Phosphoinositide-Dependent Signaling in Cancer: A Focus on Phospholipase C Isozymes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Phospholipases

2.1. Structure and Activation of PLCs Implicated in Cancer

2.1.1. PLCβ

2.1.2. PLCγ

2.1.3. PLCδ

2.1.4. PLCε

3. PLCs in Cancer Development and Progression

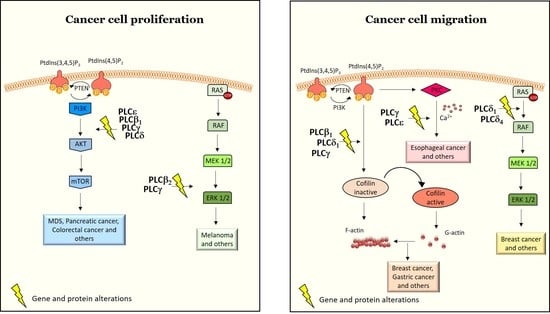

3.1. PLCs in Cancer Cell Proliferation, Survival and Tumor Growth

3.2. PLCs in Cell Migration, Invasiveness and Metastasis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SHIP | Src homology 2 (SH2) domain containing inositol phosphatase |

| 4-Ptase | 4-Phosphatase |

| IPMK | Inositol polyphosphate multikinase |

| PI4-Kinases | Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases |

| PIPK | Phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 |

| OCRL | Oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe |

| INPP | Inositol polyphosphate phosphatase |

| Sac1 | Phosphoinositide phosphatase Sac1 |

| SYNJ | Synaptojanin |

| MTM | Myotubularin |

| MTMRs | Myotubularin-related proteins |

| RAS-GEF | RAS guanine nucleotide exchange factor |

| SH2 | Src homology 2 domain |

| SH3 | Src homology 3 domain |

| spPH | Split PH domain |

| PDZ | Post-synaptic density protein Drosophila disc large tumor suppressor, and zo-1 protein |

