Comparison of the Feasibility, Efficiency, and Safety of Genome Editing Technologies

Abstract

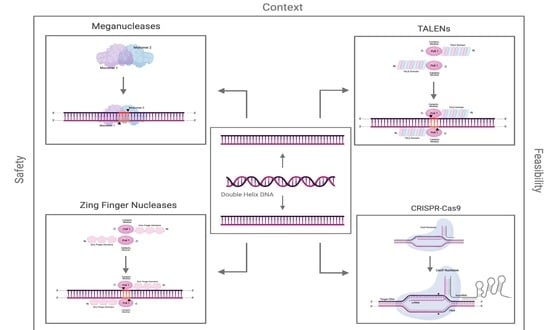

:1. Introduction

Double-Strand Breaks and Repair Mechanisms

2. Meganucleases

2.1. Origin, Structure, and Function

2.2. Feasibility

2.3. Efficiency

2.4. Safety

3. Zinc Finger Nucleases

3.1. Origin, Structure, and Function

3.2. Feasibility

3.3. Efficiency

3.4. Safety

4. TALENs

4.1. Origin, Structure, and Function

4.2. Feasibility

4.3. Efficiency

4.4. Safety

5. CRISPR-Cas

5.1. Origin, Structure, and Function

5.2. Feasibility

5.3. Delivery Methods

5.4. Efficiency

5.5. Safety

6. Conclusions

6.1. Focus and Expectations Are on CRISPR-Cas, but Do Not Discount the Other Platforms

6.2. If CRISPR-Cas Is to Be Used, Consider High-Fidelity Variants of SpCas9

6.3. Despite Its Versatility, CRISPR-Cas Also Faces Limitations of Its Own

6.4. When Deciding on Which Genome Editing Platform to Use, Assess All the Features Related to Safety, Not Only Off-Target Activity

6.5. Independently Validate Parameters of the Selected Platform Prior to Commitment

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| TALEN | Transcription activator-like effector nuclease |

| CRISPR-Cas | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-Cas |

| DSB | Double-strand break |

| NHEJ | Nonhomologous end joining |

| HDR | Homology-directed repair |

| Indel | Nucleotide insertion and deletion |

| MN | Meganuclease |

| HE | Homing endonuclease |

| bp | Base pair |

| IVC | In vitro compartmentalised system |

| MT | MegaTAL |

| TALE | Transcription activator-like effector |

| RDEB | Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa |

| TCRα | T cell receptor alpha |

| RDEB-K | Primary recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa keratinocyte |

| RDEB-F | Primary recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa fibroblast |

| IDLV | Integrase-deficient lentiviral vector |

| SCID | Severe combined immunodeficiency |

| XPC | Xeroderma pigmentosum group C |

| DMD | Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

| ZFN | Zinc finger nuclease |

| ZF | Zinc finger |

| C2H2 | Cys2/His2 |

| OPEN | Oligomerised pool engineering |

| CoDA | Context-dependent assembly |

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus |

| LV | Lentiviral vector |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HSPC | Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell |

| iPSC | Induced pluripotent stem cell |

| RVD | Repeat variable diresidue |

| RVR | Repeat variable residue |

| SCD | Sickle cell disease |

| hiPSC | Human induced pluripotent stem cells |

| AAT | Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency |

| AAVS1 | Adeno-associated virus integration site 1 |

| NuFF | Newborn foreskin fibroblast |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| bRosa26-EGFP | Bovine rosa26-enhanced green fluorescent protein |

| RMCE | Recombinase-mediated cassette exchange |

| HTGTS | High-throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing |

| Cas | CRISPR-associated protein |

| crRNA | CRISPR RNA |

| PAM | Protospacer adjacent motif |

| tracrRNA | Trans-activating CRISPR RNA |

| sgRNA | Single guide RNA |

| dsDNA | Double-stranded DNA |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| 2′OMe | 2′-O-methyl |

| 2′MOE | 2′-O-methoxyethyl |

| 2′F | 2′-fluoro |

| 3′PS | 3′-phosphorothioate |

| 3′thioPACE | 3′thiophosphonoacetate linkage |

| nCas9 | Cas9 nickase |

| dCas9 | Dead Cas9 |

| HTS | High-throughput sequencing |

| RNP | Ribonucleoprotein |

| T7E1 | T7 endonuclease I |

| FAST | Far-red light-activated split-Cas9 system |

| gRNA | Guide RNA |

| RFN | RNA-guided FokI–dCas9 nuclease |

| Cas9-pDBD | Programmable DNA-binding domain |

| hPSC | Human pluripotent stem cell |

References

- Lieber, M.R. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010, 79, 181–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jasin, M.; Rothstein, R. Repair of strand breaks by homologous recombination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a012740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, V.; Hergovich, A. Cell-cycle control and DNA-damage signaling in mammals. In Genome Stability; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 227–242. ISBN 978-0-12-803309-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ghezraoui, H.; Piganeau, M.; Renouf, B.; Renaud, J.-B.; Sallmyr, A.; Ruis, B.; Oh, S.; Tomkinson, A.E.; Hendrickson, E.A.; Giovannangeli, C.; et al. Chromosomal translocations in human cells are generated by canonical nonhomologous end-joining. Mol. Cell 2014, 55, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lambert, A.R.; Hallinan, J.P.; Shen, B.W.; Chik, J.K.; Bolduc, J.M.; Kulshina, N.; Robins, L.I.; Kaiser, B.K.; Jarjour, J.; Havens, K.; et al. Indirect DNA sequence recognition and its impact on nuclease cleavage activity. Structure 2016, 24, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Takeuchi, R.; Choi, M.; Stoddard, B.L. Redesign of extensive protein-DNA interfaces of meganucleases using iterative cycles of in vitro compartmentalization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4061–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porter, S.N.; Levine, R.M.; Pruett-Miller, S.M. A practical guide to genome editing using targeted nuclease technologies. Compr. Physiol. 2019, 9, 665–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcaida, M.J.; Muñoz, I.G.; Blanco, F.J.; Prieto, J.; Montoya, G. Homing endonucleases: From basics to therapeutic applications. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, R.; Montoya, G.; Prieto, J. Meganucleases and Their Biomedical Applications. In eLS; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2011; p. a0023179. ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6. [Google Scholar]

