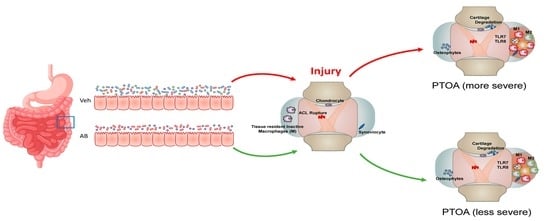

Antibiotic Treatment Prior to Injury Improves Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis Outcomes in Mice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Antibiotic Treatment Prior to Injury Delays Cartilage Resorption in Injured Joints

2.2. Antibiotic Treatment Has a Negative Effect on Bone, Post Injury

2.3. LPS Treatment Compared to AB Treatment

Macrophages Associated with Healing Are Increased in Antibiotic-Treated Joints

2.4. Gene Expression Changes Associated with Chronic Antibiotic Treatment

Comparison of Gene Expression Changes Between Chronic Antibiotic Treatment and LPS Treatment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Tibial Compression Overload

4.2. Micro-Computed Tomography (µCT)

4.3. Histological Assessment of Articular Cartilage and Joint Degeneration

4.4. Immunofluorescent Staining

4.5. RNA Sequencing and Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AB | Antibiotic group |

| ACL | Anterior cruciate ligament |

| BV.TV | Subchondral bone volume |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide group |

| MMP | Metalloproteinase |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| PTOA | Post-traumatic osteoarthritis |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| Tb.N | Trabecular number |

