aromatase-deficient (arko) mice have a phenotype of increased adiposity. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. USA 2000, 97, 12735–12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kudo, T.; Kawashima, M.; Tamagawa, T.; Shibata, S. Clock mutation facilitates accumulation of cholesterol in the liver of mice fed a cholesterol and/or cholic acid diet. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 294, E120–E130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, D.; Cermakian, N.; Brancorsini, S.; Parvinen, M.; Sassone-Corsi, P. No circadian rhythms in testis: Period1 expression is clock independent and developmentally regulated in the mouse. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003, 17, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bebas, P.; Goodall, C.P.; Majewska, M.; Neumann, A.; Giebultowicz, J.M.; Chappell, P.E. Circadian clock and output genes are rhythmically expressed in extratesticular ducts and accessory organs of mice. Faseb j 2009, 23, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liang, X.; Cheng, S.; Jiang, X.; He, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Hou, W.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. The noncircadian function of the circadian clock gene in the regulation of male fertility. J. Biol. Rhythms 2013, 28, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Liang, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hou, W.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z. The circadian clock gene regulates acrosin activity of sperm through serine protease inhibitor a3k. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baburski, A.Z.; Sokanovic, S.J.; Bjelic, M.M.; Radovic, S.M.; Andric, S.A.; Kostic, T.S. Circadian rhythm of the leydig cells endocrine function is attenuated during aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2016, 73, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Xiao, S.; Hao, J.; Liao, X.; Li, G. Cry1 deficiency leads to testicular dysfunction and altered expression of genes involved in cell communication, chromatin reorganization, spermatogenesis, and immune response in mouse testis. Mol. Reprod Dev. 2018, 85, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterlin, A.; Kunej, T.; Peterlin, B. The role of circadian rhythm in male reproduction. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2019, 26, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resuehr, H.E.; Resuehr, D.; Olcese, J. Induction of mper1 expression by gnrh in pituitary gonadotrope cells involves egr-1. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2009, 311, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, A.; Zhu, L.; Blum, I.D.; Mai, O.; Leliavski, A.; Fahrenkrug, J.; Oster, H.; Boehm, U.; Storch, K.F. Global but not gonadotrope-specific disruption of bmal1 abolishes the luteinizing hormone surge without affecting ovulation. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 2924–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elks, C.E.; Perry, J.R.; Sulem, P.; Chasman, D.I.; Franceschini, N.; He, C.; Lunetta, K.L.; Visser, J.A.; Byrne, E.M.; Cousminer, D.L.; et al. Thirty new loci for age at menarche identified by a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perry, J.R.; Day, F.; Elks, C.E.; Sulem, P.; Thompson, D.J.; Ferreira, T.; He, C.; Chasman, D.I.; Esko, T.; Thorleifsson, G.; et al. Parent-of-origin-specific allelic associations among 106 genomic loci for age at menarche. Nature 2014, 514, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- de Vries, L.; Kauschansky, A.; Shohat, M.; Phillip, M. Familial central precocious puberty suggests autosomal dominant inheritance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 1794–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehkalampi, K.; Widen, E.; Laine, T.; Palotie, A.; Dunkel, L. Patterns of inheritance of constitutional delay of growth and puberty in families of adolescent girls and boys referred to specialist pediatric care. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Day, F.R.; Thompson, D.J.; Helgason, H.; Chasman, D.I.; Finucane, H.; Sulem, P.; Ruth, K.S.; Whalen, S.; Sarkar, A.K.; Albrecht, E.; et al. Genomic analyses identify hundreds of variants associated with age at menarche and support a role for puberty timing in cancer risk. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn-Evans, E.E.; Stevens, R.G.; Tabandeh, H.; Schernhammer, E.S.; Lockley, S.W. Effect of light perception on menarche in blind women. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2009, 16, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weger, B.D.; Gobet, C.; Yeung, J.; Martin, E.; Jimenez, S.; Betrisey, B.; Foata, F.; Berger, B.; Balvay, A.; Foussier, A.; et al. The mouse microbiome is required for sex-specific diurnal rhythms of gene expression and metabolism. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 362–382.e368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montagner, A.; Korecka, A.; Polizzi, A.; Lippi, Y.; Blum, Y.; Canlet, C.; Tremblay-Franco, M.; Gautier-Stein, A.; Burcelin, R.; Yen, Y.C.; et al. Hepatic circadian clock oscillators and nuclear receptors integrate microbiome-derived signals. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisanti, L.; Olsen, J.; Basso, O.; Thonneau, P.; Karmaus, W. Shift work and subfecundity: A european multicenter study. European study group on infertility and subfecundity. J. Occup Environ. Med. 1996, 38, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labyak, S.; Lava, S.; Turek, F.; Zee, P. Effects of shiftwork on sleep and menstrual function in nurses. Health Care Women Int 2002, 23, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Meng, N.; Bao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, N.; Wu, K.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Kong, S.; Zhang, Y. Circadian gene per1 senses progesterone signal during human endometrial decidualization. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 243, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Wang, N.; Ma, J.; Li, W.P.; Chen, Z.J.; Zhang, C. Impaired decidualization caused by downregulation of circadian clock gene bmal1 contributes to human recurrent miscarriagedagger. Biol. Reprod 2019, 101, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovanen, L.; Saarikoski, S.T.; Aromaa, A.; Lonnqvist, J.; Partonen, T. Arntl (bmal1) and npas2 gene variants contribute to fertility and seasonality. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Xu, Y.; Miao, B.; Zhao, H.; Luo, L.; Shi, H.; Zhou, C. Expression pattern of circadian genes and steroidogenesis-related genes after testosterone stimulation in the human ovary. J. Ovarian Res. 2016, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brzezinski, A.; Saada, A.; Miller, H.; Brzezinski-Sinai, N.A.; Ben-Meir, A. Is the aging human ovary still ticking?: Expression of clock-genes in luteinized granulosa cells of young and older women. J. Ovarian Res. 2018, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Z. Circadian clock gene plays a key role on ovarian cycle and spontaneous abortion. Cell Physiol. Biochem 2015, 37, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, O.; Ding, X.; Nie, J.; Xia, Y.; Wang, X.; Tong, J.; Zhang, J. Variants of the clock gene affect the risk of idiopathic male infertility in the han-chinese population. Chronobiol. Int 2015, 32, 959–965. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, X.; Li, Y.; Xia, Y.; Nie, J.; Yi, C.; Wang, X.; Tong, J. Association of clock gene variants with semen quality in idiopathic infertile han-chinese males. Reprod Biomed. Online 2012, 25, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R.; Bakircioglu, M.E.; Cengiz, C.; Karaca, E.; Scovell, J.; Jhangiani, S.N.; Akdemir, Z.C.; Bainbridge, M.; Yu, Y.; Huff, C.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies novel homozygous mutation in npas2 in family with nonobstructive azoospermia. Fertil Steril 2015, 104, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Hormones | Rhythmicity | Effects on Male | Effects on Female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSH | 24 h circadian rhythm during follicular phase [25] | 24 h circadian rhythm during luteal phase [25] | Sertoli cell tropism and sperm production [20] | Stimulation of estrogens production by ovarian granulosa cells [22] |