- Belfort, M.; Bonocora, R.P. Homing endonucleases: From genetic anomalies to programmable genomic clippers. Homing Endonucleases 2014, 1123, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pâques, F.; Duchateau, P. Meganucleases and DNA double-strand break-induced recombination: Perspectives for gene therapy. Gene 2007, 7, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.; Poirot, L.; Galetto, R.; Smith, J.; Montoya, G.; Duchateau, P.; Pâques, F. Meganucleases and other tools for targeted genome engineering: Perspectives and challenges for gene therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2011, 11, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stoddard, B.L. Homing endonucleases from mobile group i introns: Discovery to genome engineering. Mob. DNA 2014, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.H. Genome editing technologies: Concept, pros and cons of various genome editing techniques and bioethical concerns for clinical application. Mol. Ther.-Nucleic Acids 2019, 16, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Galetto, R.; Duchateau, P.; Pâques, F. Targeted approaches for gene therapy and the emergence of engineered meganucleases. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2009, 9, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochtler, M. Indirect DNA sequence readout by LAGLIDADG homing endonucleases. Structure 2016, 24, 839–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guha, T.; Edgell, D. Applications of alternative nucleases in the age of CRISPR/Cas9. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambert, A.R.; Hallinan, J.P.; Werther, R.; Głów, D.; Stoddard, B.L. Optimization of protein thermostability and exploitation of recognition behavior to engineer altered protein-DNA recognition. Structure 2020, 28, 760–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissel, S.; Jarjour, J.; Astrakhan, A.; Adey, A.; Gouble, A.; Duchateau, P.; Shendure, J.; Stoddard, B.L.; Certo, M.T.; Baker, D.; et al. MegaTALs: A rare-cleaving nuclease architecture for therapeutic genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 42, 2591–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, M.J.; Webber, B.R.; Knipping, F.; Lonetree, C.; Tennis, N.; DeFeo, A.P.; McElroy, A.N.; Starker, C.G.; Lee, C.; Merkel, S.; et al. Evaluation of TCR gene editing achieved by TALENs, CRISPR/Cas9, and megaTAL nucleases. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Izmiryan, A.; Danos, O.; Hovnanian, A. Meganuclease-mediated COL7A1 gene correction for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 872–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Grizot, S.; Arnould, S.; Duclert, A.; Epinat, J.-C.; Chames, P.; Prieto, J.; Redondo, P.; Blanco, F.J.; Bravo, J.; et al. A combinatorial approach to create artificial homing endonucleases cleaving chosen sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grizot, S.; Smith, J.; Daboussi, F.; Prieto, J.; Redondo, P.; Merino, N.; Villate, M.; Thomas, S.; Lemaire, L.; Montoya, G.; et al. Efficient targeting of a SCID gene by an engineered single-chain homing endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 5405–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tolarová, M.; McGrath, J.A.; Tolar, J. Venturing into the new science of nucleases. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 742–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muñoz, I.G.; Prieto, J.; Subramanian, S.; Coloma, J.; Redondo, P.; Villate, M.; Merino, N.; Marenchino, M.; D’Abramo, M.; Gervasio, F.L.; et al. Molecular basis of engineered meganuclease targeting of the endogenous human RAG1 locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Redondo, P.; Prieto, J.; Muñoz, I.G.; Alibés, A.; Stricher, F.; Serrano, L.; Cabaniols, J.-P.; Daboussi, F.; Arnould, S.; Perez, C.; et al. Molecular basis of xeroderma pigmentosum group C DNA recognition by engineered meganucleases. Nature 2008, 456, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapdelaine, P.; Pichavant, C.; Rousseau, J.; Pâques, F.; Tremblay, J.P. Meganucleases can restore the reading frame of a mutated dystrophin. Gene Ther. 2010, 17, 846–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Renfer, E.; Technau, U. Meganuclease-assisted generation of stable transgenics in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 1844–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Hong, W.; Huang, M.; Wu, M.; Zhao, X. Applications of genome editing technology in the targeted therapy of human diseases: Mechanisms, advances and prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevisan, M.; Palù, G.; Barzon, L. Genome editing technologies to fight infectious diseases. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2017, 15, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cathomen, T.; Joung, J.K. Zinc-finger nucleases: The next generation emerges. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.-T.; Leng, Q.; Mixson, J. Zinc finger nucleases: Tailor-made for gene therapy. Drugs Future 2012, 37, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Handel, E.-M.; Cathomen, T. Zinc-finger nuclease based genome surgery: Its all about specificity. Curr. Gene Ther. 2011, 11, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, D.; Morton, J.J.; Beumer, K.J.; Segal, D.J. Design, construction and in vitro testing of zinc finger nucleases. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 1329–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.; Cho, S.W.; Kim, J.-S. Targeted genome editing in human cells with zinc finger nucleases constructed via modular assembly. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Petersen, B.; Niemann, H. Advances in genetic modification of farm animals using zinc-finger nucleases (ZFN). Chromosome Res. 2015, 23, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasegaran, S. Recent advances in the use of ZFN-mediated gene editing for human gene therapy. Cell Gene Ther. Insights 2017, 3, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabalameli, H.R.; Zahednasab, H.; Karimi-Moghaddam, A.; Jabalameli, M.R. Zinc finger nuclease technology: Advances and obstacles in modelling and treating genetic disorders. Gene 2015, 558, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, Y.; Şöllü, C.; Meckler, J.F.; Adriaenssens, A.; Zykovich, A.; Cathomen, T.; Segal, D.J. Adding fingers to an engineered zinc finger nuclease can reduce activity. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 5033–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mussolino, C.; Cathomen, T. TALE nucleases: Tailored genome engineering made easy. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mussolino, C.; Alzubi, J.; Fine, E.J.; Morbitzer, R.; Cradick, T.J.; Lahaye, T.; Bao, G.; Cathomen, T. TALENs facilitate targeted genome editing in human cells with high specificity and low cytotoxicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 6762–6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greisman, H.A.; Pabo, C.O. A general strategy for selecting high-affinity zinc finger proteins for diverse DNA target sites. Science 1997, 275, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isalan, M.; Klug, A.; Choo, Y. A rapid, generally applicable method to engineer zinc fingers illustrated by targeting the HIV-1 promoter. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Carter, S.; Fink, K. Design, construction, and application of transcription activation-like effectors. In Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy: Methods and Protocols; Manfredsson, F.P., Benskey, M.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 47–58. ISBN 978-1-4939-9065-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ousterout, D.G.; Gersbach, C.A. The development of TALE nucleases for biotechnology. In TALENs; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1338, pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paschon, D.E.; Lussier, S.; Wangzor, T.; Xia, D.F.; Li, P.W.; Hinkley, S.J.; Scarlott, N.A.; Lam, S.C.; Waite, A.J.; Truong, L.N.; et al. Diversifying the structure of zinc finger nucleases for high-precision genome editing. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carroll, D. Genome engineering with zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics 2011, 188, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, J.C.; Patil, D.P.; Xia, D.F.; Paine, C.B.; Fauser, F.; Richards, H.W.; Shivak, D.A.; Bendaña, Y.R.; Hinkley, S.J.; Scarlott, N.A.; et al. Enhancing gene editing specificity by attenuating DNA cleavage kinetics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urnov, F.D.; Miller, J.C.; Lee, Y.-L.; Beausejour, C.M.; Rock, J.M.; Augustus, S.; Jamieson, A.C.; Porteus, M.H.; Gregory, P.D.; Holmes, M.C. Highly efficient endogenous human gene correction using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nature 2005, 435, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornu, T.I.; Thibodeau-Beganny, S.; Guhl, E.; Alwin, S.; Eichtinger, M.; Joung, J.; Cathomen, T. DNA-Binding specificity is a major determinant of the activity and toxicity of zinc-finger nucleases. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.; Wang, J.; Kim, K.; Friedman, G.; Wang, X.; Taupin, V.; Crooks, G.M.; Kohn, D.B.; Gregory, P.D.; Holmes, M.C.; et al. Human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells modified by zinc-finger nucleases targeted to CCR5 control HIV-1 in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perez, E.E.; Wang, J.; Miller, J.C.; Jouvenot, Y.; Kim, K.A.; Liu, O.; Wang, N.; Lee, G.; Bartsevich, V.V.; Lee, Y.-L.; et al. Establishment of HIV-1 resistance in CD4+ T cells by genome editing using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sebastiano, V.; Maeder, M.L.; Angstman, J.F.; Haddad, B.; Khayter, C.; Yeo, D.T.; Goodwin, M.J.; Hawkins, J.S.; Ramirez, C.L.; Batista, L.F.Z.; et al. In situ genetic correction of the sickle cell anemia mutation in human induced pluripotent stem cells using engineered zinc finger nucleases. Stem Cells 2011, 29, 1717–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pattanayak, V.; Ramirez, C.L.; Joung, J.K.; Liu, D.R. Revealing off-target cleavage specificities of zinc-finger nucleases by in vitro selection. Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yee, J. Off-target effects of engineered nucleases. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 3239–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, S.; Kandavelou, K.; Rajenderan, R.; Chandrasegaran, S. Creating designed zinc-finger nucleases with minimal cytotoxicity. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 405, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richter, A.; Streubel, J.; Boch, J. TAL effector DNA-binding principles and specificity. In TALENs; Kühn, R., Wurst, W., Wefers, B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1338, pp. 9–25. ISBN 978-1-4939-2931-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mariano, A.; Xu, L.; Han, R. Highly efficient genome editing via 2A-coupled co-expression of two TALEN monomers. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, J. Generate TALE/TALEN as easily and rapidly as generating CRISPR. Mol. Ther.