| Tb.Sp | Trabecular spacing |

| Tb.Th | Trabecular thickness |

| TC | Tibial compression |

| μCT | Microcomputed tomography |

| VEH | Vehicle group |

References

- Bull, M.J.; Plummer, N.T. Part 1: The Human Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease. Integr. Med. (Encinitas) 2014, 13, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van den Elsen, L.W.J.; Garssen, J.; Burcelin, R.; Verhasselt, V. Shaping the Gut Microbiota by Breastfeeding: The Gateway to Allergy Prevention? Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Nakayama, J. Development of the gut microbiota in infancy and its impact on health in later life. Allergol. Int. 2017, 66, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente, J.C.; Ursell, L.K.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: An integrative view. Cell 2012, 148, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liang, D.; Leung, R.K.-K.; Guan, W.; Au, W.W. Involvement of gut microbiome in human health and disease: Brief overview, knowledge gaps and research opportunities. Gut Pathog. 2018, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohajeri, M.H.; Brummer, R.J.M.; Rastall, R.A.; Weersma, R.K.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faas, M.; Eggersdorfer, M. The role of the microbiome for human health: From basic science to clinical applications. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McAleer, J.P.; Vella, A.T. Understanding how lipopolysaccharide impacts CD4 T-cell immunity. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 28, 281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Bahar, B.; O’Doherty, J.V.; Vigors, S.; Sweeney, T. Activation of inflammatory immune gene cascades by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the porcine colonic tissue ex-vivo model. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2016, 186, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendez, M.E.; Sebastian, A.; Murugesh, D.K.; Hum, N.R.; McCool, J.L.; Hsia, A.W.; Christiansen, B.A.; Loots, G.G. LPS-induced Inflammation Prior to Injury Exacerbates the Development of Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis in Mice. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.-B.; Pimentel-Nunes, P.; Roncon-Albuquerque, R.; Leite-Moreira, A. The role of lipopolysaccharide/toll-like receptor 4 signaling in chronic liver diseases. Hepatol. Int. 2010, 4, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Calil, I.L.; Zarpelon, A.C.; Guerrero, A.T.G.; Alves-Filho, J.C.; Ferreira, S.H.; Cunha, F.Q.; Cunha, T.M.; Verri, W.A. Lipopolysaccharide induces inflammatory hyperalgesia triggering a TLR4/MyD88-dependent cytokine cascade in the mice paw. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogensen, T.H. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 240–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maslanik, T.; Tannura, K.; Mahaffey, L.; Loughridge, A.B.; Beninson, L.; Benninson, L.; Ursell, L.; Greenwood, B.N.; Knight, R.; Fleshner, M. Commensal bacteria and MAMPs are necessary for stress-induced increases in IL-1β and IL-18 but not IL-6, IL-10 or MCP-1. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Haines, C.J.; Gutcher, I.; Hochweller, K.; Blumenschein, W.M.; McClanahan, T.; Hämmerling, G.; Li, M.O.; Cua, D.J.; McGeachy, M.J. Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells promote T helper 17 cell development in vivo through regulation of interleukin-2. Immunity 2011, 34, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chu, H.; Mazmanian, S.K. Innate immune recognition of the microbiota promotes host-microbial symbiosis. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.H. Host and microbial factors in regulation of T cells in the intestine. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kitaura, H.; Kimura, K.; Ishida, M.; Kohara, H.; Yoshimatsu, M.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Immunological Reaction in TNF-α-Mediated Osteoclast Formation and Bone Resorption In Vitro and In Vivo. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 2013, 181849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCabe, L.R.; Irwin, R.; Schaefer, L.; Britton, R.A. Probiotic use decreases intestinal inflammation and increases bone density in healthy male but not female mice. J. Cell. Physiol. 2013, 228, 1793–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, F.L.; Schepper, J.D.; Rios-Arce, N.D.; Steury, M.D.; Kang, H.J.; Mallin, H.; Schoenherr, D.; Camfield, G.; Chishti, S.; McCabe, L.R.; et al. Immunology of Gut-Bone Signaling. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1033, 59–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teramachi, J.; Inagaki, Y.; Shinohara, H.; Okamura, H.; Yang, D.; Ochiai, K.; Baba, R.; Morimoto, H.; Nagata, T.; Haneji, T. PKR regulates LPS-induced osteoclast formation and bone destruction in vitro and in vivo. Oral. Dis. 2017, 23, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, J.; Yuen, T.; Sun, L.; Zaidi, M. From the gut to the strut: Where inflammation reigns, bone abstains. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 2045–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Charles, J.F.; Ermann, J.; Aliprantis, A.O. The intestinal microbiome and skeletal fitness: Connecting bugs and bones. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 159, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schepper, J.D.; Collins, F.L.; Rios-Arce, N.D.; Raehtz, S.; Schaefer, L.; Gardinier, J.D.; Britton, R.A.; Parameswaran, N.; McCabe, L.R. Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri Prevents Postantibiotic Bone Loss by Reducing Intestinal Dysbiosis and Preventing Barrier Disruption. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2019, 34, 681–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schott, E.M.; Farnsworth, C.W.; Grier, A.; Lillis, J.A.; Soniwala, S.; Dadourian, G.H.; Bell, R.D.; Doolittle, M.L.; Villani, D.A.; Awad, H.; et al. Targeting the gut microbiome to treat the osteoarthritis of obesity. JCI Insight 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guss, J.D.; Ziemian, S.N.; Luna, M.; Sandoval, T.N.; Holyoak, D.T.; Guisado, G.G.; Roubert, S.; Callahan, R.L.; Brito, I.L.; van der Meulen, M.C.H.; et al. The effects of metabolic syndrome, obesity, and the gut microbiome on load-induced osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2019, 27, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulici, V.; Kelley, K.L.; Azcarate-Peril, M.A.; Cleveland, R.J.; Sartor, R.B.; Schwartz, T.A.; Loeser, R.F. Osteoarthritis induced by destabilization of the medial meniscus is reduced in germ-free mice. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2018, 26, 1098–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szychlinska, M.A.; Di Rosa, M.; Castorina, A.; Mobasheri, A.; Musumeci, G. A correlation between intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and osteoarthritis. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hahn, A.K.; Wallace, C.W.; Welhaven, H.D.; Brooks, E.; McAlpine, M.; Christiansen, B.A.; Walk, S.T.; June, R.K. The microbiome mediates subchondral bone loss and metabolomic changes after acute joint trauma. bioRxiv 2020, 2020.05.08.084822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Rodeo, S. Review of current understanding of post-traumatic osteoarthritis resulting from sports injuries. J. Orthop. Res. 2017, 35, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcastle, S.A.; Dieppe, P.; Gregson, C.L.; Davey Smith, G.; Tobias, J.H. Osteoarthritis and bone mineral density: Are strong bones bad for joints? Bonekey Rep. 2015, 4, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Outpatient Antibiotic Prescriptions — United States, 2017; Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017.