| LH | 24 h circadian rhythm during follicular phase [25] | No circadian rhythm in luteal phase [25] | Stimulation of testosterone production by Leydig cells [21] | Stimulation of estrogens production by ovarian granulosa cells [22] |

| Regulation of theca cells androgen production [26] | ||||

| Estrogens | 24 h circadian rhythm during follicular phase [25] | No circadian rhythm in luteal phase [25] | Regulation of ductal and epididymal function [27] | Development and maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics [28] |

| Androgens | 24 h circadian rhythm with a peak in the early morning [26] | Development and maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics [29] | Control of growing follicles [30] | |

| Glucocorticoids | 24 h circadian rhythm with a peak in the morning [31] | Promotion of sperm maturation and steroidogenesis [32] | Regulation of fetal growth and development [33] | |

| Melatonin | 24 h circadian rhythm with a peak in the night [34] | Preservation of spermatogenesis [35,36] | Control of neurological and endocrine systems development [37] | |

| Reduction of free radicals protecting sperm from oxidative damage [35,36] | Protection of the embryo/fetus from metabolic stress [37] | |||

| Disrupted Genes | Effects | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Per1, Per2 | Significant decrease of ovarian follicles in aged mice | [86] |

| Accelerated reproductive aging | [86] | |

| ClockΔ19/Δ19 | Higher rate of pregnancy failure in aged mice | [89] |

| Bmal1 | Delayed puberty | [90] |

| Irregular estrous cycles | [90] | |

| Smaller ovaries and uterus | [90] | |

| Disrupted StAR gene expression | [91] | |

| Lower progesterone levels | [91] |

| Disrupted Genes | Effects | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Clock | Significant fertility reduction | [103] |

| Lower in vitro fertility rate | [103] | |

| Lower blastula formation rate | [103] | |

| Lower acrosin activity | [103] | |

| ClockΔ19/Δ19 | Mild sperm fertility in aged mice | [88] |

| Cry | Increase apoptosis of germ cells | [106] |

| Lower epididimal sperm count | [106] | |

| Bmal1 | Total infertility | [92] |

| Disrupted StAR gene expression | [92] | |

| Leydig cell impairment | [105] |

| Mutated Genes | Effects | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| PER1 | Attenuated human endometrial decidual transformation | [120] |

| BMAL1 | Damaged decidualization | [121] |

| Aberrant trophoblastic invasion | [121] | |

| BMAL1 polymorphism rs2278TT749 | Associated both with a great number of miscarriages but also with an increased number of pregnancies | [122] |

| Mutated Genes | Effects | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| CLOCK polymorphism rs1801260 | Normal seminal parameters | [126] |

| CLOCK polymorphism rs3817444 | Normal and abnormal seminal parameters | [126] |

| CLOCK polymorphism rs1801260 TC genotype | Lower motility compared to the TT genotype | [127] |

| CLOCK polymorphism rs3749474 CC genotype | Seminal volume reduction, lower concentration and sperm motility compared to TT genotype | [127] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sciarra, F.; Franceschini, E.; Campolo, F.; Gianfrilli, D.; Pallotti, F.; Paoli, D.; Isidori, A.M.; Venneri, M.A. Disruption of Circadian Rhythms: A Crucial Factor in the Etiology of Infertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3943. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21113943

Sciarra F, Franceschini E, Campolo F, Gianfrilli D, Pallotti F, Paoli D, Isidori AM, Venneri MA. Disruption of Circadian Rhythms: A Crucial Factor in the Etiology of Infertility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(11):3943. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21113943

Chicago/Turabian StyleSciarra, Francesca, Edoardo Franceschini, Federica Campolo, Daniele Gianfrilli, Francesco Pallotti, Donatella Paoli, Andrea M. Isidori, and Mary Anna Venneri. 2020. "Disruption of Circadian Rhythms: A Crucial Factor in the Etiology of Infertility" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 11: 3943. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21113943

APA StyleSciarra, F., Franceschini, E., Campolo, F., Gianfrilli, D., Pallotti, F., Paoli, D., Isidori, A. M., & Venneri, M. A. (2020). Disruption of Circadian Rhythms: A Crucial Factor in the Etiology of Infertility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(11), 3943. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21113943