-Methods Clin. Dev. 2019, 13, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mussolino, C.; Morbitzer, R.; Lütge, F.; Dannemann, N.; Lahaye, T.; Cathomen, T. A novel TALE nuclease scaffold enables high genome editing activity in combination with low toxicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 9283–9293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Fernández, J.M.; Fleischer, A.; Vallejo-Diez, S.; Palomino, E.; Sánchez-Gilabert, A.; Ruiz, R.; Bejarano, Y.; Llinàs, P.; Gayá, A.; Bachiller, D. New bicistronic TALENs greatly improve genome editing. Curr. Protoc. Stem Cell Biol. 2020, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.Q.; Ding, Y.; Lu, Z.Y.; Hao, Y.Z.; Teng, Z.P.; Yan, S.R.; Li, D.S.; Zeng, Y. TALENs-mediated homozygous CCR5Δ32 mutations endow CD4+ U87 cells with resistance against HIV-1 infection. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, N.; Zhao, H. Seamless correction of the sickle cell disease mutation of the HBB gene in human induced pluripotent stem cells using TALENs. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2014, 111, 1048–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.M.; Kim, Y.; Shim, J.S.; Park, J.T.; Wang, R.-H.; Leach, S.D.; Liu, J.O.; Deng, C.; Ye, Z.; Jang, Y.-Y. Efficient drug screening and gene correction for treating liver disease using patient-specific stem cells. Hepatology 2013, 57, 2458–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Osborn, M.J.; Starker, C.G.; McElroy, A.N.; Webber, B.R.; Riddle, M.J.; Xia, L.; DeFeo, A.P.; Gabriel, R.; Schmidt, M.; Von Kalle, C.; et al. TALEN-based gene correction for epidermolysis bullosa. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shankar, S.; Prasad, D.; Sanawar, R.; Das, A.V.; Pillai, M.R. TALEN based HPV-E7 editing triggers necrotic cell death in cervical cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, Z.; Zou, Z.; Ding, F.; Li, L.; Wang, H.; Zhao, C.; Li, N.; Dai, Y. Efficient targeted integration into the bovine Rosa26 locus using TALENs. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, E.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, H.; Li, J.; Duan, R.; Hu, J. TALEN-mediated gene targeting for cystic fibrosis-gene therapy. Genes 2019, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, N.; Zhao, H. Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs): A highly efficient and versatile tool for genome editing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013, 110, 1811–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, R.; Berges, B.K.; Solis-Leal, A.; Igbinedion, O.; Strong, C.L.; Schiller, M.R. TALEN gene editing takes aim on HIV. Hum. Genet. 2016, 135, 1059–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Charlesworth, C.T.; Deshpande, P.S.; Dever, D.P.; Camarena, J.; Lemgart, V.T.; Cromer, M.K.; Vakulskas, C.A.; Collingwood, M.A.; Zhang, L.; Bode, N.M.; et al. Identification of preexisting adaptive immunity to Cas9 proteins in humans. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Makarova, K.S. Origins and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20180087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barman, A.; Deb, B.; Chakraborty, S. A glance at genome editing with CRISPR–Cas9 technology. Curr. Genet. 2019, 66, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawluk, A.; Davidson, A.R.; Maxwell, K.L. Anti-CRISPR: Discovery, mechanism and function. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 16, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Peng, N. Endogenous CRISPR-Cas system-based genome editing and antimicrobials: Review and prospects. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eid, A.; Alshareef, S.; Mahfouz, M.M. CRISPR base editors: Genome editing without double-stranded breaks. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 1955–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.H.; Miller, S.M.; Geurts, M.H.; Tang, W.; Chen, L.; Sun, N.; Zeina, C.M.; Gao, X.; Rees, H.A.; Lin, Z.; et al. Evolved Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nature 2018, 556, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satomura, A.; Nishioka, R.; Mori, H.; Sato, K.; Kuroda, K.; Ueda, M. Precise genome-wide base editing by the CRISPR Nickase system in yeast. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huang, C.-H.; Lee, K.-C.; Doudna, J.A. Applications of CRISPR-Cas enzymes in cancer therapeutics and detection. Trends Cancer 2018, 4, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakade, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Sakuma, T. Cas9, Cpf1 and C2c1/2/3―What’s next? Bioengineered 2017, 8, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.-S.; Li, Q.-C.; Yin, C.-Q.; Xue, W.; Song, C.-Q. Advances in CRISPR/Cas-based gene therapy in human genetic diseases. Theranostics 2020, 10, 4374–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Montoya, G. CRISPR-Cas12a: Functional overview and applications. Biomed. J. 2020, 43, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xiao, T.; Chen, C.-H.; Li, W.; Meyer, C.A.; Wu, Q.; Wu, D.; Cong, L.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.S.; et al. Sequence determinants of improved CRISPR SgRNA design. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, T.; Wei, J.J.; Sabatini, D.M.; Lander, E.S. Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science 2014, 343, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, N.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. WU-CRISPR: Characteristics of functional guide RNAs for the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.; Luk, K.; Wolfe, S.A.; Kim, J.-S. Evaluating and enhancing target specificity of gene-editing nucleases and deaminases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 191–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennox, K.A.; Behlke, M.A. Chemical modifications in RNA interference and CRISPR/Cas genome editing reagents. In RNA Interference and CRISPR Technologies; Sioud, M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2115, pp. 23–55. ISBN 978-1-07-160289-8. [Google Scholar]