- Christiansen, B.A.; Anderson, M.J.; Lee, C.A.; Williams, J.C.; Yik, J.H.N.; Haudenschild, D.R. Musculoskeletal changes following non-invasive knee injury using a novel mouse model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2012, 20, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lockwood, K.A.; Chu, B.T.; Anderson, M.J.; Haudenschild, D.R.; Christiansen, B.A. Comparison of loading rate-dependent injury modes in a murine model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Res. 2014, 32, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, J.C.; Christiansen, B.A.; Murugesh, D.K.; Sebastian, A.; Hum, N.R.; Collette, N.M.; Hatsell, S.; Economides, A.N.; Blanchette, C.D.; Loots, G.G. SOST/Sclerostin Improves Posttraumatic Osteoarthritis and Inhibits MMP2/3 Expression After Injury: SOST OVEREXPRESSION IMPROVES PTOA OUTCOMES. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2018, 33, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sebastian, A.; Chang, J.C.; Mendez, M.E.; Murugesh, D.K.; Hatsell, S.; Economides, A.N.; Christiansen, B.A.; Loots, G.G. Comparative Transcriptomics Identifies Novel Genes and Pathways Involved in Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis Development and Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sebastian, A.; Murugesh, D.K.; Mendez, M.E.; Hum, N.R.; Rios-Arce, N.D.; McCool, J.L.; Christiansen, B.A.; Loots, G.G. Global Gene Expression Analysis Identifies Age-Related Differences in Knee Joint Transcriptome during the Development of Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bouxsein, M.L.; Boyd, S.K.; Christiansen, B.A.; Guldberg, R.E.; Jepsen, K.J.; Müller, R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 1468–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, A.S.; Michalak-Mićka, K.; Biedermann, T.; Simmen-Meuli, C.; Reichmann, E.; Meuli, M. Characterization of M1 and M2 polarization of macrophages in vascularized human dermo-epidermal skin substitutes in vivo. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2018, 34, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairweather, D.; Cihakova, D. Alternatively activated macrophages in infection and autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2009, 33, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wynn, T.A.; Barron, L.; Thompson, R.W.; Madala, S.K.; Wilson, M.S.; Cheever, A.W.; Ramalingam, T. Quantitative Assessment of Macrophage Functions in Repair and Fibrosis. In Current Protocols in Immunology; Coligan, J.E., Bierer, B.E., Margulies, D.H., Shevach, E.M., Strober, W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-471-14273-7. [Google Scholar]