| GRB2 | Growth factor receptor-bound protein |

| SOS | Son of sevenless protein |

References

- Van Meer, G.; Voelker, D.R.; Feigenson, G.W. Membrane Lipids: Where They Are and How They Behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.; Bhujwalla, Z.M.; Glunde, K. Targeting Phospholipid Metabolism in Cancer. Target. Phospholipid Metab. Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Glunde, K.; Bhujwalla, Z.M.; Ronen, S.M. Choline Metabolism in Malignant Transformation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hietanen, E.; Punnonen, K.; Punnonen, R.; Auvinen, O. Fatty Acid Composition of Phospholipids and Neutral Lipids and Lipid Peroxidation in Human Breast Cancer and Lipoma Tissue. Carcinogenesis 1986, 7, 1965–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, T. Phosphoinositides: Tiny Lipids with Giant Impact on Cell Regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 1019–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranoff, B.W. Cyclitol Confusion. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1978, 3, 283–285. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, M.N.; Ishiyama, N.; Singaram, I.; Chung, C.M.; Flozak, A.S.; Yemelyanov, A.; Ikura, M.; Cho, W.; Gottardi, C.J. α-Catenin Homodimers Are Recruited to Phosphoinositide-Activated Membranes to Promote Adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 3767–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramos, A.R.; Elong Edimo, W.; Erneux, C. Phosphoinositide 5-Phosphatase Activities Control Cell Motility in Glioblastoma: Two Phosphoinositides PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4)P2 Are Involved. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2018, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemura, S.; Tsuchiya, A.; Kanno, T.; Nakano, T.; Nishizaki, T. Phosphatidylinositol Induces Caspase-Independent Apoptosis of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Cells by Accumulating AIF in the Nucleus. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 36, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, M.G. The Great Escape: How Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinases and PI4P Promote Vesicle Exit from the Golgi (and Drive Cancer). Biochem. J. 2019, 2321–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulicna, L.; Kalendova, A.; Kalasova, I.; Vacik, T.; Hozák, P. PIP2 Epigenetically Represses RRNA Genes Transcription Interacting with PHF8. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2018, 1863, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratti, S.; Follo, M.Y.; Ramazzotti, G.; Faenza, I.; Fiume, R.; Suh, P.G.; McCubrey, J.A.; Manzoli, L.; Cocco, L. Nuclear Phospholipase C Isoenzyme Imbalance Leads to Pathologies in Brain, Hematologic, Neuromuscular, and Fertility Disorders. J. Lipid Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cocco, L.; Follo, M.Y.; Manzoli, L.; Suh, P.G. Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C in Health and Disease. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 1853–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramazzotti, G.; Ratti, S.; Fiume, R.; Follo, M.Y.; Billi, A.M.; Rusciano, I.; Obeng, E.O.; Manzoli, L.; Cocco, L.; Faenza, I. Phosphoinositide 3 Kinase Signaling in Human Stem Cells from Reprogramming to Differentiation: A Tale in Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Compartments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, J.H.; Han, J.S. Phospholipase D and Its Essential Role in Cancer. Mol. Cells 2017, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.F.; Sajinovic, M.; Hein, J.; Nixdorf, S.; Galettis, P.; Liauw, W.; de Souza, P.; Dong, Q.; Graham, G.G.; Russell, P.J. Emerging Roles for Phospholipase A2 Enzymes in Cancer. Biochimie 2010, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, G.A.; Brenot, A.; Haas-Stapleton, E.; Agabian, N.; Deva, R.; Nigam, S. Phospholipase A2 and Phospholipase B Activities in Fungi. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2006, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Follo, M.Y.; Ratti, S.; Manzoli, L.; Ramazzotti, G.; Faenza, I.; Fiume, R.; Mongiorgi, S.; Suh, P.G.; McCubrey, J.A.; Cocco, L. Inositide-Dependent Nuclear Signalling in Health and Disease. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, S.; Mongiorgi, S.; Rusciano, I.; Manzoli, L.; Follo, M.Y. Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 and Phospholipase C-Beta Signalling: Roles and Possible Interactions in Myelodysplastic Syndromes and Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 118649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.B.; Lee, C.S.; Jang, J.H.; Ghim, J.; Kim, Y.J.; You, S.; Hwang, D.; Suh, P.G.; Ryu, S.H. Phospholipase Signalling Networks in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, S.; Mongiorgi, S.; Ramazzotti, G.; Follo, M.Y.; Mariani, G.A.; Suh, P.G.; McCubrey, J.A.; Cocco, L.; Manzoli, L. Nuclear Inositide Signaling Via Phospholipase C. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 1969–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, A.; Billi, A.M.; Mongiorgi, S.; Ratti, S.; Mccubrey, J.A.; Suh, P.-G.; Cocco, L.; Ramazzotti, G. Nuclear Phosphatidylinositol Signaling: Focus on Phosphatidylinositol Phosphate Kinases and Phospholipases C. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 1645–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.G. Regulation of Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001, 70, 281–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faenza, I.; Bavelloni, A.; Fiume, R.; Lattanzi, G.; Maraldi, N.M.; Gilmour, R.S.; Martelli, A.M.; Suh, P.-G.; Billi, A.M.; Cocco, L. Up-Regulation of Nuclear PLCbeta1 in Myogenic Differentiation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003, 195, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, A.M.; Tesmer, J.J.G. Structural Insights into Phospholipase C-β Function. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 84, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martelli, A.M.; Evangelisti, C.; Nyakern, M.; Manzoli, F.A. Nuclear Protein Kinase C. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2006, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatziapostolou, M.; Koukos, G.; Polytarchou, C.; Kottakis, F.; Serebrennikova, O.; Kuliopulos, A.; Tsichlis, P.N. Tumor Progression Locus 2 Mediates Signal-Induced Increases in Cytoplasmic Calcium and Cell Migration. Sci. Signal. 2011, 4, ra55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monteith, G.R.; Prevarskaya, N.; Roberts-Thomson, S.J. The Calcium-Cancer Signalling Nexus. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, C.; Hu, C.D.; Masago, M.; Kariya, K.I.; Yamawaki-Kataoka, Y.; Shibatohge, M.; Wu, D.; Satoh, T.; Kataoka, T. Regulation of a Novel Human Phospholipase C, PLCε, through Membrane Targeting by Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 2752–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart, A.J.; Morgan, K.; Farquharson, C.; Millar, R.P. Phospholipase C-Eta Enzymes as Putative Protein Kinase C and Ca 2+ Signalling Components in Neuronal and Neuroendocrine Tissues. Neuroendocrinology 2007, 86, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manzoli, L.; Billi, A.M.; Gilmour, R.S.; Martelli, A.M.; Matteucci, A.; Rubbini, S.; Weber, G.; Cocco, L. Phosphoinositide Signaling in Nuclei of Friend Cells: Tiazofurin down-Regulates Phospholipase C Beta 1. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 2978–2980. [Google Scholar]