- Doench, J.G.; Fusi, N.; Sullender, M.; Hegde, M.; Vaimberg, E.W.; Donovan, K.F.; Smith, I.; Tothova, Z.; Wilen, C.; Orchard, R.; et al. Optimized SgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strecker, J.; Jones, S.; Koopal, B.; Schmid-Burgk, J.; Zetsche, B.; Gao, L.; Makarova, K.S.; Koonin, E.V.; Zhang, F. Engineering of CRISPR-Cas12b for human genome editing. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, R.T.; Christie, K.A.; Whittaker, M.N.; Kleinstiver, B.P. Unconstrained genome targeting with near-PAMless engineered CRISPR-Cas9 variants. Science 2020, 368, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsur, M.B.; Shao, G.; Lv, Y.; Ahmad, S.; Wei, X.; Hu, P.; Tang, S. Base editing: The ever expanding clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) tool kit for precise genome editing in plants. Genes 2020, 11, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrian-Serrano, A.; Davies, B. CRISPR-Cas orthologues and variants: Optimizing the repertoire, specificity and delivery of genome engineering tools. Mamm. Genome 2017, 28, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khanzadi, M.N.; Khan, A.A. CRISPR/Cas9: Nature’s gift to prokaryotes and an auspicious tool in genome editing. J. Basic Microbiol. 2020, 60, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünewald, J.; Zhou, R.; Iyer, S.; Lareau, C.A.; Garcia, S.P.; Aryee, M.J.; Joung, J.K. CRISPR DNA base editors with reduced RNA off-target and self-editing activities. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Kao, J.-H.; Ching, C.; Liu, I.-J.; Wang, C.-C.; Tsai, C.-H.; Wu, F.-Y.; Liu, C.-J.; Chen, P.-J.; et al. Permanent inactivation of HBV genomes by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated non-cleavage base editing. Mol. Ther.-Nucleic Acids 2020, 20, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantor, A.; McClements, M.; MacLaren, R. CRISPR-Cas9 DNA base-editing and prime-editing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komor, A.C.; Kim, Y.B.; Packer, M.S.; Zuris, J.A.; Liu, D.R. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 2016, 533, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gaudelli, N.M.; Komor, A.C.; Rees, H.A.; Packer, M.S.; Badran, A.H.; Bryson, D.I.; Liu, D.R. Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 2017, 551, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Geen, H.; Bates, S.L.; Carter, S.S.; Nisson, K.A.; Halmai, J.; Fink, K.D.; Rhie, S.K.; Farnham, P.J.; Segal, D.J. Ezh2-DCas9 and KRAB-DCas9 enable engineering of epigenetic memory in a context-dependent manner. Epigenetics Chromatin 2019, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, M.; Gao, Y.; Dominguez, A.A.; Qi, L.S. CRISPR technologies for precise epigenome editing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, I.B.; D’Ippolito, A.M.; Vockley, C.M.; Thakore, P.I.; Crawford, G.E.; Reddy, T.E.; Gersbach, C.A. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.S.; Wu, H.; Ji, X.; Stelzer, Y.; Wu, X.; Czauderna, S.; Shu, J.; Dadon, D.; Young, R.A.; Jaenisch, R. Editing DNA methylation in the mammalian genome. Cell 2016, 167, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Broeders, M.; Herrero-Hernandez, P.; Ernst, M.P.T.; Van der Ploeg, A.T.; Pijnappel, W.W.M.P. Sharpening the molecular scissors: Advances in gene-editing technology. iScience 2020, 23, 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, D.B.T.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Franklin, B.; Kellner, M.J.; Joung, J.; Zhang, F. RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science 2017, 358, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, J.-J.; Orlova, N.; Oakes, B.L.; Ma, E.; Spinner, H.B.; Baney, K.L.M.; Chuck, J.; Tan, D.; Knott, G.J.; Harrington, L.B.; et al. CasX enzymes comprise a distinct family of RNA-guided genome editors. Nature 2019, 566, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Long, C.; Li, H.; McAnally, J.R.; Baskin, K.K.; Shelton, J.M.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. CRISPR-Cpf1 correction of muscular dystrophy mutations in human cardiomyocytes and mice. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1602814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- You, L.; Tong, R.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Xue, J.; Lu, Y. Advancements and obstacles of CRISPR-Cas9 technology in translational research. Mol. Ther.-Methods Clin. Dev. 2019, 13, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotterman, M.A.; Chalberg, T.W.; Schaffer, D.V. Viral vectors for gene therapy: Translational and clinical outlook. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 17, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, K.; Conboy, M.; Park, H.M.; Jiang, F.; Kim, H.J.; Dewitt, M.A.; Mackley, V.A.; Chang, K.; Rao, A.; Skinner, C.; et al. Nanoparticle delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein and donor DNA in vivo induces homology-directed DNA repair. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dever, D.P.; Bak, R.O.; Reinisch, A.; Camarena, J.; Washington, G.; Nicolas, C.E.; Pavel-Dinu, M.; Saxena, N.; Wilkens, A.B.; Mantri, S.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9 β-globin gene targeting in human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2016, 539, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Alphonse, M.; Liu, Q. Strategies for nonviral nanoparticle-based delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutics. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnology 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holkers, M.; Maggio, I.; Liu, J.; Janssen, J.M.; Miselli, F.; Mussolino, C.; Recchia, A.; Cathomen, T.; Gonçalves, M.A.F.V. Differential integrity of TALE nuclease genes following adenoviral and lentiviral vector gene transfer into human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, B.H. Recent advances in CRISPR/Cas9 delivery strategies. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Kriz, A.J.; Sharp, P.A. Target specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Quant. Biol. 2014, 2, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yin, H.; Song, C.-Q.; Suresh, S.; Wu, Q.; Walsh, S.; Rhym, L.H.; Mintzer, E.; Bolukbasi, M.F.; Zhu, L.J.; Kauffman, K.; et al. Structure-guided chemical modification of guide RNA enables potent non-viral in vivo genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.J. Adeno-associated virus and the development of adeno-associated virus vectors: A historical perspective. Mol. Ther. 2004, 10, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulcha, J.T.; Wang, Y.; Ma, H.; Tai, P.W.L.; Gao, G. Viral vector platforms within the gene therapy landscape. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, N.C.; Zimonjic, D.; DiPaolo, J.A. Viral integration, fragile sites, and proto-oncogenes in human neoplasia. Hum. Genet. 1990, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, M.J.; Kochanek, S. Adenovirus vectors: Biology, design, and production. In Adenoviruses: Model and Vectors in Virus-Host Interactions; Doerfler, W., Böhm, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 273, pp. 335–357. ISBN 978-3-642-05715-1. [Google Scholar]