- Culemann, S.; Grüneboom, A.; Nicolás-Ávila, J.Á.; Weidner, D.; Lämmle, K.F.; Rothe, T.; Quintana, J.A.; Kirchner, P.; Krljanac, B.; Eberhardt, M.; et al. Locally renewing resident synovial macrophages provide a protective barrier for the joint. Nature 2019, 572, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Anjos Cassado, A. F4/80 as a Major Macrophage Marker: The Case of the Peritoneum and Spleen. Results Prob. Cell Differ. 2017, 62, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbers, R.; van Schaarenburg, R.A.; Kwekkeboom, J.C.; Levarht, E.W.N.; Bakker, A.M.; Mahdad, R.; Monteagudo, S.; Cherifi, C.; Lories, R.J.; Toes, R.E.M.; et al. Complement component C1q is produced by isolated articular chondrocytes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2020, 28, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarlhelt, I.; Genster, N.; Kirketerp-Møller, N.; Skjoedt, M.-O.; Garred, P. The ficolin response to LPS challenge in mice. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 108, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-C.; Kuo, C.-C.; Chan, C.-H. Association of a BTLA gene polymorphism with the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Biomed. Sci. 2006, 13, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ning, Y.; Guo, X. Integrative meta-analysis of differentially expressed genes in osteoarthritis using microarray technology. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 3439–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smulski, C.R.; Eibel, H. BAFF and BAFF-Receptor in B Cell Selection and Survival. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchelli, C.; Moretti, F.A.; Carmo, M.; Adams, S.; Stanescu, H.C.; Pearce, K.; Madkaikar, M.; Gilmour, K.C.; Nicholas, A.K.; Woods, C.G.; et al. Mutations in linker for activation of T cells (LAT) lead to a novel form of severe combined immunodeficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 634–642.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gotoh, H.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Harigai, M.; Hara, M.; Saito, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Shimada, K.; Kawamoto, M.; Tomatsu, T.; Kamatani, N. Increased CD40 expression on articular chondrocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Contribution to production of cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. J. Rheumatol. 2004, 31, 1506–1512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perdigones, N.; Vigo, A.G.; Lamas, J.R.; Martínez, A.; Balsa, A.; Pascual-Salcedo, D.; de la Concha, E.G.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, B.; Urcelay, E. Evidence of epistasis between TNFRSF14 and TNFRSF6B polymorphisms in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.F.; Kohsaka, H.; Sakurai, H.; Azuma, M.; Okumura, K.; Saito, I.; Miyasaka, N. The presence of costimulatory molecules CD86 and CD28 in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Arthritis Rheum. 1996, 39, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwon, S.-Y.; Rhee, K.-J.; Sung, H.J. Gene and Protein Expression Profiles in a Mouse Model of Collagen-Induced Arthritis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alexopoulos, L.G.; Youn, I.; Bonaldo, P.; Guilak, F. Developmental and osteoarthritic changes in Col6a1-knockout mice: Biomechanics of type VI collagen in the cartilage pericellular matrix. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lv, M.; Zhou, Y.; Polson, S.W.; Wan, L.Q.; Wang, M.; Han, L.; Wang, L.; Lu, X.L. Identification of Chondrocyte Genes and Signaling Pathways in Response to Acute Joint Inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Ni, C.; Xia, L.; Tang, T. SOX11 promotes osteoarthritis through induction of TNF-α. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teufel, S.; Köckemann, P.; König, U.; Hartmann, C. Loss of Wnt9a and Wnt4 causes degenerative joint alterations. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2018, 26, S94–S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Hu, Y.; Song, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yu, F.-X.; Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Izpisua Belmonte, J.C.; Chan, P.; et al. Up-regulation of FOXD1 by YAP alleviates senescence and osteoarthritis. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Fang, X.; Zhao, W.; Liang, Q. The transcriptional coactivator YAP1 is overexpressed in osteoarthritis and promotes its progression by interacting with Beclin-1. Gene 2019, 689, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, N.D.; Vila, O.M.; Volin, M.V.; Volkov, S.; Pope, R.M.; Swedler, W.; Mandelin, A.M.; Shahrara, S. TLR5, a novel and unidentified inflammatory mediator in rheumatoid arthritis that correlates with disease activity score and joint TNF-α levels. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Dang, W.-Q.; Cao, M.-F.; Xiao, J.-F.; Lv, S.-Q.; Jiang, W.-J.; Yao, X.-H.; Lu, H.-M.; Miao, J.-Y.; et al. CCL8 secreted by tumor-associated macrophages promotes invasion and stemness of glioblastoma cells via ERK1/2 signaling. Lab. Investig. 2020, 100, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mödinger, Y.; Rapp, A.; Pazmandi, J.; Vikman, A.; Holzmann, K.; Haffner-Luntzer, M.; Huber-Lang, M.; Ignatius, A. C5aR1 interacts with TLR2 in osteoblasts and stimulates the osteoclast-inducing chemokine CXCL10. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 6002–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; Debnath, B.; Neamati, N. Role of the CXCL8-CXCR1/2 Axis in Cancer and Inflammatory Diseases. Theranostics 2017, 7, 1543–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, S.; Previn, R.; Chen, D.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, G. Role of Forkhead Box O Transcription Factors in Oxidative Stress-Induced Chondrocyte Dysfunction: Possible Therapeutic Target for Osteoarthritis? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yee, C.S.; Manilay, J.O.; Chang, J.C.; Hum, N.R.; Murugesh, D.K.; Bajwa, J.; Mendez, M.E.; Economides, A.E.; Horan, D.J.; Robling, A.G.; et al. Conditional Deletion of Sost in MSC-Derived Lineages Identifies Specific Cell-Type Contributions to Bone Mass and B-Cell Development. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2018, 33, 1748–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, R.; Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Han, L.; Yang, A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, B.; Li, Z.; Xiong, Y. Identification of potential biomarkers for differential diagnosis between rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis via integrative genome-wide gene expression profiling analysis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weiss, A.; Leinwand, L.A. The mammalian myosin heavy chain gene family. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1996, 12, 417–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.C.; Mammucari, C.; Argentini, C.; Reggiani, C.; Schiaffino, S. Two novel/ancient myosins in mammalian skeletal muscles: MYH14/7b and MYH15 are expressed in extraocular muscles and muscle spindles. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2010, 588, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arvanitidis, A.; Henriksen, K.; Karsdal, M.A.; Nedergaard, A. Neo-epitope Peptides as Biomarkers of Disease Progression for Muscular Dystrophies and Other Myopathies. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2016, 3, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chou, C.-H.; Lee, C.-H.; Lu, L.-S.; Song, I.-W.; Chuang, H.-P.; Kuo, S.-Y.; Wu, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.-T.; Kraus, V.B.; Wu, C.-C.; et al. Direct assessment of articular cartilage and underlying subchondral bone reveals a progressive gene expression change in human osteoarthritic knees. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2013, 21, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.H.; Sharma, A.R.; Jagga, S.; Lee, S.S.; Nam, J.S. Differential Expression Patterns of Rspondin Family and Leucine-Rich Repeat-Containing G-Protein Coupled Receptors in Chondrocytes and Osteoblasts. Cell J. 2021, 22, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Arce, N.D.; Schepper, J.D.; Dagenais, A.; Schaefer, L.; Daly-Seiler, C.S.; Gardinier, J.D.; Britton, R.A.; McCabe, L.R.; Parameswaran, N. Post-antibiotic gut dysbiosis-induced trabecular bone loss is dependent on lymphocytes. Bone 2020, 134, 115269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Chen, Z.; Chamberlain, N.D.; Essani, A.B.; Volin, M.V.; Amin, M.A.; Volkov, S.; Gravallese, E.M.; Arami, S.; Swedler, W.; et al. Ligation of TLR5 promotes myeloid cell infiltration and differentiation into mature osteoclasts in rheumatoid arthritis and experimental arthritis. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 3902–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.C.; Sebastian, A.; Murugesh, D.K.; Hatsell, S.; Economides, A.N.; Christiansen, B.A.; Loots, G.G. Global molecular changes in a tibial compression induced ACL rupture model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis: GLOBAL MOLECULAR CHANGES AFTER ACL INJURY. J. Orthop. Res. 2017, 35, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, K.B.S.; Granjeiro, J.M. Bone tissue remodeling and development: Focus on matrix metalloproteinase functions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 561, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatani, T.; Chen, T.; Partridge, N.C. MMP-13 is one of the critical mediators of the effect of HDAC4 deletion on the skeleton. Bone 2016, 90, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klein, T.; Bischoff, R. Physiology and pathophysiology of matrix metalloproteases. Amino Acids 2011, 41, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaushik, D.; Mohan, M.; Borade, D.M.; Swami, O.C. Ampicillin: Rise fall and resurgence. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, ME01–ME03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudobova, D.; Dostalova, S.; Blazkova, I.; Michalek, P.; Ruttkay-Nedecky, B.; Sklenar, M.; Nejdl, L.; Kudr, J.; Gumulec, J.; Tmejova, K.; et al. Effect of ampicillin, streptomycin, penicillin and tetracycline on metal resistant and non-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 3233–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waksman, S.A.; Lechevalier, H.A.; Harris, D.A. Neomycin-production and antibiotic properties. J. Clin. Investig. 1949, 28, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masur, H.; Whelton, P.K.; Whelton, A. Neomycin toxicity revisited. Arch. Surg. 1976, 111, 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, R.H.; Beck, M. Neomycin: A review with particular reference to dermatological usage. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1983, 8, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, B.A.; Guilak, F.; Lockwood, K.A.; Olson, S.A.; Pitsillides, A.A.; Sandell, L.J.; Silva, M.J.; van der Meulen, M.C.H.; Haudenschild, D.R. Non-invasive mouse models of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015, 23, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prys-Roberts, C. Isoflurane. Br. J. Anaesth 1981, 53, 1243–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasson, S.S.; Chambers, M.G.; Van Den Berg, W.B.; Little, C.B. The OARSI histopathology initiative-recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the mouse. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2010, 18 (Suppl. 3), S17–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yee, C.S.; Xie, L.; Hatsell, S.; Hum, N.; Murugesh, D.; Economides, A.N.; Loots, G.G.; Collette, N.M. Sclerostin antibody treatment improves fracture outcomes in a Type I diabetic mouse model. Bone 2016, 82, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Gene | Uninjured | Injured |