- Cocco, L.; Rubbini, S.; Manzoli, L.; Billi, A.M.; Faenza, I.; Peruzzi, D.; Matteucci, A.; Artico, M.; Gilmour, R.S.; Rhee, S.G. Inositides in the Nucleus: Presence and Characterisation of the Isozymes of Phospholipase Beta Family in NIH 3T3 Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1438, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follo, M.Y.; Faenza, I.; Piazzi, M.; Blalock, W.L.; Manzoli, L.; McCubrey, J.A.; Cocco, L. Nuclear PI-PLCβ1: An Appraisal on Targets and Pathology. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2014, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Cai, M.J.; Zheng, C.C.; Wang, J.X.; Zhao, X.F. Phospholipase Cγ1 Connects the Cell Membrane Pathway to the Nuclear Receptor Pathway in Insect Steroid Hormone Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 13026–13041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stallings, J.D.; Tall, E.G.; Pentyala, S.; Rebecchi, M.J. Nuclear Translocation of Phospholipase C-Δ1 Is Linked to the Cell Cycle and Nuclear Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-Bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 22060–22069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kunrath-Lima, M.; de Miranda, M.C.; da Ferreira, A.F.; Faraco, C.C.F.; de Melo, M.I.A.; Goes, A.M.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Faria, J.A.Q.A.; Gomes, D.A. Phospholipase C Delta 4 (PLCδ4) Is a Nuclear Protein Involved in Cell Proliferation and Senescence in Mesenchymal Stromal Stem Cells. Cell. Signal. 2018, 49, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Malik, S.; Pang, J.; Wang, H.; Park, K.M.; Yule, D.I.; Blaxall, B.C.; Smrcka, A.V. Phospholipase Cε Hydrolyzes Perinuclear Phosphatidylinositol 4-Phosphate to Regulate Cardiac Hypertrophy. Cell 2013, 153, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manzoli, L.; Mongiorgi, S.; Clissa, C.; Finelli, C.; Billi, A.; Poli, A.; Quaranta, M.; Cocco, L.; Follo, M. Strategic Role of Nuclear Inositide Signalling in Myelodysplastic Syndromes Therapy. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongiorgi, S.; Follo, M.Y.; Yang, Y.R.; Manzoli, L.; McCubrey, J.A.; Billi, A.M.; Suh, P.-G.; Cocco, L. Selective Activation of Nuclear PI-PLCbeta1 during Normal and Therapy-Related Differentiation. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illenberger, D.; Walliser, C.; Nürnberg, B.; Lorente, M.D.; Gierschik, P. Specificity and Structural Requirements of Phospholipase C-β Stimulation by Rho GTPases versus G Protein Βγ Dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 3006–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Böhm, D.; Schwegler, H.; Kotthaus, L.; Nayernia, K.; Rickmann, M.; Köhler, M.; Rosenbusch, J.; Engel, W.; Flügge, G.; Burfeind, P. Disruption of PLC-Β1-Mediated Signal Transduction in Mutant Mice Causes Age-Dependent Hippocampal Mossy Fiber Sprouting and Neurodegeneration. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2002, 21, 584–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mende, U.; Kagen, A.; Meister, M.; Neer, E.J. Signal Transduction in Atria and Ventricles of Mice with Transient Cardiac Expression of Activated G Protein α(Q). Circ. Res. 1999, 85, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arthur, J.F.; Matkovich, S.J.; Mitchell, C.J.; Biden, T.J.; Woodcock, E.A. Evidence for Selective Coupling of A1-Adrenergic Receptors to Phospholipase C-Β1 in Rat Neonatal Cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 37341–37346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Suh, P.G.; Park, J.I.; Manzoli, L.; Cocco, L.; Peak, J.C.; Katan, M.; Fukami, K.; Kataoka, T.; Yun, S.; Sung, H.R. Multiple Roles of Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C Isozymes. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Lyubarsky, A.; Dodd, R.; Vardi, N.; Pugh, E.; Baylor, D.; Simon, M.I.; Wu, D. Phospholipase C Β4 Is Involved in Modulating the Visual Response in Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 14598–14601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wells, A.; Grandis, J.R. Phospholipase C-γ 1 in tumor progression. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2003, 20, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, R.; Iezzi, M.; Sala, G.; Tinari, N.; Falasca, M.; Alberti, S.; Buglioni, S.; Mottolese, M.; Perracchio, L.; Natali, P.G.; et al. PLC-Gamma-1 Phosphorylation Status Is Prognostic of Metastatic Risk in Patients with Early-Stage Luminal-A and -B Breast Cancer Subtypes. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, G.; Dituri, F.; Raimondi, C.; Previdi, S.; Maffucci, T.; Mazzoletti, M.; Rossi, C.; Iezzi, M.; Lattanzio, R.; Piantelli, M.; et al. Phospholipase Cγ1 Is Required for Metastasis Development and Progression. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 10187–10196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allen, V.; Swigart, P.; Cheung, R.; Cockcroft, S.; Katan, M. Regulation of Inositol Lipid-Specific Phospholipase Cδ by Changes in Ca2+ Ion Concentrations. Biochem. J. 1997, 327, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagisawa, H.; Okada, M.; Naito, Y.; Sasaki, K.; Yamaga, M.; Fujii, M. Coordinated Intracellular Translocation of Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C-δ with the Cell Cycle. Biochimi. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2006, 1761, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, C.; Jia, W.; Zhu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhong, M.; Xie, D.; et al. PLCD3, a Flotillin2-Interacting Protein, Is Involved in Proliferation, Migration and Invasion of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 39, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shibatohge, M.; Kariya, K.I.; Liao, Y.; Hu, C.D.; Watari, Y.; Goshima, M.; Shima, F.; Kataoka, T. Identification of PLC210, a Caenorhabditis Elegans Phospholipase C, as a Putative Effector of Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 6218–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sorli, S.C.; Bunney, T.D.; Sugden, P.H.; Paterson, H.F.; Katan, M. Signaling Properties and Expression in Normal and Tumor Tissues of Two Phospholipase C Epsilon Splice Variants. Oncogene 2005, 24, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lopez, I.; Mak, E.C.; Ding, J.; Hamm, H.E.; Lomasney, J.W. A Novel Bifunctional Phospholipase C That Is Regulated by Gα 12 and Stimulates the Ras/Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 2758–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wing, M.R.; Snyder, J.T.; Sondek, J.; Harden, T.K. Direct Activation of Phospholipase C-ε by Rho. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 41253–41258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelley, G.G.; Reks, S.E.; Ondrako, J.M.; Smrcka, A.V. Phospholipase Cε: A Novel Ras Effector. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, J.; Owusu Obeng, E.; Ratti, S.; Rusciano, I.; Marvi, M.V.; Fazio, A.; De Stefano, A.; Mongiorgi, S.; Cappellini, A.; Ramazzotti, G.; et al. Nuclear Inositides and Inositide-Dependent Signaling Pathways in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Cells 2020, 9, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mongiorgi, S.; Follo, M.Y.; Clissa, C.; Giardino, R.; Fini, M.; Manzoli, L.; Ramazzotti, G.; Fiume, R.; Finelli, C.; Cocco, L. Nuclear PI-PLC Β1 and Myelodysplastic Syndromes: From Bench to Clinics. In Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 362, pp. 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengelaub, C.A.; Navrazhina, K.; Ross, J.B.; Halberg, N.; Tavazoie, S.F. PTPRN2 and PLCβ1 Promote Metastatic Breast Cancer Cell Migration through PI(4,5)P2-Dependent Actin Remodeling. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Chang, J.T.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Zhu, J.-J. Phospholipase C Beta 1: A Candidate Signature Gene for Proneural Subtype High-Grade Glioma. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 6511–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Follo, M.Y.; Pellagatti, A.; Armstrong, R.N.; Ratti, S.; Mongiorgi, S.; De Fanti, S.; Bochicchio, M.T.; Russo, D.; Gobbi, M.; Miglino, M.; et al. Response of High-Risk MDS to Azacitidine and Lenalidomide Is Impacted by Baseline and Acquired Mutations in a Cluster of Three Inositide-Specific Genes. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2276–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arteaga, C.L.; Johnson, M.D.; Todderud, G.; Coffey, R.J.; Carpenter, G.; Page, D.L. Elevated Content of the Tyrosine Kinase Substrate Phospholipase C-Γ1 in Primary Human Breast Carcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 10435–10439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nomoto, K.; Tomita, N.; Miyake, M.; Xhu, D.B.; LoGerfo, P.R.; Weinstein, I.B. Expression of Phospholipases Gamma 1, Beta 1, and Delta 1 in Primary Human Colon Carcinomas and Colon Carcinoma Cell Lines. Mol. Carcinog 1995, 12, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koss, H.; Bunney, T.D.; Behjati, S.; Katan, M. Dysfunction of Phospholipase Cγ in Immune Disorders and Cancer. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fu, L.; Qin, Y.R.; Xie, D.; Hu, L.; Kwong, D.L.; Srivastava, G.; Sai, W.T.; Guan, X.Y. Characterization of a Novel Tumor-Suppressor Gene PLCδ1 at 3p22 in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 10720–10726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, T.; Ji, J.; Qian, Q.; Lu, L.; Fu, H.; Jin, W.; Cui, D. Differential Expression of Phospholipase C Epsilon 1 Is Associated with Chronic Atrophic Gastritis and Gastric Cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, S.A.; Cekaite, L.; Ågesen, T.H.; Sveen, A.; Nesbakken, A.; Thiis-Evensen, E.; Skotheim, R.I.; Lind, G.E.; Lothe, R.A. Phospholipase C Isozymes Are Deregulated in Colorectal Cancer—Insights Gained from Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of the Transcriptome. PLoS ONE 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bai, Y.; Edamatsu, H.; Maeda, S.; Saito, H.; Suzuki, N.; Satoh, T.; Kataoka, T. Crucial Role of Phospholipase Cε in Chemical Carcinogen-Induced Skin Tumor Development. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 8808–8810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martins, M.; McCarthy, A.; Baxendale, R.; Guichard, S.; Magno, L.; Kessaris, N.; El-Bahrawy, M.; Yu, P.; Katan, M. Tumor Suppressor Role of Phospholipase Ce in Ras-Triggered Cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4239–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shao, Q.; Luo, X.; Yang, D.; Wang, C.; Cheng, Q.; Xiang, T.; Ren, G. Phospholipase Cδ1 Suppresses Cell Migration and Invasion of Breast Cancer Cells by Modulating KIF3A-Mediated ERK1/2/β-Catenin/MMP7 Signalling. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 29056–29066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, X.; Pentassuglia, L.; Sawyer, D.B. Emerging Anticancer Therapeutic Targets and the Cardiovascular System: Is There Cause for Concern? Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 1022–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khoshyomn, S.; Penar, P.L.; Rossi, J.; Wells, A.; Abramson, D.L.; Bhushan, A. Inhibition of Phospholipase C-Γ1 Activation Blocks Glioma Cell Motility and Invasion of Fetal Rat Brain Aggregates. Neurosurgery 1999, 44, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozawa, H.; Howell, G.; Suzuki, S.; Zhang, Q.; Qi, Y.; Klein-Seetharaman, J.; Wells, A.; Grandis, J.R.; Thomas, S.M. Combined Inhibition of PLCγ-1 and c-Src Abrogates Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Mediated Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Invasion. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 4336–4344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Emmanouilidi, A.; Lattanzio, R.; Sala, G.; Piantelli, M.; Falasca, M. The Role of Phospholipase Cγ1 in Breast Cancer and Its Clinical Significance. Future Oncol. 2017, 13, 1991–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramazzotti, G.; Faenza, I.; Fiume, R.; Billi, A.M.; Manzoli, L.; Mongiorgi, S.; Ratti, S.; McCubrey, J.A.; Suh, P.-G.; Cocco, L.; et al. PLC-Β1 and Cell Differentiation: An Insight into Myogenesis and Osteogenesis. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2017, 63, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Fan, Y.; Du, Z.; Fan, J.; Hao, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Luo, C. Knockdown of Phospholipase Cε (PLCε) Inhibits Cell Proliferation via Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog Deleted on Chromosome 10 (PTEN)/AKT Signaling Pathway in Human Prostate Cancer. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Xie, T.; Shui, Y.; Qi, Y. Knockdown of PLCB2 Expression Reduces Melanoma Cell Viability and Promotes Melanoma Cell Apoptosis by Altering Ras/Raf/MAPK Signals. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Hong, H.; Kawakami, Y.; Kato, Y.; Wu, D.; Yasudo, H.; Kimura, A.; Kubagawa, H.; Bertoli, L.F.; Davis, R.S.; et al. Tumor Suppression by Phospholipase C-Β3 via SHP-1-Mediated Dephosphorylation of Stat5. Cancer Cell 2019, 16, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Follo, M.Y.; Manzoli, L.; Poli, A.; McCubrey, J.A.; Cocco, L. PLC and PI3K/Akt/MTOR Signalling in Disease and Cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2015, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmara, M.; Heldin, C.-H.; Lennartsson, J. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-Induced Akt Phosphorylation Requires MTOR/Rictor and Phospholipase C-Γ1, Whereas S6 Phosphorylation Depends on MTOR/Raptor and Phospholipase D. Cell Commun. Signal. 2013, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hua, H.; Kong, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Luo, T.; Jiang, Y. Targeting MTOR for Cancer Therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, V.E.; Nichols, C.; Kim, H.N.; Gang, E.J.; Kim, Y.M. Targeting PI3K Signaling in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramazzotti, G.; Faenza, I.; Follo, M.Y.; Fiume, R.; Piazzi, M.; Giardino, R.; Fini, M.; Cocco, L. Nuclear Phospholipase C in Biological Control and Cancer. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2011, 21, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Follo, M.Y.; Finelli, C.; Bosi, C.; Martinelli, G.; Mongiorgi, S.; Baccarani, M.; Manzoli, L.; Blalock, W.L.; Martelli, A.M.; Cocco, L. PI-PLCβ-1 and Activated Akt Levels Are Linked to Azacitidine Responsiveness in High-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Leukemia. 2008, 22, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Follo, M.Y.; Pellagatti, A.; Ratti, S.; Ramazzotti, G.; Faenza, I.; Fiume, R.; Mongiorgi, S.; Suh, P.G.; McCubrey, J.A.; Manzoli, L.; et al. Recent Advances in MDS Mutation Landscape: Splicing and Signalling. In Advances in Biological Regulation; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; p. 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.L.; Deeg, H.J. Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Annu. Rev. Med. 2010, 61, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, P.L.; Attar, E.; Battiwalla, M.; Bennett, J.M.; Bloomfield, C.D.; DeCastro, C.M.; Deeg, J.; Erba, H.P.; Foran, J.M.; Garcia-Manero, G.; et al. Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Jnccn J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2008, 902–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poli, A.; Ratti, S.; Finelli, C.; Mongiorgi, S.; Clissa, C.; Lonetti, A.; Cappellini, A.; Catozzi, A.; Barraco, M.; Suh, P.G.; et al. Nuclear Translocation of PKC-α Is Associated with Cell Cycle Arrest and Erythroid Differentiation in Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDSs). FASEB J. 2018, 32, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Follo, M.Y.; Finelli, C.; Clissa, C.; Mongiorgi, S.; Bosi, C.; Martinelli, G.; Baccarani, M.; Manzoli, L.; Martelli, A.M.; Cocco, L. Phosphoinositide-Phospholipase C Beta1 Mono-Allelic Deletion Is Associated with Myelodysplastic Syndromes Evolution into Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filì, C.; Malagola, M.; Follo, M.Y.; Finelli, C.; Iacobucci, I.; Martinelli, G.; Cattina, F.; Clissa, C.; Candoni, A.; Fanin, R.; et al. Prospective Phase II Study on 5-Days Azacitidine for Treatment of Symptomatic and/or Erythropoietin Unresponsive Patients with Low/INT-1-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 3297–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramazzotti, G.; Fiume, R.; Chiarini, F.; Campana, G.; Ratti, S.; Billi, A.M.; Manzoli, L.; Follo, M.Y.; Suh, P.-G.; McCubrey, J.; et al. Phospholipase C-Β1 Interacts with Cyclin E in Adipose- Derived Stem Cells Osteogenic Differentiation. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2018, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, S.; Ramazzotti, G.; Faenza, I.; Fiume, R.; Mongiorgi, S.; Billi, A.M.; McCubrey, J.A.; Suh, P.-G.; Manzoli, L.; Follo, M.Y. Nuclear Inositide Signaling and Cell Cycle. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2018, 67, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engebraaten, O.; Bjerkvig, R.; Pedersen, P.-H.; Laerum, O.D. Effects of EGF, BFGF, NGF and PDGF(Bb) on Cell Proliferative, Migratory and Invasive Capacities of Human Brain-Tumour BiopsiesIn Vitro. Int. J. Cancer 1993, 53, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falasca, M.; Logan, S.K.; Lehto, V.P.; Baccante, G.; Lemmon, M.A.; Schlessinger, J. Activation of Phospholipase Cγ by PI 3-Kinase-Induced PH Domain-Mediated Membrane Targeting. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondi, C.; Chikh, A.; Wheeler, A.P.; Maffucci, T.; Falasca, M. A Novel Regulatory Mechanism Links PLCγ1 to PDK1. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 3153–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bertagnolo, V.; Benedusi, M.; Brugnoli, F.; Lanuti, P.; Marchisio, M.; Querzoli, P.; Capitani, S. Phospholipase C-Β2 Promotes Mitosis and Migration of Human Breast Cancer-Derived Cells. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 1638–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Braicu, C.; Buse, M.; Busuioc, C.; Drula, R.; Gulei, D.; Raduly, L.; Rusu, A.; Irimie, A.; Atanasov, A.G.; Slaby, O.; et al. A Comprehensive Review on MAPK: A Promising Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burotto, M.; Chiou, V.L.; Lee, J.M.; Kohn, E.C. The MAPK Pathway across Different Malignancies: A New Perspective. Cancer 2014, 3446–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rong, R.; Ahn, J.Y.; Chen, P.; Suh, P.G.; Ye, K. Phospholipase Activity of Phospholipase C-Γ1 Is Required for Nerve Growth Factor-Regulated MAP Kinase Signaling Cascade in PC12 Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 52497–52503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buckley, C.T.; Sekiya, F.; Yeun, J.K.; Sue, G.R.; Caldwell, K.K. Identification of Phospholipase C-Γ1 as a Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 41807–41814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, X.; Sedwick, D.