- Muruve, D.A. The innate immune response to adenovirus vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004, 15, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.; Wang, M. Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells 2019, 8, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aoki, T.; Miyauchi, K.; Urano, E.; Ichikawa, R.; Komano, J. Protein transduction by pseudotyped lentivirus-like nanoparticles. Gene Ther. 2011, 18, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horii, T.; Arai, Y.; Yamazaki, M.; Morita, S.; Kimura, M.; Itoh, M.; Abe, Y.; Hatada, I. Validation of microinjection methods for generating knockout mice by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presente, A.F.; Dowdy, S. PTD/CPP peptide-mediated delivery of siRNAs. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 2943–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lino, C.A.; Harper, J.C.; Carney, J.P.; Timlin, J.A. Delivering CRISPR: A review of the challenges and approaches. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 1234–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xie, J.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Dong, S.; Teng, L.; Lee, R.J.; Yang, Z. Cell-penetrating peptides in diagnosis and treatment of human diseases: From preclinical research to clinical application. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, J.A.; Cullis, P.R.; Van der Meel, R. Lipid nanoparticles enabling gene therapies: From concepts to clinical utility. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2018, 28, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Pozo-Rodríguez, A.; Solinís, M.Á.; Rodríguez-Gascón, A. Applications of lipid nanoparticles in gene therapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 109, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiges, R.; Schuldiner, M.; Drukker, M.; Yanuka, O.; Itskovitz-Eldor, J.; Benvenisty, N. Establishment of human embryonic stem cell-transfected clones carrying a marker for undifferentiated cells. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Saha, K.; Kim, C.S.; Kim, S.T.; Landis, R.F.; Rotello, V.M. Gold nanoparticles for nucleic acid delivery. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bailly, A.-L.; Correard, F.; Popov, A.; Tselikov, G.; Chaspoul, F.; Appay, R.; Al-Kattan, A.; Kabashin, A.V.; Braguer, D.; Esteve, M.-A. In vivo evaluation of safety, biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of laser-synthesized gold nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, N.; Kim, H.K.; Lee, S.; Seo, J.H.; Choi, J.W.; Park, J.; Min, S.; Yoon, S.; Cho, S.-R.; Kim, H.H. Prediction of the sequence-specific cleavage activity of Cas9 variants. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Kwaku Dad, A.-B.; Beloor, J.; Gopalappa, R.; Lee, S.-K.; Kim, H. Gene disruption by cell-penetrating peptide-mediated delivery of Cas9 protein and guide RNA. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Cho, S.W.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.-S. Highly efficient RNA-guided genome editing in human cells via delivery of purified Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, X.; Seebeck, T.; Feng, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Davis, G.D.; Chen, F. Improving CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing efficiency by fusion with chromatin-modulating peptides. CRISPR J. 2019, 2, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzisheuskaya, A.; Shlyueva, D.; Müller, I.; Helin, K. Optimizing sgRNA position markedly improves the efficiency of CRISPR/DCas9-mediated transcriptional repression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Daer, R.; Hamna, F.; Barrett, C.M.; Haynes, K.A. Site-directed targeting of transcriptional activation-associated proteins to repressed chromatin restores CRISPR activity. APL Bioeng. 2020, 4, 016102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, Y.; Wu, X.; Guan, N.; Shao, J.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Ping, Y.; Li, D.; Ye, H. Engineering a far-red light–activated split-Cas9 system for remote-controlled genome editing of internal organs and tumors. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawluk, A.; Amrani, N.; Zhang, Y.; Garcia, B.; Hidalgo-Reyes, Y.; Lee, J.; Edraki, A.; Shah, M.; Sontheimer, E.J.; Maxwell, K.L.; et al. Naturally occurring off-switches for CRISPR-Cas9. Cell 2016, 167, 1829–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fu, Y.; Sander, J.D.; Reyon, D.; Cascio, V.M.; Joung, J.K. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cromwell, C.R.; Sung, K.; Park, J.; Krysler, A.R.; Jovel, J.; Kim, S.K.; Hubbard, B.P. Incorporation of bridged nucleic acids into CRISPR RNAs improves Cas9 endonuclease specificity. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilinger, J.P.; Thompson, D.B.; Liu, D.R. Fusion of catalytically inactive Cas9 to FokI nuclease improves the specificity of genome modification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyvekens, N.; Topkar, V.V.; Khayter, C.; Joung, J.K.; Tsai, S.Q. Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided FokI-dCas9 nucleases directed by truncated grnas for highly specific genome editing. Hum. Gene Ther. 2015, 26, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, S.W.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.; Kweon, J.; Kim, H.S.; Bae, S.; Kim, J.-S. Analysis of off-target effects of CRISPR/Cas-derived RNA-guided endonucleases and nickases. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frock, R.L.; Hu, J.; Meyers, R.M.; Ho, Y.-J.; Kii, E.; Alt, F.W. Genome-wide detection of DNA double-stranded breaks induced by engineered nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.V.; Sternberg, S.H.; Taylor, D.W.; Staahl, B.T.; Bardales, J.A.; Kornfeld, J.E.; Doudna, J.A. Rational design of a split-Cas9 enzyme complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2984–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zetsche, B.; Volz, S.E.; Zhang, F. A split-Cas9 architecture for inducible genome editing and transcription modulation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolukbasi, M.F.; Gupta, A.; Oikemus, S.; Derr, A.G.; Garber, M.; Brodsky, M.H.; Zhu, L.J.; Wolfe, S.A. DNA-binding-domain fusions enhance the targeting range and precision of Cas9. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Slaymaker, I.M.; Gao, L.; Zetsche, B.; Scott, D.A.; Yan, W.X.; Zhang, F. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science 2015, 351, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kleinstiver, B.P.; Pattanayak, V.; Prew, M.S.; Tsai, S.Q.; Nguyen, N.T.; Zheng, Z.; Joung, J.K. High-fidelity CRISPR–Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature 2016, 529, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Casini, A.; Olivieri, M.; Petris, G.; Montagna, C.; Reginato, G.; Maule, G.; Lorenzin, F.; Prandi, D.; Romanel, A.; Demichelis, F.; et al. A highly specific SpCas9 variant is identified by in vivo screening in yeast. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawley, A.B.; Henriksen, J.R.; Barrangou, R. CRISPRdisco: An automated pipeline for the discovery and analysis of CRISPR-Cas systems. CRISPR J. 2018, 1, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ihry, R.J.; Worringer, K.A.; Salick, M.R.; Frias, E.; Ho, D.; Theriault, K.; Kommineni, S.; Chen, J.; Sondey, M.; Ye, C.; et al. p53 inhibits CRISPR–Cas9 engineering in human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Application | Modification Rate/Gene of Interest | Delivery Ssystem and Modification Target | Meganuclease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) | 9% modification (indel formation) of COL7A1 in RDEB-K-SV40 cells | Integrase-deficient lentiviral vector (IDLV) | MN-i.1 lentiviral (I-CreI-derived MN isoschizomer targeting intron 2 of COL7A1) [21] |