|---|---|---|

| Agtr1a | 0.898 | ns |

| Aif1 | 0.740 | ns |

| Btla | 0.880 | ns |

| Ccl4 | 1.437 | ns |

| Ccl6 | 0.679 | ns |

| Ccl7 | −1.600 | ns |

| Ccl8 | −0.790 | ns |

| Ccr3 | 0.998 | ns |

| Ccr6 | 1.522 | ns |

| Ccr7 | 0.931 | ns |

| Ccrl2 | 0.691 | ns |

| Cd40 | 0.829 | ns |

| Cd96 | 1.028 | ns |

| Ciita | 1.033 | ns |

| Clec7a | 0.863 | ns |

| Cntfr | −1.117 | −0.870 |

| Cx3cr1 | 0.856 | ns |

| Cxcl9 | 0.653 | ns |

| Il18 | 0.846 | ns |

| Il1rl1 | 0.685 | 0.696 |

| Il5ra | 0.762 | 0.719 |

| Lat | 0.768 | ns |

| Lat | 0.768 | ns |

| Ms4a1 | 1.293 | ns |

| Pparg | 0.665 | ns |

| Prdx2 | 0.905 | 0.607 |

| Ptgs2 | −0.934 | ns |

| Reg3g | −1.769 | ns |

| Serpine1 | −0.974 | ns |

| Snca | 1.135 | ns |

| Tac2 | 0.789 | ns |

| Tafa3 | −1.234 | −0.905 |

| Tbx21 | ns | −0.913 |

| Tlr5 | −0.987 | ns |

| Tyrobp | 0.645 | ns |

| Gene | Uninjured | Injured |

|---|---|---|

| Bcan | −0.921 | −1.072 |

| Chad | ns | −0.910 |

| Chadl | ns | −0.617 |

| Col18a1 | −0.923 | ns |

| Col1a1 | −0.740 | −0.782 |

| Col2a1 | −0.608 | −0.752 |

| Col3a1 | −0.666 | ns |

| Col5a1 | −0.800 | −0.660 |

| Col6a3 | −1.055 | −0.598 |

| Col7a1 | −0.689 | ns |

| Ddr1 | ns | −0.603 |

| Fzd3 | ns | −0.624 |

| Hapln4 | −0.903 | −0.988 |

| Hoxa11 | ns | −0.696 |

| Hspg2 | −0.805 | −0.660 |

| Matn4 | ns | −0.596 |

| Megf8 | −0.693 | −0.615 |

| Sost | ns | −0.655 |

| Sox10 | ns | −1.405 |

| Sox13 | ns | −0.705 |

| Sox18 | ns | −0.826 |

| Tbx3 | −0.846 | −0.750 |

| Trpv4 | ns | −0.627 |

| Gene | VEH Uninjured | VEH Injured | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB Uninjured | LPS Uninjured | AB Injured | LPS Injured | |