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Cross-Talk between Phospho-STAT3 and PLCγ1 Plays a Critical Role in Colorectal Tumorigenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2011, 9, 1418–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiume, R.; Faenza, I.; Sheth, B.; Poli, A.; Vidalle, M.C.; Mazzetti, C.; Abdul, S.H.; Campagnoli, F.; Fabbrini, M.; Kimber, S.T.; et al. Nuclear Phosphoinositides: Their Regulation and Roles in Nuclear Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Audhya, A.; Emr, S.D. Regulation of PI4,5P2 Synthesis by Nuclear-Cytoplasmic Shuttling of the Mss4 Lipid Kinase. Embo J. 2003, 22, 4223–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stevenson, R.P.; Veltman, D.; Machesky, L.M. Actin-Bundling Proteins in Cancer Progression at a Glance. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, P.; Murphy-Ullrich, J.E.; Wells, A. A Role for Gelsolin in Actuating Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor- Mediated Cell Motility. J. Cell Biol. 1996, 134, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katterle, Y.; Brandt, B.H.; Dowdy, S.F.; Niggemann, B.; Zänker, K.S.; Dittmar, T. Antitumour Effects of PLC-Γ1-(SH2)2-TAT Fusion Proteins on EGFR/c-ErbB-2-Positive Breast Cancer Cells. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 90, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, X.T.; Zhang, F.B.; Fan, Y.C.; Shu, X.S.; Wong, A.H.Y.; Zhou, W.; Shi, Q.L.; Tang, H.M.; Fu, L.; Guan, X.Y.; et al. Phospholipase c Delta 1 Is a Novel 3p22.3 Tumor Suppressor Involved in Cytoskeleton Organization, with Its Epigenetic Silencing Correlated with High-Stage Gastric Cancer. Oncogene 2009, 28, 2466–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Villalobo, A.; Berchtold, M.W. The Role of Calmodulin in Tumor Cell Migration, Invasiveness, and Metastasis. Int, J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shepard, C.R.; Kassis, J.; Whaley, D.L.; Kim, H.G.; Wells, A. PLCγ Contributes to Metastasis of in Situ-Occurring Mammary and Prostate Tumors. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3020–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomas, S.M.; Coppelli, F.M.; Wells, A.; Gooding, W.E.; Song, J.; Kassis, J.; Drenning, S.D.; Grandis, J.R. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Stimulated Activation of Phospholipase Cγ-1 Promotes Invasion of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 5629–5635. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.; Zhou, J.; Fu, J.; He, T.; Qin, J.; Wang, L.; Liao, L.; Xu, J. Phosphorylation of Serine 68 of Twist1 by MAPKs Stabilizes Twist1 Protein and Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Invasiveness. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 3980–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, J.; Fan, Y.; Wang, X.; Niu, L.; Duan, L.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Wu, X.; Luo, C. PLCϵ Regulates Prostate Cancer Mitochondrial Oxidative Metabolism and Migration via Upregulation of Twist1. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Luan, C. PLCE1 Promotes the Invasion and Migration of Esophageal Cancer Cells by Up-Regulating the PKCα/NF-ΚB Pathway. Yonsei Med. J. 2018, 59, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Warren, S.; Kimberley, C.; Margineanu, A.; Peschard, P.; Mccarthy, A.; Yeo, M.; Marshall, C.J.; Dunsby, C.; French, P.M.W.; et al. Activity of PLCe Contributes to Chemotaxis of Fibroblasts towards PDGF. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 5758–5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leung, D.W.; Tompkins, C.; Brewer, J.; Ball, A.; Coon, M.; Morris, V.; Waggoner, D.; Singer, J.W. Phospholipase C Delta-4 Overexpression Upregulates ErB1/2 Expression, Erk Signaling Pathway, and Proliferation in MCF-7 Cells. Mol. Cancer 2004, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tanimura, S.; Takeda, K. ERK Signalling as a Regulator of Cell Motility. J. Biochem. 2017, 162, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| PLC Isoforms | Tumor Entity | Tumor Specificity | Mode of Experimentation | Pathways Altered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLCβ1 | MDS | Diseased patients | Expression profiling | Akt/mTOR |