| 7.5% modification (indel formation) of COL7A1 in RDEB-K (primary keratinocytes) | |||

| 2.2% modification (indel formation) of the COL7A1 gene in RDEB-F (primary fibroblasts) | |||

| Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) | Gene correction events of RAG1 in 5.3% of transfected cells | Plasmid in human 293H cells | RAG1 MN (single-chain I-CreI variant) [25] |

| Gene insertion for repairing RAG1 in up to 6% of transfected cells | RAG1 MN (single-chain I-CreI variant) [23] | ||

| Xeroderma pigmentosum group C (XPC) | High specificity in cleaving the XPC locus without apparent genotoxicity or evidence of off-target activity (specific rates not presented as percentages) | Lipofection in CHO-p10_XPC2 cells (efficiency) and human MRC5 cells (specificity) | Engineered variants of I-CreI (Ini3-Ini4 and Amel3-Amel4) [26] |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) | 13% and 30% expression of the corrected DMD gene (as compared to a positive control) using I-Scel and RAG1, respectively | Lipofection in 293FT cells | I-Scel and RAG1 [27] |

| Prevention of graft-versus-host disease | 1.6% disruption (indel formation) of the TCRα gene (with TCRα MN) 70.4% disruption (indel formation) of the TCRα gene (with TCRα MegaTAL) | Messenger RNA (mRNA) encoding the indicated constructs in human primary T cells | TCRα MN (I-OnuI variant engineered to knock-out TCRα) and TCRα megaTAL [19] |

| Strategy | Description | Strengths and Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Modular assembly [32] | Phage display-based. Seeks to identify individual ZFs with an established affinity for certain base triplets from an existing archive and link them together. | Reduces sequence specificity, binding affinity, and efficacy. Higher toxicity. |

| Oligomerised pool engineering (OPEN) [32] | Pre-established ZFNs, randomly assembled via PCR from a pool of ZFs, are screened against the target, and selected in a bacterial two-hybrid system. | Produces one of the highest specificities but requires significant time, labour and expertise. |

| Context-dependent assembly (CoDA) [32] | Targets a new sequence by exchanging ZFs between the already validated ZFNs that share a common middle ZF. Adequate for 3-ZF nucleases. | ZFNs produced with CoDA are less specific than those produced with OPEN, but the process is less technically demanding. |

| 2 + 2 [32] | 4-ZF nucleases are built by combining discrete 2-ZF subunits with known affinities, followed by optimisation. | Developed by Sangamo Biosciences and available commercially. |

| Sequential context-sensitive selection [42] | Uses transcription factor Zif268 as the starting framework and phage display for selection. Each ZF motif undergoes randomisation of six base-contacting residues and is progressively incorporated and optimised for target sequence and context before moving on to the next motif. | An early method for the retargeting of ZFNs. Due to its multiple selection rounds and emphasis on stepwise optimisation, it may be labour- and expertise-intensive. Outdated as compared to OPEN and CoDA. |

| Bipartite library [43] | Phage display-based. It uses two complementary libraries, each encoding a 3-ZF domain based on the transcription factor Zif268. One library features randomisations in base-contacting residues for ZF motifs 1 and 2, and the other for ZF motif 3. | Early strategy for the development of ZFNs. Outdated with regards to the more prevalent OPEN and CoDA strategies. |

| Application | Modification Rate/Gene of Interest | Delivery System | Modification Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Disruption of CCR5 with a frequency of 17% | Electroporation | CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) [51] |

| HIV-1 resistance | >50% disruption frequency of CCR5 | Adenoviral vector | GHOST-CCR5 cell line [52] |

| X-linked SCID | 6.6% homozygous cells with a modified IL2Rγ locus | Transfection and electroporation | K562 cell line [49] |

| X-linked SCID | 29% disruption frequency of IL2Rγ | IDLV | K562 cell line [31] |

| Sickle cell anemia | 37.9% modification rate of the β-globin gene | Electroporation | Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [53] |

| Leber congenital amaurosis | 85% indel frequency in the CEP290 gene | Messenger RNA (mRNA) delivery | K562 cells [46] |

| Application | Modification/Gene of Interest | Delivery System | Modification Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 infection (CCR5) | 50.4% targeted mutation frequency of CCR5 without selection; homologous recombination in 8.8% of the targeted cells (to CCR5Δ32). | Electroporation | CD4 + U87 cells [62] |

| Sickle cell disease (SCD) | Correction of mutation E6V in the HBB gene via HDR and a donor sequence; >60% of hiPSC colonies correctly targeted. | Electroporation | Patient-derived human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) [63] |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency | Correction of AAT Z mutation via HDR and a donor sequence; 25–33% biallelic targeting efficiency. | Electroporation | Patient-derived iPSCs with AAT deficiency [64] |

| Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) | Gene correction of COL7A1 via HDR and a donor sequence. Enables normal protein expression in a teratoma-based skin model in vivo. | Electroporation | Primary fibroblasts that were reprogrammed into iPSCs [65] |

| Comparison of specificity and cytotoxicity across human loci (CCR5, AAVS1, and IL2RG) | 6–17% allelic mutation frequency: CCR5 (7%), AAVS1 (6%), IL2RG (17%). | Electroporation | Primary human newborn foreskin fibroblasts (NuFFs) [41] |

| Editing of oncoprotein E7 from human papillomavirus (HPV) | ~10% editing efficiency of E7 accompanied by complete silencing. | Lipofection | SiHa cells [66] |

| Safe harbour-mediated knock-in in bovine cells | 70% knock-in efficiency (bRosa26 locus). | Electroporation | Bovine fetal fibroblasts (BFFs) [67] |

| Strategy | Form of Delivery | Strengths | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral delivery | Adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV) | DNA | No genome integration, low immunogenicity and high potential for in vivo applications with transient gene expression [116,117]. | Low capacity for cloning (<4.7 kb). The common strain of Cas9 from Streptococcus pyrogenes is a less feasible option due to its large size (~4.2 kb). Its efficiency in gene targeting is still low. |

| Lentiviral vectors (LV) | DNA | Higher capacity than AAV (<8 kb) with high efficiency across different cell types [108]. | Tumorigenesis concerns due to the activation of oncogenes by the random integration into the genome of the host cell [117,118]. | |

| Adenovirus (AV) | DNA | High transduction efficiency and broad tropism. No integration into host cells. Extensively studied for clinical trials [117]. | Laborious process for the production of AVs [119]. Pre-existing immunity to multiple AV serotypes [117]. Causes inflammation of tissues due to the innate immune response by its delivery [120]. | |

| Extracellular vesicles (EV) | Protein | No integration into the host genome as EVs do not contain any viral genome. Higher safety due to transient activity resulting in low off-target effects [113]. Intrinsic durability, tolerability, and potential for cell type-specific targeting [121]. | Quantification methods are limited. Significant need for standardisation of isolation and analytical procedures [121]. Protease cleavage in Cas9 may occur, which leads to its degradation [122]. | |

| Non-viral delivery | Microinjection | DNA, mRNA, or protein | Direct delivery into cells under controllable parameters. No capacity limitations for Cas9 delivery into the nucleus. | Laborious, low-throughput, requires a microscope for injection, and is not compatible with in vivo applications [123]. |