| 4921531C22Rik | 0.680 | 0.945 | ns | ns |

| Aldh3b2 | 1.289 | 0.963 | ns | ns |

| Aldh3b3 | 0.783 | 1.204 | ns | ns |

| Alox15 | 0.652 | 0.674 | ns | ns |

| Arhgef3 | 0.592 | 0.602 | ns | ns |

| Arl11 | 0.652 | 1.176 | ns | ns |

| Ccl4 | 1.437 | 2.782 | ns | ns |

| Ccl6 | 0.679 | 1.222 | ns | ns |

| Cd209a | 1.336 | 0.901 | −0.592 | −0.669 |

| Cd3d | 1.286 | 1.012 | 0.858 | ns |

| Cd84 | 0.673 | 0.776 | ns | ns |

| Cd8b1 | 1.480 | ns | ns | ns |

| Clec7a | 0.863 | 1.204 | ns | ns |

| Csta2 | 1.172 | 1.269 | ns | ns |

| Cstdc4 | 1.338 | 1.411 | ns | ns |

| Cx3cr1 | 0.856 | 1.127 | ns | ns |

| Cyp2ab1 | 1.010 | 1.803 | ns | ns |

| Fgfbp1 | ns | ns | 1.518 | 1.753 |

| Gzma | 1.587 | 1.392 | 0.610 | ns |

| Jaml | 0.638 | 1.826 | ns | ns |

| Klrc2 | 0.784 | 1.324 | ns | ns |

| Lep | −0.701 | −0.682 | ns | ns |

| N4bp2l1 | 0.685 | 0.780 | ns | ns |

| Nat8l | 0.729 | 1.402 | ns | ns |

| Neurl3 | 0.782 | 0.984 | ns | ns |

| P2rx2 | 1.304 | 1.411 | ns | ns |

| Ptpro | 0.780 | 1.169 | ns | ns |

| Rab20 | ns | ns | 0.702 | 0.608 |

| Rspo1 | 0.768 | 1.592 | −0.751 | ns |

| Sirpb1a | 0.803 | 1.056 | ns | ns |

| Sirpb1b | 0.667 | 1.096 | ns | ns |

| Sirpb1c | 0.780 | 1.109 | ns | ns |

| Skint3 | 0.922 | 1.670 | ns | ns |

| Tmem71 | 0.745 | 1.000 | ns | ns |

| Tnnc1 | ns | ns | 0.881 | 0.780 |

| Tyrobp | 0.645 | 0.695 | ns | ns |

| Vnn3 | 0.941 | 1.210 | ns | ns |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mendez, M.E.; Murugesh, D.K.; Sebastian, A.; Hum, N.R.; McCloy, S.A.; Kuhn, E.A.; Christiansen, B.A.; Loots, G.G. Antibiotic Treatment Prior to Injury Improves Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis Outcomes in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176424

Mendez ME, Murugesh DK, Sebastian A, Hum NR, McCloy SA, Kuhn EA, Christiansen BA, Loots GG. Antibiotic Treatment Prior to Injury Improves Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis Outcomes in Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(17):6424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176424

Chicago/Turabian StyleMendez, Melanie E., Deepa K. Murugesh, Aimy Sebastian, Nicholas R. Hum, Summer A. McCloy, Edward A. Kuhn, Blaine A. Christiansen, and Gabriela G. Loots. 2020. "Antibiotic Treatment Prior to Injury Improves Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis Outcomes in Mice" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 17: 6424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176424

APA StyleMendez, M. E., Murugesh, D. K., Sebastian, A., Hum, N. R., McCloy, S. A., Kuhn, E. A., Christiansen, B. A., & Loots, G. G. (2020). Antibiotic Treatment Prior to Injury Improves Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis Outcomes in Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(17), 6424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176424