| PLCβ2 | Melanoma | Melanoma cells | Functional studies | RAS/RAF/MAPK |

| PLCβ3 | Lymphoma | Mutant mice | Functional studies | JAK/STAT |

| PLCβ3 | Breast cancer | MDA-MB231 cells | Functional studies | MEK/ERK |

| PLCγ | Pheochromocytoma | PC12 cells | Functional studies | PI3K/Akt/mTOR and RAF/MEK/MAPK |

| Colorectal cancer | Functional studies | JAK/STAT | ||

| PLCδ1 | ESCC | ESCC cell lines | Functional studies | PI3K/Akt |

| Breast Cancer | Diseased cell lines | Functional studies | ERK1/2/β-catenin/MMP | |

| PLCε | Pancreatic cancer | Diseased cell lines | Functional studies | PTEN/Akt |

| Prostate cancer | Diseased cell lines | Functional studies | RAS/RAF/MAPK |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Owusu Obeng, E.; Rusciano, I.; Marvi, M.V.; Fazio, A.; Ratti, S.; Follo, M.Y.; Xian, J.; Manzoli, L.; Billi, A.M.; Mongiorgi, S.; et al. Phosphoinositide-Dependent Signaling in Cancer: A Focus on Phospholipase C Isozymes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21072581

Owusu Obeng E, Rusciano I, Marvi MV, Fazio A, Ratti S, Follo MY, Xian J, Manzoli L, Billi AM, Mongiorgi S, et al. Phosphoinositide-Dependent Signaling in Cancer: A Focus on Phospholipase C Isozymes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(7):2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21072581

Chicago/Turabian StyleOwusu Obeng, Eric, Isabella Rusciano, Maria Vittoria Marvi, Antonietta Fazio, Stefano Ratti, Matilde Yung Follo, Jie Xian, Lucia Manzoli, Anna Maria Billi, Sara Mongiorgi, and et al. 2020. "Phosphoinositide-Dependent Signaling in Cancer: A Focus on Phospholipase C Isozymes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 7: 2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21072581

APA StyleOwusu Obeng, E., Rusciano, I., Marvi, M. V., Fazio, A., Ratti, S., Follo, M. Y., Xian, J., Manzoli, L., Billi, A. M., Mongiorgi, S., Ramazzotti, G., & Cocco, L. (2020). Phosphoinositide-Dependent Signaling in Cancer: A Focus on Phospholipase C Isozymes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(7), 2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21072581