| Electroporation | Well-established methodology that has been proven efficient across a variety of cell types [110]. | Specialised equipment and potentially costly. Cell viability can be affected by the high electrical current. Not suitable for a variety of cell types due to sensitivity to stress. | ||

| Cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) | Protein | No random integration into the host genome. Its versatility enables a variety of cargoes to be delivered as complexes into cells [124]. | Variable efficiency requiring extensive optimisation [125]. Low stability and potential immunogenicity in vivo coupled with low intrinsic specificity [126]. | |

| Lipid-based nanoparticles (LNPs) | DNA, mRNA or Protein | High versatility, large capacity, minimised concerns of immunogenicity, extensive testing across clinical trials [127]. | Significant tailoring and optimisation of composition to maintain minimal toxicity and high efficiency for different routes of administration and cell types [127,128]. Low efficiency compared to viral delivery and electroporation [129]. | |

| Gold nanoparticles | Protein | Multiple controllable parameters, from size to surface functionalisation [130]. Nonimmunogenic responses with higher efficiency compared to LNPs [109]. | Potential for toxicity from residual contaminants (derived from conventional production) or stabilising agents [131]. Further research is required. |

| Rank | Cas Variant | Average Indel Frequency | Comparison with the Pprevious Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SpCas9 | 49% | - |

| 2 | Sniper-Cas9 | 46% | ≤ |

| 3 | eSpCas9(1.1) | 40% | < |

| 4 | SpCas9-HF1 | 34% | < |

| 5 | xCas9 | 32% | ≤ |

| 6 | HypaCas9 | 30% | ≈ |

| 7 | EvoCas9 | 15% | << |

| Rank | Cas Variant | Specificity 1–(Indel Frequencies at the Mismatched Target Sequences Divided by Those at the Perfectly Matched Targets) | Comparison with the Previous Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EvoCas9 | 0.89 | - |

| 2 | HypaCas9 | 0.67 | << |

| 3 | SpCas9-HF1 | 0.58 | ≤ |

| 4 | eSpCas9(1.1) | 0.50 | ≈ |

| 5 | xCas9 | 0.42 | < |

| 6 | Sniper-Cas9 | 0.36 | < |

| 7 | SpCas9 | 0.35 | < |

| Mitigation Strategy | Description | Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Truncated guide RNAs (gRNAs) | 17–18 (instead of 20) nucleotides complementary to the target site | Reduced off-target indels (up to 5000-fold) without sacrificing the efficiency of desired edits [140] |

| Chemical modification of gRNA | Incorporation of bridged nucleic acids into crRNA | Reduced off-target cleavage (up to 24,000-fold (site-dependent)) [141] |

| RNP delivery | RNA-guided engineered nuclease and gRNA are complexed for a direct delivery into cells | Compared to the plasmid delivery, reduced off-target indels (around 10-fold) and unwanted chromosomal rearrangements without sacrificing editing efficiency due to the rapid degradation (within 24 h) of the RNP in cells [134] |

| RNA-guided FokI–dCas9 nucleases (RFNs) | Fusion of dCas9 to the FokI nuclease (fCas9); requires functional dimers to cleave target DNA | On-target-to-off-target ratio (specificity) 140-fold higher than that of WT Cas9 [142] Further increase with truncated gRNA [143] |

| Paired Cas9 nickases | Double nicking with D10 (nuclease domain) | Production of indels at known off-target sites below the detection limit of 0.1%; increased differentiation of highly similar off-target sites (160- to 990-fold increase in on-target-to-off-target activity) [144]; minimises detectable off-target sites as assessed via HTGTS [145] |

| Split SpCas9 | Separates the two structural lobes comprising Cas9 (α-helical and nuclease) into distinct polypeptides to control assembly and activity [146]; Cas9 can also be split at suitable sites with the resulting fragments bound to rapamycin-binding domains (FRP, FKBP) to enable inducible dimerisation [147] | Lowers cleaving efficiency but promotes higher specificity [146] |

| Programmable DNA-binding domain–Cas chimera (Cas9–pDBD) | Programmable DNA-binding domain system—fusion of the ZF protein to SpCas9 increases the recognition site length | Up to 150-fold increase in the specificity ratio (on-target-to-off-target activity) [148] |

| Structure-based design | 1-eSpCas9(1.1) (enhanced Streptococcus pyrogenes Cas9): structure-guided design weakens the binding affinity to the nontarget DNA strand; this improves specificity by reducing binding stability at off-target sites whilst maintaining on-target activity [149] 2-SpCas-HF1 (high fidelity): reduced cleaving ability at off-target sites enabled by disrupting residues that form hydrogen bonds with the DNA backbone (thus limiting stability at mismatched sequences) [150] | |

| 3-EvoCas9: a Cas9 variant with four beneficial mutations resulting in a 79-fold specificity improvement compared to wild-type SpCas9 [151] 4-xCas9: broadened PAM recognition that supports an expanded sequence targeting capability with minimal off-target activity [77] | ||

| Anti-CRISPR | Ability to prevent the expression of Cas proteins, block cleavage activity and the CRISPR-Cas complex assembly, and inhibition of crRNA transcription and processing [74] | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González Castro, N.; Bjelic, J.; Malhotra, G.; Huang, C.; Alsaffar, S.H. Comparison of the Feasibility, Efficiency, and Safety of Genome Editing Technologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910355

González Castro N, Bjelic J, Malhotra G, Huang C, Alsaffar SH. Comparison of the Feasibility, Efficiency, and Safety of Genome Editing Technologies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(19):10355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910355

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález Castro, Nicolás, Jan Bjelic, Gunya Malhotra, Cong Huang, and Salman Hasan Alsaffar. 2021. "Comparison of the Feasibility, Efficiency, and Safety of Genome Editing Technologies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 19: 10355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910355

APA StyleGonzález Castro, N., Bjelic, J., Malhotra, G., Huang, C., & Alsaffar, S. H. (2021). Comparison of the Feasibility, Efficiency, and Safety of Genome Editing Technologies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(19), 10355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910355